How to read pulp fiction

The real hero of "Manchu Terror"

By William Wetherall

First posted 10 May 2006

Last updated 21 July 2024

|

|

|

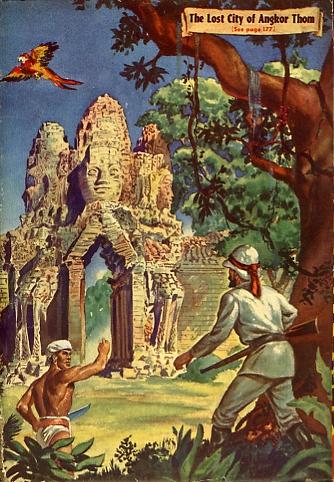

Front and back of Mammoth Adventure, July 1946 |

|

William P. McGivern

"Manchu Terror"

Mammoth Adventure

Vol. 1, No. 1 (July 1946)

The face on the cover is humorous, hideous, or simply human -- depending on how you look at it -- and on how much you know about the man, his smile, and the pistol.

The face is of a character in the featured story, "Manchu Terror", by William P. McGivern (1922-1982), one of many writers who cranked out short stories and novels for the pulp magazines and paperbacks that filled American newsstands and drugstore racks before but especially after World War II. The story is reprinted in Tony Goodstone's 1970 anthology, The Pulps (pages 24-29), which is reviewed in Resources.

The images shown here are from the cover of the original magazine. Below the title of the story is this teaser.

Anyone who could remain calm when faced with Pistol Packin' Papa's weapon must have nerves of steel -- and a heart to go with them . . . !

Pistol Packin' Papa

The story is told by the self-styled hero, whose name we never know. It begins crisp and hard (page 24).

|

He was quite a character. We called him Pistol Packin' Papa, which isn't particularly clever or bright, but newspapermen in China aren't clever or bright, or they wouldn't be there in the first place. He hung around a little cafe called Yang's that we had made sort of unofficial Headquarters for the press crowd stationed in Shanghai. It was a beat-up, little joint, usually crowded, and always noisy, half of it coming from the crowd, and the other, and less bearable half, coming from the three-piece orchestra, whose members seemed to think that sheer noise would compensate any musical deficiencies. Pistol Packin' Papa was a fat, ragged, ancient Chinaman, with tiny eyes, set in shiny folds of flesh, a scrawny mustache and just about the easiest and most profitable racket in Shanghai. He was a beggar but he had an angle. A damn good angle. |

Bartlett and Yang

The hero is sitting at a greasy table in Yang's with Bartlett, a wire service reporter who is new to Shanghai. The hero gets Papa to play a gag on Bartlett, as part of his initiation to the city, after which the plot thickens (page 25).

|

We forgot about Papa and started talking shop. The situation for newspapermen in Shanghai then was worse than it had been during the war. Our copy was getting out all right, but censorship was ridiculously strict. There were a lot of Japs left in Shanghai, a lot of Russians, a lot of communists, and a few Fascist Chinese organizations and trying to play the angles in that international mess, was enough to drive a guy nuts. We were working on another drink when Yang came over to say hellow. Yang was a bland, neatly built Chinese, with pleasant friendly eyes. He wore European clothes and he always dressed sharply. I knew he was a very square guy. During the war he'd kept his place open and provided a good time for Jap officers. But how many of them got cyanide in their drinks, and how much information was collected from their drunken ramblings and forwarded to Chinese Headquarters, was something probably only Yang knew. And he never talked about it. |

Yang has a paper that must be delivered to a certain representative of "Chiang-Kai Shek" (sic). The hero accepts an envelope and agrees to take care of it. Yang is then found murdered.

The Eurasian

A "fussy little inspector" who "sounded like he'd been reading Charlie Chang" but who "looked pretty smart" suggested they might learn more by letting Yang's cafe continue to operate. While hanging out there, the hero is approached by a girl who rests a hand on his shoulder and has a smile just for him. This is how he describes her (page 27).

She was Eurasian. Probably Russian and Chinese. Her skin was pale and flawless and there was enough Mongol in her blood to give her features an interesting look without making them hea-vy and lifeless. She wore a tailored white suit and her bare feet were thrust into small red sandals. Her hair was dark and her eyes would be either green or blue depending on the light. Or on how she was feeling."

She is looking for Yang's friends. Perhaps the hero could help her. Would he meet in a room upstairs in ten minutes? He goes at the appointed time and finds the room dark. There is an illustration of the scene that follows with a caption that paraphrases the story: "When I turned on the light I saw her . . . She had been bound by somebody who knew his business."

"They didn't want to kill me," the girl tells the hero. "They were looking for the paper Yang was to give me."

Bartlett steps out of the closet with a drawn gun and forces the hero to give the envelope to the woman, who stuffs it down the front of her dress and beats it. The hero struggles with Bartlett and, in self-defense, strangles him. The Shanghai division of the FBI had known about him but is mum about his death. They don't want people asking questions.

Pistol Packin' Papa sees the girl running out of Yang's place, draws his Boxer Rebellion vintage weapon on her, and says "stick-em-up, give me money." She drops dead from fright. Papa's only aim was to play on her the same "Chinese bandit" gag he had played on Bartlett, at the hero's request, earlier in the story.

Never mind that the girl was working with Bartlett and had baited the hero into a deadly trap to get the envelope -- Pistol Packin' Papa cannot bear the thought that he has caused the death of another human being. McGivern's ending wraps back to the opening.

|

Pistol Packin' Papa isn't a character any more. He threw his gun away and he was so badly frightened by the whole affair that he went to work for a living. I saw him the other day pulling a rickshaw and he looked thoroughly unhappy. He's lost a lot of weight. |

What's in a stereotype

You can't get any pulpier than this. The story is highly structured, as any good story must be. Some of the narrative and dialog is corny by today's standards. But McGivern knew how to pack a lot of suspense, surprise, and human interest into just a few pages.

Stereotype busters would have a field day with the "Chinaman" on the cover of Mammoth Adventure and some of McGivern's verbal portraits. They could dwell on the "Orientalist" implications of the cover art and the roles assigned the Chinese characters to make the presumably American reporter a hero.

The surface images, though, are deceptive. Readers who trip over the "stereotypes" risk not noticing that the most sympathetic character in the story, who unwittingly saved China in 1946, was not the pro-nationalist reporter with a weakness for Eurasian women, but a street-smart "Chinaman" with a sense of humor and a heart.