Ogawa Enson (editor) The editor, Ogawa Enson (Tachiro, 1877-?), was a novelist and playwright. His younger brother was the painter Ogawa Sen'yo (Tasaburo, 1882-1971). It is not clear what role Ogawa played in the compilation of this volume, which was published and printed under the direction of the "Color picture division" of the "Customs, picture scrolls, and drawings publishing association", a group which reproduced compact editions of several late Edo and early Meiji woodblock print sets during the Taisho period. This volume is the third in a series of six "nishikie bunko" (color woodblock print pocket books), according to an advertisement on the last page.

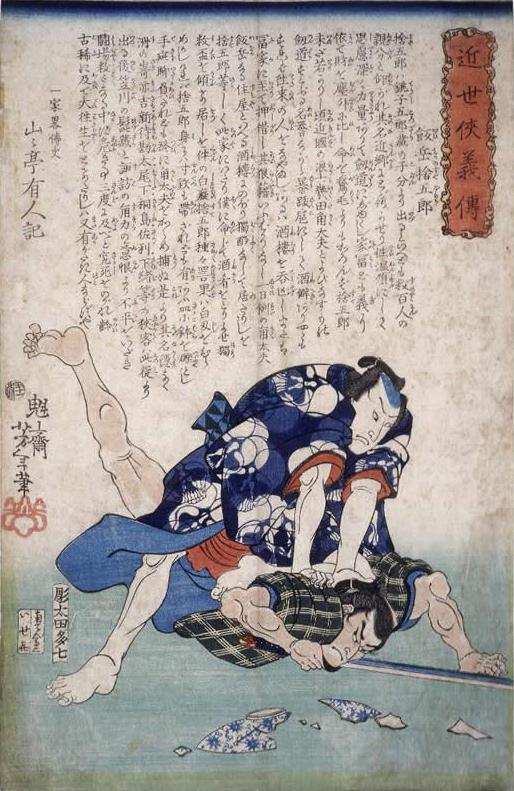

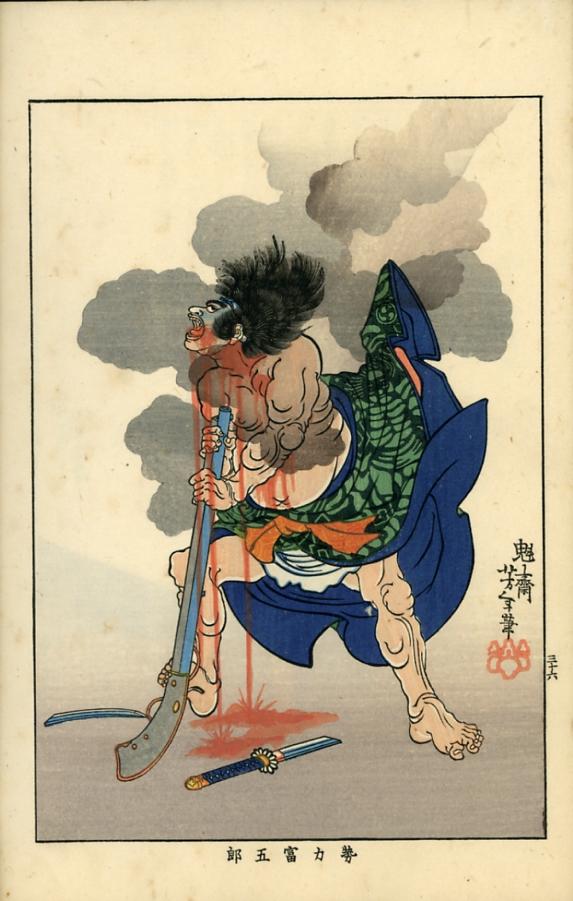

Kinsei kyogi den is usually dubbed "Biographies of Modern Men" in English. The translation is short, simple, and misleading. The men were not "modern", the stories are not "biographies", and the most important word -- chivalry -- has been lost. Kinsei (近世) means "recent times" or "recent world/life" and may also imply "contemporary" but with a "near past" more than "now" focus. Kyogi (侠義) means "chivalry" (today more commonly "gikyo"), especially in codes of honor among gamblers and others who make their livings on the fringes of the law. Den (傳 / 伝) is a "received story" or "episode" from real life or legend and is best not translated "life of" or "biography of" when not following someone's name. The volume consists of 38 large (nearly B4, oban) sheets that have been printed on old side and folded in half to make two small (nearly B5, chuban) pages. The folded sheets, consisting of 76 pages, are bound on the right between soft covers with string in the older manner of bookmaking in Japan. The front cover has a title slip with characters reading Kinsei kyogi den (Zen) The original prints were printed on oban (roughly B4) sheets and feature text integrated with foreground and background images. The reproductions in this book are about half the size of the originals but feature only the foreground image, without the background image or text. The reproduced images are very high quality copies of the originals. They show that the skills of Taisho woodblock carvers and printers are on a par with those of their late Edo antecedents. While page size is roughly half the original sheet size, the reproduced images are about three-quarters the size of the original foreground images. Each picture page is faced by a story page. The story text is not, however, a transcription of the original text by Sansantei Arindo. In fact, his name does not appear in the book -- as though he and his stories never existed. The name of the original carver and publisher are not mentioned either -- as though only Yoshitoshi had created and published the original prints. The compilers of this volume clearly had more in mind than merely reproducing Yoshitoshi's and Sansantei's work. The names of some of the characters who figure in the episodes also differ. Some of the stories describing their feats bear little resemblance to Sansantei's stories. Even the images, though generally very faithful, may have undergone a certain amount of editing to reflect what the editors regard as differences in taste between late Edo and Taisho. In a word, despite their late Edo roots, the prints and stories in this book are Taisho reincarnations -- of, by, and for denizens of the Taisho period. And as such they are a Taisho, rather than truly contemporary, mirror of the 1860s when the original prints were published, and of the 1840s whose events the prints narrate through their pictures and texts. |

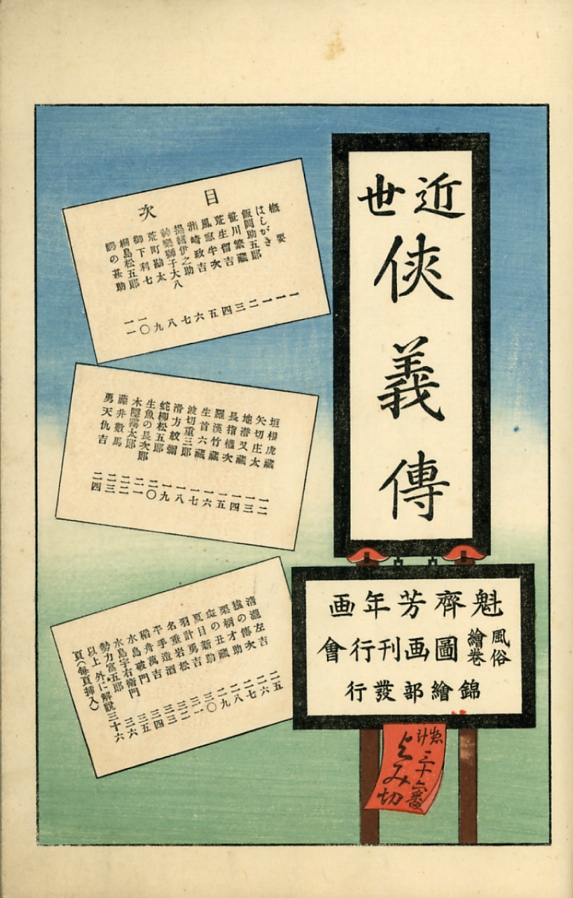

ContentsThe contents of the 76 pages between the covers of this book of reproductions are as follows. 1. Title page, contents, publishing credits A single wood-block-printed page shows the title and publishing credits. Three cartouches list the 36 persons (all men, no women) whose chivalrous acts are shown and narrated in the pictures and stories. The picture and story pages for each person face each other, and both pages are given the same number, 1 through 36. 2. Theme of prints A single-page article entitled Kinsei kyogi den gaiyo [Overview of Stories of chivalry in recent times] introduces Sukegoro and Shigezo, the two rivals who were at the center of a turf war that caught the attention of the Kanto area centering on Edo. The first sentence translates as follows.

3. Settings of prints A single-page article entitled Kinsei kyogi den hashigaki [Stories of chivalry in recent times preface], attributed to the editors and dated the 9th month of the 6th year of Taisho (September 1917), introduces the prints in relation to the times in which they were published, meaning both late Edo (original prints) and Taisho (reproductions). The last two paragraphs translate as follows.

ZatoichiThe rivalry between Sukegoro and Shigezo is the stage for a long list of Zatoichi movies, beginning with Zatoichi monogatari [The Tales of Zatoichi, aka Zatoichi Story, aka Zatoichi: The Life and Opinions of Masseur Ichi] and Zoku Zatoichi monogatari [The Tale of Zatoichi Continues]. Both of these films, the first directed by Misumi Kenji, the sequel by Mori Kazuo, were released by Daiei in 1962. Zatoichi is played in these and subsequent edisodes in the Zatoichi film series by Katsu Shintaro. Takeshi Kitano plays Zatoichi in his own 2003 production. The Zatoichi character is supposedly based on a man in Sukegoro's camp who was blind but had uncanny intuitions when it came to gambling. Whether the real-life Zatoichi got the girl in the end is not known. Tenpo Suiko denZatoichi films are only the most recent "spinoffs" of the Tonegawa turf war, which is better known as Tenpo Suiko den (天保水滸伝). Tenpo refers to the period (1830-1844) at the end of which the Tonegawa saga unfolded. Suiko den is the Sino-Japanese reading of characters which, in present-day Chinese, read Shuihu zhuan, the title of a Ming dynasty novel by Shi Naian (1296?-1370?) and/or Luo Guanzhong (c1330-1400), featuring stories of heroic outlaws who battled against corrupt officials during the Song dynasty. "Suiko den" is therefore a metaphor for stories about underdogs who fight for justice. Any story with a title of the formula "XYZ Suiko den" will be a romantic adventure about people who rebel to improve the lot of the poor in their struggle against authorities who get rich through their abuse of the common people. "Shuihu zhuan / Suiko den" is often translated "The Water Margin" or "Outlaws of the Marsh" in English, reflecting the setting of the stories in "suiko" or the damp fringes of a body of water, such as the edges or banks of a river or lake, or the lims of a marsh. Shuihu zhuan is about a group of 108 bandits, led by Song Jiang (宋江), who rebelled against injustice from their base in Liangshan swamp (梁山泊) in the Liangshan mountains in 1119-1121. Though fictionalized, its characters and their deeds are based on historical figures and events. "Suiko den" this and "Suiko den" that have been enormously popular in the fableizing of popular heroes in Japan. Numerous movies, comics, animated films, and computer games have been spun from the threads of Chinese and Japanese "Suiko den" stories. KKD as news in reviewYoshitoshi's Kinsei kyogi den was among the earliest attempts to convey the stories of the Tonegawa war in pictures accompanied by text. Yoshitoshi designed the series barely two decades after the confrontations between Sukegoro and Shigezo (1844-1849). Sukegoro, who died in 1859, had been dead only six years when Yoshitoshi drew "Iioka no Sutegoro" in 1865. In some sense, then, Kinsei kyogi den was a visual recap of recent news with running commentary by Sansantei Arindo. The Meiji period saw the publication of longer, better researched rehashings of the Tonegawa war, such as Tenpo Suiko den, a 254-page account published in 1888 by Bunshodo. Edited by Tagaki Ichin [tentative reading, dates unknown] and illustrated by Ogata Gekko (1859-1920), this book reflects presumably more accurate versons of names that, in Yoshitoshi's time, had become corrupted by dialect and errors in oral transmission. Tanaka KakueiTenpo Suiko den is also the title of a naniwabushi (浪花節), or rokyoku (浪曲), a story usually narrated by a solo reciter to the accompaniment of a single shamisen. Naniwabushi seem to have originated as a form of popular entertainment in Osaka during the middle of the Tokugawa period and then spread to Edo. Since naniwabushi stories are typically sentimental, "naniwabushi" has become a metaphor for a tear-jerker about morality and self-sacrifice. Some Naniwabushi are full of martial bravado, and others are bawdy. And so "naniwabushi" also connotes militaristic, vulgar, rural, or otherwise tasteless, low-class, and out-of-date. Years before becoming prime minister, Tanaka Kakuei (1918-1993) was dubbed the "Naniwabushi minister". In 1957, Tanaka was appointed the Minister of Posts and Telecommunications in Kishi Nobusuke's first cabinet. Already notorious, and influential beyond his age, the young politician from Niigata got a lot of attention on the airwaves, then still mainly radio. NHK, aka as Japan Broadcasting Corporation, invited Tanaka to appear on a radio interview. In the course of the interview, Tanaka said he liked naniwabushi and was pressed to recite an example. Tanaka launched into Tenpo Suiko den, and soon the whole nation was hearing Kishi's youngest cabinet minister eulogize a bunch of gamblers who tossed around gold coins and killed each other. Unable to stop him, NHK pulled the plug -- and even the Diet debated the propriety of Tanaka's impromptu performance. The negative attention from elites who looked down on him only enhanced his image and status as a new folk hero. [I am particularly indebeted to Steven Hunziker and Ikuro Kamimura, Kakuei Tanaka: A Political Biography of Modern Japan, Chapter 3 (Internet), for the story of Tanaka's encounter with NHK.] Print informationSeries name: Kinsei kyogi den Principal sourcesPrimary: Publication under review in Yosha Bunko, and Japanese Internet sources. Secondary: Segi 1985:32 plate 1; van den Ing and Schaap 1992:37 plate 13.11, 102. |