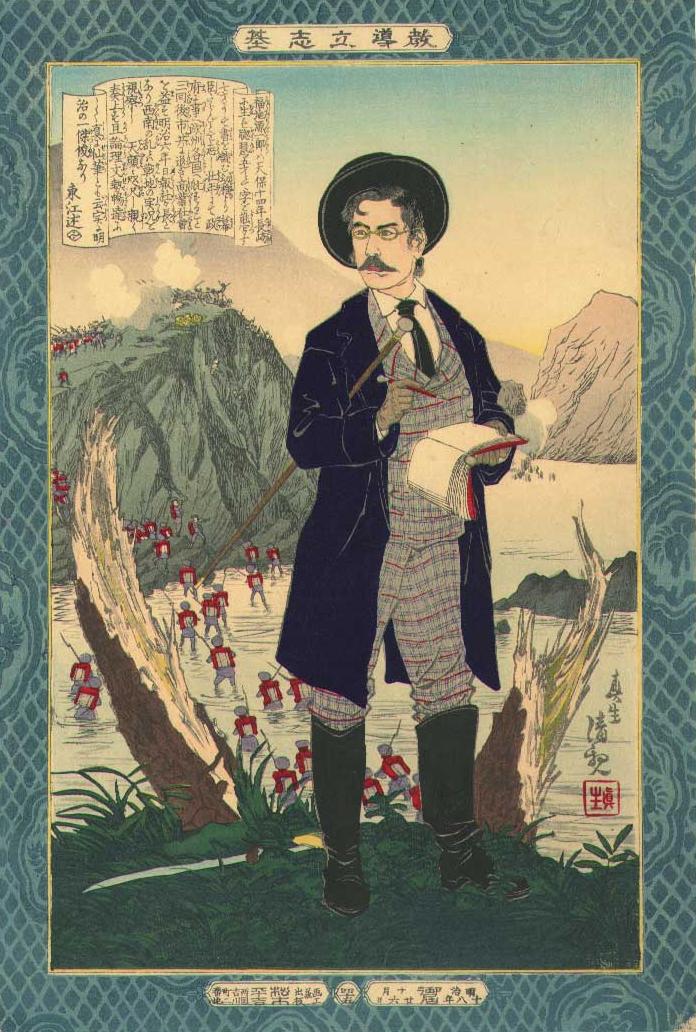

Kiyochika's Fukuchi portraitKobayashi Kiyochika (1847-1915), in a 1885 drawing, shows a booted, debonair Fukuchi standing in the wake of a battle still raging on another hill, as a column of imperial troops wades across an inlet to join the fight. This portrait was published by Matsuki Heikichi, who commissioned several drawers to contribute to a long-running series called Kyodo risshi no motoi. The series featured people who, as the title implies, were "Foundations of instruction and determination". Roger Keyes puts a typical "art history" spin on this portrait when comparing it with another print under the heading "Writers" in The Male Journey in Japanese Prints (Published in association with The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989, pages 120-121).

Never mind that Takarai Kikaku is hardly "dwarfed" by the landscape but looms in the foreground -- larger than the stairs, boats, buildings, bridge, and even the trees and clouds in the background. Never mind that Fukuchi Gen'ichiro is hardly "distanced" from the shattered trees in the foreground or from the sword at his feet -- as he stands on a height just swept by the battle still raging in the background. Never mind that these two prints were drawn and sold as commodities for different populations living half a century apart. Mind only that Keyes makes no attempt to illuminate the prints in their different commercial contexts, and is more interested in poetry, poets, and fan prints, than in journalism, journalists, and portrait prints. Mind only that his purpose is to indulge his fantasies about the mysteries of Japanese prints and otherwise free his imagination from the leashes of physical evidence. |

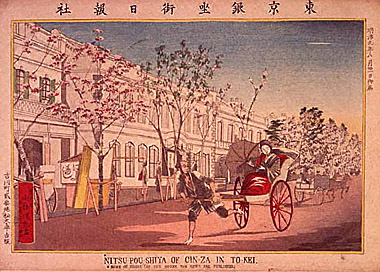

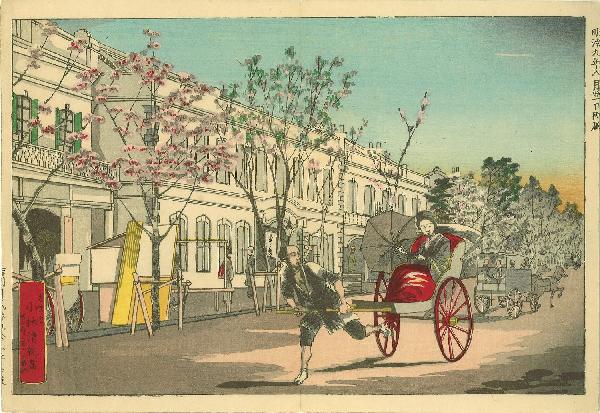

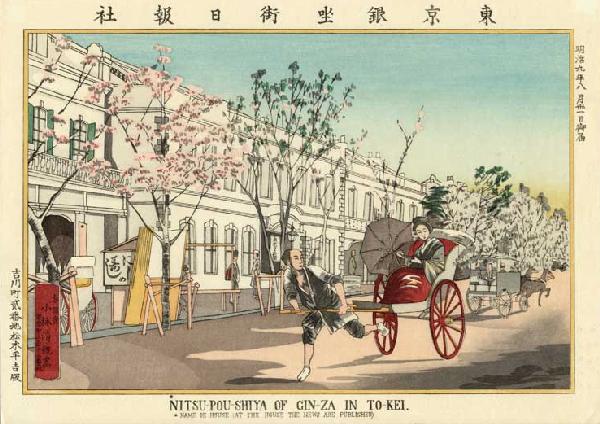

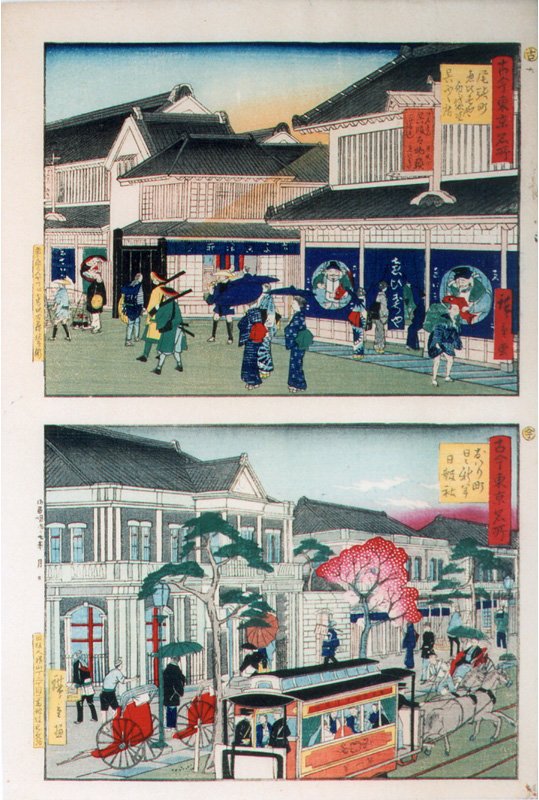

Kiyochika's Ginzagai NipposhaThe drawings of Nipposha to the right are different editions of one of the earlier of many horizontal single-sheet prints, designed between 1876 and 1881 by Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847-1915), showing famous sites in and around Tokyo. Ninety-three such drawings are known (Sakai 1973, Smith 1988:24). Many writers treat these drawings as a "series". However, lapses in publication activity and changes associated with each period of activity bely Smith's contention that "it retained a basic integrity of style that enables us to see it as a single sustained effort" (Smith 1988:24). In fact, the drawings are interesting precisely because they are not so uniform. "August" versus "31 August"The Nipposha drawing is one of five prints that represent the first of this kind. It and two others have a "Meiji 9-8-31" notification date. The other two have a "Meiji 9-8" date -- the year and month but no day. Smith and others feel that the two prints which lack "the exact day" were "in fact the very first, issued earlier the same month". But they could just as well have been issued after the prints with "the exact day" -- and those with "the exact day" of 31 August very likely were not issued on that day. All that can be reasonably said about this group of prints is that they came out roughly the same time, during August if not also November 1876. English title and glossThe first editions of four of the first five prints had an English title and gloss in the bottom margin. The Japanese and English titles, and the English gloss, on the Nipposha print are as follows. *NITSU-POU-SHIYA OF GIN-ZA IN TO-KEI. * NAME OF HOUSE (AT THE HOUSE THE NEWS ARE PUBLISHED) The romanization is precise and systematic. "Nitsu-pou-shiya" faithfully reflects the pronunciation of 日報社 (につぽうしや ni-tsu-po-u-shi-ya). "Gin-za" reflects 銀坐 (ぎんざ gi-n-za) -- as 銀座 was often written. The English explanation of Nipposha may not be idiomatic, but the grammar is not incorrect, and the description is precise. The question is -- who was the explanation for? TokeiThe English title gives the name of the city as "To-kei" -- a possible pronunciation of either 東京 or 東亰 -- as Tokyo's name was also written. Tonichi's masthead at the time, and until the paper became Mainichi Shinbun in 1943, was 東亰日日新聞 -- and, though not shown here, 新 was also written somewhat differently. On the drawing the paper's name is written 東京日々新聞. The more common romanizations of the name of Japan's capital, in English writing at the time, were "Tokio" and "Tokyo" representing とうきやお (To-u-ki-ya-o) -- now written とうきょう (to-u-kyo-u). But the linguistic name of the city -- what people called the city when speaking -- varied among Tokyoites and other native speakers and readers. Food for thoughtThe putative original editions of the first five prints had a heavy yellow border in addition to Japanese and English titles. The yellow borders and the English titles disappeared from early modified editions. Still later editions dropped the Japanese title and the notification date. Later editions were printed from partly or entirely recarved blocks. Designs were sometimes modified. Evidence of this is clearly seen in the putative second edition of the Nipposha print. The alleged first edition shows five hiragana on the side of the stand under the cherry tree. They read "nishime / sushi" -- which tells us what kind of food the vendor is selling. The kana are missing from later editions. That Tonichi's name remains on the door of the building makes sense because the building is the centerpiece of the drawing. Why, though, were the words on the vending stand dropped? If not merely an oversight, I would guess that the publisher, or Kiyochika himself, decided that the names of the food were too large, too conspicuous, too distracting. Similar flawsIn the upper right corner of both the putative original with English titles, and the modification with no titles and sign on the food stand, is what appears to be the same flaw in the block used to print the blue sky. Other holdingsA copy of the early reissue of Ginzagai Nipposha (as shown in the image copped and croppsed from Hara Shobo) was apparently exhibited at Gunma Prefectural Museum of Modern Art in 1986, and a black-and-white image is shown in the exhibition catalog (see review in Bibliography). The catalog attributed the copy to Kanagawa Prefectural Museum. |

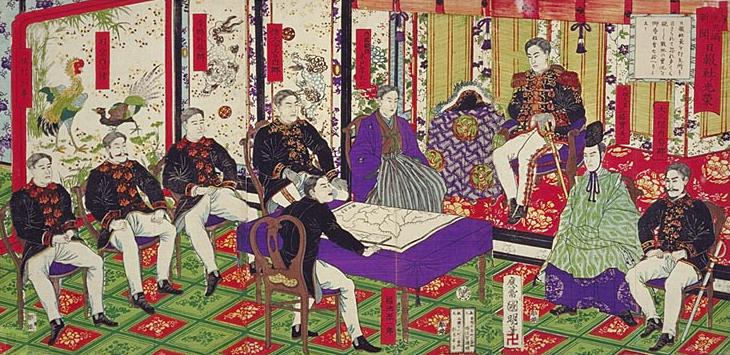

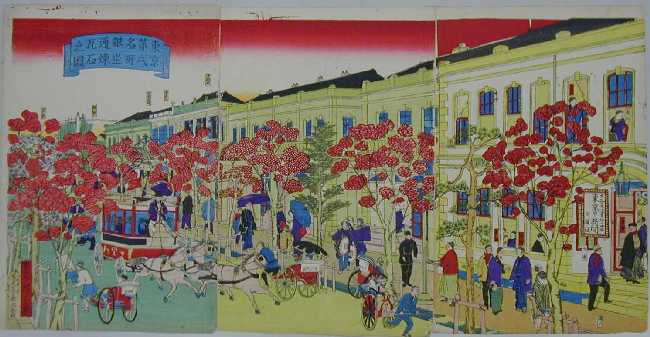

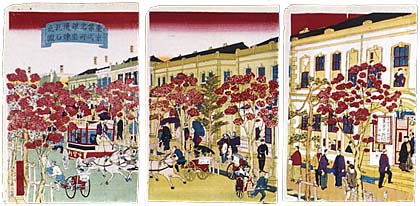

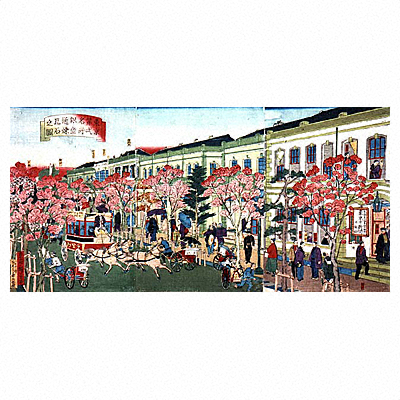

Hiroshige III's Ginzadori NipposhaTo the right are variations of a triptych titled "Tokyo daiichi meisho Ginzadori rengaseki no zu" (東京第弌名所 / 銀坐通煉瓦石之圖) or "Picture of Tokyo Number One famous spot Ginzadori brickstones". It was published in 1877 or 1878 by Gusokuya Kahee, who had recently produced the series of news nishikie drawn by Yoshiiku and written by Sansantei Arindo and other Tonichi illuminaries. The drawing is signed by Hiroshige -- the III, aka as Shigemasa (c1843-1894). NipposhaThe triptych features -- in the foreground of the perspective -- the Nipposha building and some of the company's more famous employees. In the windows, on the sidewalk in front, and on the steps or at the entrance are images of the men named in the cartouches -- Arindo, Hokiyama, Hirooka, Nishida, Yoshiiku, Ginko, Gosō (alluding to Fukuchi, who began some of his editorials with "We"), and Sasanami. The vertical sign at the entrance reads "Dajokan kiji insatsu goyo / Tokyo [Tokei] nichinichi shinbun / Nipposha" (太政官記事印刷御用 / 東亰日〃新聞闻 / 日報社). The paper is described as "Agent for publishing articles from [reports of] Dajokan" -- the equivalent of today's Cabinet. The entire print is a not-so-quiet testimony to the repute of the paper and its publishers on Tokyo's most famous boulevard. Moves and name changesNipposha moved four times, and changed its name twice, from its start in 1872, to its often pictured Ginza locales in 1874 and 1877. Asakusa Kayacho 1-chome officeNipposha began operations out of the home of Jono Denpei, one of its founders, at Asakusa Kayacho 1-chome, now part of Asakusabashi in Taito-ku. Tonichi's first twenty issues (Meiji 5-2-21 to 3-10) were published from this location. Moto-Osakacho Shinmichi officeFrom Issue 21 (Meiji 5-3-12), Tonichi was published from a facility at Moto-Osakacho Shinmichi, now in the vicinity of Nihonbashi Ningyocho 1-1-17. Mainichi's centennial chronology states that Nipposha moved to this locale on 3-6, but this may refer to the edition of the paper that carried the notice (Mainichi 1972:583). The facility was a printshop and bookstore owned by Tsuji Den'emon and managed by Nishida Densuke, one of Nipposha's founders. The Tsuji family had bought a used foot press for 750 yen, which Tonichi used to print its daily run of about 2,000 copies. Concomitant with this move, Nipposha was renamed Nippo Kaisha. Asakusa Gomongai Kawaracho 16-banchiFrom Issue 300, dated Meiji 6-2-25 (25 February 1874), Tonichi was published from the company's third location -- Asakusa Gomongai Kawaracho [Kawaramachi] 16-banchi. The 21 February edition announced that the office saying it would be on the 24th, so there would be no paper that day (Mainichi 1972:583). The place, which the company rented, was where the Iseya (Aoji) Shirozaemon rice agency had been. Nishida's father had been a rice agent, and Iseya had been next door, according to Nishida's reminiscence in Tonichi's 31 March 1909 edition (Imayoshi 1988:55).

On this occassion, the company again became Nipposha. Kyobashi Ginza 2-chome officeWithin a year, Tonichi's circulation had jumped to between 5,000 and 6,000. Again, it was time to move into a larger office. Nipposha has rented all the buildings it had occupied since leaving Jono's home. It was now in a position to buy -- and it bought big. On 11 May 1874 the company moved into a new, two-story brick edifice on the east side of the main street at Ginza 2-chome 3-banchi. An report about the move appeared in the following day's paper (Mainichi 1972:339). This building is the subject of Hiroshige III's Ginzadori triptych. Oharicho 1-chome officeNipposha moved down Ginza street several blocks into a new building on the corder of Oharicho 1-chome in the building on the last day of 1876 (Mainichi 1972:583), and so Tonichi's first issue of 1877 was edited from what was then -- apparently -- the largest brick building on the avenue. 1872 fire and reconstructionOn the 26th of the 2nd month of Meiji 5 (3 April 1872), a mere five days after Tonichi's start, a fire swept through the heart of Ginza, destroying most buildings in Kyobashi, Ginza, and Tsukiji. The fire destroyed buildings in 41 neighborhoods, affecting 19,872 people, killing 8 and injuring 65. Four days after the fire, the Dajokan, the highest government organ at the time, instructed the Tokyo-fu to rebuild the street with brick buildings. Tokyo governor Yuri Kosei (Yuri Kimimasa, aka Mitsuoka Hachiro, 1829-1909), commissioned Thomas James Walters (1842-1892), an Irish architect in the employ of the Ministry of Finance, to rebuild Ginza in the Georgian style then popular in London. Walters also set up a brick factory and supervised the construction. The brick buildings that emerged from Ginza's ashes attracted people from all over the city. Ginza's streets were musts to see for anyone visiting Tokyo from other parts of Japan, even other countries. Tonichi's recognizable name -- and the association of Nipposha with the halls of power that were able to raise such splendor from Ginza's ruins -- made the Nipposha building an easily sold subject of souvenir woodblock prints featuring famous spots in the city. The new GinzaThe new boulevard -- its sidewalks lined with cherry trees and willows -- was full of pedestrians in all kinds of dress, jinrikisha taxis enroute and waiting, a horse-and-buggy, and a four-horse omnibus. The street was served by a four-horse Senriken bus that ran between Asakusa and Shinbashi. The bodies of the original buses had two levels, but as there had been many accidents, the upper levels were removed, hence the single-level bus shown in the triptych. The Senriken company folded in 1886, but Senriken survives today in the name of a Ginza karaoke club. VariationsAs seen in the images here, the Ginzadori triptych was published in at least three differently colored editions. Yellow cartouche editionAll images associated with Tonichi and/or Mainichi publications appear to be of the same edition, with a a yellow cartouche and green foreground. The front and back end papers of Soma 1941, a Tonichi publication celebrating the paper's 70th anniversary, show a miniature reproduction of this edition. All these images are possibly of the same print -- perhaps from the Araya Bunko at Mainichi Shinbun. Blue cartouche editionThe Tokyo Central Metropolitan Library (Special Collections Room) and Dentsu Advertising Museum images appear to be of the same edition. The odd mix of foreground colors suggests that they may even be the same print. The Dentsu Museum link is now dead. Moreover, the caption on the vanished Dentsu site -- in replacing unfamiliar older characters with more familiar forms -- incorrectly read 弌 as ニ -- turning the title into the "second" (弐) rather than "first" (弌) famous scenic spot. Polychrome cartouche editionThe edition with the polychrome cartouche -- attributed by Professor Mikami Yoshiki at Nagaoka University of Technology to Shimizu Corporation -- is possibly the original edition. The forground is a consistent darker green. The sidewalk is a clearly contrasting brown. The buildings are of a uniform color. |

Hiroshige III's Oharicho NipposhaBy 1876, Nipposha had outgrown its Ginza 2-chome office and was looking for a new location. Fukuchi Gen'ichiro was given an opportunity to by a corner lot in Oharicho 1-chome -- some 400 tsubo of land that had been the site of the Ebisuya store but was then owned by the Ministry of Finance, for which Fukuchi had once worked. The price would be 15,000 yen -- and Fukuchi was unable to talk the Minister of Finance, Osumi Shigenobu (1838-1922), into reducing the prince. According to Nishida Densuke, reminiscing in Tonichi's 10,000th issue on 10 November 1904, Osumi told Fukuchi not to talk foolish. The brick building had cost 150 yen a tsubo, there were five jizo in back and some in front protecting it, and over 450 tsubo of land under it. Fukuchi paid off the entire amount in three years, at the rate of about 500 a month, or 5,000 a year. The circulation of the paper at the time was between 7,000 and 8,000 and monthly subscriptions cost 17 sen. The site of the new Nipposha office was Oharicho 1-chome 1-banchi in Kyobashi-ku. This is now the New Melsa mall at Ginza 5-7-10 on Chuo-dori west of its Ginza 4-chome intersection with Ome-dori. Nipposha moved to Oharicho on the last day of 1876 (Mainichi 1972:583), and the 4 January 1877 issue was the first to be edited from the new building (Ibid. 341). A number of photographs of Nipposha's Oharicho building have been published. Kiyochika also drew it for a supplement distributed with the 2 November 1892 (No. 6317) edition of the paper (Mainichi 1972:337). |