Romanization

I romanized the text of this story thinking I might include it in the Andon 80 article (Wetherall and Schreiber 2006), but there was no room. Here it is for the possible interest of some readers. Hyphens (-) at the end of a line show where a word wraps to the next line. Slashes (/) show breaks between sentences.

Meiji 9-nen 3-gatsu 2-ka ni Yokohama

Nakadori 1-chome no ryokaiya Sau-

da Kinsaku no uchi no detchi Asajiro wa 3-zen-

en no kin o saifu e iri docho 4-chome no ryo-

kaeya Chuuemon no mae o motte toori shi ni /

Chuuemon yobiiri nikai e age nyobo ya gejo

ni you o ihitsuke omote e idashi oki ki sono

mama ni Asajiro o kubirikoroshi

ura no komebitsu ni shigai o iri nawa de

girigiri to karagete oite / modo-

ri shi gejo ni ihitsuke 3-chome Anbee

no uchi e motase konnichi shindaikagiri o itasaru ni

tsuki / komebitsu hitotsu on-atsukari kudasare to moshi

ato de oroshitakou suru tsumori no

tokoro ten no ami nite roken ni oyobimashita

Commentary

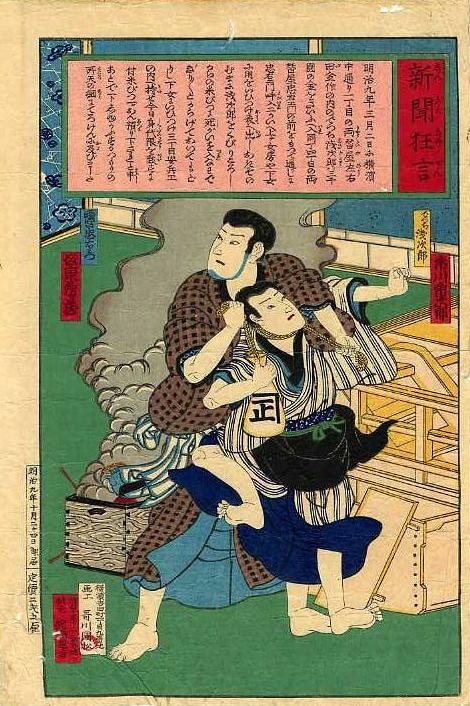

The print shows, right to left, the victim and the culprit.

Right: Apprentice Asajiro, played by Ichikawa Ichijiro.

Left: Amamiya Chuemon, played by Bando [Tsuruzo?].

The logo on Asajiro's money bag was probably meant to be read "kinshō" (if not "kaneshō" or even "kanemasa") and mean that the "gold" or "money" (kin / kane) is "genuine" (shō / masa).

The story represents a performance of a kabuki dramatization (‹¶Œ¾ kyōgen) of a murder incident which occurred in Yokohama on 2 March 1876. A seemingly shrewd money changer attempted to hide his heinous act. But fate caught up with as the tragicomedy became a morality play.

See Dramatizations of news for more examples of early Meiji prints that reflect how current events inspired theater.

Print particulars

The print of the Yokohama murder case was published on 24 October 1876, according to its notification (otodoke) date, which means the incident was adapted into a kabuki drama within about half a year.

Its marked price was 2-sen 5-rin (2.5 sen) -- which was about 0.5 over the usual price for a single-sheet oban print at the time. So it was not an advertisement for the performance but a souvenir, possibly sold at the theater as play guides are today.

The drama was probably part of a longer program. It may have been performed with a feature play or two -- the equivalent of a crime report in a newsreel at a movie theater before the age of televsion.

The drawer was Utagawa Kunimatsu (1855-1944) of Yokohama, Yoshidamachi, 1-chome 9-banchi. Kunimatsu, the son of Kunitsuru (1807-1878) and younger brother of Kunitsuru II, drew nishikie depicting customs and manners, world affairs, and newspaper illustrations. He went by various names, including Ichiryusai Toyoshige, Fukudo Kunimatsu, and later Gansho.

The publisher was Tsunajima Kamekichi of Asakusa, Kawaramachi, 12-banchi (now part of Asakusabashi). Tsunajima published several of Yoshitoshi's better known series.

Print information

Title: Shinbun kyogen

Date: 1876-10-24 (otodoke)

Publisher: Tsunajima Kamekichi

Drawer: Utagawa Kunimatsu

Carver: Unsigned

Writer: Unsigned

Size: Oban

Image: Yosha Bunko

Provenance

I bought this print from Seikado, a shop in Kyoto that deals mostly in old ceramics in 2005. The propritor said he came by the print in an exchange with another dealer. He knew only that it was part of a lot of around 100 prints. He speculated it had probably come from a collector in the area via a local dealer or "nokkaa" (knocker).

The expression is used to describe a person who knocks on doors and asks if people have anything they want to get rid of, whether to dump, recycle, or sell. They accept some things for free, other things for a fee. Knockers with an eye for antiques will pay small amounts for items they know they can sell for a lot more.

This inspired an idea for a short story, which I promptly wrote, built around a "knocker" who found some very valuable prints while doing some cleaning for a widow who had allowed her home to fill with junk and garbage after her husband died.

Principal sources

This print was first introduced on this website.

Yosha Bunko