William Bascom Wetherall saved numerous blue books from his college days at the University of Idaho. He also saved the following papers he submitted in various law courses. The texts shown here were created from optical character reader scans of image scans of the original reports. The OCR texts were vetted for scanning errors. [sic] and boxed comments are mine (William O. Wetherall).

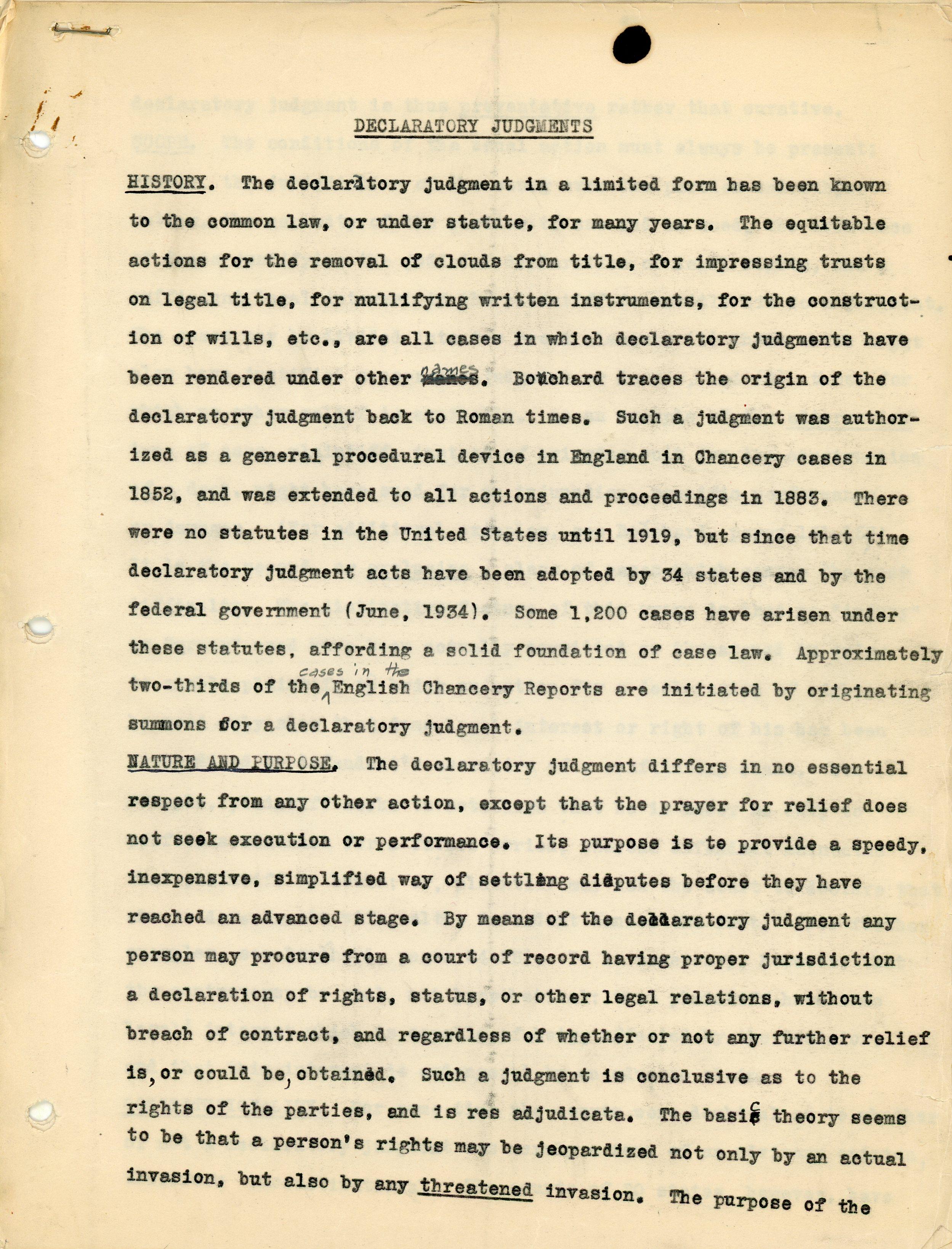

Declaratory Judgments (c1934-1935)This paper, undated, consists of 4 unnumbered double-spaced typescript pages. The title appears on the top of the 1st page. A few corrections have been made in pencil or black ink. The author's name appears at the end as "Bill Wetherall". The latest date in the paper is June 1934, and the paper is presumed to have been written in the fall or winter of that year, if not in 1935. The following transcription reflects all edits that the author himself made in the transcript, either by overstriking when typing the paper, or afterward by hand. The underscoring is as received in the typescript. The (parenthetic remarks) are as received but the [bracketed remarks] are mine. The comments and note on the primary inspiration and source of the paper, following the transcription, are also mine. DECLARATORY JUDGMENTS HISTORY. The declaratory Judgment in a limited form has been known to the common law, or under statute, for many years. The equitable actions for the removal of clouds from title, for impressing trusts on legal title, for nullifying written instruments, for the construction of wills, etc., are all cases in which declaratory judgments have been rendered under other names. Borchard traces the origin of the declaratory judgment back to Roman times. Such a judgment was authorized as a general procedural device in England in Chancery cases in 1852, and was extended to all actions and proceedings in 1883. There were no statutes in the United States until 1919, but since that time declaratory judgment acts have been adopted by 34 states and by the federal government (June, 1934). Some 1,200 cases have arisen under these statutes, affording a solid foundation of case law. Approximately two-thirds of the cases in the English Chancery Reports are initiated by originating summons for a declaratory judgment. NATURE AND PURPOSE. The declaratory judgment differs in no essential respect from any other action, except that the prayer for relief does not seek execution or performance. Its purpose is to provide a speedy, inexpensive, simplified way of settling disputes before they have reached an advanced stage. By means of the declaratory judgment any person may procure from a court of record having proper jurisdiction a declaration of rights, statue, or other legal relations, without breach of contract, and regardless of whether or not any further relief is, or could be, obtained. Such a judgment is conclusive as to the rights of the parties, and is res adjudicata. The basic theory seems to be that a person's rights may be jeopardized not only by an actual invasion, but also by any threatened invasion. The purpose of the declaratory judgment is thus preventative rather than curative. SCOPE. The conditions of the usual action must always be present; namely, the jurisdiction of the court over the parties and subject matter, the capacity of the parties to sue and be sued, the existence of facts justifying the judicial declaration of legal rights, and a sufficient legal interest in the plaintiff to entitle him to a judgment. The oases may be divided into two broad classes: (1) those which might also have justified a coercive judgment or decree, and (2) those for which no other relief is available. As an example of the alternative type of case, plaintiff, instead of bringing suit for the construction of a deed, might have sued for an injunction, specific performance, or damages. (For additional examples, see Borchard, pages 151-153). It is the second, or exclusive, class of cases which causes the most difficulty. The distinctive feature of this group is that no "injury" or "wrong" need have been actually committed or threatened in order to enable plaintiff to bring an action for a declaration of rights; he need only show that some legal interest or right of his has been jeopardized by defendant's assertion of a conflicting claim. For example, plaintiff seeks to establish that he is under no duty to perform a contract for a future period, whereas difendant [sic = defendant] maintains that plaintiff is bound; or, plaintiff may ask the court to declare that she is defendant's wife, altho [although] defendant denies the fact. (For further examples, see Bourhard [sic = Borchard], page 24-25). It is necessary, however, that the controversy be real, not hypothetical; that plaintiff have some legal interest which is capable of being affected by the decision; and that this interest is endangered by an adverse claim. CONSTITUTlONALITY. For some time the courts were doubtful as to whether or not a declaratory judgment was merely a form of an advisory opinion, therefore unconstitutional. The courts of 20 states, however, have decided unanimously in favor of constitutionality, emphasising the fact that a declaratory judgment is in no sense an advisory opinion. The federal act expressly provides for a declaratory adjudication only "in cases of actual controversy". SUPPLEMENTARY RELIEF. Further relief based on a declaratory judgment may be granted, whenever necessary or proper, upon application by petition to any court having jurisdiction to grant the relief. If the application is deemed sufficient, the court shall, on reasonable notice, require any adverse party to show cause why further relief should not be granted. (See Uniform Declaratory Judgments Act, sec. 8). On the other hand, the court may refuse to render a declaratory judgment or decree where it appears that such judgment or decree, if rendered, will rot terminate the uncertainty or controversy giving rise to the proceeding. (See Uniform Act, sec. 6). SUCCESS OF THE DECLARATORY JUDGMENT. As to the value of the declaratory judgment, Sunderland (Prof. of Law, Univ. of Mich.) says, "There is probably no parallel in American legal history to the sudden success of this measure for enlarging the usefullness of the courts." IDAHO LAW. Idaho adopted the Uniform Declaratory Judgments Act in 1933. (See Session Laws,, 1933, chap. 70). Idaho cases: First Nat. Bank of Boise v. Enking, 35P.(2d) 266. (Action to determine the interest rate to be paid by depositories of state and public funds.) State ex rel. Miller, Atty. Gen., v. State Board of Education, 52 P.(2d) 141. (Infirmary case). Distinguish between Uniform Declaratory Judgments Act and I.C.A. Title 7, chap. 10, entitled "Submitting Controversy Without Action". BIBLIOGRAPHY. Bourhard [sic = Borchard], Declaratory Judgments. Of special interest: Preface 16 Mich. L. Rev. 69 ---Bill Wetherall Comments"Declaratory judgments" was perhaps the hottest topic of the time, one that no law student could ignore. The paper is "sophomoric" in that it appears to have been written as part of a course assignment and was written in a very conventional report style. The typescript shows a number of corrections made by overstriking, and a number of other corrections have been made by hand, most in pencil, a few with a fountain pen. Of interest is my father's difficulty with the name of his primary source, Borchard. He initially spelled all four instances "Bouchard". When editing with a pencil, he corrected the first two instances to "Borchard" (changing the "u" to "r"), but miscorrected the second two instances to "Bourhard" (changing the "c" to "r"). Of interest also is his use of "altho" rather than "although" in an otherwise formal paper. Edwin BorchardEdwin Montefiore Borchard (1884-1951) was an international legal scholar at Yale Law School. He is best remembered for pioneering the adoption by the federal government and the states of so-called "declaratory judgments". The 1st edition of Borchard's Declaratory Judgments went to press as the Federal Declaratory Judgments Act was being signed into law by Franklin Delanor Roosevelt on 14 June 1934, which gave Federal Courts the power to render such judgements. See also Edwin Borchard, "The Federal Declaratory Judgements Act", 21 Virginia Law Review 35 (1934), Faculty Scholarship Series, 3645 (Yale Law School Legal Scholarship Repository). The following paragraph is extracted from a longer article about Edwin Borchard posted by Social Networks and Archival Context (SNAC),

|

Property Problems (1935)The paper consists of 28 unnumbered pages including title page. The title appears only on the title page, and the body of the text is mostly citations, in single-spaced typescript, from statutes and rulings. There are no end notes. A few bibliographic particulars have been noted in blue ink. PROPERTY PROBLEMS I.C.A. 54-201 Limitation of Future Estates.-- A future estate may be limited by the act of the party to commence in possession of a future day, either without the intervention of a precedent estate, or on the termination by lapse of time or otherwise, of a precedent estate created at the same time. |

The Determination of the Admissibility of Evidence (1936)The paper consists of 1 title page and 11 numbered pages of double-spaced typescript. The page numbers, and the end-note numbers in the body of the paper, are written in red ink. Some few corrections have been made in blue ink. Paper on --Bill Wetherall THE DETERMINATION OF THE ADMISSIBILITY OF EVIDENCE |

Presumptions and the Burden of Proof (1936)The paper consists of 1 title page and 22 numbered pages of double-spaced typescript. The page numbers, and the end-note numbers in the body of the paper, are written in red ink. Some corrections have been made in pencil, and there are a few notations, mostly case numbers, in blue ink. Paper on May 31, 1936 PRESUMPTIONS AND THE BURDEN OF PROOF I. BURDEN OF PROOF II. PRESUMPTIONS III. IDAHO LAW |

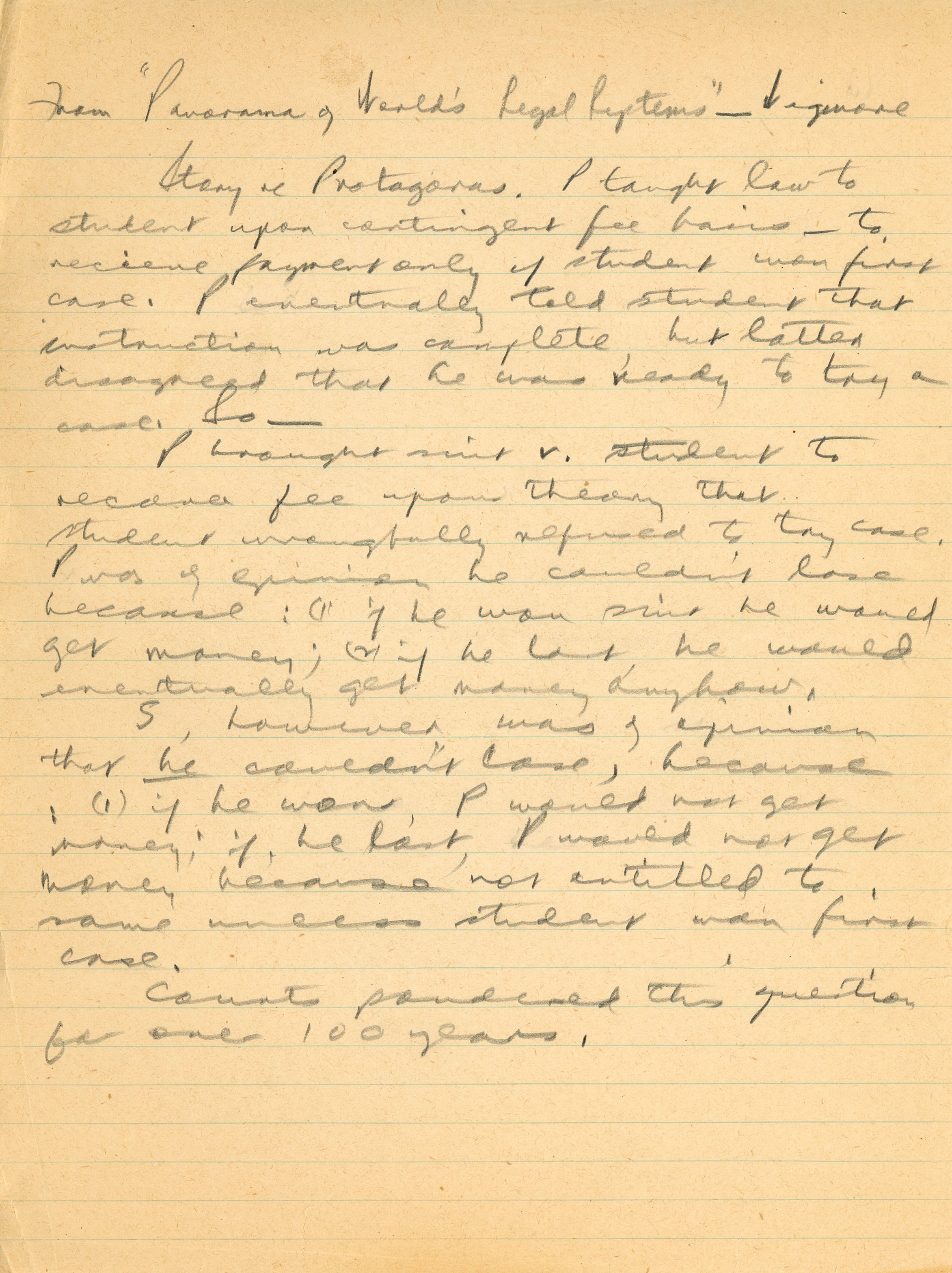

Story of Protagoras (circa 1935)From Wigmore's "Panorama of World's Legal Systems"One of the more interesting items among my father's papers was a single sheet of ruled tablet paper on which, in pencil, he had paraphrased a well-known conundrum in the history of law and logic. I imagine him and his classmates wrestling with the possible arguments into the wee hours of the night, possibly fueled by beer. From "Panorama of World's Legal Systems" -- Wigmore Story of Protagoras. P taught law to student upon contingency basis -- to receive payment only if student won first case. P eventually told student that instruction was complete but latter disagreed that he was ready to take a case. So -- P brought suit v. student to recover fee upon theory that student wrongfully refused to try case. P was of opinion that he couldn't lose because: (1) if he won case he would get money; (2) if he lost he would eventually get money anyhow. S, however, was of opinion that he couldn't lose, because: (1) if he won, P would not get money because not entitled to same unless student won first case. Courts pondered this question for over 100 years. SourceMy father probably read the story of Protagoras in the following edition of Wigmore's then very well-known book.

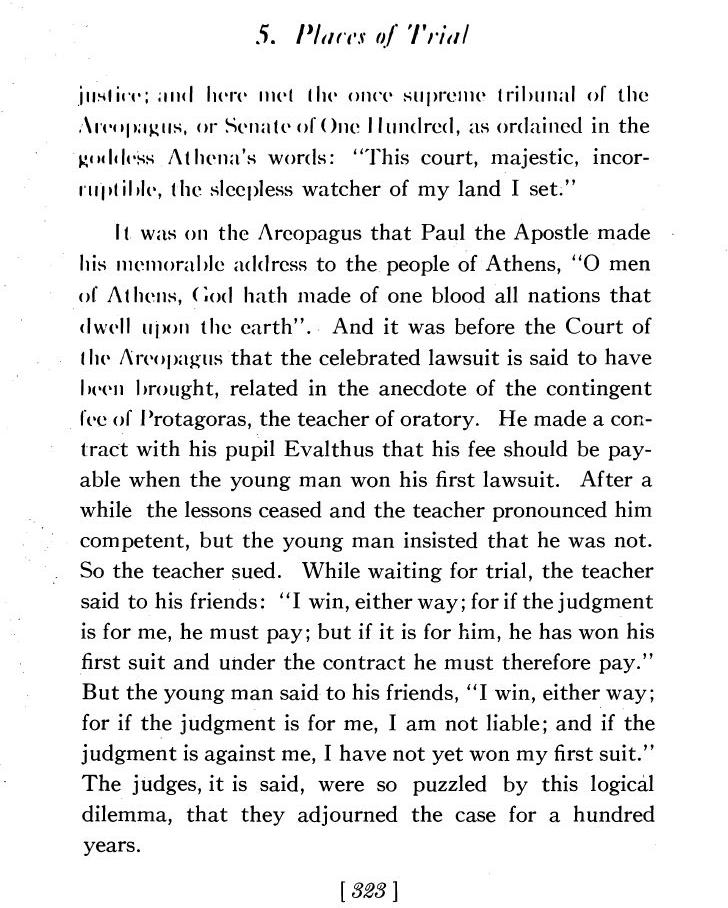

John Henry Wigmore The above edition was reissued in 1936 by Washington Law Book Company in Washington, DC. The book remained very popular, and remained in print for many years. It is, in fact, a very interesting work. Volume 2 begins with a look at law in Japan from the earliest times. The story as told by Wigmore (see image to right) reads as follows (Wigmore 1928, Volume 1, page 323). It was on the Areopagus that Paul the Apostle made his memorable address to the people of Athens, "O men of Athens, God has made of one blood all nations that dwell upon the earth". And it was before the Court of the Areopagus that the celebrated lawsuit is said to have been brought, related in the anecdote of the contingent fee of Protagoras, the teacher of oratory. He made a contract with his pupil Evalthus that his fee should be payable when the young man won his first lawsuit. After a while the lessons ceased and the teacher pronounced him competent, but the young man insisted that he was not. So the teacher sued. While waiting for trial, the teacher said to his friends: "I win, either way; for if the judgment is for me, he must pay; but if it is for him, he has won his first suit and under the contract he must therefore pay." But the young man said to his friends, "I win, either way; for if the judgment is for me, I am not liable; and if the judgment is against me, I have not yet won my first suit." The judges, it is said, were so puzzled by this logical dilemma, that they adjourned the case for a hundred years. Paul the Apostle's sermon before the people of Athens is related in Acts 17:16-34 in the New Testament of the Bible. The remark about all nations being made of "one blood" is from Acts 17:26. Wetherall v. WigmoreWigmore related the story better than my father. My father, in paraphrasing Wigmore, resorted to legalese that Wigmore would probably have viewed as pretentious when telling a story, though expected of a student. A good legalist with a sense of style will eschew legalese when not required, knowing that legalese, unless intended as humor, is the best way to kill a story. As a law student, however, my father was probably heady with the language of law, and was bent on using it every opportunity he got. Perhaps he even proposed to my mother in legalese. I recall doing the same thing when going to college. Some of my student papers reek of fashionable "scholarese" -- a habit I struggled to break when relearning to write as a journalist and novelist. Wikipedia articleThere are many versions of this story. Wikipedia presents another in the following article, titled Paradox of the Court, parts of which I have slightly reformated.

|

|||||