Earnest Hoberecht

The journalist who wanted to fly

By William Wetherall

First posted 15 August 2006

Last updated 10 November 2020

Earnest Hoberecht

1946 Japan as seen by American correspondents

•

1946 Tōkyō romansu

•

1947 Tokyo Romance

•

1947 Shears of Destiny

•

1947 Famous Americans

•

1948 Ladies and gentlemen

•

1961 Asia is my beat

As a novelist

Perfect love story for Occupied Japan

•

Ōkubo Yasuo: Hoberecht's "plagiarist"

•

Foujita's illustrations

•

Spanish editions

As a celebrity

American media

1946 "atom-bomb kiss"

•

1946 Time review

•

1947 Colliers $80,000 kiss

•

1947 Life Interracial romance

•

1957 Newsday Michener story

Japanese media

Fūfu seikatsu

•

Fujin gahō

•

Bungei shunjū

•

Chūō kōron

Afterlives

1999 The New York Times obituary

•

2015 Number 1 Shimbun tribute (FCCJ)

•

2021 Asia Ernie (Killen)

Families

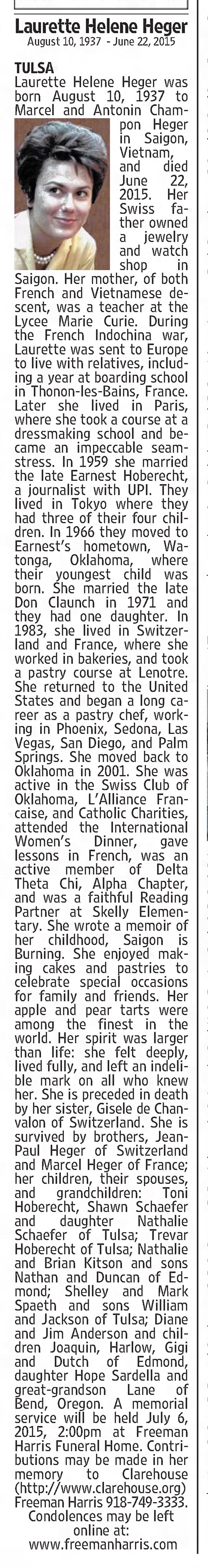

Laurette Helene Heger (Hoberecht, Clounch)

•

Mary Ann Shaklee (Karns, Hoberecht) Thurston

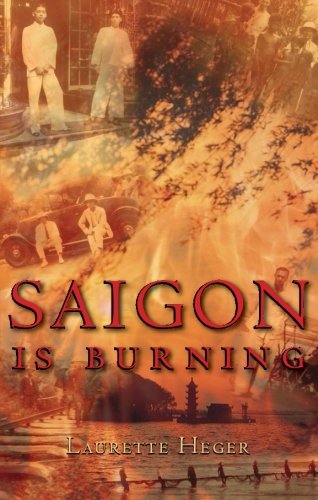

Saigon Is Burning

Laurette Heger's personal account of French Indochina and Vietnam

Earnest Hoberecht (1918-1999)Earnest Trevar Hoberecht, Jr. (1918-1999) was born in Watonga, in Blaine County, Oklahoma, on 1 January 1918, the son of Grace B. Hoberecht (1891-1956) and Earnest T. Hoberecht, Sr. (1889-1968). He passed away on 22 September 1999 and is buried, as are his parents, in the Hoberecht plot in Watonga IOOF Cemetery. Hoberecht married Laurette Helene Heger (1937-2015), a French national born in Saigon, in New Delhi, India, on 6 May 1959. See Laurette Helen Heger at the end of this article for a look at her life and a review of her 2006 book, Saigon Is Burning, an account of Southeast Asia during the Pacific War. 1946-03 Japan as seen by American correspondentsEarnest Hoberecht, well known among contemporary journalists in Asia as the United Press International (UPI) man in the region during and after the Pacific War, is best remembered today for the way he helped indoctrinate postwar Japanese society with (presumably) American attitudes toward marriage and sex. Before he took it upon himself to play this role, however, he contributed to a bilingual booklet published in March 1946, barely half a year after Japan's surrender and the start of the Allied Occuption in September 1945. Hoberecht was the lead-off writer among six American journalists who were asked by Mainichi Shimbun (�����V��), one of Japan's major national daily newspapers, to write a short impression of Japan, Japanese colophon�����V���� (�Ҏ�) The Japanese title reads "Amerika tokuha-in no mita Nihon inshōki" or "A chronicle of impressions of Japan as seen by American (special, foreign) corrspondents". The booklet was printed on 15 March and published on 20 March 1946. The stated price was 1 yen 50 sen. English particularsThe Mainichi Publishing Company (editor) The booklet is printed on pulp paper and bound in B6 size with a single staple in the middle of the spine. Hoberecht's contribution -- "Upon arriving in Japan by air" in English and "Sora kara no dai-ippo" (��̑���) or "First step from the sky" in Japanese -- consumed 6 pages in English and 4 in Japanese (see images to the right). The publication, bilingual from cover to cover, is at once a showcase of information disseminated in both English and Japanese, and an gesture to the hopes that Americans and Japanese will somehow get along -- as the journalists come across as a bunch of opinionated but open-minded and good-hearted good guys -- and even a girl, not to forget women. The publisher and distributor, Mainichi Shinbunsha, published Mainichi shinbun (�����V��) [Mainichi news / Daily news], one of Japan's big three national papers. Japanese edition1946-10 Tōkyō romansuHoberecht's first book in Japanese was the novel Tokyo Romance, which came out in Japanese in 1946 before it was published in English in 1947. �A�[�l�X�g�E�z�[�u���C�g �� Earnest Hoberecht (author) Papercover with jacket. The jacket shows a color drawing by Foujita Tsuguhau. The back of the jacket of the Yosha Bunko copy bears the brushed date of purchase, November 1946, and the name of the purchaser. The cover price is 18 yen. This edition includes 10 full-page line drawings by Foujita Tsuguharu (see below). 1947 Tokyo Romance (English edition)Earnest Hoberecht See Perfect love story for Occupied Japan (below) for an overview of the story of Tokyo Romance. The popularity of the Japanese edition of Tokyo Romance made Hoberecht a celebrity in Japan. See Earnest Hoberecht, novelist (below) for a look at some of the attention his celebrity status in Japan got in the U.S. press. See ōkubo Yasuo (below) for a look at the translator behind Hoberecht's popularity. Hoberecht followed Tokyo Romance with a novel about Oklahoma (see below) and a non-fiction book on famous Americans (next). Both of these works were published only in Japanese. He also wrote a few articles for general magazines, and numerous articles for men's and women's magazines which asked him to contribute his views on Japanese and American love and marriage (see below). 1947-04 Shears of Destiny�A�[�l�X�g�E�z�[�u���C�g �� Earnest Hoberecht (author) The translator's afterword is dated February 1947 (pages 285-286). Hoberecht claims he was motivated to write Shears of Destiny as a refutation of the images John Steinbeck created of the "Okies" who leave Oklahoma for California during the dust-bowl years of the Great Depression, in his novel The Grapes of Wrath (1939), which won Steinbeck a Pulitzer Prize in 1940 and the Nobel Prize in 1962. James Michener reports Hoberecht's account of how this novel came to be written in the 1957 Newsday interview he published after meeting Hoberecht in Japan (highlighting and [bracketed] remarks mine). My next novel [published in Japanese after Tokyo Romance] is probably the finest thing I ever did and I'm deeply sorry it had to be published in Japanese because it's a book Americans ought to read. It clears up some very misleading matters. It's called Shears of Destiny. I wrote it long before the war and couldn't find an American publisher, being then just an unknown, and it turned up in the box of old papers my father shipped me. I had it translated by the plagiarizer [Ōkubo Yasuo] right into Japanese without additional editing because it was a well constructed story just as I told it and I had already gone over it once when I sent it to the American publishers. The Japanese loved it and it made a lot of money. I think Americans would go for it, too, but now it's enshrined as a part of Japanese literature. In it I prove that the Okies written about by John Steinbeck didn't come from Oklahoma at all. They were mostly from Georgia, a very poor sort of people, with some useless Texa[n]s and some no-goods from Mississippi thrown in. They just happened to be passing through Oklahoma and if Steinbeck had taken the trouble to study the facts a little deeper he'd have realized that he wasn't writing about Okies at all but about these no-goods from other states. I'm not criticizing Steinbeck, you understand. Does no good for one literary man to knife another, but I did have to write this book to clear Oklahoma of the unfair stigma Steinbeck's book had cast upon my state. The harm done by one book like Steinbeck's outweighs all the good of a musical like Oklahoma. Divine retributionSome communities in the United States have at times banned Grapes of Wrath from libraries and schools and even made possession of the novel a crime. As soon as it was published, it was banned in Kern County, California, where much of the story is set. By the time Hoberecht died in 1999, some scholars had begun to undermine the credibility of Grapes of Wrath as a work of social history, which is how it has usually been read in schools -- though for reasons unlike those Hoberecht gave Michener. Steinbeck was not, however, the only one to embrace the images of Oklahoma and Okies he disseminated in his novel. A number of contemporary works, like An American Exodus: A Record of Human Erosion (New York: Reynal & Hitchcock, 1939), a photographic essay by Dorothea Lange and Paul S. Taylor, cultivated the soil in which it was possible for Americans to read Grapes of Wrath as an accurate portrait of the times. Earnest Hoberecht, as proud an Oklahoman as was ever born, read it very differently. 1947-09 Fifty Famous AmericansHoberecht wrote other novels (see below) and numerous magazine article (see below). Non-fiction books that came out during his stays in Japan include Fifty Famous Americans (1947) and Asia is my beat (1961). �A�[�l�X�g�E�z�[�u���C�g �� Earnest Hoberecht (author) Softcover. Includes 6 pages of black-and-white photographs of faces of 36 civilians and 17 military and civilian occupation personnel. 1948-07 Ladies and gentlemen: Democratic Etiquette�A�[�l�X�g�E�z�[�u���C�g �� Earnest Hoberecht (author) This book has the smell of a company-initiated project to capitalize Earnest Hoberecht's fame in Japan at the time it was published. The name of the translator appears to be a pseudonym, possibly of a team of translators and writers hired by the publisher -- Radio News -- to translate and/or adapt Hoberecht's views of American-style "democratic etiquette" between "ladies" and "gentlemen". The table of contents is preceded by a 2-page preface attributed to Col. Lawrence Elliot Bunker as Adjutant to Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers General Douglas MacArthur. Bunker served as MacArthur's chief aide from April 1946 to November 1952. He served MacArthur both in Japan from 6 months after MacArthur established his headquarters in Tokyo during the Occupation of Japan, and in New York for 18 months after Truman recalled MacArthur in April 1951. Bunker later became the first vice-president of the MacArthur Memorial Foundation in Norfolk. The back of the obi cites Bunker's preface after conspicuously declaring "Gen. Mac's aide Col. Bunker says:" in typical "Confucius says:" style. For a fascinating interview with Bunker about MacArthur, see Oral History Interview with Col. Laurence E. Bunker, Chief aide to General Douglas MacArthur, April 1946 to November 1952, conducted for the Harry S. Truman Library by Benedict K. Zobrist, at Independence, Missouri, 14 December 1976. The table of contents is followed by the translator's undated 3-page introduction to the book and its author, Knowledge of etiquette in America is billed as something that would be useful to "present-day Japanese who are becoming international" (kokusai-teki ni naritsutsu aru genzai no Nihonjin ���ۓI�ɂȂ�T���錻�݂̓��{�l) (page 7). Next comes Hoberecht's 5-page introduction -- dated 1948, Tokyo -- leading off with the observation -- "There is nothing as cheap, and moreover of such high value, as good manners" (Yoi gyōgi sahō hodo, anchi de, shikamo kachi no takai mono wa hoka ni nai de arou �ǂ��s���@�قǁA���u�ŁA���������l�̍������̂͂ق��ɂȂ��ł��낤) (page 9) -- one of numerous variations of "good manners cost nothing but are priceless" cliche. The book is for everyone who wants to know everything about basic etiquette (reigi sahō ��V��@) in America. The main text opens with a look at "shukujo" (�i��) as opposed to "shinshi" (�a�m). The later is "jentoruman" (�W�F���g���}��), which needs no introduction. "Shukujo" is said to mean "gentle-woman" (jentoru uuman �W�F���g���E�E�[�}��), but in English is called "lady" -- meaning a "[married] woman" (fujin �w�l) of good birth and good upbringing (page 1). The book covers all manner of social situations, and includes a section on how to address American Army and Navy officers and officials (pages 205-207). The Japanese text is sprinkled with English expressions, and there are examples of how to word requests for hotel reservations and invitation cards, and how to sign names. The book covers table manners, and there is no shortage of advice regarding the importance of "ladies first". 1961 Asia is my beatEarnest Hoberecht -- at the peak of his career, a veteran foreign correspondent in Japan, one of several who had honed their reporting skills during the Pacific War and its aftermath and qualified as "Old Asia Hands" among their younger peers -- had been married a year, had become a father, and was probably a bit bored with his job as head of United Press International's Asia Division, when he decided to write a book about his nearly 20-years of life journalist. Earnest Hoberecht Hoberecht kicks of his story like this (page 9). THE NEWS BUSINESS is the greatest business in the world. The best job in the news business is to be a foreign correspondent. The best place to be a foreign correspondent is in Asia. Hoberecht had been "roaming around the Pacific and Asia" since 1942. Asia is my beat is an ear-to-the-ground personal account of the Pacific-and-Asia he witnessed, survived in, and imagined as a journalist during and after World War II -- including stints as a war correspondent during the Pacific War (1941-1945) -- the civil wars in China culminating in the founding of the People's Republic of China (PRC) in 1949 and the retreat of the government of the Republic of China (ROC) to Taiwan province -- the Korean War (1950-1953) -- the French Indochina war in Vietnam (1946-1954) -- and the fighting between ROC and PRC during the Taiwan Straits crisis of 1955, over the Tachens (Dachen islands), then the home of the temporary government of Chekiang province, which ROC was militarily and diplomatically forced to evacuate and allow to fall to PRC forces. The book also covers the Allied Occupation of Japan, General MacArthur, General Tojo and the war crimes trials in Tokyo, Hoberecht's interview with the emperor of Japan in a Tokyo department store, his interview with Henry Pu-yi, the last emperor of China, the Dalai Lama, even India, Pakistan and Afghanistan, which were also parts of his turf at the height of his career. China and Taiwan (Formosa)Chapter 6 (pages 69-77) is one of those incredibly interesting "fly on the wall" accounts of what was going on -- and not going on -- at the time the United States was dealing with the question of whether to "Save Formosa" -- the Republic of China -- from the People's Republic of China. PRC, founded in 1949 following a revolutionary war against ROC, was bent on completing the revolution by militarily invading and capturing Taiwan, which had become the redoubt of the ROC government when retreating to the island in exile. As I write this in 2020, 75 years after the end of the Pacific War, the world continues to witness the geopolitical aftereffects of the breakup of the Empire of Japan by the Allied Powers. Of crucial importance today is the fact that, unlike most postwar settlements in recent centuries, territories were separated from the Empire of Japan without designating successor states in peace or other treaties. There was only "one China" in 1945 when ROC accepted Japan's surrender of Taiwan. ROC, then the sole candidate for successorship, immediately incorporated Taiwan into its territory as a province. But "two Chinas" existed by the time the San Francisco Peace Treaty was drafted and signed in 1951 -- without the participation of either China. The treaty confirmed that Japan had relinquished Taiwan, but there were no provisions for successorship. Chōsen faced a somewhat different disposition because there was no Korean state at the time Japan surrendered. A successor state had to be created. And by the time the peace treaty was made, there were "two Koreas" -- neither had been at war with Japan or otherwise qualified as parties to the treaty -- and both of which claimed sovereignty over Chōsen. As with Taiwan, the peace treaty confirmed only that Japan had relinquished its claims to Chōsen, without specifying the successor state or states. Chapter 7 (pages 78-83), on the heels of the "Save Formosa" question, is dedicated to the world's oldest profession -- which in Japan, Hoberecht says, "had been developed to a fine art". Oriental womenThe better part of Chapter 18 (pages 165-178) is devoted to a comparison of a dozen nationalities of "Oriental women" -- by way of addressing the pressing issue of whether there is anything to the rumors they make good wives. Hoberecht finds "strong evidence" to support that they do (pages 167-198). In Japan, for example, between September, 1945 and July, 1956, there were 26,101 Americans who married Japanese girls. Hoberecht then cautions that other rumors -- such as "Oriental women are treated as mere possessions and have no rights" -- are misconceptions, and says -- "Ask the man who thinks he owns one." "to retard the development of family life"In Chapter 1, which describes what he dubs the world's greatest profession, Hoberecht wonders if foreign correspondents are a "peculiar breed", and he cites statistics from a survey of full-time correspondents employed by American commercial organizations. Contrary to popular belief, he says, correspondents [practically all of whom were then men] don't drink more than American males generally. "Probably no more than three or four percent of the correspondents are intemperate drinkers. However, the vocation affects the prospects of family life (pages 10-11). -- Foreign correspondence as a way of earning a living seems to retard the development of family life among its practitioners. Nearly one-fifth of the [209] correspondents replying to survey questions [among the 450 polled] were not married; one-fourth had no children. Three-fifths of the married correspondents did not have their first child until they were 31 or older. Hoberecht was 31 when he, an American, married a French woman of French, Vietnamese, and Swiss ancestry in 1959. And he was 32 when his first child was born, the year before the publication of Asia is my beat -- which reads like a good conversation that jumps from one subject to another without warning, and without failing to interest and delight. Asia is my beat dust jacket photoThe photo on the dust jacket of Asia is my beat appears to show Ernie Hoberecht alone with General Douglas MacArthur. The original, however, shows two other men beside Hoberecht and MacArthur. Whether the doctoring was Hoberecht's idea, or that of the book's publisher, Charles E. Tuttle, is not reported. For the full story, see Chapter 21 of Patrick J. Killen's 2021 biography Asia Ernie (below). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Earnest Hoberecht as a novelist |

|

By all accounts, Earnest Hoberecht (1918-1987) was a character. He graduated from the University of Oklahoma in 1941 with a degree in journalism. By the next year, after a few months reporting for local papers, he was chasing the Pacific War, during which he would make his mark among the now practically exctint species of foreign correspondents for whom getting to the bottom of a story was calling rather than a job. Hoberecht was also a proud Oklahoman and romantic who wanted very much to be a novelist. For a few years in Japan right after the Pacific War -- until James Michener visited the country in the early 1950s and set the record straight -- many Japanese were under the impression that Hoberecht was another Hemingway, Faulkner, Lewis, Fitzgerald, or Buck. Asked what he thought of Hoberecht, Michener told a gathering of college students that he had not been able to "keep up with the younger German writers" (Newsday, 1957). The audience laughed, and afterward a graduate student, who was writing a thesis to prove that Hoberecht was America's greatest novelist, told Michener he was surprised he didn't know that Hoberecht was an American. Had Hoberecht (pronounced "hobright") not followed MacArthur to Japan at the end of the Pacific War as a United Press correspondent, the world would probably never have known about his aspirations to write fiction. As it is, the world today -- its memory mercilessly (or mercifully) short and selective -- can barely recall Hoberecht's name, much less the titles of the two novels he published in Japanese -- the first of which outsold by a factor of ten its later English edition. The second -- which Hoberecht had written much earlier and seems to have taken more pride in -- has never seen the light of day in English. |

Perfect love story for Occupied Japan"a problem we shall all hear more about in this post-war world"Tokyo Romance reads more like a plea for ending taboos about mixed marriage than as a novel. It is so boring that one can't put it down -- simply out of curiosity about how an obviously competent writer of reportage handles plot and character. The ultra simplicity of the story -- of true love between an American journalist with a jeep and Japan's most popular movie star -- makes it ideally suited as a guidebook for Japanese female readers who want a vicarious experience of what it might feel like to be seduced by, and to counter seduce, an American in Occupied Japan who spots in "flesh and blood" -- the woman whose photograph he'd so often seen in the debris of battlefields -- standing before him "like the fulfillment of a dream" (page 32). The front flap of the dust jacket of the English edition describes the story as shown in the box to the right. Romantic thriller as autobiographic fantasyThe 28 October 1946 Time_magazine review (above) notes that Kent Wood had found in Japanese strongholds in the Pacific "faded pin-up pictures of an almond-eyed cinema star (who looked a lot like Movie Actress Yukiko Todoroki, a good friend of the author." The November 1946 issue of Sooner Magazine, published by the University of Oklahoma Association, made this statement in its alumni-makes-good report (Vol. XIX, No. 3, page 2). One of the most widely publicized [of Hoberecht's] stories was his account of kissing Japan's first lady of the screen, Miss Todoroki, such osculation apparently being newsworthy because of its rarity in the land of the cherry blossom. The 7 April 1947 issue of Life magazine (above) ends the introduction to its photoplay of Tokyo Romance like this (page 107). Author Hoberecht is a genial 29-year-old Oklahoman who had a real-life "Tokyo romance" with a Japanese actress. Although it did not end happily, his literary efforts have earned him nearly $100,000. He has found, however, that occupation laws forbid his taking the profits home. Rumors are that Hoberecht met the actress Todoroki Yukiko (���[�N�q 1917-1967), who at the time was married to the film director Makino Masahiro (�}�L�m���� 1908-1993). Todoroki had migrated to the silver screen in 1937 after a 5-year stint as a Takarazuka Revue star. She became popular among movie fans for her role as Sayo in Kurosawa Akira's Sugata Sanshirō (1943) and Zoku Sugata Sanshirō (1945). She is also remembered for her appearances in Mizoguchi Kenji's Musashino Fujin (1951) and Ichikawa Kon's Seishin kaidan (1955), among a number of other films she made before her early death from hepatitis at age 49. |

Ōkubo YasuoHoberecht's "plagiarist"Hoberecht's partner in literary crime was Ōkubo Yasuo (1905-1987), a student of English literature and a translator, and one of Japan's most popular translators at the time. Ōkubo is most famous for for his translation of Margaret Mitchell's Gone With the Wind (1936) as Kaze to tomo ni saranu in 1938 the year before the release of the movie. James Michener, in a 1957 Newsday story about Hoberecht (see below), quoted Hoberecht as describing Ōkubo as "the young man in Tokyo who plagiarized Gone with the Wind. Very gifted boy. I employed him to work on my books, and all the skill he had applied to his plagiarism he applied to my work." Edward Seidensticker has characterized translators as "counterfeiters" but "plagiarists" may be the more fitting metaphor. Gone With the WindGone With the Wind has been a screen, stage, and manga favorite in Japan since the end of the Pacific War. Ōkubo translated Margaret Mitchell's 1936 novel as Kaze to tomo ni sarunu. This translation was published in three volumes by Mikasa Shobo in 1938, the year before the movie came out in the United States. Kaze to tomo ni sarunu has been a staple in the repertoire of the all-female Takarazuka Revue since the company produced its first musical adatation of the story in 1977. Every production has been cast and arranged differently. In the first Takarazuka production, the main character was Rhett Butler, appropriately played by Haruna Yuri, the most popular star at the time, known for her strong male performances, and made up to look very much like Clark Gable, who got top billing in the film. But many later productions have cast the top star as Scarlett O'Hara, who is the main protagonist in the the novel. Ōkubo's translation is still in print. It's publishing history is somewhat interesting. In 1949 Mikasa reissued the translation in five volumes as the first work in the "Eibeihen" group of its "Gendai sekai bungaku" series. Only Ōkubo's names as given as translator. In 1952 Mikasa put out a scenario of the movie with 16 pages of stills, showing Ōkubo Yasuso as the "supervising editor" (kanshu). In 1953 Mikasa published Ōkubo's translation as a boxed two-volume "bekkan" (supplement) of its Gendai sekai bungaku zenshu. In 1955 Mikasa published a boxed six-volume edition in "shinsho" (taller pocketbook) size, showing for the first time Takeuchi Michinosuke's name alongside Ōkubo's as translator. In 1977 Mikasa released a three-volume version showing both Ōkubo Yasuo and Takeuchi Michinosuke as translators. Grapes of WrathŌkubo translated some of the most popular works of the most popular writers, including O'Henry, Ellery Queen, Agatha Christie, John Steinbeck (Grapes of Wrath), Daphne du Maurier (Rebecca), Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Mark Twain (Tom Sawyer), Vladimir Nabokov (Lolita), William Faulkner (The Wild Palms), Charlotte Bronte (Jane Eyre), Ernest Hemingway (The Sun Also Rise, Farewell to Arms, For Whom the Bell Tolls), Margaret Mitchell (Gone Withthe Wind), and Henry Miller (Tropic of Cancer, Tropic of Capricorn), among others. Ōkubo translated Grapes of Wrath (1939) as Ikari no budo [Graphs of wrath] (Hayakawa Shobo, 1967) -- fifteen years after he translated Shears of Destiny, Hoberecht's fictional effort to correct Steinbeck's images of Oklahoma (see below). Day of InfamyŌkubo also translated a few non-fiction works, including Walter Lord's Day of Infamy (1957). Hametsu no hi: Junigatsu yoka no Shinjuwan [Day of destruction: Pearl Harbor on December 8] (Hayakawa Shobo, 1957) came out in Japan the same year it became a bestseller in the United States. |

Foujita's illustrationsThe Japanese edition of Tokyo Romance includes ten full-page illustrations drawn by Foujita Tsuguharu (1886-1968). They are dispersed throughout the story but more frequently toward the beginning and most frequently toward the end. The illustrations are encountered in the book while reading right to left, but here they are shown left to right. Though printed on yellowing pulp paper, the drawings are much sharper than they appear in these scans. |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Spanish editionsThe 1947 English edition of Tokyo Romance was translated into Spanish, and at least three differently designed editions were published as Romance en Tokio between 1950 and 1958. 1950 Novelas y Cuentos editionThe first edition was published in the Sunday, 27 August 1950 issue of Novelas y Cuentos [Novels and tales], a literary magazine (Revista Literaria) published in Madrid. Earnest Hoberecht The translator's name is not given. The text, however, is identical to that of the 1958 Libros Plaza (Barcelona) edition, which is attributed to Teresa Oyarzun. The graphics of this 1950 magazine edition appear to be attributed to DIANA, Artes Gráficas. The 2nd paragraph of the biographical sketch of Earnest Hoberecht above the "Preliminary Chapter" translates as follows. The large publishing houses and radio stations today besiege Hoberecht asking him for articles, [short] stories, novels, and radiophonic "serials". The Hoberecht Club has sprung up with thousands of admirers, and a musical "interpretation" of "ROMANCE IN TOKYO" has even been released. For the most part, this and other publicity was adapted directly from the back cover blurbs of the English edition, which include these lines. Publishers are swamping him with requests to do magazine articles, newspaper serials, short stories and a dozen more books. Hoberecht Fan Clubs have sprung up all over Japan with a membership in the thousands. And already a musical version of TOKYO ROMANCE is being shown on the Tokyo stage. Note that "emisoras de radio" has been added to the Spanish version, which transforms "newspaper serials" in the English version to "'seriales' radiofonicoes" in the Spanish version. At the present time (2020), I am unable to determine the foundation for these changes. 1958 Novelas y Cuentos editionA tall paperback edition was put out in 1958 by Earnest Hoberecht The back cover portrait is from the back flap of the English editon. The biographical details are also culled from the English editon. The Spanish blurb makes no mention of newspaper (or radio) serials, but does remark "Incluso s ha estrenado una versión musical de ROMANCE EN TOKIO" [Even a musical version of ROMANCE IN TOKYO has even been released]. |

||||||||

|

Earnest Hoberecht as a celebrity |

|

Publishing in Japan was increasing suppressed for political reasons during the years leading up to the Pacific War. Printed matter was more heavily censored during the war, and further constrained by paper shortages that briefly continued after the war. Liberated from such limitations, newspaper, magazine, and book publishers scrambled for paper, ink, and presses to meet the demand for information and entertainment, subject only to the more permissive content rules set down by the Occupation government. Japan's publishing industry, one of the healthiest in the world before World War II, quickly recovered, and it went on to be what -- but the end of the 20th century -- could probably boast as having the highest per-capita rate of print media consumption in the world. As of this writing, nearly two decades into the 21st century, Japan's print media is rapidly giving way to the inroads made by Internet media. Television did not begin to spread until the mid 1950s, and so popular magazines, novels, and movies were the main sources of entertainment during the late 1940s and into the 1960s, when Earnest Hoberecht became a celebrity writer in Jaan. |

|

American media |

28 October 1946 Time reviewTime Magazine reviewed Tokyo Romance in its 28 October 1946 issue. The review can be retrieved from TIME Archive on Time's website. I have also reproduced it here.

|

1947-03-08 Colliers"The $80,000 Kiss"Weldon James The deck of the article reads as follows. How Earnest Hoberecht from Oklahoma became a Tokyo millionaire and the most famous writer in Japan simply by embracing a Japanese movie queen Actress Hideko Mimura was fairly popular but was not exactly in the "movie queen" class. And if Earnest Hoberecht became a millionaire, it was in Japanese yen, not U.S. dollars. But the hype made it a good story -- Hoberecht's stock in trade, and that of his journalist buddies. And Weldon James had as much fun writing this piece and Collier's subscribers undoubtedly had reading it -- even if they knew nothing about Japan or even Hoberecht for that matter -- and most most likely didn't. The photographer, Horace Bristol (1908-1997), who was also a journalist, later married Yamashita Masako (1928-2005) some 10 years later and became an architect ("Konketsuji" website). See GI Bebii: Beihei to Nihon musume no konketsuji on the "Graphic arts" page in the "Culture" section of this website for scans of and commentary on Bristol's 1950 photogravure study of mixed-blood children in Occupied Japan ("Konketsuji" website). |

1947-04-07 Life"Interracial Romance"Collier's, a thinner rag more in the class of Saturday Evening Post, beat Life to the punch with its $80,000 kiss story. But Life topped it with an exclusive look at Hoberecht and his friends hamming it up on a Daiei Films studio set. John Florea (photographer) Images to right The article opens as follows. An unfortunate specimen of U.S. culture is being studied avidly throughout Japan. Although Tokyo Romance by Earnest Hoberecht is possibly the worst novel of modern times, a Japanese translation is selling like rice cakes. Sales have reached 213,000 copies and, if enough paper becomes available, they may hit half a million. Life photographer John Florea apparently came up with the idea of getting some of Hoberecht's journalist friends and other amateurs -- including Hoberecht in a brief cameo role as himself -- acting out the novel in several staged scenes, apparently at a Daei studio. CastThe cast, according to the article, was as follows.

Just a bunch of (mostly) boys having serious fun. Rumors of stage and film versionsBlurbs on the English edition of Tokyo Romance, and comments attributed to Hoberecht in newspaper and magazine articles, and other reports, allude to a musical production and bidding for film rights. Given the popularity of the Japanese edition of the novel, stage and movie versions would not be surprising. As of this writing (2020), however, I haven't seen any sign of such productions in Japanese media. And judging from what I have seen in English media, the closest Hoberecht came to seeing a dramatization of his story was on the Daiei set as shot by John Florea in this Collier's piece. |

1946 Atom-bomb kiss saves democracyJames Michener's 1947 Newsday report on EarnestThe University of Oklahoma Association, quick on the draw, immediately published a slightly abridged version of a long feature by James A. Mitchener wrote for a magazine distributed with the Newsday, in the February 1957 edition of Sooner Magazine (Vol. XXIX, No. 6, pages 14-15, 29-32), including photographs of Hoberecht with ROK's Syngman Rhee, ROC's Chiang Kai-shek, and America's John Foster Dulles. The following excerpt is based on a digital copy posted on The Downholders (www.downhold.org), "a free site intended to preserve the history and lore of United Press International and its predecessor agencies, United Press and International News Service, their alumni (the Downholders), and the people who still work there." |

||

"America's Greatest Writer"By James A. MitchenerEvery word of this story is literally true, [ Omitted ] "My first book was "Tokyo Diary." Somewhere I had heard a title like that and it sounded good. I explained to the Japanese how an American correspondent landed in Japan, what he thought, what he saw, how he liked the Japanese people. The book sold like mad and we made a pile of money. There's a lot of misinformation about how much money I made. Some A.P. men claim I made more than two million dollars. It wasn't that much, I can assure you. But to me, even more important than the money is the fact that all Japan has recognized me as a friend. I can go anywhere in Japan and people speak of me as Hoberecht, the sincere friend of Japan. I think my atom-bomb kiss had something to do with that. MacArthur announced that he wanted the Japanese to stop making blood-and-thunder samurai movies of revenge and get more in the American tradition. But how can you have an American movie if the hero doesn't kiss the heroine? I happened to visit a Japanese movie company that was trying its best to make an American-style love story, but the heroine, acted by a sweet little girl, had never been kissed. In fact, she had never seen a kiss. There was no word in the language for it. You might say that right then and there I seen my duty and I done it. I stepped forward, bowed and gave the movie star a big kiss. She fainted. Yep, she fainted dead away and there was a photographer there and the pictures were shown all around the world. People in Japan went crazy to hear more about this kissing racket. They demanded to see this correspondent who was so good at kissing that girls fainted. A.P. men have started the rumor that I actually set up kissing schools where I collected fees. That's a lie, an outright lie. I did permit a couple of other movie stars to take lessons, but none of them fainted and gradually the craze died out. You can say, however, that Japan's first democratic movie would never have been made without my assistance. "Looking back on that atom-bomb kiss, I'd say it hurt me more than helped, because when my greatest novel was published everyone was certain that I was the hero and the movie star was the heroine. That isn't true. This second book was the result of much more careful planning than that. When Zenkichi Masunaga saw that he was cleaning up on "Tokyo Diary" he came to me with a proposition that I should write a powerful romantic novel about modern Japan. I went right to work and in four days was a quarter of the way through it. I called it Love Me, Tomiko. And right there Masunaga showed his genius. He said he had a much bigger idea than a book with such a name. He introduced me to a brilliant young newspaperman, Masaru Fujimoto, Ambassador Grew's personal interpreter. You can read about him in Grew's book. Masunaga said that the three of us would constitute a brain trust. So we sat down and planned this great novel as coldly as you would plan building a skyscraper or laying a railroad through the mountains. "Masunaga said the title had to have the word Romance in it, so we started with that. Then Fujimoto said that Tokyo had always been the most romantic city in Japan and I cried, 'That's it. Because it ties in with my first book, Tokyo Diary.' I wanted the people of Japan to associate my name with a series of good books. So that was it. I wrote "Tokyo Romance" in 27 days, but I would like to give some of the credit to the brilliant young man who translated it. He's the one who did such a splendid job plagiarizing "Gone with the Wind" into a Japanese setting. He could handle love scenes with unusual delicacy and before my novel appeared his version of Gone with the Wind was the biggest seller Japan had ever had in the romantic field. Now, of course, "Tokyo Romance" holds the record. It's a little difficult for me to explain what happened next because I specifically didn't want to know, but SCAP (Supreme Command, Allied Powers) had a rigid rule that no book could have more paper than that needed for 2,500 copies, but as soon as the first readers started telling everyone how sensational my book was we knew that here was something bigger than petty regulations. I still don't know how Masunaga got the paper, but he published 300,000 copies in two months and kept right on going. I'm perfectly happy not to know how he got the paper, but some A.P. man started the rumor that Masunaga had printed over a million copies and had paid me for only 300,000, but that's a lie. I trusted Masunaga implicitly, but one of my men just happened to find the printing plant that printed the little numbered papers that appear in the back of each book. They're called chops. So my man sneaked into the chop plant each night to check off how many had been printed. Masunaga was completely honest. [ Omitted ] |

|

|

Japan's first "democratic kiss"Journalists have fun when they can. And Earnest Hoberecht had a reputation for having fun while pursuing the most serious current events of the day. His most famous fun piece was a report on how MacArthur and he himself saved democracy in Japan by tutoring a movie actress in the "art of osculation". The full, abridged, and rewritten wire report ran under numerous headlines written by local editors. Above Right News Writer Real Hero Of Jap Mug Show / Teaches Leading Lady Finer Points of Osculation All Mac's Idea First Jap Kiss Yank Reporter Coaches Jap Screen Star for First Kiss M'Arthur's Idea |

|

|

Shōchiku, 11 April 1946, 22 minutesO-warai shūkan: Hanamuko sōdō ki"The Bridegroom's Trouble Diary" refers to O-warai shūkan: Hanamuko sōdō ki (�����T�ԁ@�Ԗ������L) -- "Laughter week: Bridegroom commotion account" -- a romance comedy written and directed by Tanaka Tadao (�c�����v). The movie was shot at Shōchiku's Ōfuna studio and ran only 22 minutes. It was released on 11 April 1946 with two other similarly short "O-warai shūkan" comedies. Takaka had assisted with the direction of 4 previous Shūchiku films between 1934 and 1937. This film was his debut as a director and screenwriter but his filmography ends here. The cast were mostly Shōchiku casting central workhorses who appeared in one after another of the films the company, after the lean war years, began to crank out at the rate of 2 or 3 a week. The main cast was as follows. Sakamoto Takeshi (��{�� 1899-1974) as Genshichi (����), Mineko's father An synopsis in a movie database roughly translates like this. Inoue and Minako are in love, and Minako persuades the timid Inoue to ask her father for her hand. Inoue agrees and returns to his apartment. His friend Katō comes and says a tailor is coming to collect on a loan and asks Inoue to help him out. Minako tells her father Gen'ichi that Inoue will be coming the next day, and Gen'ichi goes to Inoue's apartment to appraise his daughter's lover. Inoue takes Gen'ichi for the money lender and chases him off, and Gen'ichi leaves in a huff of anger. The next day, when dressing to meet Minako's father, Inoue notices that his jacket had been torn in the scuffle with the debt collector, and so he wears the jacket the debt collector had left behind. Inoue, seeing Mineko's father, is suprised, and quickly takes off the jacket and runs off. The misunderstanding is eventually resolved and Inoue and Minako are united in marriage. Hoborecht's kissing article went out on the wire in late March, about the time the movie -- which was probably shot in only a day -- was being readied for release. The photograph credited to Acme Photo, published with The Honolulu Advertiser version of the U.P. story (above right), appears to be a still from the movie, probably from the last scene. |

||

|

Japanese media |

Hoberecht's afterlives

Obituaries and later tributes

Most people have a single afterlife created by the people they leave behind, who dispose of their biological remains and property. They rate a single obituary, if any, in a local paper. And within two or three generations, they are probably forgotten among the living.

Earnest Trevar Hoberecht II has had several afterlives in the form of memorial articles written about him by people who remember him years after he passed away -- and webpages like this, by people who didn't know him but have reason to investigate his life and attempt to illuminate some of his achievements.

As I write this, it occurs to me that -- by memorializing Hoberecht like this -- I am underwriting my own digital immortality. What, though, are the odds that a century or two from now, anyone will stumble across this article in an archive of old websites?

1999 The New York Times obituaryEarnest Hobertecht rated a 926-word obituary by Douglas Martin at the Metropolitan Desk in the Sunday, 26 September 1999 edition of The New York Times, as follows.

|

2015 Number 1 Shimbun tribute (FCCJ)The Foreign Correspondents Club of Japan (FCCJ) paid tribute to Earnest Hoberecht in the March 2015 issue of the monthly magazine Number 1 Shimbun, as copied and reformatted below. The "Shimbun Alley" was the name of the side street where FCCJ set up operation during the Allied Occupation of Japan. Practically all contemporary journalists who filed reports from its facilities are alive as I write this today in 2019. However, the legends are still being whispered among the few younger journalists who heard them directly from the few contemporaies who were still in town shortly after the turn of the 20th to 21st centuries.

|

Patrick J. Killen 2021Asia ErniePatrick J. Killen Patrick J. Killen (1929-2023), who was 92 when this book, was published, died in June 2023 at age 93, leaving his wife Midaeja (Miyako) Kim Killen (b1957) and daughter Kimberly (Kimbo) Killen. Both his wife and their daughter were born in Japan. He married Kim, then a nurse, in 1996. The family moved to Dallas, Texas, when he retired in 2004. "One of the beauties about working for UPI was that having absolutely no familiarity with the subject of a story was never a drawback." Killen's biography of Earnest Trevar Hoberecht, Jr. (1918-1999) is interlaced with glimpses of the lives of other journalists who crossed paths with Hoberecht, particularly other UPI correspondents, including Killen himself, who joined UPI in 1956. Killen's overview of Hoberecht's Asia is my beat is very revealing. Killen discloses that Hoberecht wanted UPI to buy 2,000 to 3,000 copies of his book for promotional use. His budget for the Asia Division, which he oversaw, included the purchase of 500 copies for Asian clients alone -- to "[show] how the UPI scoops the pants off the opposition in Asia" (page 124). Of course it was mostly about Hoberecht blowing his own horn, and making a little money on the side. In another anecdote, Killen writes that, when welcoming the journalist Richard "Dick" Stone (1941-2022) to UPI, Hoberecht asked Stone if he had a copy of Asia is my beat to sign. Stone said no and asked where he could get a copy. Hoberecht pulled one out of a box in the coat closet and inscribed it to Stone. Stone's first pay slip showed that "[Hoberecht] had deducted the price of the book -- at retail" (page 125). Judging books by their coverThe chapter on Asia is my beat, however, with the story behind the obviously doctored photo on its dust jacket. I say "obviously" because that was my impression when I first saw it. I have a couple of hundred wire-service press photos from morgues of newspapers that have put their older material on the market. Several of the photos have been marked up for editing to to suit the purposes of the newspaper. Most editing involved only cropping to select the most important part of the photograph. Some editing, though, involved deleting backgrounds that were too dark or too cluttered, or otherwise competed too much with the main subject of the photo. So I imagined that the unblemished gray background of the dust jacket photo was the result of brushing out a lot of clutter to highlight MacArthur and Hoberecht and also to brighten the cover. Seeing the original photo in Killen's book, however, reminded me that -- not only should one never judge a book by its cover, but one should never assume the authenticity of a photograph that has not been honestly declared unedited or unfiltered. "Photoshopped"Of interest here is that Killen, in the text, writes that the two other men in the photo were "airbrushed out" -- but in the caption, he says they were "Photoshopped out" -- of the picture (pages 122-123). Whether the background was literally "airbrushed out" is not clear -- there were other ways to cut out backgrounds. But for certain it was not "Photoshopped out" -- in 1961. Saigon RomanceA chapter in the back of the book tells the interesting story of the journalist Ray Herndon (1938-2015), who joined in UPI in 1962 and covered the wars in Southeast Asia in the 1960s and 1970s. Like Hoberecht, he married a Vietnamese woman of partly French descent -- in the summer of 1964, before the Tonkin Gulf incident that fall triggered the start of the American phase of the Vietnam War that fall. In Herndon's words, as Killen cites them (page 205, see image to right): "In the summer of 1964, we [Annie Elise Porcher and I] got married three times -- first by the Vietnamese civil authorities, then by the French Consul, and finally in Saigon's Hoa Binh Cathedral by Father Patrick O'Conner, the Irish priest who was the correspondent of the National Catholic News Service." The tidbit is important as evidence that a marriage in the Republic of Vietnam between a national of ROV (Annie Porcher) and an alien (Ray Herndon), was legally confirmed in exactly the same manner as a marriage in Japan between a national of Japan and an alien. The couple first marries before a civil authority of the country in which the marriage takes place, and then marries before a consular authority of the country of the alien spouse. This "double marriage" routine is generally all that is required to insure that the marriage is legal under the laws of both countries. The 3rd marriage, in the form of a religious or other ceremony, is private -- and, depending on the ceremony, may take place before or after the completion of of the two legal procedures. In other words, the religious or other private ceremony -- while socially significant for the concerned parties, families, and friends -- generally have no legal effects in the eyes of the concerned governments. Not a few mixed-nationality couples, unaware of the need to complete civil and consular procedures, have discovered after a private ceremony that they are not legally married. |

||||||

Hoberecht's families

Earnest Trevar Hoberecht II (1918-1999) appears to have married twice -- first to Laurette Heger (1937-2015) in 1959 when he was 41 -- then to Mary Ann (Shaklee) Karns in 1970 when he was 52 and a father of 4 children with Laurette.

My purpose here is not to clarify or comment on what keeps some families together and tears others apart. I am concerned only in how life goes on regardless of the varieties and vicissitudes of marital and other personal relationships.

For reasons of no concern here, Earnest and Laurette went their separate ways sometime in the late 1960s. Earnest brought his 4 children with her to his 2nd marriage with Mary Ann Karns, a divorcee with 4 children who on average appear to have been somewhat older than his children, and they raised their combined family of 8 children together. After Earnest's death in 1999, Mary Ann remarried, and her 3rd husband would also figure in the lives of her Hoberecht step-children.

Laurette's life also went on. In 1971, she remarried Don Martin Claunch (1937-1991), a man her age, and she had a 5th child with him. Claunch had previously married in 1956, when 19, to a woman who was then 22.

Laurette Helene Heger (1937-2015)While Earnest Hoberecht strikes me as an interesting character, more interesting to me -- as an observer of the human condition -- is his wife cum ex-wife Laurette Helene Heger -- who later in her life would write an account of her homeland, centering on Saigon in French Indo-China, during the Pacific War. Available public documents and news reports generally agree on such facts as they include, but they leave the back stories either untold or out of focus. Laurette Helene Heger was born in Saigon in French Indo-China on 10 August 1937 to Marcel and Antonin Champon Heger, according to an obituary (see image to right). Marcel Heger, her father was of Swiss nationality, and her mother, Antonin Champon, was the daughter of a French father and Vietnamese woman. Laurette married the UPI journalist Earnest Hoberecht in New Delhi on 6 May 1959. She traveled to the United States from New Delhi via France on passport that indenfied her as French. Her obituary states that "During the French Indochina war [1946-1954], Laurette was sent to Europe to live with relatives, including a year at boarding school in Thonon-les-Baines, France" and later lived in Paris while attending a dressmaking school. 1959 marriage and visit to OklahomaLaurette was 21 when she married Hoberecht, and at 41 he was twice her age. He was also 20 years into a career that by then had made his by-line known all over the world of English-language reportage on Asia. An Immigration and Naturalization Service admission card (image to right) shows "Heger Laurette H." arriving in New York on 30 May 1959 on an Air France flight she boarded in Oiry, France, with a visa issued on 5 May 1959 in New Delhi, India. The card states that she was born in Saigon on 10 August 1937, permanently resided in "Tokio Japan", and her address in the United States would be "Watonga Okla." The "Nationality (Citizenship)" box says "French". I would guess that Laurette's family name on the admission card is Heger rather than Hoberecht because she entered the United States on a passport obtained before she was married. The visa was issued the day before she her marriage. 1962-1963 naturalization in TexasA "Petition for Naturalization" (see image to right) shows that "Laurette Helene Hoberecht (nee Heger)", then residing in Watonga, Blain County, Oklahoma, filed the petition at the District Court of the United States in Houston, Texas, on or about 21 January 1963. She took and signed an "oath of allegiance" was was thereby granted a certificate [of citizenship] on 25 January 1983. Her naturalization was linked with a "lawful admission for permanent residence" to the United States when entering America in Honolulu, Hawaii, on 21 December 1962. The naturalization petition states that Laurette was born in Saigon in French Indo-China and that she was a "citizen, subject, or national" of "France". The petition says she has "two" children, and it lists the names and birthdates a daughter Antonia Grace Hoberecht, and a son Earnest Hoberecht III, both born in Yokohama according to the petition. Laurette Helene Heger's obituary, however, says 3 of the 4 children she had with Earnest Hoberecht were born in Tokyo before they moved in 1966 to his hometown in Watonga, where their youngest child was born. If the obituary is correct, the 3rd child was born between 1963 and 1966 when the couple was again in Japan -- if they ever actually left. The "return" to the United states in late 1962 and early 1963 may have been contrived to facilitate Laurette's naturalization. December 1966 return to OklahomaIn fact, a newspaper article (see image to right) reports that the Hoberechts arrived at Will Rodgers World Airport in Oklahoma City on Saturday, 17 December 1966, with the intention of remaining in Oklahoma, where Earnest Hoberecht was born and raised. The photograph shows 2 children -- Antonia Hoberecht and Earnie Hoberecht III -- and Hoberecht's father E.T. Hoberecht. The caption notes that Laurette and the youngest (3rd) child Nathalia had also arrived at the airport. Nathalia is said to be 2 years old, which suggests she was born around 1964. The caption describes Laurette, who was born in Saigon in 1937, as "French-born", but that was true only in the sense that Vietnam was then part of French Indo-China. 2015 obituaryA long obituary carried in Friday, 3 July 2015 edition of The Oklahoman, an Oklahoma City paper, reported that Laurette had a 5th child, a daughter, after marrying Don Claunch in 1971. Earnest Hoberecht's 1999 obituary (see above) reported that he met Mary Ann Shaklee Karns in 1969, and Mary Ann's 2017 obituary reports that they married in 1970. Both brought 4 children to their marriages. Nathalie Kitson's MyHeritage website states that Don Martin Claunch was born on 2 August 1937 in lexington, Oklahoma, and died in 1991. His wife was Laurette Helene Heger and their child's family name is now Anderson. Ghislaine Heger's MyHeritage website describes Don Claunch's "ex-wife" as "Laurette Hé:lè:ne" Heger" showing acute and grave acents in in Laurette's middle name. Their child is described as "Anderson (née Claunch)". Laurette seems to have given birth to the youngest of her 4 children with Earnest Hoberecht in 1967. It thus appears that she and Earnest separated and divorced sometime between 1967 and 1969. Laurette appears to have reverted to her natal family name after Claunch died in 1991. And she herself passed away on 22 June 2015 in Tulsa, Oklahoma. According to Laurette's obituary, her 5 children -- 4 with Hoberecht and 1 with Claunch -- appear to be as follows. Tony [Antonia] Hoberecht See Saigon Is Burning at the end of this article for a review of Laurette Heger's personal account of Vietnam and the rest of Southeast Asia during the Pacific War (1941-1945) and the Franco-Vietnam War (1946-1954). |

Mary Ann (Shaklee) (Karns) (Hoberecht) Thurston (1933-2017)Douglas Martin reported in his obituary for Earnest Hoberecht (see above) as follows. In 1969, he found himself sitting at a local lunch counter next to Mary Ann Shaklee Karns. They each had four children from a previous marriage, and they were married seven months later. She remembers contemplating having a home with eight children and telling him, "We should get the Medal of Honor for this." Mary Ann Shaklee was born on 2 June 1933 on a farm near Watonga in Blaine County, Oklahoma. She died on 9 October 2017 at age 84 and is buried at Watonga IOOF Cemetery in Watonga. Earnest Hoberecht was born in the same town on 1 January 1918 and was 15 years old when Mary Ann Shaklee was born, and he and his parents are also interred at Watonga IOOF Cemetery. An obituary for Mary Ann Shaklee Thurston (below) states that she married Dwayne Karns in June 1950 and they had 4 children. Then in 1970 she married Earnest Trevar Hoberecht of Watonga and "embraced his four small children into her life instilling in them her own love of music". Then on 7 April 2001 she married Fred Thurston and "his three children and eight grandchildren were added to Mary Ann's caring love." Mary Ann Shaklee's Find a Grave memorial shows her spouses as "Kennis Karns" [Kennis "Dwayne" Karns] (1931-2018 m. 1950), "Earnest Trevar Hoberecht" (1918-1999 m. 1970), and "Fredy Thurston" [Fredy "Fred" Thurston] (1938-2019 m. 2001). All three husbands are buried, as she is, in Watonga IOOF Cemetery, It thus appears that Earnest Hoberecht and Mary Ann Karns met in 1969 and married in 1970, both as divorcees who brought 4 children each to their 2nd marriage. Mary Ann married a 3rd time some 2 years after Hoberecht's death in 1999, and apparently she is buried as Thurston, who passed away 2 years after her, Mary Ann thus appears to have raised Hoberecht's 4 children with Laurette. The oldest, Tony, would have been around 10 when Mary Ann and Earnest married in 1970. The youngest, Shelley, who apparently was born in 1967, would have been about 3. The obituaries of Earnest Hoberecht (1999), Mary Ann Thurston (2017), and Fredy Thurston (2019) list all 4 of the Hoberecht children. Tony [Antonia] Hoberecht Laurette Helene Heger's obituary (see above) also lists her daughter with Don Claunch Diane (Claunch) Anderson Find a Grave memorialThe Find a Grave memorial for "Mary Ann Shaklee Thurston" has reproduced the following obituary from an unattributed source.

|

Saigon Is BurningIn 2006, Laurette Heger published the following personal account of Southeast Asia during the Pacific War (1941-1945) and the Franco-Vietnam War (1946-1954). Laurette Heger In the book, Heger describes herself as "one quarter Vietnamese, a quarter French and half Suisse." Though her father was Suisse, she appears to have been a national of France at the time she first traveled to the United States in 1959 and when she naturalized in 1963. Back cover promotionThe back cover blurb promotes the story like this. This is not just a dry recital of history. This story is told from a different angle, as the author recounts her youthful memoirs during the Japanese invasion of Southeast Asia between 1940 and 1945. As a child, she observed first-hand the Japanese invasion of Vietnam, then a French Colony, and watched the Japanese efforts to conquer that part of the world while France, having been invaded by Nazi Germany, was unable to offer its help. Heger recalls the downfall of the French colonial regime, the rise of the Viet Minh, the independence of Vietnam, and the beginning of the first French-Indochina War that preceded the involvement of the United States. But this story moves to a deeper personal level, as one family attempts to live a traditional French life in the tropics while dealing with the horror and destruction of war in their private lives. The problem with all book blurbs is that -- like newspaper and magazine headlines and journal abstracts -- unless they are well written, they are likely to select and generalize in ways that misrepresent the book or article, or otherwise mislead people who don't take the time to closely and critically read the publication. Heger's book does not, in fact, relate the history of World War II in French Indochina or in postwar Vietnam quite like the back cover blurb. However, like most writers of personal accounts about events that occurred during their childhood and youth, Heger -- nearly half a century after she left Vietnam -- cooked parts of her story in hindsight, relating facts and misinformation she learned much later in her life, while relying on incomplete or faulty memory. Such faults are not unique to Saigon Is Burning, but characterize all autobiographies and memoirs. I write a lot about my own past, and constantly encounter problems sorting out my own memories with the recollections of others, and what I discover through library and other research about the times, places, and events that I choose -- very selectively, and for my own reasons -- to chronicle or comment on in publi. Laurette Heger was born in Saigon in 1937, and I was born in San Francisco in 1941. It takes little imagination to realize that while we were both children with two parents, our we and our families lived very different lives. I severed in the U.S. Army as a medic and medical laboratory technician from 1963-1966. The last 9 months or so of my enlistment was served at a U.S. Army general hospital I helped set up in Yokohama, Japan, in December 1965 for the express purpose of treating wounded, injured, and sick soldiers sent to the hospital from Vietnam. RESUME While I never stepped foot in Vietnam, Vietnam stepped foot in me in the form of the stories told by the soldiers, journalists, and others I met or read who had been there. And as an academic and journalist who specialized in Asian studies, I have made it a point to investigate the past in ways that help me grasp the sort of nuances that defy simple generalizations and judgments. (For details, see Kishine Barracks and the 106th General Hospital: Life and death in the Vietnam War medical communications zone in Japan). Laurette Heger seems to have lived in Japan for about 7 years, from shortly after she married Earnest Hoberecht in 1959 to 1966, when the family permanently moved to the United States. And she appears to have been living in Japan during the time I was there, from December 1965 to October 1966, and , and returned to America a couple of months after I returned in October 1966 at the end of my enlistment. RESUME Kishine Barracks: lleAmerican and other soldiers wounded battle or injured wounde If I were teaching a history course, I would ask my students to itemize everything in this blurb that strikes them as wrong, misleading, or otherwise odd. Or I would ask them to comment on the highlighted passages."the Japanese invasion of Southeast Asia between 1940 and 1945"Why would Japan -- how could Japan -- spend 5 or 6 years invading such a large sweep of real estate as Southeast Asia? Japan did not invade Southeast Asia "between 1940 and 1945". Its invasions of some countries lasted only a few days or weeks. All invasions resulted in gaining control within a few months. Fighting in some territories continued throughout the war, and Japan lost a number of territories during the war. "the Japanese invasion of Vietnam""France . . . was unable to offer its help""Vietnam" as such did not then exist. French Indochina consisted of several "protectorates" including Tonkin, Annam, and Chochinchina, which later became Vietnam. France capitulated to Germany when invaded and partly occupied in 1940. France did not cease to exist as a state but continued to function through a government established in Vichy, which accepted Germany's demands. Overseas missions continued to function, and French colonial officials in Indochina generally followed directives from the Vichy government. After France submitted to Germany, Japan forced France to aid and abet its desire to close French Indochina's northern borders with China. In 1937-1938, Japan had militarily occupied parts of China, and in 1940 it facilitated the creation of a Chinese government that cooperated with Japan. Japan no longer recognized the government of the Republic of China, which was operating in exile out of Chungking (Chongqing). Japan wanted to block the movement of munitions and other supplies to ROC that were moving by railway from Haiphong in Tonkin, via Hanoi to Kunming in Yunnan, and from there to Chungking. Japan's "invasion" of Tonkin came about when Japanese military forces jumped the gun on a time table for the establishment of Japanese military bases France had already agreed to accept. Sporadic hostilities were exchanged between 22-26 September 1940, and Japan had its way. But mindful of diplomatic protocol, on 5 October 1940 Japan formally apologized for its breech of French Indochina's borders, returned towns it had occupied, and released captured soldiers. While all this was going on, Japanese and Italian diplomats in Berlin were negotiating terms in a Tripartite Pact with Germany, which was signed on 27 September 1940 -- the day after the end of the fighting in Tonkin. The pact, though a mutual defense agreement, did not oblige the party states to fight a common war. Europe and Greater East Asia were too far apart to matter in terms of shared geopolitical or economic interests. The pact in effect allowed Japan a free hand in Greater East Asia. France, having submitted to Germany, was nominally in Germany's camp. France, thinking that Germany might help it keep Japan at bay in French Indochina, asked Germany to mediate with Japan on it's behalf, but Germany declined. The whole point of the alliance between Germany and Japan was that neither state would interfere in the affairs of the other state. The other side of this coin meant that Japan was not bound to adopt Germany's policies regarding, say, Jews, hence Japan's leniency regarding the accommodation of Jewish refugees in its spheres of influence. French officials in Indochina with nationalist sentiments were probably not elated about the prospects of serving the Vichy government. But they lacked the political capacity and material resources to ignore the Vichy government and unilaterally fight Japan, which was bent on isolating Chungking. Such as it was, French Indochina's resistance to Japan's incursions in September 1940 was little more than a gesture on the part of a waning European power clinging to Asian colonies Japan was ideologically committed to liberate in the name of its own Asianism, centered on its own national interests. Vichy France quickly got used to accommodating Japanese military bases and other interests in Indochina. From the perspective of Japan's alliance with Germany and Italy, Japan did not "occupy" French Indochina so much as fulfill its obligation to ensure that the territory submitted to the cause of the Tripartite Alliance -- which recognized the independence of Japan's interests in Greater East Asia. One can imagine a future in which, if the Axis Powers had had their way in their respective spheres, the German-Italian and Japanese Empires would have clashed somewhere in the twain between Europe and Asia. In preparation for its planned invasions of colonialized Southeast Asian countries, with the aim of liberating and incorporating them into the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, Japan began to build military bases and deploy forces to the southern protectorates of French Indochina. Thailand, an independent country to the west of French Indochina, also took advantage of France's weakened position and reclaimed parts of French Indochina that had once belonged to it. Japan later enlisted Thailand's help in overrunning and liberating Burma, in return for control of some bordering territories, and membership in the growing Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. When the Allied Powers liberated France on 9 March 1945, the Vichy government fell. France regained its status as a fully sovereign state and member of the Allied Powers, which had already forced Italy to surrender and were now bearing down on Germany and Japan. With the liberation of France in Europe, Japan lost the ability to control French Indochina through the facade of diplomatic relations with Vichy France. It also faced the likelihood that French garrisons and agencies in Indochina would rise up against Japan. Japan thus took the initiative in capturing French garrisons and taking over French colonial offices throughout Indochina. Between 9 March to 15 May 1945, Japan divided French Indochina into three nominally independent states that were immediately counted as members of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere -- the Empire of Vietnam (11 March 1945), the Kingdom of Cambodia (11 March 1945), and the Kingdom of Luang Phrabang [Laos] (8 April 1945). Cambodia and Luang Phrabang were set up as constitutional monarchies. Vietnam was under the control of Viet Minh led by Ho Chi Minh. French officials in Vietnam began to be replaced by Vietnamese who had been trained to fill administrative posts. The fuller story of Japan's invasion of Southeast Asia is many times more complicated than the above overview. The point is -- there was no "Japanese invasion of Vietnam". Such as they were, Japan's initial aggressions were mostly in the form of strong-armed diplomacy, and its later aggressions were well within the range of tactics that are common in times of war. "the beginning of the first French-Indochina War that preceded the involvement of the United States"As an major Allied Power in the Pacific Theater of World War II, the United States became involved in the postwar disposition of French Indochina as soon as postwar settlements became an issue of the Allied Powers during the Pacific War (1941-1945). The 1st (French) chapter of the Indochina War (1946-1954) also involved the United States. In fact, there probably would not have been a 1st or 2nd Indochina War if the United States had opposed the restoration of French control over Indochina. Ho Chi Minh borrowed phrases from the opening of America's Declaration of Independence when declaring the independence of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam on 2 September 1945, the day Japan and the Allied Powers signed the general surrender in Tokyo. The Republic of China, an Allied Power, then accepted Japan's surrender of French Indochina north of the 16th parallel (Tonkin, which included Hanoi, and part of Annam) and Great Britain accepted Japan's surrender south of the 16 parallel (Chochinchina, which included Saigon, and part of Annam). Roosevelt had opposed the restoration of colonial regimes after the Pacific War, but he died before the war ended. Truman, his successor, was concerned about the spread of communism, and he favored Eurocentric policies when it came to settlements in countries and territories Japan had occupied during the war. Truman therefore supported France's insistence that its military forces relieve both British and Chinese forces in the two occupation zones and thereby restore its colonial sovereignty over Indochina. France refused to recognize an independent Vietnam outside its sovereign embrace, and many other problems developed as the British and Chinese occupation zones, where Britain and ROC had their own agendas. Ho Chi Minh, in a telegram to Truman dated 28 February 1946, pled for his help in securing recognition of Vietnam as an independent sovereign state. His letter survives in U.S. government archives. Ho never heard from Truman. During the 1st Indochina War, the United states spiritually, materially, and even militarily aided French forces in their attempt to wrestle control of the north from its Viet Minh (�z�� Viet-Nam doc-lap dong-minh �z�������� "Vietnam Independence League") defenders, founded by Ho Chi Minh on 19 May 1941 and led by Vo Nguyen Giap (1911-2013). |