Stephen F. Soitos, 1996

The Blues Detective

Yosha Bunko scan

|

Stephen F. Soitos

The Blues Detective

(A Study of African American Detective Fiction)

Amherst: The University of Massachusetts Press, 1996

x, 260 pages, hardcover

Let me raise a question about "authenticity": can whites or yellows write black characters? No, if you assume that race somehow exists in such a way that makes it impossible for a writer to put oneself in the skin of another color. No, if you assume that someone who has never committed serial murder can create a credible serial murderer. No, if you assume that one human being can't possibly understand another.

Put another way: can a New England landscape painter, from an Azorean, Portuguese family, credibly write about black detective fiction, simply because James Baldwin, whom he met and befriended at the University of Massachusetts while earning a Masters of Fine Arts, helped him reflect on the following three questions, among others (page xi)?

How many African American authors had written detective novels with conscious reworking of detective tropes? Why had African American authors chosen the detective form? Did the evidence of the black detective novel suggest important revisions of the detective personas and use what I call double-consciousness detective themes?

Soitos considers his book a work of literary history and criticism contrived to answer such questions. As he plunged deeper into the history of black detective fiction, partly inspired by Frankie Y. Bailey's Out of the Woodpile: Black Characters in Crime and Detective Fiction (Westport: Greenwood, 1991), and by his own search for stories that predated known black detective novels, it became impossible for him not to focus "solely on African American authors whose works include or make strong reference to black detectives and the detective tradition" (page xi). As he did so, it became clear to him that (page xi)

. . . an important aspect of popular culture transformation was contained in African American creations using detective motifs and formulas. By using a white Euro-American popular culture form, black authors created important new tropes in black detective fiction.

He was still, as he put it, in a maze. He had some links and clues, but lacked "a theoretical approach to my intuitions and discoveries." Certain English lit professors who were making a name for themselves in the emerging field of "African American literature and critical theory" provided him with an approach that "judges African American detective texts on their own merits."

Soitos assures the "perceptive reader" that "new critical theory" is not alienating but "enriches the appreciation of African American expressive arts creations" and more (page xii).

Vernacular criticism is an exciting and enlightening tool that can be used for support and defense of the heritage of African Americans and their humanitarian and community values. This type of criticism helps to connect the varied and powerful creations of African Americans by developing a critical vocabulary based not on Euro-Americentric models but on African American and Afrocentric worldviews. . . .

I believe vernacular criticism illuminates rather than obfuscates texts by focusing on a matrix of African American expressions that conclusively affirm the positive and unique contributions of African American culture. . . . Writing The Blues Detective enabled me to discover ways that postmodern criticism can be applied to popular culture forms. . . .

Four tropes

Soitos contends that, while "on the surface African American sensibilities and the hardboiled school of detective fiction would seem to have little in common . . . black detective writers use African American detective tropes on both classical and hardboiled detective conventions to create a new type of detective fiction" (page 3). His operating word is "tropes" (page 4).

My conception of "tropes" somewhat amplifies M. H. Abrams's definition as "words or phrases . . . used in a way that effects a conspicuous change in what we take to be their standard meaning" (64). In my usage tropes are associated with figures of thought, and effect conspicuous changes on detective conventions in the areas of the detective persona, double consciousness, black vernaculars, and hoodoo, as well as presenting issues of black nationalism and race pride in new ways. These four tropes help to define a coherent worldview shared by African American authors using the detective form.3

Black no more

Shared, but not by all. Soitos examines the works of "African American authors such as Pauline Hopkins, J. E. Bruce, Rudolph Fisher, Chester Himes, Ishmael Reed, and Clarence Major" (page 3). A footnote to this list explains why one black writer didn't make his cut (page 237, note 2).

2. It must be noted here that there is one black author who wrote black detective fiction with a series of black detectives that I have chosen not to examine. George Schuyler (1895-1977), best known for his novel Black No More (1931), wrote six detective short stories for the Pittsburgh Courier during the years 1933-39. These stories were published under his own name as well as under the pseudonyms William Stockton, Samuel I. Brooks, and Rachel Call. After reviewing this detective fiction, I found that Schuyler's work proves the rule of African American detective tropes by way of exception. Schuyler's detective fiction does feature a series of black male detectives, but they hardly break new ground in African American detective personas, as they are usually "tall, powerful and handsome" with no other defining characteristics. The stories themselves are routinely executed in the classical detective mode in the most elementary fashion. Schuyler wrote these stories without a modicum of the satire, comic relief, or insight into black life that make his novel Black No More so interesting. Some of the stories take place in Harlem but add nothing to the depiction of that community or its culture. Most troublesome is Schuyler's negative depiction of aspects of African American culture. In "The Beast of Broadhurst Avenue: A Gripping Tale of Adventure in the Heart of Harlem" (Pittsburgh Courier, Mar. 3, 1934-May 19, 1934), Schuyler, writing as Samuel I. Brooks, describes a hoodoo ceremony as "rigmarole," full of "grotesqueness." He tells us that an African tribe, the Guro, were "recently cannibals" and that an African sculpture was an "amazingly ugly African image about 3 feet high." The evil professor of the story, trying to transplant an African American brain to the skull of a great dog, says, "Yes, the female Negro brain because of its small size was best adopted for my purposes." A complete list of Schuyler's short fiction published in the Courier is given in the reprinted issue of Schuyler's novel Black Empire (1991).

This partly answers the question of "authenticity" I raised, somehwhat tongue-in-cheek, at the outset. Apparently being black does not itself qualify an author as a credible narrator of "black culture" -- particular if the author waxes "negative" about anything Soitos regards as integral to blackness.

But what about white or yellow authors who avoid "typical depictions of blacks as lazy and dishonest" (page 71), who mime the tropes that supposedly "define a coherent worldview shared by African American authors" (page 4), and who write detective fiction with "race, class, and gender" issues in mind (page 5)? Would they pass as bona fide writers of "black detective fiction" in Soitos' esteemed postmodernist view? (WW)

Top

|

|

The Asian American Writers' Workshop

The Asian American Writers' Workshop (AAWW) was founded in New York in 1991 to support "writers, literature and community." Among other activities, each winter it presents "The Annual Asian American Literary Awards Ceremony to recognize outstanding literary works by Americans of Asian descent." This is in accord with its Mission Statement as "a national not-for-profit arts organization devoted to the creating, publishing, developing and disseminating of creative writing by Asian Americans."

Top

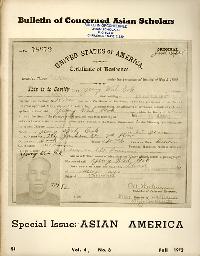

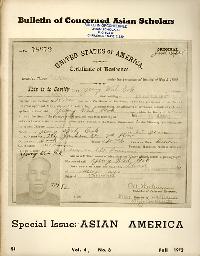

Nee, Nee, Yu, and Wong, Fall 1972

Special Issue: ASIAN AMERICA

Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars

Yosha Bunko scan

|

Victor and Brett Nee, Connie Young Yu, and

Shawn Hsu Wong (special editors of this issue)

"Special Issue: ASIAN AMERICA"

Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars

San Francisco (CA): Fall 1972, Vol. 4, No. 3

70 pages, softcover

This may be the first time any academic journal devoted an entire issue to Asian America with a focus on literature. Most of the contributors are writers and students of fiction and poetry, and five of nine contributions concern literature.

Frank Chin, Jeffery Paul Chan, Lawson Fusao Inada, and Shawn Hsu Wong teamed up to write "Aiieeee! An Introduction to Asian-American Writing" (pages 34-46) -- a warm up for their famous anthology, Aiieeee! (1974).

Wong, who went on to edit Yardbird Reader Volume 3 (1974) with Frank Chin, also contributed a book review and a poem, and teamed with Connie Young Yu to introduce excerpts from a Japanese American concentration camp journal called "Trek" (pages 48-55).

And Frank Chin, who had just just won a prize for his play "The Chickencoop Chinaman" (1972) and been a writer-in-residence at the University of California at Berkeley (Spring 1972), contributed "Confessions of the Chinatown Cowboy" (pages 58-70). The following year, another version of this piece called "Confessions of a Number One Son" was featured as the "Charlie Chan in America" cover story of Ramparts (March 1973, Volume 11, Number 9, pages 42-48). (WW)

Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars

BCAS, published since 1968, has been called Critical Asian Studies (CAS) since Volume 33, 2001. It was originally the publication of the Committee of Concerned Asian Scholars, which formed "in opposition to the brutal aggression of the United States in Vietnam and to the complicity or silence of our profession with regard to that policy" (page 55).

The editorial board at the time this issue on Asian America was published consisted of Rod Aya, Frank Baldwin, Marianne Bastid, Herbert Bix, Helen Chauncey, Noam Chomsky, John Dower, Kathleen Gough, Richard Kagan, Huynh Kim Khanh, Perry Link, Johnathan Mirsky, Victor Nee, Felicia Oldfather, Gail Omvedt, James Peck, Franz Schurmann, Mark Selden, Hari Sharma, and Yamashita Tatsuo. A number of these scholars are still on CAS's editorial or advisory boards.

Now a slick journal published by the Taylor & Francis Group at Routledge, at the time this special issue on Asian America was put together, editors were still inserting a few amendments and corrections by hand in the typeset copy. (WW)

|

Top

Can, Chin, Inada, and Wong, 1991

The Big Aiiieeeee!

Yosha Bunko scan

|

Jeffery Paul Chan, Frank Chin, Lawson Fusao Inada, Shawn Wong (editors)

The Big Aiiieeeee!

(An Anthology of Chinese American and Japanese American Literature)

New York: Meridian Books (Penguin), 1991

619 pages, paperback

This is not a reissue of the original Aiiieeeee. Though it also includes excerpts from Louis Chu's Eat a Bowl of Tea and John Okada's No-No Boy, all its content is new.

Frank Chin's introductory essay, "Come All Ye Asian American Writers of the Real and the Fake" (pages 1-92), is the most controversial contribution of this anthology. In it, Chin remarks that "If all the white Spaniards were to disappear off the face of Spain right now, the gypsies and flamenco would not lose anything that holds them together. The gypsies would still be gypsy, and the flamenco would be flamenco. The only difference would be that they would have more room to grow."

Chin contends the same cannot be said for Asian Americans born in the United States "between 1882 and at least 1966" (page 2).

What if all the whites were to vanish from the American hemisphere, right now? No more whites to push us around, or to be afraid of, or to try to impress, or to prove ourselves to. What do we Asian Americans, Chinese Americans, Japanese Americans, Indo-Chinese, and Korean Americans have to hold us together? What is "Asian America," "Chinese America," and "Japanese America"? For, no matter how white we dress, speak, and behave, we will never be white. . . .

What Chin means by this is that, if whites disappear, and "Asian Americans" no longer need to prove themselves to anyone, much of what is regarded as "Asian American" will no longer have any meaning -- since, in his well-known view, the "Asian American" literature that is popular among whites -- Maxine Hong Kingston's Woman Warrior, David Henry Hwang's M. Butterfly, Amy Tan's The Joy Luck Club -- are fakes contrived by writers catering to white expectations of what Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, or whatever "Asian" or "Oriental" culture should be like.

This second anthology by the same editors who brought out Aiiieeeee! in the 1970s, when the voices of such critical writers were making themselves more widely heard, goes even further in intentionally not including examples of "Asian American" literature they consider to be as phony as Charlie Chan.

Some commentators have scolded the editors for letting their politics get in the way of producing an anthology that included some of the more popular Asian American authors. My rebuttal to this would be that, precisely because the editors have excluded the writers who have been most favored by New York publishers whose bottom lines depend on readers with Oriental fetishes -- The Big Aiiieeeee! is packed with more examples of better writing. (WW)

|

Top

|

|

|

Frank Chin, Jeffery Paul Chan, Lawson Fusao Inada, Shawn Wong (editors)

1974 and 1991 editions of Aiiieeeee!

Yosha Bunko scans

|

Frank Chin, Jeffery Paul Chan, Lawson Fusao Inada, Shawn Wong (editors)

Aiiieeeee!

(An Anthology of Asian American Writers)

1974 edition

Washington, D.C.: Howard University Press, 1974

xviii, 200 pages, hardcover

1991 edition

New York: Mentor (Penguin Books), 1991

xli, 294 pages, paperback

With a new Preface by the editors

"Aiiieeeee" represents the screams of Asians who appear in American movies, tv dramas, and comic books mostly as bad guys who lose or die, or as caricatures of good guys who have a limited English vocabulary.

This is the most famous anthology of its kind -- intended to represent what the editors considered in the early 1970s to be the most authentic "voices" in Asian American literature -- as opposed to those that were merely feeding the white mainstream with confirmations of its stereotypes.

Editor profiles

Here are some notes I've complied on the editors, all of whom are still active as writers and teachers.

Frank Chin, a playwright, was born in Berkeley in 1940 and is the best known of the four Aiiieeeee editors. He first produced Chickencoop Chinaman (1971), his now classic play, in 1972. By now the author of other plays and several novels, Chin has stirred considerable controversy over his criticism of what he calls "fake" Asian American literature.

Jeffrey Paul Chan was chairman of the Asian American Studies Department at San Francisco State University at the time Aiiieeeee! was published. His fiction includes the novel Eat Everything Before You Die: A Chinaman in the Counterculture (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2004).

Lawson Fusao Inada, a poet, was born in Fresno in 1938 and spent the years 1942-1945 in Arkansas and Colorado concentration camps for Americans and others of Japanese descent. An associate professor of English at Southern Oregon College at the time Aiiieeeee! was published, Inada had already published a collection of poetry called Before the War (Morrow, 1971), for which he remains best known. Since then he has published Legends From Camp (Coffee House Press, 1993) and Drawing the Line (Coffee House Press, 1997), also collections of his own poetry, and has edited Only What We Could Carry: The Japanese American Internment Experience (California Historical Society, Heyday Books, 2000).

Shawn Wong was born in Oakland in 1949. An instructor at Mills College in Oakland when this anthology was published, he later became a professor of English at the University of Washington. Wong is the author of two novels, Homebase (Reed and Cannon, 1979) and American Knees (Simon & Schuster, 1995; Scribner paperback, 1996; University of Washington Press, 2005). A film version called Americanese, directed by Eric Byler, premiered in 2006 at several film festivals.

Racist love

In a 1972 essay called "Racist Love" (Richard Kostelanetz, Seeing Through Shuck, New York: Ballantine Books, pages 65-79), Frank Chin and Jeffrey Paul Chan coined the expression "racist love" as a counterpart of "racist hate" -- to designate the ways in which Asians are considered "acceptable" to whites who might otherwise hate them. Charlie Chan, for example, has mostly been loved as an affable, effeminate, fake Confucianist. (WW)

|

Top

Jessica Hagedorn, 1993

Charlie Chan Is Dead

Yosha Bunko scan

|

Jessica Hagedorn (editor)

Charlie Chan Is Dead

(An Anthology of Contemporary Asian American Fiction)

New York: Penguin Books, 1993

xxx, 572 pages, paperback

Jessica Hagedorn is a poet and novelist, as well as a performance artist. As she explains in her Introduction, she came to United States from the Philippines in the early 1960s, with her family, which settled in San Francisco. She thanks god for the other Asian American writers who became her "streetwise teachers, co-conspirators, and artistic family in the blossoming Bay Area of the 1970s" (page xxv).

The blossoming of Asian American literature that came in the wake of the ethnic studies movements in the late 1960s and 1970s is well reflected in the selections in this anthology, which contains 48 stories representing as many writers. Most of the stories are short fiction, but some are excerpts from novels.

As Elaine Kim says in her short Preface -- "this collection celebrates many ways of being Asian American today, when the question need no longer be 'either/or'" (page xiii). (WW)

|

Top

Jessica Hagedorn, 2004

Charlie Chan Is Dead 2

Yosha Bunko scan

|

Jessica Hagedorn (editor)

Charlie Chan Is Dead 2

(At Home in the World)

[An Anthology of Contemporary Asian American Fiction]

<Revised and Updated>

New York: Penguin Books, 2004

xxxii, 576 pages, paperback

"Revised and Updated" is a bit misleading. This book is really a sequel.

Of the 48 stories in the first anthology, only 7 survive among the 42 in this one. Some writers who appeared in the first volume are represented by different stories in this one, but most of the faces are new.

Jessica Hagedorn's Introduction is shorter. What has changed since the first volume? There are many more Asian American writers than before, she says (page xxix). And judging from the considerably expanded "Personal Bibliography" at the end, I would say the variety of Asian American writers has also increased.

Hagedorn concludes her Introduction with these remarks (page xxxii).

We write out of personal and often terrifying truths. For many of us, what is personal is also political, and vice versa. We continue to assert and explore who we are as Asians, Asian Americans, and citizens of the world. Yes, we read and we write as acts of resistance and rebellion, as Vargas Llosa says. But we also read and write to remember and to dream. We read and we write to arouse the senses. To lose ourselves, to escape. To walk in someone else's shoes. To empathize and understand. We write to reflect the beauty, cruelty, harmony, and chaos of the universe; we write to inflict the pain and shock and delight of recognition. We write to elicit sympathy, fear, or maybe both.

Elaine Kim concludes her much longer Preface on a more critical note (pages xviii-xix).

The artists in this collection give us another way of looking, a different take, as they remember and create history from occluded viewpoints that challenge both the textbook and the Hollywood versions. . . .

These writers are "at home in the world" in the sense that they are not involved in an "identity" movement in search of cultural roots. At the same time, they are never quite "at home in the world" -- thus their artistic attempts to disobediently claim and articulate the "trashy heart of history."

That Hagedorn had to declare Charlie Chan dead a second time -- after insisting the first time that he was "indeed dead, never to be revived" (Hagedorn 1993:xiii) -- suggests that he may still be haunting us with his "obsequious manner, fractured English, and dainty walk" -- and with the "[a]bsudly cryptic, pseudo-Confucian sayings" (ibid., xxi) that still roll off his tongue, in still available books and films, and on numerous Internet fan sites. (WW)

|

Top

Elaine Kim, 1982

Asian American Literature

Yosha Bunko scan

|

Elaine H. Kim

Asian American Literature

(An Introduction to the Writings

and Their Social Context)

Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1982

xix, 263 pages, hardcover

Elaine Kim, a professor of ethnic studies at the University of California at Berkeley, was trained in English literature, and mostly writes about Asian American literature. For purposes of this book, has defined Asian American literature as "published creative writings in English by Americans of Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Filipino descent." She admits this definition is "problematical" (pages xi-xii).

[I]t does not encompass writers in Asia or even writers expressing the American experience in Asian languages, although I have included some discussions of Japanese, Chinese, and Korean poetry about the Asian American experience that has been translated into English. This is not to say that writings in Asian languages are unimportant to a study of Asian American literature and experience: they are simply beyond the purview of this study, and I am confident that they will be presented elsewhere. Nor have I included in this book literature about Asia written by Asian Americans in English, except when it is revealing of the Asian American consciousness.

Contents

The titles of Kim's chapters suggest how she has approached what she has qualified as Asian American literature.

1. Images of Asians in Anglo-American literature

2. From Asian to Asian American:

Early Asian Immigrant Writers

3. Sacrifice for Success:

Second-Generation Self-Portrait

4. Portraits of Chinatown

5. Japanese American Family and Community Portraits

6. Chinatown Cowboys and Warrior Women:

Searching for a New Self-Image

7. Multiple Mirrors and Many Images:

New Directions in Asian American Literature

The scope of this book reflects the political state of both the times and of Kim's own mind at time she wrote it, and her personal interest in Korean American literature. Anthologies of Asian American fiction and poetry were just beginning to appear. Maxine Hong Kingston had recently made her debut but the book world had yet heard of Amy Tan. Even the label "Asian American" was relatively new and surrounded with more controversy than today.

Images of Asians

One reason to skim through this book is to glimpse the sort of thinking that was going on at the time Kim wrote it -- some fifteen years after the start of the student movements that resulted in the creation of ethnic studies departments at UC Berkeley and other colleges. Another reason is the first chapter, "Images of Asians in Anglo-American Literature", which begins like this (page 3).

Caricatures of Asians have been part of the American popular culture for generations. The power-hungry despot, the helpless heathen, the sensuous dragon lady, the comical loyal servant, and the pudgy, de-sexed detective who talks about Confucius are all part of the standard American image of the Asian. Anglo-American writers of some literary merit have used these popular stereotypes, although usually not as a focus for their work: Chinese caricatures can be found in the pages of Bret Harte, Jack London, John Steinbeck, Frank Norris, and other writers about the American West, and even in such unlikely places as Louisa May Alcott's books for children. But, for the most part, the enormous body of Anglo-American literature containing these caricatures, particularly those dealing primarily with Asians as a theme, are of much lesser stuff -- pulp novels and dime romances of varying degrees of literary quality.

Such Asian-themed "much lesser stuff" by "Anglo-American writers" constitutes a large part of what this website is calling "Steamy East" fiction. Kim presents a reasonable overview of well-known early 20th century "pulp" novels, including those about Fu Manchu, Charlie Chan, and Mr. Moto. She contends, correctly I think, that Anglo-American literature portrays Chinese more frequently than other Asian groups. She also contends, and again I am inclined to agree, that depictions of Chinese tend to be extend to Asians generally, "particularly since Westerners traditionally found it difficult to distinguish among the East Asian nationalities" (page 4).

"Good" and "bad" Asians

Kim dichotomizes stereotypes of Asians in Anglo-American literature as follows (pages 4-5).

There are two basic kinds of stereotypes of Asians in Anglo-American literature: the "bad" Asian and the "good" Asian. The "bad" Asians are the sinister villains and brute hordes, neither of which can be controlled by the Anglos and both of which must therefore be destroyed. The "good" Asians are the helpless heathens to be saved by Anglo heroes or the loyal and lovable allies, sidekicks, and servants. In both cases, the Anglo-American portrayal of the Asian serves primarily as a foil to describe the Anglo as "not-Asian": when the Asian is heartless and treacherous, the Anglo is shown indirectly as imbued with integrity and humanity; when the Asian is a cheerful and docile inferior, he projects the Anglo's benevolence and importance. The comical, cowardly servant placates a strong and intelligent white master; the helpless heathen is saved by a benevolent white savior; the clever Chinese detective solves mysteries for the benefit of his ethical white clients and colleagues. A common thread running through these portrayals is the establishment of and emphasis on permanent and irreconcilable differences between the Chinese and the Anglo, differences that define the Anglo as superior physically, spiritually, and morally.

It is truly a delight to read what Elaine Kim writes -- however one might now and then like to demur -- because she writes with a clarity and cogency of prose that sparkles against the dull and leaden "discourse" of many of her English lit colleagues. Here I would simply point out that -- yes, both "good" and "bad" Asians in Anglo fiction tend to serve the purpose of illuminating Anglos in a superior light -- but name one racialized body of literature that does not, in general, set out to reflect better on the race represented by the writers. I would even contend that the bulk of "minority literature" also deploys majorities in roles contrived to reveal their inferiority through stereotypic faults.

Eurasian characters

Kim's remarks on portrayals of racially-mixed characters are worth noting (page 9).

When a Eurasian girl longs for freedom, she is "white at heart." When a mixed-blood boy is cruel to animals, it is because he has "inherited his callousness from his stoic Eastern blood."

Again, I would demur that the conventions of most racialized bodies of literature use extractors as exotic blends of outsiders and insiders, in order to suggest that their better, "more like us" qualities tend to descend from insiders. Witness the treatment of mixed-blood protagonists in, say, Japanese literature. Their bodies may be sexually enhanced by admixtures of white, black, or whatever physical traits, but their hearts, if they have truly human sensibilities, are Japanese.

Kim does, however, make an interesting if somewhat overgeneralized differentiation between how Eurasians are portrayed in Anglo-American literature (as one racialized body of literature), compared with literature written by mixed-ancestry authors (page 283, note 14).

. . . The literature written by writers of mixed ancestry provides a startling contrast to the portrayals of the Eurasian in Anglo-American literature. Diana Chang and Han Suyin, who grew up in China, integrate the critical struggles that occupied the people of China with Eurasian protagonists' search for identity in Frontiers of Love (New York; Random House, 1956) and A Many Splendored Thing (Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1952) respectively. . . .

. . . In contrast to the popular Anglo-American notion of Eurasian self-hatred, Chang's and Han's novels depict protagonists who do not regard their Asian heritage as a handicap. They are not particularly restless; they neither wish to be dead nor white; and they are not ashamed of China or the Chinese. No wars are waged in the veins of the type described in Anglo-American literature, although the part-Chinese protagonists are depicted as ashamed of non-Chinese who are bigoted.

This note runs nearly two pages, in a finer print than in the chapters. It is one of many notes, and one of several extended notes, that could (and should) have been incorporated into the chapters. It seems to me that Kim has no choice but to make "Eurasian" writers sit in the back of the bus -- because she herself has racialized her study as one of "images" in "Anglo-American" literature versus "portraits" in "Asian American" literature -- and "Eurasians" simply fall between her twain. (WW)

|

Top

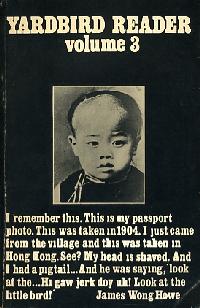

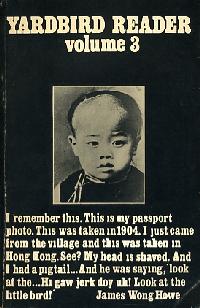

Shawn Wong and Frank Chin , 1974

Yardbird Reader, Volume III

Yosha Bunko scan

|

Shawn Wong and Frank Chin (guest editors)

Yardbird Reader, Volume III

Berkeley: Yardbird Publishing, 1974

xvi, 294 pages, paperback

Yardbird Reader, a journal dedicated to ethnic writing and some graphics, was founded by Al Young and Ishmael Reed in 1971 and annually published until 1976. Reed, the editorial director, was closely associated with Shawn Wong and Frank Chin, who guest edited Volume 3, devoted mostly to Asian American writers and their writing.

Lying about yellows never writing

Two paragraphs in Frank Chin's introductory tribute to Yardbird Publishing declare the purpose of the issue (page v).

To virtually all American yellows there's no such thing as Asian American writing. Bill Hosokawa, author of NISEI: The Quiet Americans, said in his column in the [Japanese American Citizens League newspaper] Pacific Citizen that there was no Japanese American writing.

Shawn Wong and me are taking advantage of this volume of YARDBIRD READER to print up a little proof from the past, a few years ago and right now that it is a crying damn shame to have to cut your heart out, go amnesiac, call yourself shit to your kids, lie about yellows never writing and live and lie as part of the price of acceptance in America.

The capitol of Asian American culture

The first three paragraphs of the "Introduction to Yardbird Reader #3" by Frank Chin and Shawn Hsu Wong continue to set the critical tone of the volume (page vi).

We have a friend up in Seattle that sells books. David Ishii. Go into his store down at Pioneer Square and ask him what he's got under the counter. You might come up with something real valuable. It sells for a dollar. I know the magazine is there because I sent him 25 of them. For a dollar you can buy the Special Issue on Asian America of The Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars (Fall 1972) edited by Victor and Brett DeBary Nee, Shawn Hsu Wong, and Connie Young Yu. It's the first collection of Asian American essays to reach print in America. And that was the first publication in seven generations of our being here.

The state of Washington has always been the capitol of Asian American culture. Washington gave Asian-American John Okada, pioneer novelist; Monica Sone and James Sakamoto, the founder and editor of "The American Courier," the first Japanese American English language newspaper; the Japanese American Citizen's [sic] League (JACL) was founded in Seattle. Seattle, not San Francisco, gave America the first school named after an Asian American, the late Wing Luke. The Seattle city councilman also has a Chinatown museum named in his memory.

San Francisco, meanwhile, worked hard to build a racist kennel. It was 140 years before an Asian American was appointed to San Francisco's Board of Supervisors.

The sampling of fiction and poetry in this volume is different from the sampling in Aiieeee!, which was also published in 1974. (WW)

|

Top

Marie Ann Wunsch, 1977

Walls of Jade

Yosha Bunko scan

|

Marie Ann Wunsch

Walls of Jade

(Images of Men, Women, and Family in

Second Generation Asian-American

Fiction and Autobiography)

Ann Arbor (MI): University Microfilms International, 1989 (1977)

vi, 184 pages, softcover

UMI Number 77-23,501

PhD dissertation submitted to

Department of American Studies

University of Hawaii

Doctor of Philosophy, May 1977

Marie Wunsch has taught American and multicultural literature and history at universities in Illinois, California, and Hawaii, and is now a professor in the Colleges on Line program at the University of Wisconsin College on Line . A daughter of Czechoslovakian and Croatian immigrants who settled in Pennsylvania, she lived in Hawaii for fourteen years, where she did the research for this dissertation.

Wunsch attempts to show how Asian American writers themselves have contributed to common American stereotypes about Asia and Asian America.

Abstract

A complex combination of forces from within the ethnic community and from the American social and political milieu has influenced second generation Chinese, Korean and Japanese-American writers, both in the number and kinds of works produced. The majority of Asian-American autobiographies and novels dealing with the ethnic experience and published generally between the 1940s and 1960s are the romanticized, stereotypic ones that both fit the expectations of the majority reader about Asians in America and at the same time do not threaten the delicate psychic security of the immigrant, ethnic group.

Among the most significant influences on the interpretations of personal and group experience portrayed in these works seem to be those created by the images and stereotypes about Asian [sic] in the American popular culture. Americans continue to have extensive ignorance about Asians from the immigrant periods and into the present and consequently, distorted images about the Asian-American experience.

This work undertakes an analysis of the novels and autobiographies written primarily by second generation Chinese, Korean and Japanese-American writers to illustrate that they also became a part of the complex cycle of distortion. The analysis attempts to show the patterns of these writers reflecting and interpreting, rather than recording experiences. In doing so they were conforming to the American expectations of what Asian-American family life and individual roles should [emphasis in original] be. To accomplish this analysis, the study traces the use of the images of men, women and family as they are presented in the works and how they are set against and influenced by the pervasive images and stereotypes of Asians in America.

Specific writers included for analysis of Asians in America are Jade Snow Wong, Pardee Lowe, Lin Yutang, Louis Chu, Virginia Lee, Maxine Hong Kingston, Li Ling Ai, Yonghill Kang, Monica Sone, Daniel Inouye, James Yoshida, Milton Murayama, Kazuo Miyamoto, Jon Shirota, John Okada, Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston, Margaret Harada, Shelley Ota, Daniel Okimoto, and Kathleen Tamagawa.

Wunsch was inspired to study the fictional and autobiographical stories of second-generation Asian Americans by similar studies of the literature of uprooted immigrants from Europe and their American children. Her study is thus very personal and sympathetic.

Kathleen Tamagawa (1893-1979)

While Wunsch narrates her own point of view, she does so by letting the authors of the stories she has selected speak for themselves. One of the works she twice mines for dramatic insights into the experiences of Asian Americans is Kathleen Tamagawa's Holy Prayers in a Horse's Ear (1932). Wunsch introduces Tamagawa in her chapter on "Images of the Traditional Japanese Family and Japanese-American Parents and Children" (pages 88-89).

Japanese-American writers took up this theme [of marginality] as early as 1932 with Kathleen Tamagawa's Holy Prayers in a Horse's Ear, depicting the cultural conflicts of a Japanese-Irish-American woman. Born in America of an Irish mother and a Japanese father, Tamagawa poignantly relates the ambiguities of being defined racially and culturally according to the stereotypes of the beholder. Living in both America and Japan in her early years, she experienced being insider and outsider in both cultures. Marrying an American Caucasian in 1914, in what she considered an "Eurasian marriage," she presents a frank confession about life as "an ultimate international legal absurdity." Tamagawa's early autobiography sets some patters for later works influenced by the images of Asians in the American culture.

Later in the chapter, Wunsch reveals more about the fate of the Kathleen Tamagawa's parents (pages 117-118).

Kathleen is the daughter of an unusual interracial marriage between a traditional Japanese male and a fiery, liberated Caucasian woman in the 1880s. Mr. Tamagawa . . . was sent to Chicago at age eleven for an education . . . . He spends his formative years into adulthood in America, so when he takes his family to Japan to live he embodies a strange combination of Western practicality and Eastern patience.

When his wife, Kate, full of romantic dreams of Japan out of Lafcadio Hearn and Pierre Loti wants to go native, Tamagawa "isn't going to live without a stove in the house . . . ride a rickshaw" or "play Japanese samurai," to entertain the family. Nor will he return to Tamagawa village to assume the familial duties of the oldest male. The author's portrayal of the father is less clearly drawn and remembered than that of the exceptional, dominant mother. Father Tamagawa returned to Japan as a silk merchant and remained there until his death; his wife, fearful of earthquakes, left for America with her daughter and never saw him again.

Wunsch wrote her dissertation during the first decade of the age of feminist and ethnic studies. Not surprisingly, she saves for last a chapter called "Images and Stereotypes of Japanese Men and Women". And Kathleen Tamagawa's account of her life among whites and blacks in the American south, with her white husband, dominate the last four pages. And it is Tamagawa's holy prayer that Wunsch leaves in our horse's ear (pages 155-156, bracketed clarifications and ellipses in original).

Her racial ambiguity allows even her black scrubwoman to test her by trying to bring down an uppity near-black and get an edge on another possibly threatening minority. She refuses to work in the house with "them idols [some Japanese sculptures] . . . no money gwine make me stay in the dark with those pagan ghouls." While Kate is expected to hold herself above Blacks, she feels an ironic jealousy. They have more emotional freedom because little is expected of them "by way of civilization" while she is expected to embody all the awesome culture of the entire East.

When her family finally settles in Washington, D.C., Kate is exhausted from role-playing as "a curiosity." "I knew I could not spend my life chasing other people's trains of thought and missing one train after another." She gratefully slips into the oblivion of the artificial society of the State Department wives who are "too busy gossipping about who-is-who to bother whether I was a little Japanese lady or a menace." From childhood experience and from her father's example, she learned that "polite withdrawal was one of the few responses to other people's phantasms about me." Her final thoughts, even after the exorcism of normality and literary confession, are poignantly summed as, "the unexpected, the unaccepted like myself, must remain forever outside it all."28

Thus ends a fairly credible look at some of the writings of the American "children of the uprooted" Chinese, Korean, and Japanese immigrants in America. Its major flaw in Wunsch's fashionable propensity to treat the literature she examines as evidence of "culture conflict". What Wunsch calls Kathleen Tamagawa's "cultural conflicts" (page 88) are proven by her citations at the end to be anything but cultural. True, other people in similar familial and social situations may have similar experiences, but the experiences, and how they express them in fiction or autobiography, are ultimately personal.

|

Top

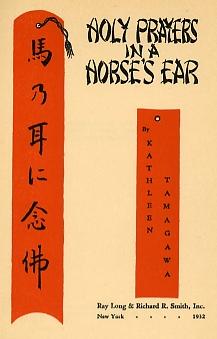

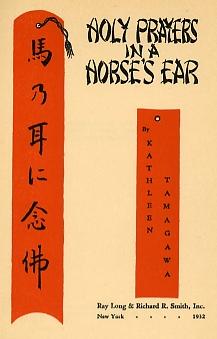

Kathleen Tamagawa, 1932

Holy Prayers in a Horses Ear

Sans expensive dust jacket

Yosha Bunko scan

|

Tile page showing proverb

Uma no mimi ni nenbutsu

which the title translates

Yosha Bunko scan

|

Holy prayers in a horse's ear

Other flaws such suggest that Wunsch was not entirely up to speed when it came to Asianesque personal names and Chinese, Korean, and Japanese expressions. The late American historian Yuji Ichioka comes out "Yugi Ichioka" in both her text and bibliography. And she seems to think that Lin Yutang's family name is "Yutang" -- a common oversight of librarians, booksellers, and bibliographers who don't expect authors who write in English to put their family name first.

The title of Holy Prayers in a Horse's Ear reflects a Japanese saying that is reproduced on the title page of book as ”n”TŽ¨‚É”O˜Å. About one-fourth into the book, Tamagawa concludes a chapter with these lines (page 75).

"Uma no mimi ni nembutsu," says the old proverb -- and it is indeed, "Holy prayers in a horse's ear."

Wunsch turns this into "una no mimi ni nembutso, and arguably she misunderstands how Tamagawa has used this proverb, to mean refusal to believe something (page 75) or hearing something one takes to be untrue (page 178). The whole point of the title is something like: "You're not going to believe this -- but it's true!"

The pleasure behind the pain

In citing mostly its darker remarks, Wunsch fails to convey the levity that makes Holy Prayers in a Horse's Ear (New York: Ray Long & Richard R. Smith, 1932) fun to read. The book begins and ends with, and is full of, humor. The last chapter is not by Tamagawa, but by her husband, Francis Reed Eldridge.

Tamagawa's book is an expansion of the statement she makes at the very outset about the nature of her existence (pages 1-2, ellipses in original).

The trouble with me is my ancestry. I really should not have been born; as a matter of fact half of my world declares I never was born. They say, that I am the non-existent daughter of my parents, that I am not their lineal descendant. No, I am not illegitimate, but just an outlawed product of a legal marriage.

Her closing remarks set up her husband's chapter, which immediately follows and ends the book (pages 258-259).

Perhaps it's wise to be foolish and foolish to be wise. But it's safer, much safer, to ride a nice, stiff, conventional wooden horse secured to a merry-go-round than a wild, untrained and untamed international steed.

For, only the non-existent can stand on their feet in mid-Pacific!

My husband who claims existence will give you his view. . . .

Let him mutter a holy prayer for the horse's ear!

Her husband wastes no time in rising to the bait (page 260).

I have the most unique wife in the world. After sixteen years of sober married existence I suddenly learn that she is only half my wife. The other half of her I am not only not married to at all, but it really doesn't exist.

Legally biscuits

He then remarks on the queer laws that account for his wife's half existence (pages 260-261).

The facts are these. My wife's father is a Japanese subject. He married my wife's mother in the United States, she being a British subject. My wife was born in the United States. That makes her an American citizen, I hear you say. True. However, she went to Japan as a minor and wishing to keep her American citizenship, registered at the American consulate in Yokohama when she became of age. I know she did, because I was the consular officer who performed that service for her. Her father, however, never registered her birth at the Japanese registration office. Therefore so far as her Japanese parentage is concerned she does not exist. Legally her father had no children in the eyes of Japanese law. Yet under American law my wife is his legal child.

They say that under international law if a cat had kittens in an oven they would legally be biscuits. . . .

This echoes Tamagawa's playful caption to a photo portrait of her with her first-born son: "My eldest son, though not unlike me, has never been a citizen of nowhere." (Plate between pages 220-221)

Wunsch and other students of "marginality" among "the children of the uprooted" must be careful not to miss the point of novels and autobiographies written by individuals with a sense of humor. While Tamagawa's life story reads a bit quaint by today's standards of narcissistic confession, it is full of the sort of levity that keeps its essential gravity humanly balanced. (WW)

|

Top

|

Hsiao-min Han, 1980

Roots and Buds

Yosha Bunko scan

|

Hsiao-min Han

Roots and Buds

(The Literature of Chinese Americans)

Ann Arbor (MI): University Microfilms International, 1989 (1980)

iv, 327 pages, softcover

UMI Number 8102737

PhD dissertation submitted to

Department of English

Brigham Young University

Doctor of Philosophy, August 1980

I am unable to trace Hsiao-min Han (possibly now Xiaomin Han) other than to this dissertation. I gather from the lack of any particular interest in women's literature, as much from the name, that the author is a "he". I also gather from the name, from the fact the author cites and translates a few passages from Chinese sources, and from certain expressions in English, that he may have been an immigrant if not a foreign student, possibly from Taiwan.

Postscript A kind reader directed me to a web profile of Hsiao-min (Sherman) Han. Han came to the United States from Taiwan in 1974, the year after he received a bachelor's degree from Tamkang University. He is now a professor of English and Chinese literature at Brigham Young University, Hawaii. His specialities include "Asian American literature, English Romanticism/Victorianism, and classical Chinese fiction." (BYU Hawaii website)

As dissertations go, this one is pretty much plain vanilla. Its most remarkable feature is Han's classification of Chinese American writers.

Abstract

The literature of Chinese Americans has never drawn any serious attention from the American public since the 1850's when the earliest Chinese immigrants arrived in this country. This dissertation discusses this literature by dividing it into four major groups: the early immigrants, the sojourners, the Chinatown writers, and the intelligentsia. With the exception of the first group, which contains works in Chinese, all the other literary works are in English.

In the discussions of each groups, there are detailed introductions of the historical backgrounds and literary characteristics, as well as critical interpretations of the important works of the major genres. Since the aesthetic value in this literature is as significant as its sociological value, this paper focuses on the analysis of both Chinese-American ethnic experiences and the literary qualities of the works.

Han elaborates on his classification scheme as follows (page 15).

The immigrant group covers the period from the 1850's to the 1930's, when the second generation of Chinese-Americans started to speak for themselves in English. Some sojourner writers and Chinatowns [sic] authors began to write during World War II, while the naturalized intelligentsia did not produce any serious works until the 1950's, a decade after the war. But the time period for the last three groups often overlaps.

Chinese culture and ethnic pride

Han imputes four characteristics to sojourner literature: (1) presentation of Chinese culture, (2) ethnic pride, (3) reflection of the mood of Chinese literature, and (4) elegant English.

Sojourners "usually had a good education in China before they came to the United States to pursue advanced degrees" (page 123), Han writes. And, in his view, no one exceeded Lin Yu-tang (1895-1976) when it came to presenting Chinese culture out of a sense of ethnic pride (pages 124-125).

Lin Yu-tang's Chinatown Family is probably one of the best illustrations of the ethnic pride of the sojourner writers. The members of the family in the novel, though they had received little education in China, are very proud of their Chinese heritage. Tom Fong, Sr., the father of the house, asks his sons and daughter to read the Confucian Four Books because he knows that "there is very good teaching in them."18 He wants them to understand the greatness of Chinese civilization and to be proud of their heritage while going to school in the United States.

The children are expected to practice moral integrity in the home regarding their family relations, and they are supposed to extend their sense of moral integrity to social circles outside the family (page 125). But, as Han goes on to tell us (page 126), "In general, the author [Lin Yu-tang] deliberately ignores the description of the dark side of the Chinatown which includes organized crime, prostitution, opium eaters, etc."

Reflections of Chinese literature

The third characteristic of sojourner literature is "reflection of the mood of Chinese literature" -- meaning that "To the reader who has some background in both English and Chinese literatures, the literary works of the sojourner writers seem to be closer to the latter than to the former despite the fact that they are written in English" (page 133). Narrative styles, literary subjects, and other story aspects are "in many ways similar to those of the mother culture" (page 134).

Chinese expressions may simply be transliterated into the alphabet for the benefit of those who recognize their meaning, though they could just as well be translated -- or might be literally translated into English -- again, mostly for the benefit of readers who know that "wash dust" means "a reception dinner", "bad eggs" and "seeds of sin" are "rascals", and "killing a chicken as a warning to the monkey" alludes to "a well-known Chinese fable which teachers the effective way of education" (page 136).

The fourth and last characteristic of sojourner writers is, Han says, "their elegant English" (page 140). They do not write in pidgin. They have a have mastered "formal and correct English" (page 140) and their diction is "accurate and appropriate" (page 141).

Elaine Kim on Lin Yutang

"Chinatown writers" tend to write in more idiomatic and blunt English as they get down and literally "dirty" about their experiences of discrimination in America (page 224) -- whereas Chinese-American intelligentsia are more inclined toward a passionate "decadent romanticism" that admires "sensuality, emotion, and nature" (page 241).

Han's approach is thus more formalistic than Elaine Kim's in, for example, Asian American Literature (1982), in that he attempts to differentiate works of Chinese American literature according to how they are structured and written -- while she is critically more concerned with the social and psychological implications of stories. Kim, for example, analyzes Chinatown Family as a "portrait of Chinatown" -- and says nothing about Lin Yutang (her spelling) in terms of how elegant his English may have been (pages 104-106). And she runs circles around Han when it comes to her perceptions of Lin as a writer (Kim 1982:105-106).

Chinatown Family is a highly idealized portrait in which the familiar stereotypes of Chinese abound. Conflict is absent from the story because Lin does not really consider a laundryman's life significant enough to be dealt with seriously. His apparent boredom with the subject explains why the portrait is broken by narrations and lectures on the Chinese rotating credit system, American jazz, and traditional Chinese philosophy. Even the dialogue between the laundryman's son and the Chinese refugee are but recitations of classical Chinese verses.

While Han sees in Lin merely the "ethnic pride" of a highly literate sojourner who is compelled to present elements of Chinese culture, in elegant English that to some extent reflects Chinese literature, Kim sees in him a snobbishness that lacks true interest in, and empathy for, ordinary Chinatown denizens. (WW)

|

Top

Xiao-huang Yin, 2000

Chinese American Literature

since the 1850s

Yosha Bunko scan

|

Xiao-huang Yin

Chinese American Literature since the 1850s

Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2000

xiv, 307 pages, hardcover

Xiao-huang Yin, who left China in 1985, has specialized in Asian American studies since earning his doctorate at Harvard in 1991. Now a professor in the American Studies Program at Occidental College, his courses have included "Asian Immigrants in American Society" and "Cultural Revolution in China".

Contents

This book is essentially a rewrite of Yin's doctoral dissertation on "the sociohistorical context of early Chinese American writing", expanded to include "contemporary Chinese American literature and publications by Chinese immigrants in their native language." The contents of his revised and enlarged study looks like this.

1. Plea and Protest: The Voices of Early Chinese Immigrants

2. The writing of "Cultivated Chinese":

Improving an Image to Win Sympathy and Acceptance

3. The Voice of a Eurasian: Sui Sin Far and Her Writing

4. Seeking a Place in American Life:

The Autobiographical Writing of Second-Generation Chinese

5. What's in a Name: Chinese-Language Literature in America

6. Immigration Blues: Themes and Subject Matter in

Chinese-Language Literature since the 1960s

7. Multiple Voices and the "War of Words":

Contemporary Chinese American Literature

Sui Sin Far on prejudice

Chapter 3 is a superior overview of Sui Sin Far, the pen name of Edith Maude Eaton (1865-1914), who he calls "the first Chinese woman writer in North America" when he introduces her -- though later he mostly labels her a "Chinese American" author. He praises Sui for not being afraid to confront the prejudice within Chinese and Chinese American society (page 108).

Compared to their bias against the "half white," Chinese prejudice against the "half-black" was even stronger.62 The tragedy of Arlee Hen (1893-1985), the daughter of a Chinese father and a black mother, in Mississippi is one example. Although she was proud of her Chinese heritage and insisted that she "never did feel any difference from Chinese," she was not accepted by the local Chinese community during her lifetime. Even after death, her wish to be buried beside her Chinese husband was denied on the ground that the local Chinese cemetery was for "pure-blooded" Chinese only.63 Such misplaced superiority made Sui muse, "Fundamentally, all people are the same. My mother's race is as prejudiced as my father's. Only when the whole world becomes as one family will human beings be able to see clearly and distinctly" ("Leaves" 129).

Yin's notes, drawing from books and monographs on Chinese in Mississippi, observes that "Between 20 and 30 percent of the Chinese who lived in Mississippi married black women before 1940 (page 116, note 62). Moreover, "prejudice [against racially mixed people] is not confined to Chinese. . . . as Werner Sollars points out . . . 'racial thinking typically only accepted "pure" races and looked at mixtures with particular suspicion and contempt' (ibid., note 63).

Frank Chin and Maxine Kingston

The final chapter puts a suitably critical finish on Yin's study. It would not serve the truth to review "Contemporary Chinese American Literature" without examining the dissent that divides readers over questions about the authenticity of the voice of Asian American fiction that makes it to the top of New York Times bestseller lists. The sharpest critic is Frank Chin, and his favorite target is Maxine Hong Kingston (page 235).

Because the most vociferous critic has been Frank Chin, the controversy has been labeled as a "war of words" between Kwan Kung and Fa Mulan, two icons appropriated by Chin and Kingston to represent, respectively, Chinese American men and women.21 Protesting what he considers an attempt to feminize Chinese American literature, Chin accuses Kingston of being a "yellow agent of the stereotype" and calls her (as well as several other prominent Chinese women writers, including Jade Snow Wong and Amy Tan) an enemy. In his opinion, they demonstrate a vested interest in casting Chinese men in the worst possible light and have perpetuated the stereotype of a misogynistic, and therefore inferior, Chinese society. Such practices, Chin believes, spring from intentions to promote their work at the expense of Chinese men. For that reason, he warns, "I have no advice for young yellow writers, only a warning and a promise: as long as I live, if you fake it, I will name you and your fake tradition."22

Yin casts only a few votes for Chin. He prefers to see the misogyny some female authors impute to Chinese culture as more complex than it appears. He would rather view male and female status among Chinese from a sociohistorical perspective, and explain the variety of relationships between the sexes in terms of class than gender.

Yin also takes exception to Chin's view of why writers like Wong, Kingston, and Tan have been popular (pages 238-239).

Chin's allegation that the popularity of Chinese women writers is exploited by mainstream readers, especially by rapacious and uncouth white men, seems to lack credence.46 One measure of its validity can be challenged by the success of Chinese immigrant women writers who publish in Chinese. Their work is read by people of their own race rather than by white men, but many are well received and more popular than their male counterparts.47 In reality, it is the rise of women's consciousness and the increased interest in (and appreciation of) cultural pluralism and diversity in American society that have inspired more Chinese American women than men to pursue literary careers and find popular success.

Yin fails to comment on whether the stories that Chinese immigrant women write in Chinese for consumption among readers of Chinese are like those written by American writers like Kingston and Tan for readers of English. He also seems to take for granted that native readers of Chinese (mostly people who are racially "Chinese" and nationals of China), and native readers of English (most racially white nationals of the United States, Canada, and other such countries), expect to read, and find satisfying, the same sort of stories.

Multidimensioned sensibility

In all fairness to Yin, he has does an excellent job presenting the many sides that people have taken regarding Chin's intentionally provocative views. Yin marshals some very heavy artillery against Chin, but he stops short of entirely endorsing the views of his detractors, and points out that Chin has been equally critical of a number of male writers, has included some female writers in a well-known anthology he coedited, and has some fans among Asian women writers (page 240).

In the final two pages of his book, Yin stands back and takes a broader view of the Chin-Kingston feud (pages 245-246).

The effort to define a Chinese American literary sensibility is neither easy nor simple, and the controversy over standards, however unpleasant, symbolizes the highly polarized and vastly diversified contemporary Chinese American experience. . . .

Finally, although the war of words may have weakened the strength of Chinese American writers as spokespersons for the community, it is also a sign of the maturing of Chinese American literature. Because the conflict has been drawn on the basis of individual views and personal interests rather than along a rigid gender or class line or as an attempt to follow fashions in mainstream society, the division represents a more diversified and balanced opinion of Chinese Americans in terms of the authenticity, representation, and creativity of their writing. In this sense, the controversy represents a multidimensioned Chinese American sensibility and demonstrates that the literature has finally come of age and become an organic part of the Chinese American experience.

Peace. (WW)

|

Top

|