Tonichi and Iwakura Embassy

Inaugural issue report on snowy Sierras and polygamous Salt Lake City

By William Wetherall

First posted 3 February 2008

Last updated 10 June 2008

Letter from America

Salt Lake City story

Iwakura Embassy

Iwakura mission chronology

•

Kume Kunitake's account

•

Moriya Kan'ya's "western kabuki"

•

Sources

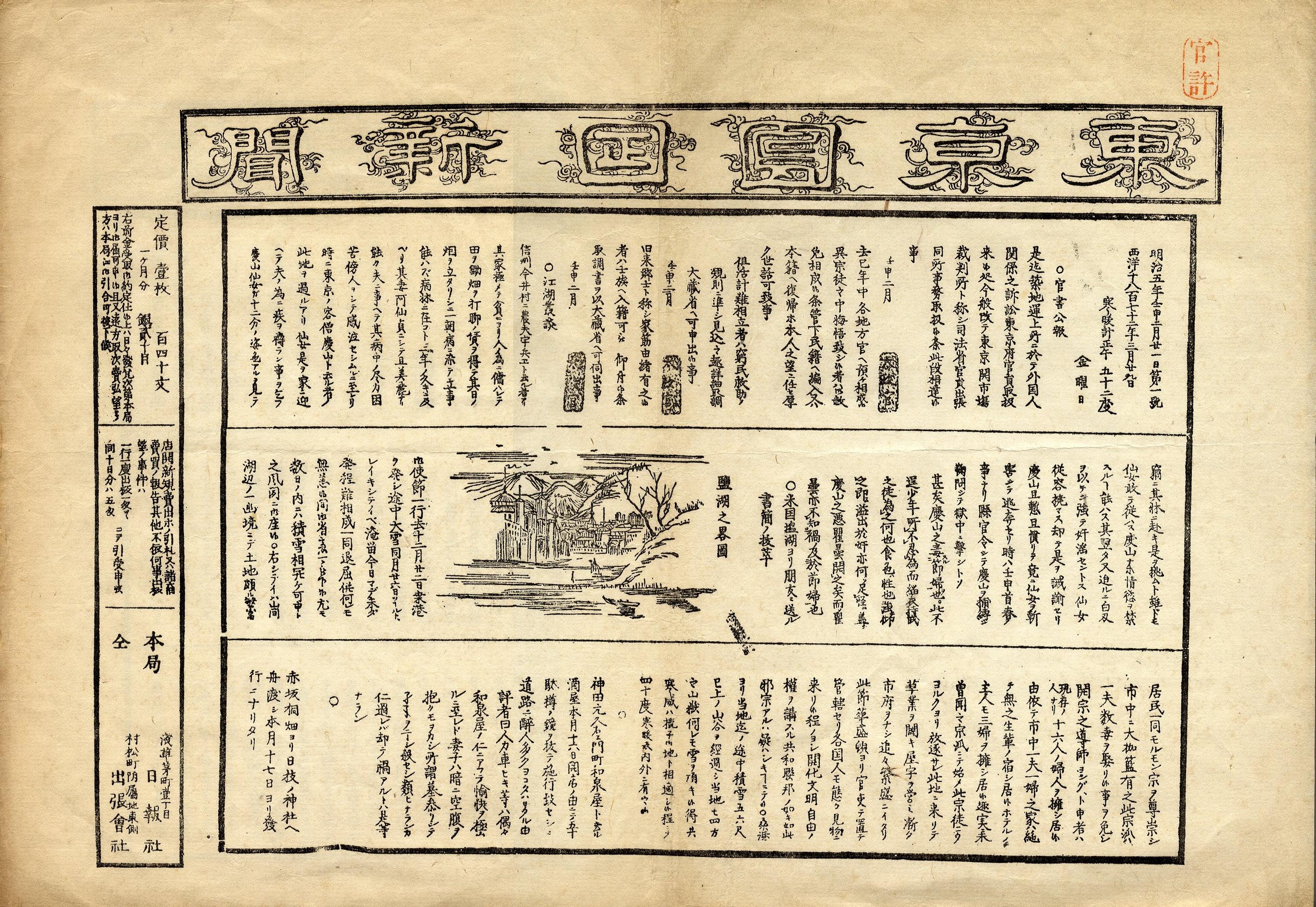

Letter from AmericaThe first issue of the Tōkyō nichinichi shinbun (東亰日日新聞 "Tokyo daily news"), shown to the right, was printed using hand-carved woodblocks. The next several issues, similarily designed and sized, were printed using moveable metal type. The paper is the forerunner of today's Mainichi shinbun, which originated in Ōsaka. The paper was commonly called just "Tōnichi" (東日) in Japanese. Here I am calling it "Tonichi". The scan to the right is of a very high quality facsimile printed in 1921. Smaller scans of (apparently) original copies can be found in Mainichi 1962: frontispiece; Mainichi 1972a: frontispiece, 2-3; Mainichi 1972b: frontispiece; Machida 1986: 35; Kinoshita and Yoshimi 1999: 148; and Newspark 2000: 9, et cetera). Issue 1 storiesThe most sensational story in Tonichi's inagural issue was a true-crime report about the "wicked priest Keizan" who robs and kills the "virtuous woman Sen". Sen gave Keizan lodging, thinking he would say sutras for her sick husband, then defended her honor when he attacked her. The story was retold on a woodblock print published around October 1874). See Priest kills woman (TSN-001) on the News Nishikie website for scans and other details. The centerpiece of the single-page inaugural edition of Tokyo nichinichi shinbun -- shown to the right -- is a picture captioned "Sketch of Azure Lake" (Aiumi [Ranko] no ryakuzu 藍湖之畧圖). The drawing illustrates a story called "Extract of letter: Sent by friend from Salt Lake in America" (Beikoku Enko yori hōyū ni okuru shokan no bassui 米国塩湖ヨリ朋友ニ送ル書簡ノ抜粋). The graph for "azure" (藍) in the caption of the sketch may be an error for the "salt" (塩) in the story title. If an error, it could have been made by the writer of the letter, the scribe who transcribed the letter to the sheet of thin paper used to carve the block, or the carver who had to engrave the graphs from the back of the paper hence as laterally transposed (left-right mirror) images. But WYSIWYG (what you see is what you get). No "Errata" notices were published. Readers were free to imagine that the "salt lake" appeared to be an "azure lake". And who is to say that the writer didn't intend this image? In the body of the story (see below), "Salt Lake City" is transcribed "Sooruto reiki shitii" (ソールトレイキシテイ). The names of the sender and recipient -- if other than the writer -- are not disclosed. And the article is not signed -- but we can surmise that the writer is Jōno Denpei (條野伝平 1832-1902), and that he received the letter from a friend who probably knew that Jōno, Nishida, Yoshiiku, and Hirooka were launching the paper (see Tōnichi's earliest issues for details). The identities of Tonichi's founders, and the circumstances under which they produced its earliest issues, suggest that Jōno Denpei wrote the article, based on a letter he had recieved from his friend Fukuchi Fukuchi Gen'ichirō (福地源一郎 1841-1906). Fukuchi was a member of the so-called Iwakura Embassy (Iwakura shisetsudan 岩倉使節団), a mission or delgation headed by Iwakura Tomomi (岩倉具視 1825-1883)., a member of the Iwakura Embassy that was then traveling across the United States, became Tonichi's chief editor in 1874. . Jōno and Fukuchi had collaborated in 1968 to publish the KōKo shinbun (江湖新聞 "World news") Koko shinbunwho with Jōno's help had published Koko shinbun in 1868. Fukuchi joined Tonichi and became its chief editor in 1874. At the time, though, he was a member of the Iwakura Embassy The dates and events in the article point directly to a delegate with the Iwakura Embassy, which was barely two months into its nearly 2-year world journey from December 1871 to September 1873. Salt Lake City storyThe story begins with the the departure from San Francisco (桑港) on the 22nd day of the 12th month of the previous year [Meiji 4-12-22 == 20 January 1872] and the arrival in Salt Lake City (ソールトレイキシテイ) on the 26th of the same month [24 January 1872], after encountering heavy snow enroute. The writer observes that a certain religious man named Young (Yongu ヨング) has 16 wives, that no family in the city consists of only one husband and one wife, that the propritor of the hotel where they stayed has three wives. The letter returns to the snow encountered enroute, and describes the snowpack and cold in the mountains, which appear to be the Sierras. Not yet fully three years had passed since 10 May 1869, when Chinese track gangs met their Irish counterparts at Promontory Summit near Salt Lake City, to complete the Transcontinental Railway between Sacramento and Omaha. The writer would have boarded the train at Oakland after crossing San Francisco bay by ferry. After passing through Sacramento and Rosesville, the train began its slow climb through several towns in the foothills of the Sierras, then traversed Emigrant Gap and crossed the summit at Donner Pass, which had slowed and defeated many westward-bound wagon trains in winter, continued east through Truckee, and skirted the northern shore of Lake Tahoe as it passed from California into Nevada, before crossing the desert to a shrunken Utah Territory -- still a quarter century from statehood -- all that was left of what Mormons had hoped would be a huge city called Deseret. The territory was still a stage for skirmishes between invading settlers and indigenous Indian tribes. The only Orientals in the area were Chinese laborers who had stayed to work on track gangs. The following transcription reproduces the kana orthography in the received text but shows present-day kanji. Note that "sōrō" (候) is systematically abbreviated in the text. Note also that the only voicing marked in the text is in the "gu" (グ) of the transcription of Brigham Young's name "Young" (Yongu ヨング). Native speakers of Japanese reading ヨング as though it might be a Yamato word would prounce ヨン "yoŋ" and グ either soft "ŋu" (possibly reducing "u" to the point that the mora sound close to just "ŋ), or hard "gu" (in which "u" is not reduced). Not knowing the English spelling of the name "Young", much less how a native speaker of English would probably prounce the name, some native speakers of Japanese might intentionally read ヨング as "yoŋ-gu". Such variation only shows that, just as no word is ever self-defining, no script is ever self-pronouncing. All "readable" script will be "read" in accordance with whatever reading rules the reader has internalized for the script. Hence most native speakers of English unfamiliar with Japanese morae will read alphabetis "Toyota" something like "Toy-OH-tuh". And note, finally, that there is no puncutation -- except what appears to be a comma before the "Yongu" (ヨング) and the "to" (ト) before "mousu mono" (申者) -- i.e., "Yongu, to mousu mono" -- which anticipated the options available to later (and present-day) writers. I have highlighted the circles used to separate blocks of text in red bold, hence 〇, simply to make them more distinct. I have also marked the phrase 現存ノ人ナリ in red to point out that it is an in-line comment, here to the effect that Young is a person who now exists. Today such comments would be bracketed in parentheses. The convention at the time was to insert such commentary in two lines. This is very possibly an editorial clarification.

〇 米国塩湖ヨリ朋友ニ送ル書簡ノ抜粋 This story has gotten some play in Japanese academia and media but is not that well known. http://zenmz.exblog.jp/1330511/ Kibino Zenzō (吉備野禅三 b1930) of Okayama prefecture, in the 8 October 2005 edition of his personal blog zenmz, transcribed the story in the course of talking about Japan's first newspaper (5154 日本最初の新聞について), referring to Tokyo Nichinichi Shinbun, which began publishing in 1872. Hibino touched upon the inagural edition in the preceding blog (5153) as well. I myself had collected a facscimile of the 1st edition, and also original copies of several of the immediately following editions. I had also extensively studied some of the founders of the paper, who in 1875 began producing a run of nishikie stories based on incidents reported in the "Tonichi" (Tōnichi 東日) as the paper came to be called. My studies of these subjects are the subject of my www.nishikie.com webisite. of the they 日本最初の新聞について (5154). http://garyo.or.tv/bbs/wforum.cgi?mode=past&page=10&word=%8D%DA%82%C1&view=10&cond=&pastlog=0005&wsearch=1&hlight=&smethod= タイトル : 福地源一郎の見たソルトレ-ク 記事No : 2782 [関連記事] 投稿日 : 2005/02/12(Sat) 09:16:04 投稿者 : るう@世話人 URL : http://garyo.or.tv/mormon.htm るう@世話人です 木戸孝允は所謂岩倉使節団の一員として、アメリカからヨ-ロッパ へと視察を続けるわけですが、その中には日本の新聞界の創始者と も言うべき福地源一郎(桜痴)がいました。 福地はソルトレ-クから記事を発信しており、その記事が毎日新聞 の創刊第一号(当時:東京日日新聞)に載ったということです。 毎日新聞の創刊第一面「モルモン教関連ニュ-ス」だったわけです。 ソルトレ-ク五輪がまじかの2002年の2月8日の毎日新聞の「余録」 にはこの話題が取り上げられています。 *-*-*-*-*-*-* 毎日新聞の創刊第1号を開くと… 毎日新聞の創刊第1号を開くと、中央にソルトレ-クシティ-の風景が載っ ている。写真ではなく木版。文字ばかりの紙面のなかで唯一のイラストがこれ ▲1872(明治5)年2月21日に発行された東京日日新聞(毎日新聞の前 身)の第1号は、上段の題字と紙面左側の定価・広告料などの欄がセピア色、 本文は黒の2色刷り。紙面全体に淡いセピアがかかっている。イラストの題は ソルトレ-クを直訳して「塩湖の略図」▲手前に湖が広がり、かなたには山々 がそびえている。大きい伽藍(がらん)はモルモン教の寺院に違いない。空を 飛んでいるのはユタ州の州鳥、カモメか。塩湖風景にそえて、岩倉具視、木戸 孝允、大久保利通、伊藤博文ら総勢約50人の岩倉使節団が豪雪のために足止 めを食った記事が載っている▲使節団は71年12月22日、サンフランシス コを出発し、途中大雪のため26日、ソルトレ-クシティ-に滞在、いまだに 出発できずにいる。同市は山間湖辺の幽境で、すこぶる繁盛、住民一同モルモ ン教を尊崇し、市中に大伽藍これあり、と記事は続く▲ただの雑報でなく「米 国塩湖より朋友に送る書簡の抜粋」と手紙の形をとっている。こんなしゃれた ことをする者はだれだろうと「『毎日』の3世紀」(毎日新聞社)を見たら、 筆者は使節団に随行した福地源一郎だった。オランダ語、英語、フランス語に 通じ、東京日日新聞社長になった人物だ▲「特命全権大使米欧回覧実記」(岩 波文庫)にも塩湖で立ち往生した話が出てくる。明治の人たちは塩湖をよく知っ ていた。8日に開幕するソルトレ-ク冬季五輪がはじめてという気がしないの はそのせいか。とりわけ本紙はうれしい。創刊130年と五輪が2月のソルト レ-クで手を結ぶのだから。Iwakura EmbassyThe dates and settings of the Salt Lake City story are significant clues regarding who wrote the letter to whom. The day the mission left Yokohama, Japan had 306 polities -- 1 commission (使 shi), 3 urban prefectures (府 fu), and 302 prefectures (県 ken). The following day, Japan's polity map began to undergo major surgery. By the time the mission had completed half its crossing, Japan had only 76 polities -- The Development Mission (開拓使 Kaitakushi) in Hokkaido, the urban prefectures of Tokyo, Kyoto, and Osaka, and 72 other prefectures. The Iwakura Embassy consisted of 46 delegates, 18 attending staff, and 43 students. Many of the delegates, while representing Japan, hailed from the western provinces which had toppled the Tokugawa shogunate in Edo, launched a new government seated in the Tokyo ("eastern capital") as Edo was renamed, and set out to nationalize what had been a lose confederation of local domains. The mission sailed from Yokohama on Meiji 4-11-12 (23 December 1871) and arrived in San Francisco on Meiji 4-12-6 (15 January 1872). The mission trained east to Washington, D.C., and crossed the Atlantic to London. From there the mission broke up into contingents that visited a dozen countries in Europe and the Mediterranian, and returned to Japan via several Southeast Asian and Chinese ports. According to one account, 107 members stepped off the train at Salt Lake City. Heavy snow forced them to stay two weeks -- longer at any single locality in the United States other than Washington, D.C. A decade later, the first in a continuing flow of immigrants from Japan arrived in the city. Most found work in railroad gangs, but in time many immigrants started farms and buisnesses. By the turn of the century, the Mormon Church was dispatching missionaries to Japan. The mission finally arrived in Washington, D.C. on 29 February 1872 (Meiji 5-1-21). The mission was in the United States from mid-January 1872 to early August 1872. The main delegation returned to Yokohama on 13 September 1873. FukudaIwakura Embassy chronologyThe itinerary of the Iwakura Embassy, covering the times and localities of interest here, is summarized in the following talbe.

SourcesKume Kunitake (1839-1931), a Saga domain retainer, accompanied the Iwakura Embassy as Ikawkura's personal secretary. In 1878 he compiled and published a five volume report of the mission, which dubs in English as "A true account of the American and European travels and observations of the extraordinary and plenipotentiary mission" (see Sources). Harue Tsutsumi has written a tight, lucid, informative, no-postmodernist-nonsense account of an 1879 kabuki production of the Iwakura mission story -- in which she argues as follows (Tsutsumi 2007, page 222, bracket hers; see full citation in Sources). From 1871 until 1873, Iwakura's delegation toured the United States and Europe during which they learned much about western civilization including opera, theater and other arts. Eight years later, Hyōryūki kitan-Seiyō kabuki [The Wanderer's Strange Story: a Western Kabuki], a kakbuki play written by kawatake Mokuami (1816-1893) and produced by Morita Kan'ya XII (1846-1897), the most progressive theater manager in the Meiji period, describes the progress of a group of Japanese visiting the United States and Europe. A clear parallel can be discerned beween the actual journey of the diplomats and politicians and the adventurous expedition portrayed in the fictional drama. it is very likely that the person responsible for the strong resemblance between the two journeys was Fukuchi Ōchi (1841-1906), one of the "first secretaries" of the embassy who became a prominent journalist in 1874, also known as an "advisor" for Kan'ya and Mokuami. I argue that this particular kabuki production reflects not only Ōchi's personal experiences abroad as a member of the Iwakura Embassy, but also his practical proposals, as a journalist, on how to westernize Japan. Harue Tsutsumi (堤春恵 Tsutsumi Harue) won the 44th Yomiuri Prize for Literature for a drama she wrote and produced called "Kanadehon Hamlet" (仮名手本ハムレット Kanadehon Hamuretto, 文藝春秋 Bungei Shunjū 1993, 195 pages, limited edition). The play is about Morita Kan'ya (XII, 1846-1897), one of the principle actors and promoters of kabuki during the Meiji period, and his dream of producing a kabuki version of Hamlet. Tsutsumi later became a student at the East Asian Languages Center of India University, where in 2004 she completed a doctoral dissertation called "Kabuki encounters the West: Morita Kan'ya's Shintomi-za productions, 1878-1879" (xii, 316 pages, Ann Arbor, MI, UMI, 2005). The hero of "Hyoryu kitan seiyo kabuki" is Shimzu no Mihozo 清水三保蔵 (Shimizu no Mihozō), a fisherman who is separated from his father when their boat wrecks. Resuced and brought to San Francisco by a steamship, he embarks on a journey to Washington, following the same route taken by the Iwakura Embassy. While crossing the desert plains, his train is attacked by Indians, and he is kidnapped by the chief. One adventure leads to another -- and to Europe, where Mihozo reunites with his father, Gozaemon, at an opera in Paris. The curtain closes with the two men agreeing that "Nothing is as deep as the kindness of people in other countries" (外国のお方ほど親しみの深いものはない). [Source: 日本演劇学界 Japanese Society for Theatre Research website] The kabukiization of the Iwakura mission has become Tsutsumi's standard story. In May 2006 she presented a talk at a meeting of the Japanese Society for Theatre Research called "The 'natives (indigenous people of America)' of Shintomiza" (新富座の "土人 (アメリカ原住民)" Shintomiza no 'dojin (Amerika genjūmin)'). Harue Tsutsumi 久米邦武編、田中彰校注 Kume Kunitake (compiler) Wendy Butler | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||