The geisha who shagged me

By Mark Schreiber

A version of this review appeared as"A textbook tale, lacking in Eastern promise" in

Mainichi Daily News, 14 August 1999, page 9

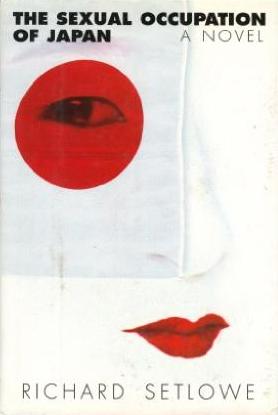

Richard Setlowe Just over a century ago, American lawyer John Luther Long published a romantic novella in Century magazine entitled "Madame Butterfly." The pathetic tale, of an abandoned Japanese woman pining away for her Western lover, is believed to have been derived from French naval officer Pierre Loti's autobiographical novel "Madame Chyrysantheme" published a decade previously. Working in collaboration with David Belasco, Long produced a version of Butterfly for the London Stage in 1900. Seated in the audience one night was an Italian opera composer named Giacomo Puccini, and you know the rest. Perhaps we should be thankful for the prudishness of those times, or who knows, Mr. Puccini might have entitled his opera something even more offensive than "The Sexual Occupation of Japan." Fortunately for the publishing industry, today's truth-in-labeling laws do not appear to extend to book titles, or the author of the work under review might find himself facing litigation. Despite the suggestion in its title of steamy romance or at least a lively pillowing or two, this book has little sex and none titillating enough to justify its title. It would have been more honest -- and certainly far more accurate -- to entitle this book "The Sexual Preoccupation with Japan." In the narrative, American showbiz attorney Peter Saxon wings his way to Narita. His mission, as he puts it, is "to put together the first Japanese-American keiretsu." Invited by his hosts to recover from jet lag by partaking the usual perks associated with such junkets, he is entertained at a night club and encouraged to take out one of its hostesses for . . . whatever. Later, amidst an unlikely set of circumstances, Saxon unexpectedly encounters the lovely Lilli, the Japanese Dietrich with whom he had become passionately intimate during his salad days with the U.S. Navy. Yet over a span of 309 pages, our ever-cautious attorney never once pillows in the present tense. The few accounts of Saxon's cavorting appear as flashbacks of events from three decades ago, when he sowed his wild oats while on leave from the Vietnam war. Telling his story in the first person, Saxon describes what occurred then as "ghosts . . . banished for so long . . . exiled back to the Far East because they had no part in my life home in America." Since the author fails to dispense any literary Viagra to resuscitate these old ghosts, action in the present remains flaccid. But lack of sex aside, the story has little else to recommend it. The author appears to have divided his research between the paperback book carousels in his local supermarket and video rental shop, to see what others in this genre have done. He then tosses their contents into a blender and, if you'll excuse the mixed metaphor, starts boiling the Japanese pot. This strategy leaves the reader with the story of an American lawyer who visits Japan on a business trip, and, through a poorly contrived series of coincidences, encounters the same people with whom he had spent his shore liberty back in the 1960s. Meanwhile, practically every Japanese male he confronts -- from an MITI official to a pair of yakuza assassins -- is either inscrutable, sinister, or out to do him harm. The result is a notably derivative work. Michael Crichton's "Rising Sun" was the first model that comes to mind, as "Occupation" also features such familiar plot treatments as 1) a beautiful girl of mixed Japanese and black parentage, who voices her bitterness over the racial discrimination meted out by her compatriots; 2) Japanese and Americans locking horns during corporate takeover negotiations; and 3) government and police efforts to cover up a string of murderous assaults. One can also catch glimpses of other literary influences from Trevenian ("Shibumi"); Clavell ("Shogun"); and even Lustbader ("The Ninja"). And with shades of James A. Michener ("The Bridges at Toko-ri," "Sayonara"), we're provided with flashbacks of young gung-ho U.S. pilots enjoying their fill of Japan (or Japanese women) before flying off to strafe the Reds. Its implausible story notwithstanding, the book is not without other problems. The mayor of Nagasaki was shot by an ultranationalist in 1990, not 1989 as the author puts it. And while dispensing with his obligatory snippets of Japanese history, the author was off on some of his dates by several hundred years. For instance, he describes the walls of Tokyo's imperial palace as dating from the fifteenth century, when in fact they were built well into the seventeenth. So let that be a lesson you aspiring authors out there: Don't doze off during your Hato Bus Morning City tour. Nor was the level of proofreading up to the standard expected of a major publisher. Tea-master Sen-no-Rikkyu's famous aphorism "Ichigo-ichie" is repeatedly misspelled "inchigo." The author, or his editor, also gets a failing grade in French, having rendered "objets d'art" as "objects" with a superfluous "c." Typos and errors aside, this work's main flaw can be diagnosed to an ailment that remains endemic in contemporary mainstream fiction set in Asia. Publishers, and unfortunately their audiences, continue to show a preference for the same worn-out cliches, two-dimensional character portrayals, dependence on exotic or irrelevant cultural accouterments and racial stereotyping. Sexual or not, Japan continues to suffer from an occupation of literary mediocrity. |