|

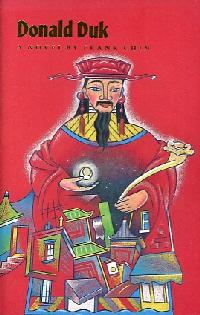

Frank Chin

Donald Duk

Minneapolis: Coffee House Press, 1991

173 pages, paperback

I consider Donald Duk the best of Frank Chin's longer parodies. Not only is it written in clear, simple prose, but it also works fairly well structurally.

The story is a about an eleven-going-on-twelve-year-old boy, in San Francisco's Chinatown, who is rebelling against both what his white teachers and classmates say about things Chinese, and what his parents and other Chinatown denizens do and say in the name of being Chinese. It would have been better, however, if Chin had made a greater effort to tell it more through the boy's eyes, and less from his own too predictable point of view.

108 outlaw heroes

Donald Duk hates his name and tells no one at school that he is taking tap dance lessons because his mother, Daisy Duk, likes Fred Astaire. His mother helps his father, King Duk, build model airplanes, from balsa wood and paper, each representing one of the 108 outlaw heroes of The Water Margin. Venus and Penelope, his fourteen-year-old twin sisters, who also make planes, never pass up an opportunity to remind Donald that they, for the moment, are bigger and smarter than he is.

Enter Donald's classmate and friend, a white boy named Arnold Azalea, who sometimes embarrasses Donald because he professes to like Chinese food, wants to know everything about the coming Chinese New Year, and especially wants to learn all about the model planes and the 108 outlaws.

Chinese Fred Astaire

Donald goes to his dancing lesson on the first day of the first month of the new year, forgetting that there is no lesson on that day, and finds his teacher getting ready to dance flamenco with a Cantonese opera musician who plays Spanish gypsy guitar, and a woman in a shawl who claps hands like snapping twigs. Donald, who is invited to stay and watch, wonders why Larry Louie, his teacher, is dancing flamenco (page 52).

"Out of respect," Larry Louie says. Mr. Doong still plays. Larry Louie moves his arms and hands to the guitar as he talks. "Back in the fifties, after that Korean War, some of us thought about being a minority race. Now, the gypsies in Spain can be called an oppressed minority race. But the gypsies are not living their lives, laying their deaths or making their music on the doorstep of their oppressors. All the white people in Spain could die right now, and the flamenco would still be flamenco. The gypsies still gypsies. You can hear and feel the integrity in their music. I love it, don't you, Mr. Doong?" Mr. Doong's reply is a flurry of tinkly glassy notes and explosions of jackhammered chords.

Familiar voice

Readers familiar with Frank Chin's "voice" will immediately recognize that he has made a cameo appearance in the guise of Larry Louie, as the flamenco story is one his favorites. In "Come All Ye Asian American Writers of the Real and the Fake" (Jeffery Paul Chan et al., editors, The Big Aiiieeeee!, New York: Meridian Books, 1991, pages 1-92), published the same year as Donald Duk, Chin wrote practically the same thing (page 2).

If all the white Spaniards were to disappear off the face of Spain right now, the gypsies and flamenco would not lose anything that holds them together. The gypsies would still be gypsy, and the flamenco would be flamenco. The only difference would be that they would have more room to grow.

Chin puts similar words into Larry Louie's mouth, and Donald Duk's ears, for the same reason: to cause readers to wonder what would remain of "Chinese Americans" if there were no whites to define "Chinese" in America. Yet the repetition of such patently boilerplate commentary, in a novel ostensibly about the coming of age of a young boy, gives the impression that Chin is either too obsessed with chasing the same old dragons with the same old axes, or is simply lazy when it comes to creating newer and fresher material.

A little white racist

Donald's dad takes Donald to a herb doctor, who thinks Donald is skinny for an eleven year old (pages 89-90).

"He's acting strange," Dad says. "He's jumpy and jittery, tapping his toes and clicking his heels all the time like someone with a palsy."

"Hmmm," the herb doctor says. "Your other hand, please, boy."

"And he steals from me and lies, and treats Chinese like dirt."

"I do not!"

"I think I may have accidentally taken home a white boy from the hospital and raised him as my own son. And my real son is somewhere unhappy in a huge mansion of some old-time San Francisco money."

"Stick out your tongue," the herb doctor says. Donald Duk sticks his tongue out. The herb doctor plays a flashlight on it and reads Donald Duk's tongue.

"I can't believe I have raised a little white racist. he doesn't think Chinatown is America. I will tell you one thing, young fella, Chinatown is America. Only in America can you run to any phone book, any town, look under C and L and W and find somebody to help you," Dad says. Donald Duk doesn't laugh. "He doesn't understand a Chinatown joke either," Dad says.

Donald's dad is referring to the fact that Donald had taken one of his model planes down from the ceiling at night, sent it flying up Grant Street where it caught fire and crashed, and then lied about it.

Eating pets

Arnold is a foil for explaining things about Chinatown life that ordinarily wouldn't need to be explained between people who live there. In one scene, Donald and Arnold, and Donald's parents and sisters, and a friend of the fathers named Uncle Donald Duk, are at a live fish store when a load of giant clams comes in (page 39).

They have large shells, the size and shape of a small loaf of French bread. A round thick tube of flesh sticks out of the shell. "Ugh! Obscene!" Donald Duk says.

"What are they?" Arnold can't believe his eyes.

"Mmmmm! Jerng putt fong!" Venus yelps.

"Daddy! Get some for the banquet tonight!" Penelope picks up the yelp where Venus leaves off.

"No!" Dad says.

"Please, Daddy," Venus says.

"We're not supposed to eat red meat, right?" Penelope gushes wide-eyed. "And jerng putt fong is not red meat."

"Too common! A banquet is a banquet because all the food is special, not common nothing ordinary."

"Good," Donald Duk says. "I want a filet mignon wrapped in bacon, with . . ."

Donald Duk is cut off by Dad, "No. Beef is common! It used to pull wagons and plows. No. We don't eat work animals tonight."

"We eat pets!" Uncle Donald Duk says, and Mom and twins laugh, and all slap Uncle Donald Duk's sleeve.

"Uncle Donald!" Mom scolds. "We do not! What will Donald's friend Arnold think?"

We get along with them fine

As the story builds to a climax, in a scene toward the end, where the family is eating breakfast in a booth at Uncle's Cafe on Clay, on the fifteenth day of the new year, Donald declares he's not going to school (pages 149-150).

"What do you mean, you're not gong to school today?" Mom asks.

"They're nothing but stupid racists there . . ."

"Oh, Donald Duk!" Venus says.

"Hold it, girls. let him talk," Dad says.

"I was just going to ask if there are any old-fashioned, insensitive, machismo, chauvinist pigs there too," Penny says.

"Misogynists, in other words," Venus says.

"Hold it, girls let him talk," Dad says.

"They're a little snooty maybe," Mom says. "But you know, you can be a snob and not be a racist."

"And vice versa too, Mom," Venus says.

"Or you can be both! Let's be fair, Mom," Penny says.

"That's what I'm trying to say!" Donald says.

"I don't care if they are snooty racists. You're going to school. Do you know how much it costs per day to send you to that school? You're going to school."

"They don't like Chinese . . ."

"Since when did you like Chinese?" Venus asks.

Tell them they don't like Chinese, not me. I have no problem with Chinese people. You're going to school."

"What's wrong with racists, anyway?" Mom asks. "We have been living with them for over a hundred years now, and we get along with them fine."

"They're supposed to be my friend," Donald Duk says.

"No, they're not," Dad says.

"What about Arnold?" Donald Duk asks.

"What about him?" Dad asks without raising his voice, without missing a beat. "You don't go to school to make friends."

"Ah-King, don't upset him anymore than he already is."

"Is he a racist too?" Dad asks.

"No, he's more interested in the Chinese than Donald even," Venus says.

"Who asked you?" Donald snaps.

"I just want to know for my information," Dad says. "The only reason we let him stay in our house and are so nice to him is because he's your friend, not ours. And if he's a racist and not your friend, we should know. And if he is your friend, you should go back to school and back him up. But you're going to school to learn something, no matter what."

A four-star family sitcom

Chin weaves lots of good stories into Donald Duk, and most of them contribute to the suspense that dramatically resolves in some rather moving scenes at the end, including one in which Donald Duk corrects his teacher, Mr. Meanwright, on an important point of Chinese American history in the building of the first railroad across the Sierra Nevadas.

I would give the story five stars, instead of only four, if Chin had made a greater effort to get out of his own skin, and into the skins of his generally interesting and plausible teen and adult characters.

Donald Duk has the dramatic feel of a good family sitcom that would have been more effective as social parody had there been less social commentary. All of the characters, including Donald Duk and his sisters, and Arnold, would have benefited from more development. (WW)

|