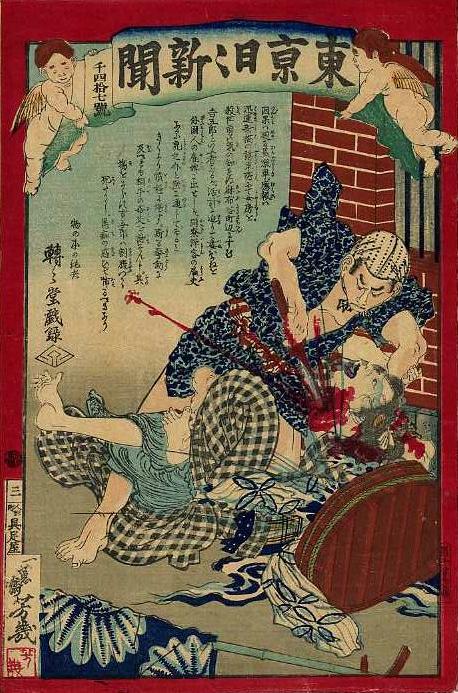

Tokyo nichinichi shinbun See another version of this story in "Cause-and-effect is a land steamer that goes around. And retribution was swift at the station in Shinbashi where a man called Kichigoro killed his wife. He lived in the vicinity of Tanimachi in Azabu and did not know feelings. Pressed for money to live on, he sent his wife Okane to work as a maid for an outlander, and she secretly took up with Toranosuke, who was the servant of the same overseas visitor (alien) [ijin (yōkyaku) �ِl]. After hearing there was [another man] he could not contain his rage, and having come to such an act [of killing his wife], he struck and injured the opponent man (adulterer) [graphs=kanpu, reading=otoko]. Not leaving the place, Kichigoro cut and ripped his belly [graphs=kappuku, reading=harakakiyabutte] and died. The perplexity of ignorance is truly terrifying [guchi no madoi zo osoru beki nari]." Tentendō [Translated by William Wetherall] |

Cause-and-effect . . . goes around

Tentendō has substituted "land steamer" for "wheel" in the phrase cause-and-affect [fate, fortune] is a wheel that goes around, which reflects "ingwa wa megurumu oguruma" (���ʂ͉�鏬��). The phrase that immediately follows this phrase is expected, but Tentendō writes "mukui wa hayaki" (�����n�v��), and the "ki" makes "retribution is swift" attributive to Shinbashi station.

This is a good example of the double bind of grammar and narrative style in translation. Translating only the grammar would result in something like "As for the man who killed his wife at Shinbashi station, where fate was a steam train that went around, and retribution was swift, he . . . ." But translating Tentendō's narrative style requires fidelity, both to the order in which he presents the elements of his story, and to the rhythms in which he makes these elements flow in the stream of the narrative, which is intended to be "heard" if recited.

As Satō Kenji points out, "the opening with the 7-5 phrasing beginning 'Inga wa meguru okujouki, mukai wa hayaki shinbashi no . . .' sounds nice and the rhythm is pleasant to the ear" (Nyuusu no tanjō).

"7-5 phrasing" refers to the number of morae (not syllables) in phrases that alternate 7-5-7-5-7 morae. This alteration harks back to the oral tradition of the longer epic poems recorded in the 8th-century anthology Man'yoshu.

The first several lines of Tentendō's narration follow this old and familiar pattern.

7 -- ingwa wa meguru

5 -- okajouki

7 -- mukui wa hayaki

5 -- shinbashi no

7 -- suteishon nite

Tentendō wrote "hot-air (steam) train" or "jōkisha" (���D��) [4 morae], but he glossed the characters "okajōki" (�������悤��) [or "land steamer" (�����C) [���D��] [5 morae] in order to get the rhythm he wanted. This and similar examples dramatize the fact that what ultimately controls a story is the "language" in which it is intended to be recited, and not the "script" in which it may be written.

Linguistics 101

A word in a spoken language consists of sounds that people who know the language associate with meanings. A speaker utters sounds with certain meanings in mind, and the listener hears the sounds with the same meanings -- to the extent that the speaker and the listener share the associations between the sounds and the meanings.

When writing a word using phonetic script such as kana, the script represents the sounds. Writers speak the sounds through their brushes, pens, or keyboards, and readers hear the sounds through their eyes, or through their fingers if the text is in braille. And, as in the case of oral-aural communication, the meanings that the reader imputes to words written in phonetic script will be the same as those intended by the writer -- with, again, the caveat that the writer and the reader share the associations between the sounds and the meanings.

Graphic script like kanji have both phonetic and semantic qualities that sllow them to be used with one, the other, or both qualities. RESUME for When writing a word with script like kanji, which represent the word it means, and therefore elicit the sounds of the word, or (2) represent different words with common sounds, (3) represent different sounds with common meanings.

There are cases in which, even when the pronunciation of a graphic expression is not lingistically marked, the expression will be recited according to a reading that satisfies the contextual linguistic (moraic) constraints. Readers of ������ in the lyrics of a song, for example, are supposed to know that the graphic expression ������ can represent either Sino-Japanese "ko-n-ke-tsu-ji" (5 morae) or Japanese "a-i-no-ko" (4 morae), and be able to judge which of these words is required by the lyrics.

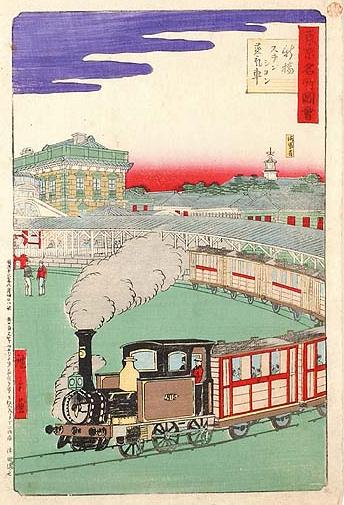

Tentendō also used a contemporary abbreviation for "steamship on land" or "oka no jōkisen" (���̏��C�D). The name for this new mode of transportation was later shortened from "jōkisha" (���C��) to just "kisha" (�D��). With the development and spread of new engine technologies, the coal-burning locomotives were replaced by diesel trains (kidōsha �C���ԁAdiiseru dōsha �f�B�[�[�����ԁAdiiseru kaa �f�B�[�[���E�J�[) and electric trains (densha �d��).

The closing of Tentendō's story blames the murder-suicide on an affliction (madoi (�f��) of ignorance (guchi ��s), which in Buddhism is one of the three poisons (sandoku �O��) or perplexions (bonnō �ϔY) of the spirit -- "ton" (��), "jin" (��), and "chi" (ᗁA�s) -- the other two being avarice (donyoku �×~) and malice (shinni �ќ�). This brings the story full circle to the opening declaration, that there is no escaping the effects of cause.

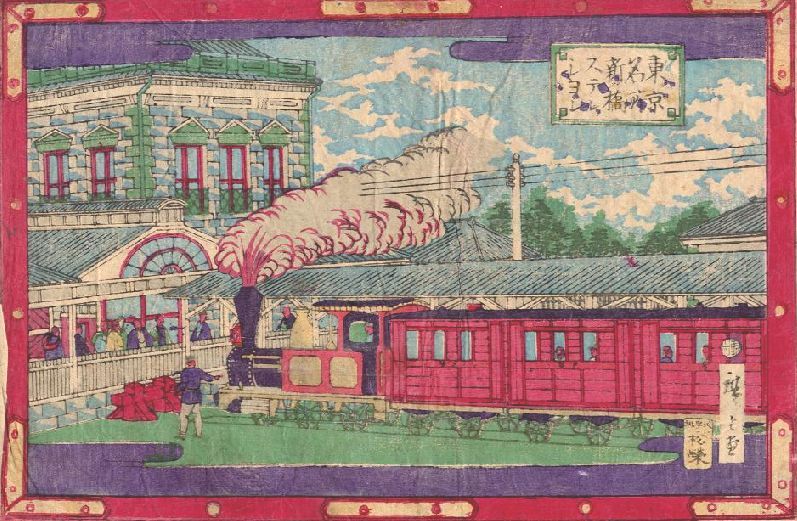

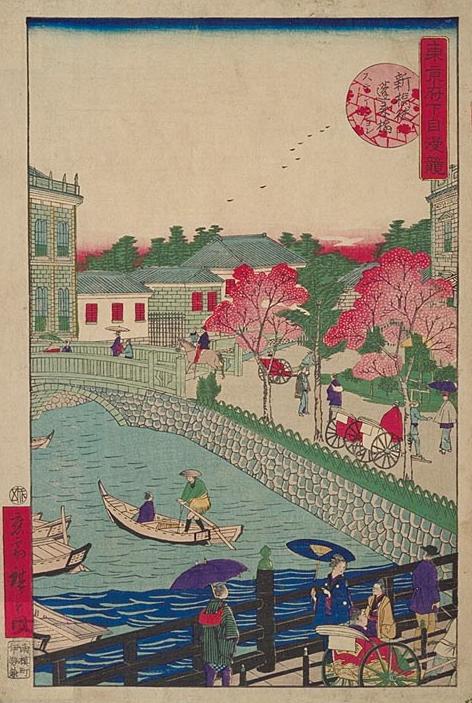

station in Shinbashi

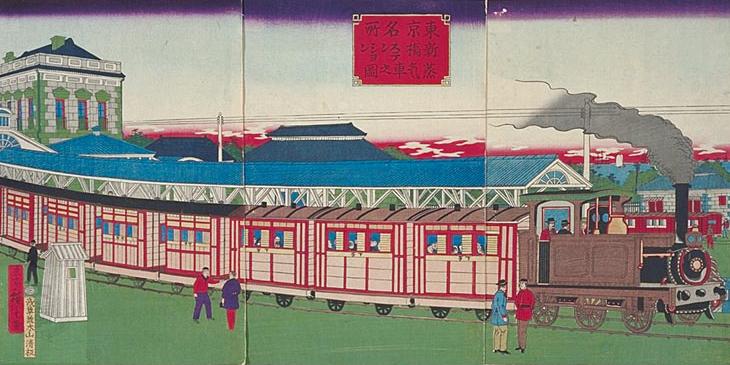

The first train in Japan was built between Yokohama and Shinbashi. The Yokohama-Shinagawa leg began operating on 13 June 1872 (Meiji 5-5-8) after a ceremony the previous day. Service to the terminal at Shinbashi, constructed at Shiodome, then much closer to the shore of Tokyo bay, began on 15 October (Meiji 5-9-13), again after a ceremony the previous day.

The line was built to accommodate the movement of people and goods between Yokohama, where foreign ships arrived, and Tsukiji, where a foreign settlement and hotels for foreigners had been built in Edo, in addition to the foreign settlement and related facilities in Yokohama. Shinbashi station was built on land obtained by commandeering and relocating the residences of several shizoku and other families and shipping agents in the area.

What today is called Shinbashi "eki" (�w) was called Shinbashi "teishajo" or "stop-train-place" (��ԏ�). Tentendō wrote "keishajo" or "rest-train-place" (�e�ԏ�), but glossed the graphs "suteishon" (���Ă������) [�e�ԏ�] -- a rare example of a kanaization of an English word in a news nishikie story. Contemporary newspapers, including Tōkyō nichinichi shinbun, who Tentendō w

Shinbashi was the terminal of the Tokkaido line until 1914 when Tokyo station was built. A new station was also built at Shinbashi, where the line was shifted a bit. The old station was torn down and the yard converted to a freight terminal called Shiodome-eki.

By the 1980s the yard was no longer being used and was sold for commercial development. Remnants of the original station were excavated in the 1990s when the site was made a national monument. A restored "Kyu Shinbashi Teishajo" now stands a couple of minutes walk from the present station. In the building is a railway history exhibition and a restaurant.

Print information

Size oban

Series: Tokyo nichinichi shinbun

Issue: 1047 [TNS 1875-6-22]

Number 3

Approval seal: 1875-8

Drawer: Ikkeisai Yoshiiku

Writer: Tentendo (Writer of the source of things)

Carver: Horiko Eizo

Publisher: Gusokuya (Ningyocho)

Principal sources

Yosha Bunko, Ono Collection, Ono 1972:168 (Plate 77), Sato 1999 (Nyuusu no tanjo).