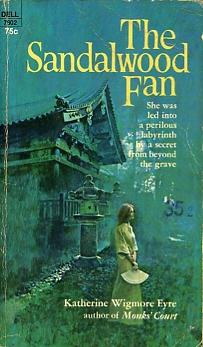

Katherine Wigmore Eyre

The Sandalwood Fan

New York: Dell, 1970 (1968)

222 pages, paperback

Katherine Eyre (1901-1970), who is all but forgotten today, wrote mostly stories for young boys and girls, but she also authored several romantic suspense novels. The Sandalwood Fan, a somewhat gothic mystery set in San Francisco and Hawaii in the 1950s, seems to have been her last. The mysterious fan holds the key to the heroine's fate, as does the strange box in The Chinese Box (1959), also set in Eyre's native San Francisco.

Lovely young Nan

The blurb on the fly invites readers to take the plunge.

FLIGHT INTO FEAR

Home for lovely young Nan Allen was always the gloomy San Francisco mansion where she had spent her orphaned childhood, watched over by the faithful family servant, Ah Sam.

Then Ah Sam died, leaving to Nan only a delicate Oriental fan. Lost, adrift, unsure of her feelings for the handsome lawyer who said he loved her, Nan fled to the estate of her beautiful distant Cousin Elizabeth in Hawaii.

Little did Nan suspect that the warm embrace of welcome would turn into a tightening ring of terror . . . and that in this sunlit paradise her safety was as fragile as the mysterious fan that was her passport into danger -- and her one hope of escape . . . .

Little Missee

The novel begins with the last exchange between Nan and her old amah (pages 3-5).

As I knelt beside an iron cot spread with a thin, worn quilt, I put my arms around a pitifully shrunken body, and tried to make my presence known. "It's Nan," I repeated again and again. "It's Nan. Your Nan, darling Ah Sam."

I thought I was too late, but after a moment or two a skeletal hand reached out for mine and pressed it feebly. For a brief instant vaguely staring, sick black eyes met mine and were cognizant.

Gung Hay Fat Choy, Little Missee . . ."

"Happy New Year to you, too, darling." My voice was unsteady.

After that she lay quietly in my arms for a few moments, her difficult breath a rasp, and then she started up abruptly against her pillow. Wildly, desperately, she tried to tell me something, but this time she was speaking Chinese and her words were meaningless to me. With an indescribable anguish I had to watch her eyes pleading with me to understand as they filled with a terrible longing to communicate, a terrible frustration.

"Dearest Ah Sam, it doesn't matter. Nothing matters. I'm here, I'm right here. . . ."

I turned to the brisk young Chinese doctor who stood at the foot of the bed replacing a thermometer and a stethoscope in his case, and of whom I had hardly been aware before. "What is she trying to tell me? Can you understand?"

The doctor snapped his case shut. "It is a garble of Hunan dialect, and I'm Cantonese -- sorry. But it's too late for her to make much sense now, anyway. She is gong fast." He glanced at the candles on the washstand and at a little teak table that was set out with a New Year's feast to propitiate the household gods, rice cakes and melon seeds and wine. "She hadn't expected the end so soon, I take it?"

"She wouldn't give in. She wouldn't admit it was anything serious, though she has been terribly ill all week." My arms tightened around Ah Sam. "You see . . . you see, she didn't want to face up to leaving me. She's been with me ever since I was born. She's never been able to realize I'm not a child anymore, or that I could manage without her."

Ah Sam's race

Ah Sam dies in the next paragraph. Nan thanks Doctor Yee for calling her. She tells him that she had wanted to put Ah Sam in a hospital but she insisted on staying in her own room, at the top some rickety stairs in a tenement building in Chinatown. Doctor Yee explains why (page 7).

"All the old people of my race want to die down here, in their own part of town, Miss Allen. To them, it is the next best thing to dying in China, and being buried with their ancestors."

Doctor tells Nan he will make the necessary reports but wonders about the funeral arrangements. Could he be of any help? Nan asks if he would be kind enough to call her attorneys, for they know Ah Sam, and they'll handle it for her. She hesitated before suggesting that he might ask for a certain attorney in the Trust Department, and then wondered to herself if he had noticed the hesitation.

She turns to leave, then looks toward the bed, and wonders allowed what it was Ah Sam had wanted to say. Doctor Yee says he wouldn't worry about it. All he could make out was something about a fan.

Reflections of character

Dr. Yee is a walk-on. He does not appear again. Why should Nan worry about whether he has noticed her hesitation? And why does she treat him like a servant?

Did Eyre intend for any of this to reflect Yee's character? Or was she only interested in reflecting Nan's?

Did she mean for readers to wonder what went through Doctor Yee's mind as he listened to Nan ask him to call the firm of Marshall, Martin and Hitchcock and ask for Mr. James Bradford in the Trust Department?

Or did Eyre herself think that it would have been unbecoming of a woman of Nan's wealth, if not race, for her to call her own attorneys to make arrangements for her own "darling" amah's funeral?

|