|

|

1962 Collins hardcover (UK)

|

|

|

|

1962 World hardcover (US)

|

|

|

|

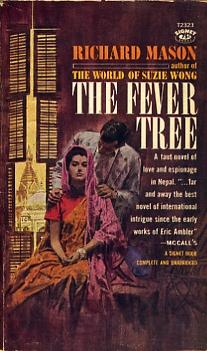

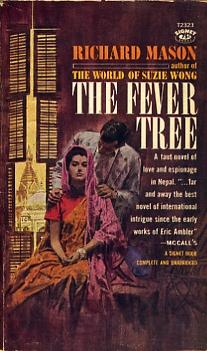

1963 Signet paperback (US)

|

|

|

|

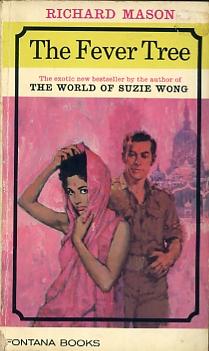

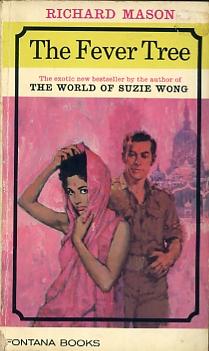

1964 Fontana paperback (UK)

|

|

Richard Mason

The Fever Tree

Hardcover editions

London: Collins, 1962

320 pages, hardcover

Cleveland: The World Publishing Company, 1962

316 pages, hardcover

Paperback editions

New York: Signet Books, 1963

285 pages, paperback (T2323)

London: Fontana Books (Collins), 1964

255 pages, paperback (988)

American and British blurbs

The blurb on the fly of the Signet paperback in the United States introduces the woman first.

LAKSHMI KAPOOR is a lovely, lonely young matron who no longer amuses her wealthy husband. He has replaced her with a series of mistresses, and Lakshmi has decided to do something about her meaningless life . . . to look for adventure, romance, perhaps someone different. . . .

MAJOR BIRKETT is an English bachelor who poses as a writer of travel books. He is actually in India on a dangerous undercover mission. Birkett travels light and wants to keep it that way -- no responsibilities, no ties, no woman to answer to after the night is over. . . .

They meet in a bar in Delhi. Laksmiri dares to flit; Birkett decides to seduce. But neither intends to fall in love. Love, for them, is much too dangerous.

The Fontana paperback in Britain begins with the home boy hero.

Birkett, an enemy of the world he knows because of what he thinks it has withheld from him, accepts a commission to procure a political murder : he also accepts the adoration of an Indian girl to whose gentle inexperience he represents the perfection of manhood. However, these two commitments prove to be incompatible : Birkett is made aware that love, which he had taken to be a weakness, can have a formidable strength : and the drama closes upon him desperately seeking refuge not only from his enemies but his own past, by way of the inhospitable splendours of the high Himalayas.

Pig-sticking names

The Fever Tree unfolds in the 1950s, after British India was split in 1947 into two countries, India with a Hindu majority, and East Pakistan and West Pakistan (Pakistan and Bangladesh since 1971) with a Muslim majority.

Mason, who spent a lot of time in South Asia during World War II, makes this observation through Birkett's eyes as Birkett kills time in the New Delhi Club (pages 5-6).

Birkett sipped the small whisky. His gaze fell on the mahogany honour-board behind the bar, listing the Club presidents in letters of gold. They went back over thirty years. Fotheringay, Whittington-Smith, Sir R. Boland, Bell-Carter . . . You could see the hands holding the whisky-sodas, the moustaches bristling under the sun-helmets as they set off for polo or sticking pigs. You knew from the names they had all been pig-stickers: you only wondered that there had been enough pigs to go around. Smedley-Cox, Atheleston . . . And so on until, with Sir Joshua Hindcliffe, 1947, the pig-sticking names came to a resounding end. And then: Sen, Desani, Muckerjee, Singh . . .

Yes, a decade ago, Birkett thought, the only Indians you'd have seen in this place were the waiters in compulsory white gloves to conceal the grey hands. And now the few British who came here fell over themselves to behave like Indians while the Indians behaved more like the British than the British themselves.

Under the old fever tree . . .

Boy and girl do meet in the club but Birkett has no time for distractions, for he is on a rendezvous with destiny. Leaving the club, and driving off in his hired car, he feels again like the cheetah he had seen under a fever tree in Africa (pages 10-11, Fontana edition).

He felt the first touch of exhilaration. He was on the job again. The cheetah was off in a new prowl.

He drove swiftly. On either side of the road the parched stony plain lay deserted under the moon. And he remembered the African plain, and the cheetah sitting alone under the tree in the hot African afternoon. And then the sun going down, and the cheetah lazily rising, and yawning -- and a sudden uneasiness running like a shiver through the great herds of wild creatures that filled the plain: the fat zebra interrupting their grazing with anxious backward looks, the bearded wildebeest restlessly tossing their heads, the wagging metronome tails of the Thomson's gazelle suddenly missing the beat. And then the first stir of panic, and the dust rising from the hoofs as the herd moved away from the danger they had felt but not yet seen -- from the lone cheetah whose yawn had spread fear through them like a contagion. And the cheetah sensuously stretching and yawning again, and strolling out from under the tree; trim-waisted, self-sufficient, and serenely alone, the strongest and swiftest animal on the lain. The perfect animal-machine.

. . . it snowed

Some 250 pages later, this highly readable story ends with the observation that "It began to snow."

|