The Steamy East

Steamy East exotica

By William Wetherall

First posted circa 2005

Last updated 28 July 2024

Exotica in Steamy East and related fiction Gazing at and projecting on the unfamiliar

Exotica in Steamy East and related fiction

Gazing at and projecting on the unfamiliar

The lure of vicarious adventure

By William Wetherall

All stories, true or fictional, are vehicles for doing things, including travel, in our heads instead of actually. Through stories heard recited by a village elder, or read in the privacy of our imagination while strap-hanging on a packed subway, we travel within our own world or to distant lands on this planet or to galaxies in another universes, in the present, to the past, or into the future, in reality or in fantasy. We suspend ourselves in such dreamlike moments without much thought as to whether what we are hearing or reading is true.

In the midst of a story, or as an afterthought in a more sober moment, we may frown or laugh at something that strikes us as too far-fetched to be true -- no matter how much we will ourselves to believe everything. Or in the light of later experience, we may realize that something we accepted as true is anything but.

Steamy East stories are full of descriptions of places and peoples the reader, and often the writer, has never been to or seen. Because they are fiction, they should be read as though every word were a lie intended merely to entertain. Many stories, though, are also told to educate or even enlighten. In addition to being an entertainer, the writer is also some mixture of tour guide, teacher, professor, counsellor, philosopher, politician, publicist, philosopher, brain washer and pimp.

Story tellers are by nature manipulative. In order for their stories to have any effect whatever, they must manipulate human feelings. Only by playing with our emotions can they make us laugh or cry, forgive or be angry, believe or question, love or hate, or want something or want to do something as a consequence of the story.

One of the most easily manipulated feelings is curiosity about things unfamiliar, human and otherwise. If you see someone who looks different, you look. If you see someone eating something you've never seen, or eating something you've seen but never eaten, or eaten but in a different way, you look.

Steamy East novels are typically full of descriptions of local life. Details about history and food and customs are welcome if they are dramatic -- if they contribute to the story by building ambiance related to the plot. Often, though, details about local life are gratuitous -- thrown in for their own sake, not because they develop the story.

At best, details about places and peoples are correct. At worst they are incorrect. At best, errors are hilarious. At worst, they are blatantly offensive.

Misinformation

Here we will sample all kinds of misinformation in Steamy East fiction. Some examples reflect the efforts of good writers who simply didn't have their facts right. Others exemplify the tendency of vicarious travel hacks to masturbate while writing about things they themselves find irresistibly exotic.

My favorite recent example is a terribly exciting but horribly written "romance suspense" by Jessica Hall called The Kissing Blades (Signet, 2003). Hall interlaces her commonplace "missing sword" mystery (the "suspense") with a couple of explicit sex scenes (the "romance"). She also takes every opportunity to exotify the "Japanese" and "Chinese" elements in the story, which is set in California.

Behavior

[Forthcoming]

Harakiri

"And you said this sword is Japanese, right? How did you know that?"

"I'm Japanese."

"Your people like to do some pretty gruesome stuff with swords, don't they? Like that hara-kiri thing, right?"

"It's called seppuku, it's a form of ritual suicide, and my people stopped doing it about five hundred years ago."

-- Jessica Hall, The Kissing Blades, 2003, page 21

See also Steamed rice and snot.

Clothing and dress

[Forthcoming]

Kimono

[Forthcoming]

Qipao, cheongsam

[Forthcoming]

Customs

[Forthcoming]

Flower arrangement

[Forthcoming]

Tea ceremony

[Forthcoming]

Food and drink

[Forthcoming]

Dog meat

[Forthcoming]

Monkey brains

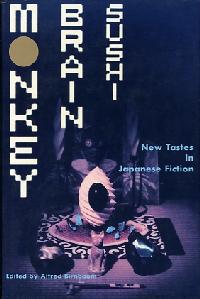

Alfred Birnbaum This is not a review of this book, an anthology of ten short stories and one graphic novella, translated from Japanese by Alfred Birnbaum and three others. It is a commentary on how fiction from Asia is often presented to readers outside the region as exotic. By the time this anthology came out, Birnbaum had made a name for himself as Kodansha's house translator of Murakami Haruki novels like Wild Sheep Chase, which made Murakami the darling of New York sushi bravers and the hottest Japanese literary property ever to reach English shores. What many readers of English have been led to believe is "vintage Murakami", though, turns out to be Birnbaum's jazzed-up revampings of Murakami's simpler, more powerful prose. Here is how Burnbaum introduces the Monkey Brain Sushi stories (page 4). Neither ponderous tomes nor throwaway pulp, this is popular writing fresh from the cultural chopping block. At once haute and irreverent, Japanese writers today are serving up slices of verbal sushi that bite back. Here at last we find sharply honed wit in the face of everyday nonsense, human comedy for the information age -- the dazed adventures of the post-Zen "monkey mind" as it leaps from channel to channel toward a future that looks suspiciously like your favorite late-night rerun. Birnbaum publicizes the anthology like a freak show barker. In front of readers he must think view sushi as the ultimate oriental adventure, he chops up monkey brains so raw they snap back. Never mind that Hollywood associates monkey brains with southeast Asia or China. Not even fish, quick or dead, figure in the interesting but not so otherworldly or shocking stories in this book. (WW) |

Natto

"Natto is fermented soybeans. It smells to high heaven, and looks like acorns laced with snot." She shuddered.

-- Jessica Hall, The Kissing Blades, 2003, page 141

See also Steamed rice and snot.

Rice

Sean paused to study the racks of roast duck displayed in a food market window. Beneath them, customers sorted through open bins of imported specialty vegtables and mushrooms, and selected huge sacks of gohan and natural rice. Further back were the livestock cages. "I can't imagine the appeal of watching your food swim, skitter, or cluck before you eat it."

-- Jessica Hall, The Kissing Blades, 2003, page 159

See also Steamed rice and snot.

Sake

[Forthcoming]

Sushi / sashimi

[Forthcoming]

Tea

[Forthcoming]

Language

[Forthcoming]

Hanzi, hanja, kanji

[Forthcoming]

Minorities

It is hard to find a potboiler, written in English and set anywhere in Asia, that does not trot out one or more real or imagined minority, usually in what amounts to a gratuitous "cameo" appearance. Some stories read as though the writer had been working off a list of "must include" topics contrived to make the story seem "concerned" and "sensitive" -- and otherwise "relevant" to the times.

When reading Steamy East fiction, one should never take the social factuality of any character for granted. Minorities are apt to be described in ways that bear no resemblance to minorities in real life. Most are there only because the writer (or possibly an editor) thinks salting a story with minorities will improve its social flavor.

I have not done a count, but "burakumin" seem more likely than other putative minorities to pop up in fiction set in Japan, past or present. The irony is, outcastes ceased to exist in 1871, and even before that they were not called "burakumin" -- hence the quotation marks.

Ainu

"Chief, I want an extra two knots for a hundred miles to Cape Byron. Can you do it?"

"No."

Those in control cringed. The planesmen grew more interested in their dials. The engineer was part Ainu, from Hokkaido, so that his insolence toward superiors was to be expected, but he was pushing his luck. Osu ignored it, too preoccupied with the loss of an hour due to the encounter with the convoy, and the danger if he had to wait out the daylight hours in enemy waters.

-- Ian Slater, MacArthur Must Die, 1994, page 110

See also MacArthur should have died.

Burakumin

Read any novel written in English and set in Japan, and somewhere in the story -- usually sooner than later -- you are likely to encounter the word "Burakumin" -- probably with an upper-case "B" but possibly all lower case, and maybe in italics, or perhaps enclosed in quotation marks. Most likely the story has absolutely nothing to do with with alleged "people", but the author feels compelled to mention them in passing, usually to make a point about "Japan" and "the Japanese" being unkind to ethnic and racial minorities -- and depending on who you read, "burakumin" are one, the other, or neither. Whatever they are, they are typically caleld "descendants of former out-castes", and they are supposed to number as many as 3,000,000 million

Michael Crichton, in Rising Sun (1992), which is set in Los Angeles, features a Japanese graduate student named Theresa Asakuma. who he contrives as quadruple victim of discrimination in Japan -- she's a woman, she's of mixed blood, her father was black, and her mother was a Burakumin. And through her mouth, he alleges that "In Japan, the land where everyone is supposedly equal, no one speaks of burakumin" (intriple victim of discrimination in Japan -- Rising Son

As though to vindicate this claim, Hayakawa Shobō, the publisher of the Japanese translation, which had published at least 15 of Crichton's earlier novels, asked Crichton for permission to delete this entire sentence, and all other mentions and details about burakumin from the translation, and Crichton consented. Was he admitting that the statement was incorrect? Or was he putting the income he stood to receive in royalties ahead of the truth?

The truth of the matter is that "burakumin", once a fairly popular word among residents of former outcaste neighborhoods, is now a word that "buraku liberation" activists in Japan no longer like -- for two reasons. First, when used to label an individual, it marks the individual as somehow different from the mainstream Japanese population -- when in fact there are no legal, social, or cultural criteria for differentiting people who may have descended from yesteryear's outcastes from the mainstream. Second, the Buraku Liberation League (Buraku kaihō dōmei πϊ―Ώ), which has cells in a number of former outcaste neighborhoods, invests its political interests in the neighborhood -- i.e., in the "buraku" -- as a territory that continues to be stigmatized in the minds of some people as a former outcaste settlement.

Ergo, anyone now residing in such a neighborhood -- regardless of the person's family history -- might someday encounter -- somewhere in Japan if not abroad -- someone who, knowing where the person lives or used ot live, considers the person undesireable as an employee or spouse. BLL calls this "buraku discrimination" (buraku sabetsu ·Κ)-- i.e., discrimination against people on account of their residence in a place BLL regards as a "discimination-receiving buraku" (hi-sabetsu buraku ν·Κ) or "unliberated buraku" (’Jϊ). "Buraku discrimination" therefore boils down to "residential discrimination" -- and everyone who now lives in, or has lived in, or may live in a "buraku" -- a former outcaste neighborhood -- is potentially subject to such discrimination as a "buraku resident" (buraku jūmin Z―).

"Burakumin" as a label for "people" (min ―) of a "buraku" () would differentiate individuals on account of their ancestral blood links with outcastes emancipated in 1871. This should not happen. Having been relieved of the "status discrimination" (mibun sabetsu gͺ·Κ) that defined them prior to 1871, they should not be branded with another label that engenders status discrimination. Nationals (kokumin ―) in Japan come in one type only. The status of being a "national" is differented by sex (seibetsu «Κ) and age (nenrei betsu NίΚ) -- and also by marital status, and whether one is a legal resident of Japan. But family origin is no longer a cause for an exceptional status within the general population. Family origin matters only within the Imperial Family, which is subject to its own family law, which preserves what is left of the stem family as the last fortress of caste discrimination in Japan.

Chosenese, Koreans, Choreans

Forthcoming.

Gaikokujin, gaijin

Forthcoming.

Konketsuji, haafu

Forthcoming.

Money

5-yen coins

[Forthcoming]

See also Barbarian Geisha.

Occupations

[Forthcoming]

Geisha

[Forthcoming]

Samurai, ronin

[Forthcoming]

Yakuza

[Forthcoming]

People

[Forthcoming]