Life in the Army

Before, during, and after Vietnam

1964 column with 2017 afterword

By Pfc. Bill Wetherall

|

1. Thu 29 Oct 1964 |

2. Fri 30 Oct 1964 |

3. Mon 2 Nov 1964 |

4. Fri 6 Nov 1964 |

|

|

|||

|

5. Mon 9 Nov 1964 |

6. Tue 10 Nov 1964 |

7. Wed 11 Nov 1964 |

8. Thu 12 Nov 1964 |

|

|

|||

|

9. Mon 16 Nov 1964 |

10. Tue 17 Nov 1964 |

11. Wed 18 Nov 1964 |

12. Thu 19 Nov 1964 |

|

|

|||

|

13. Mon 23 Nov 1964 |

14. Tue 24 Nov 1964 |

15. Thu 26 Nov 1964 |

16. Thu 26 Nov 1964 |

|

|

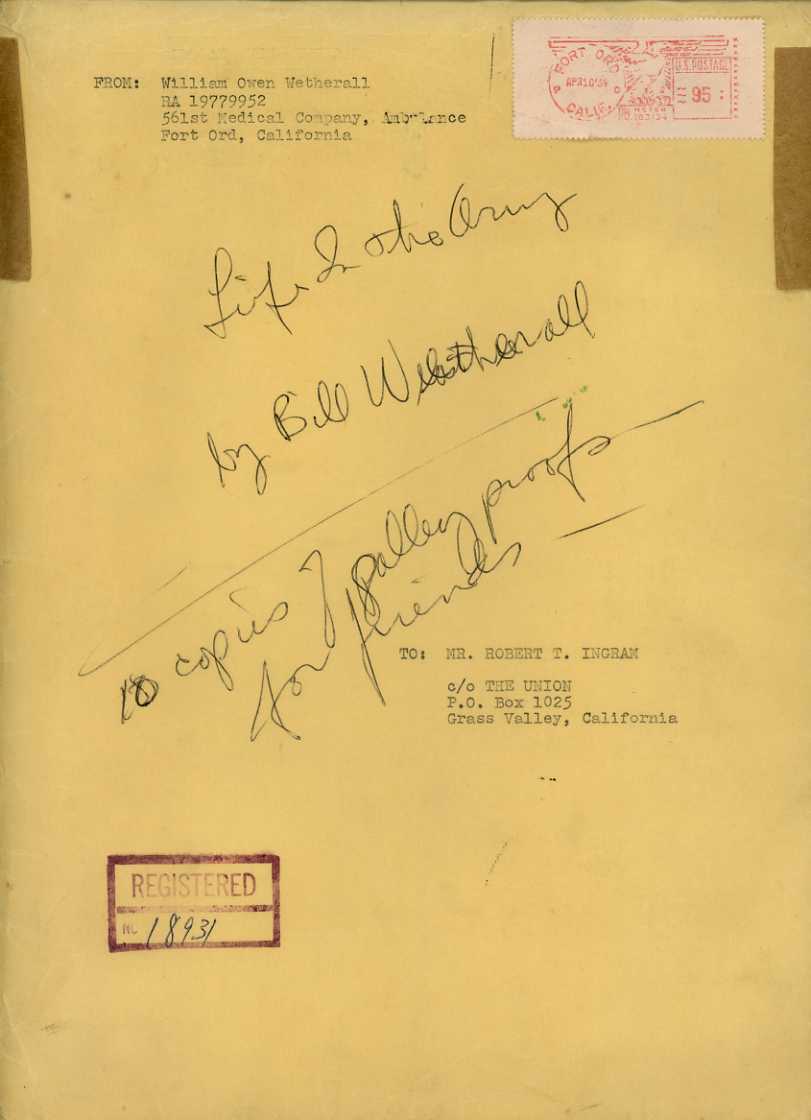

|||

Before Vietnam (Foreword)In 1964, The Union, then an evening paper published in Grass Valley, my hometown, ran a column I started writing when I was 22 going on 23 called Life in the Army. I wrote the column while assigned to the 561st Medicial Ambulance Company at Fort Ord, about 250 miles from Grass Valley, or the better part of a day by a mix of local and express Greyhound busses via Monterey, San Francisco, and Sacramento. The column ran in 16 installments from 29 October to 26 November 1964. The installments, compiled from 6 manuscripts representing 6 chapters, vary in length but average about 1500 words. The writing ranges from not bad to horrible. Some of the comments I made in my correspondence to the editor, concerning my motives and ambitions as a chronicler of my military life, show me to be a very naive, presumptuous, and unabashedly confident young man, who totally believed he had story to tell and was desperate to see it in print. First manuscript rejectedEarly in 1964 I submitted a manuscript to Robert Ingram, then the president and editor of The Union, which the previous year had published my long diatribe on Nevada County Education and Culture. I had long since forgotten about the column until 1998, when Robert Lobecker, a high school and college classmate and friend, sent a complete set of clippings to me at my Grass Valley address, which my parents held for me until my spring visit the following year. My father mentioned that he still had a copy of the galleys in a file somewhere, but I did not see it then. I recalled that he had been involved in helping the editor make some timely decisions, regarding personal remarks I had made in a couple of the installments, as they were going to press, as communications between me and the editor were limited to postal communications. Then a couple of years or so before my father passed away, which was in 2013, he told me that he had received a phone call from Jeannie Ingram, the widow of Robert Peter Ingram (1926-1997), the third and last Ingram to manage and edit The Union. She had found an envelope with my name on it among her husband's papers, and wondered if I might like it. My father assumed I would, and one day she brought it to him. I would not see it, though, until 2015, when my brother, who had brought some of my father's papers to Honolulu, forwarded it to me. The envelope kept first by Robert and then by Peter Ingram, as shown to the right, is postmarked Fort Ord, California, 10 April 1964. I had registered the mail, and the back shows Fort Ord franks for 10 April and a Grass Valley frank for 11 April 1964. The envelope is addressed to Robert T. Ingram, who apparently used it as a file for the manuscripts and letter I had sent him in the envelope, as well as several two other manuscripts and letters from me dated as early as 30 March and as late as 15 October 1964 -- just 2 weeks before the publication of the 1st installment on 29 October 1964. |

Contents of envelope

The envelope from the Ingrams contained the following letters and manuscripts.

30 March 1964 Long, rambling, 3-page single-spaced letter. In the letter, I thank Robert Ingram for critical comments he made regarding an earlier manuscript which he rejected and returned via registered mail. I acknowlege his critical points but make a counter proposal for a 6-part article I wished to title "Life in the Army". The proposal includes titles for the first 5 parts. I corrected the title for Part 5 by hand. I left the title of Part 6 "undecided" but I described what I intended to cover. I enclosed the manuscripts for Parts 1 and 2 with this letter.

|

Since receiving your letters two weeks ago I have written the first two parts. I believe I can finish the series up to the end of April. We are scheduled to go on a field problem south of the Needles area (called Desert Strike) during the month of May. It is unlikely that I will be able to do much work of this nature in the field. As it is I am spending every single moment on the series in an effort to finish before I go to the field. It requires that I complete one three thousand word paper a week, which seems easy enough except when you consider the conditions I must work under, namely, sitting on the edge of my bunk to type, my desk being nothing more than a couple of foot lockers stacked up on one another. And never except be it on a weekend do I have more than two hours at a time to work. [ Omitted ] I must warn you that I am in a STRAC [Strategic Army Corps] unit, which means that I can be in combat tomorrow. We are constantly having alerts, which further means that even though I am in garrison, I could be so busy in the orderly room typing official documents that I would have but little if no time to work on the articles. As things look now I should be able to complete them. However, please realize that something could happen that would forbid me to. [ Omitted ] By the way, I've got my own typewriter now, a Smith Corona Sterling. Though it's a portable, it's got a standard (large) keyboard which allows me to really stretch my fingers. |

10 April 1964 1-page single-spaced cover letter for Parts 3 and 4. I claim that I will have adequate time to complete Parts 5 and 6 before leaving Fort Ord for a field exercise in May -- alluding to what I described in the first letter as "a field problem south of the Needles area (called Desert Strike)". In this letter I provide the titles for Parts 5 and 6. I also ask Ingram to "Please allow me the privilege of seeing the galley proofs prior to running the parts."

3 May 1964 2-1/2-page cover letter for Chapters 5 and 6. I explain that Chapter 6, unlike the other chapters, has three parts -- and I provide not only titles for each part, but also titles for the subheads of each part. I explain that I had decided to call the 6 parts "chapters" in order to allow me to divide the 6th chapter into 3 parts. I provide my temporary military address in Needles, California. I also apologize for not having been able to register the mail enclosing this letter and Chapters 5 and 6. I write that Chapter 6 was "hurridly assembled" -- and apparently I fleshed it out with passages from the rejected manuscript. I may have missed an opportunity to mail it at Fort Ord and dropped it in a mailbox enroute to Needles, or mailed it from the camp we set up in the desert. In this letter, I made the following remarks regarding why, at the end of the April, on the eve of leaving for Needles, "I was wondering if Chapter Six would EVER be written."

|

My problem was not a small one. Believe me when I say I have material for a lengthy book. Chapter Six just about HAD TO BE a catch all, at least for THIS author it had to be a catch all. Not to mention the fact that during the past three weeks I have had to write a UNIT HISTORY for the 561st Medical Company, which turned out to be a project and a half, twenty-five pages including an appendix and bibliography. And now it looks as though I will become the 58th Medical Battalion Historian, and will perhaps begin next fall compiling a Battalion history and a history of all units organic to the 58th Medical Battalion. Writing war history during the day and writing about Life in the Army in the evening and on weekends has just about done me in. During the day, as I research for the Unit History, I read of the medical support our unit and other units gave to the allied forces in Europe and to the UN forces in Korea, of the blood and guts strung from the entrances of the surgical tents to the exits, of the dead piled in the latrines, and the medics and ambulances that became the principal targets for the Red Chinese, and in the evening I am to write something that is beautiful and inspiring and continuous. I am to write Life in the Army in twenty-five words or less, when perhaps 25 million words are required, and when perhaps DEATH in the Army is a more appropriate title. |

26 July 1964 5-page letter itemizing corrections to Columns 16-20 of galleys, representing Chapter 4. This letter ends with the following request for 10 copies of the galleys to send friends.

|

By the way, a number of friends of mine (that are spread out all over the country) have requested copies of LIFE IN THE ARMY. I have been trying to figure out how to satisfy these requests. I would need about 10 copies. I suppose the best way to do this is to ask you for ten copies of each of the galleys AFTER corrections have been made. This would certaintly [sic = certainly] be easier and cheaper than my buying ten copies of each edition in which a fraction of a chapter appears. I would be willing to pay you for the service as these friends are my better critiques and I am anxious to oblige their requests. Please let me know if this suggestion suits you and the charges for the copies, or perhaps you can offer a cheaper alternative. |

Undated (circa September 1964) 4-page letter written back-to-back on 2 sheets of lined paper torn from a spiral notebook. Pages 1 and 2 are missing. Pages 3 and 4 show corrections for Columns 21 and 22 of galleys. This letter ends with this remark about my military activities.

|

Am being special dutied for two months to act as the HERALD for the Battalion. My job will be to compile a unit history for official publication, and to design and justify the design for a unit Crest or Coat of Arms. Not especially interesting subject matter, or for that matter desireable subject matter, but at least I'll be applying a little grammer [sic = grammar] rather than "look busy at the motor pool" for eight hours a day.

I have no memory of the image of the crest I designed. The above approval came two years into the Vietnam War over a year after the 58th Medical Battalion was deployed in the Vietnam. I recall deploying serpents, as they are the essential parts of the caduceus -- the symbol the U.S. Army adopted for its medical corps -- which features two snakes coiled around a winged staff. I believe I also recommended a red cross for the reasons given, as they appealed to my personal justification of my own in-service conscientious objector (CO) status, which I had obtained by application at the time time I was writing the history for the 561st Medical Company, my primary affiliation as a medic and ambulance driver. The purple link with blood may also have been from my notes, as red on purple is one of my favorite color -- the rest I cannot. as a symbol of medicineelements of and a cross, |

15 October 1964 7-page letter itemizing corrections for Columns 22-33 of galleys, representing Chapters 5 and 6. At the end of the letter, I reiterate my request for 10 copies of each chapter, preferrably in the form of falley proofs. I also request that, from this point, all correspondence regarding the column be sent to me in-care-of John Phelan, a high and college friend and classmate who lived in Pacific Grove, next door to Monterey.

Undated (nlt 30 March or 10 April) Original manuscripts of Part 1 (10 pages), Part 2 (9 pages), Part 3 (11 pages), and Part 4 (11 pages). The manuscripts for Chapters 5 and 6 are missing. The four surviving manuscripts are double-spaced typescript, loose leaf and paper-clipped. They are fairly clean but bear a few neat corrections in my hand. They also show some corrections and very light editing in another hand -- presumably Robert Ingram's, possibly Peter Ingram's. perhaps another copy editor's.

Editorial hands and galleys

Peter Ingram, like his father, had come up through the ranks doing everything related to the paper's publication, from newsgathering, writing, and editing to printing, distribution, subscriptions, and advertising sales. At the time my articles were being processed for publication, Peter was already doing a lot of the managerial editing, and it is possible that his father, while handling the correspondence with me, farmed out the grunt work to Peter if not a staff editor. My feeling, though, is that another editor, unless ordered to go easy, would have had a heavier hand.

My father was also involved in some of the last-minute editing in preparation for putting an installment to bed. He told me Robert Ingram had directly approached him regarding the need to make some changes concerning personal remarks which I had made in the original manuscript, but which had not been flagged in the pre-galleys edit.

Among my father's papers I found one practically mint copy of the galley proofs. The proofs run 5 broadsheet pages consisting of 34 numbered columns at 8 columns per page, thus only two columns on the last page. They bear a few -- though very few -- light pencil corrections in my father's hand -- most of them concerning the problematic personal remarks.

Whatever Peter Ingram's involvement, if any, the envelope I mailed his father on 10 April 1964, which came back to me stuffed with most of my letters to his father, and most of my original manuscripts, ended up in Peter's files -- possibly simply because he had inherited his father's files.

Whatever the chain of custody, clearly my letters and manuscripts were treated personally. For had they been consigned to company files, I would not have them today.

Pacific Grove safe house

The request to route all mail related to Life in the Army to Pacific Grove comes with the following back story, which involves a bit of intrigue on my part.

I spent a lot of time with my high school and college friend and classmate John Phelan and his wife Irene on weekends, watching him rebuild a Model A, playing catch, sometimes baby sitting their infant son. The back story is that his home had become a sort of "safe house" for me.

That fall I had begun writing a whistle-blowing report on the medical battalion and ambulance company for which I had been writing unit histories. Unable to type the clean copy of a formal report on legal paper in the barracks, I got John's wife to introduce me to a local aquaitance, a professional typist, who banged out the report for a modest fee. I am fairly certain that I had already mailed the report by October 1964, possibly in September, but definitely after the Tonkin Gulf Incident in August. Possibly in November, I was called to the headquarters building at at Ft. Ord, where an officer -- I can't recall who, or his title or rank -- asked q few questions to confirm that I had written the report and my motives. In December I was transferred to the physical examination section of Fort Ord Army Hospital.

The orders orginated after the Adjuctant General, to whom I submitted the report, kicked the report down the chain of command to the higher command at Fort Ord for appropriate action. After being transferred to hospital duty, I was called before a number of officers to answer questions concerning statements I had made in my report. I never heard about it again. Friends in the battalion and company told me there had been a few changes in activities. However, I could not tell if the changes were on account of fallout from my report, or because the units had been alerted to possibility that they might be mobilzed for duty in Vietnam.

By the the end of the year, I was transferred from Fort Ord Army Hospital to the Sixth U.S. Army Medical Laboratory at Fort Baker, near Sausalito, for training as a laboratory technician. Early the following year, the ambulance company went to Vietnam. While in training at Fort Baker, I corresponded with a former bunkmate and fellow ambulance driver who went to Vietnam with the ambulance company, and with a French-speaking friend who was pulled out of the ambulance company and sent to Vietnam to work in prisoner-of-war interrogation. I still have their letters.

I worked on the battalion history at a desk in the office next to the office of the battalion commander, who sometimes had me ghost letters for him and even help his junior officers draft plans for field operations. I had full access to current battalion records. I also had the authority, over an officer's signature, to request copies of archived historical records. In the ambulance company, I had volunteered to help out in the orderly room and become the de facto company clerk, with access to personnel records. My typing and writing abilities got the attention of the company commander, who recommended me to the battalion commander, who also found himself short of clerical talent.

Some entries in personnel records struck me as odd, and the oddness became clear when I read the battalion and company mission statements on file at the battalion headquarters. I discovered that the battalion, and the ambulance company under the battalion's supervision, were taking shortcuts in training and engaging in activities that somewhat jeopardized their STRAC missions -- something I later learned was a common problem in peacetime armies that get lazy about training and cover up their laziness by fudging their records. The records reflected that ambulance drivers were pulling occasional duty on Fort Ord Army Hospital wards, which was required to maintain and improve their familiarity with basic nursing skills. But I couldn't find anyone in the company who had spent any time working on a ward. Ambulances and other field vehicles were supposed to be combat-ready, but they were being waxed and polished -- with gasoline no less (it being an open secret that a waxed vehicle would shine more if buffed with gasoline) -- according to spit-and-polish "looking STRAC" peacetime parade standards. Moreover, I learned that battalion and company officers and cadre were being informed in advance of STRAC alert drills intended to test the ability of the units to muster their personnel and be ready to pull out on a nearby railhead within 24 hours of notification.

The Union

The Union was then an evening newspaper. It began as the The Grass Valley Daily Union in 1864, at which time it was a truly local Grass Valley paper. The flag changed to The Daily Morning Union in 1904, The Morning Union in 1908, then to just The Union in 1945 when it became an evening paper.

Sometime after my articles appeared in 1963 and 1964, its masthead began billing it as "Founded in 1864 to Preserve The Union -- One and Inseparable." This political hype dates from no earlier than this, and no later than 1978 (based on a clipping of a front page feature titled "Parking area covers Chinese burial grounds?" (Tuesday, January 17, 1978, Vol. 113, No. 70, Price 15 cents). The Union has traditionally been a Republican paper, and Abraham Lincoln was a Republican.

A brief history of The Union, focusing on the Ingram family, would read as follows.

| 1864 | Grass Valley Daily Union founded 26 October. |

| 1866-1893 | Charles H. Mitchell becomes publisher. |

| 1882 | Thomas Ingram Sr. and family arrive in Grass Valley from Nevada in September. He works as pump man at Empire Mine. |

| 1885 | Thomas Ingram Jr. apprentices as printer at age 16. |

| 1893 | Grass-Valley-born William F. Prisk (1870-1962) becomes editor and publisher. Prisk runs the paper until about 1908 and retains ownership until 1946. |

| 1890s | Thomas Ingram Jr. joins Union staff. |

| 1903 | Moves on 30 July from the office and pressroom on southwest corner of Mill and Main streets to a building constructed expressly for The Union on 151 Mill Street, where the paper would be published and printed until 1978. |

| 1904 | Renamed The Daily Morning Union from 22 March. |

| 1906 | The paper is incorpated. |

| 1908 | Renamed The Morning Union from 7 August. Thomas Ingram assumes most managerial responsibilities. |

| 1928 | Thomas Ingram dies. Prisk hires Robert Ingram to replace him. |

| 1945 | Flag changes to just The Union as paper becomes evening paper from 18 June. |

| 1946 | Robert Ingram and Early Caddy buy out Prisk's interest in The Union. |

| 1965 | Robert Ingram retires. Peter Ingram takes over many managerial responsibilities. |

| 1968 | Nevada County Publishing Company buys The Union. Peter Ingram remains its editor and publisher for 7 years. |

| 1975 | Peter Ingram retires |

| 1978 | Relocates from 151 Mill Street to its present location at 464 Sutton Way in the Glenbrook Basin. |

| 1988 | Robert Ingram dies |

| 1997 | Peter Ingram dies |

Robert T. Ingram was the publisher of The Union at the time it ran "Life in the Army". His son, R. Peter Ingram, became the publisher the following year. The paper was bought by the Nevada City, and continued to be involved with The Union when his father sold his stock in The Union Publishing Col.

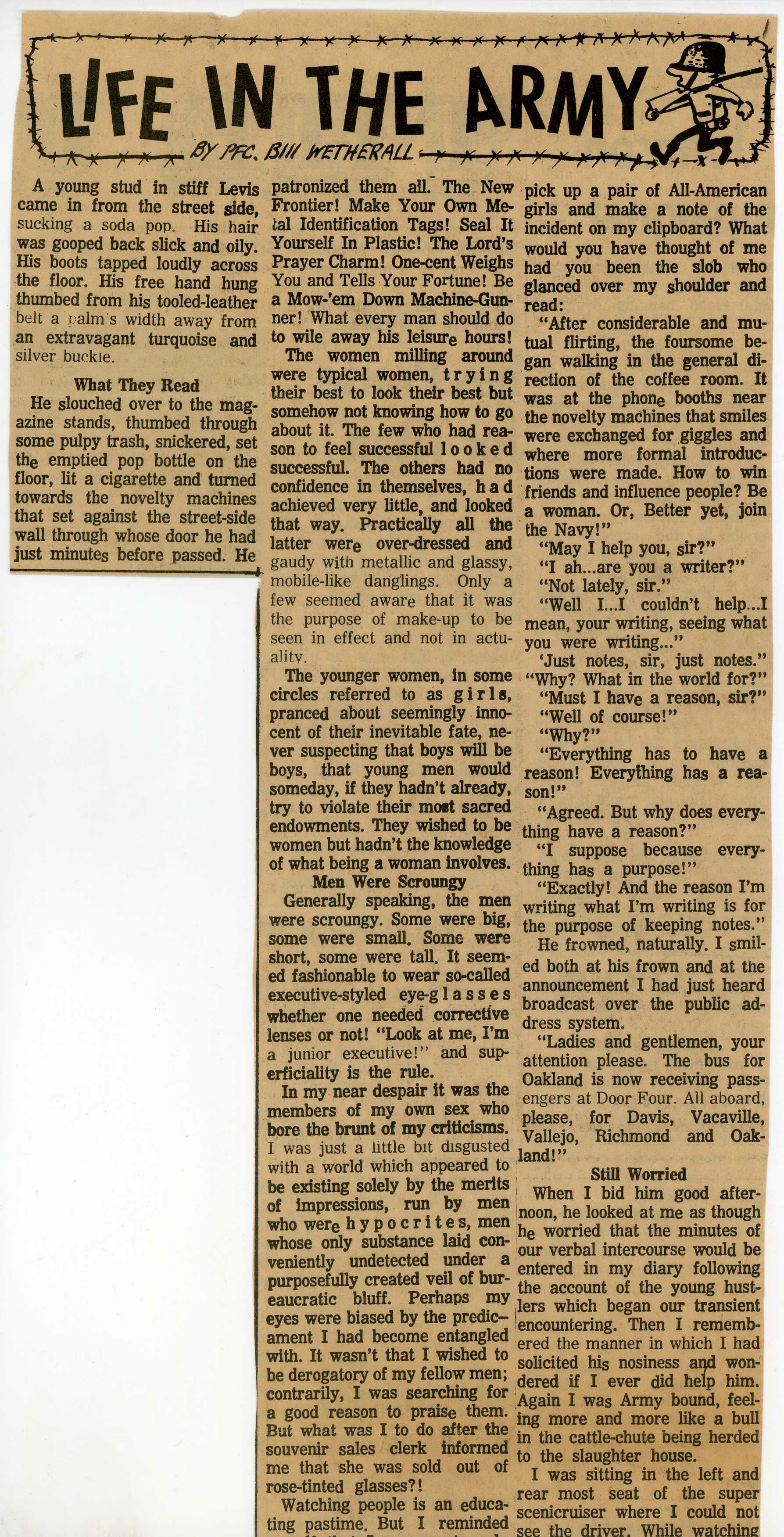

Life in the Army 1By Pfc. Bill WetherallThe Union Chapter 1: A Long Day's JourneyA young stud in stiff Levis came in from the street side, sucking a soda pop. His hair was gooped back slick and oily. His boots tapped loudly across the floor. His free hand hung thumbed from his tooled-leather belt a palm's width away from an extravagant turquoise and silver buckle. What They ReadHe slouched over to the magazine stands, thumbed through some pulpy trash, snickered, set the emptied pop bottle on the floor, lit a cigarette and turned towards the novelty machines that set [sic = sat] against the street-side wall through whose door he had just minutes before passed. He patronized them all. The New Frontier! Make Your Own Metal Identification Tags! Seal It Yourself In Plastic! The Lord's Prayer Charm! One-cent Weighs You and Tells Your Fortune! Be a Mow-'em Down Machine-Gunner! What every man should do to wile away his leisure hours! The women milling around were typical women, trying their best to look their best but somehow not knowing how to go about it. The few who had reason to feel successful looked successful. The others had no confidence in themselves, had achieved very little, and looked that way. Practically all the latter were over-dressed and gaudy with metallic and glassy, mobile-like danglings. Only a few seemed aware that it was the purpose of make-up to be seen in effect and not in actuality. The younger women, in some circles referred to as girls, pranced about seemingly innocent of their inevitable fate, never suspecting that boys will be boys, that young men would someday, if they hadn't already, try to violate their most sacred endowments. They wished to be women but hadn't the knowledge of what being a woman involves. Men Were ScroungyGenerally speaking, the men were scroungy. Some were big, some were small. Some were short, some were tall. It seemed fashionable to wear so-called executive-styled eye-glasses whether one needed corrective lenses or not! "Look at me, I'm a junior executive!" and superficiality is the rule. In my near despair it was the members of my own sex who bore the brunt of my criticisms. I was just a little bit disgusted with a world which appeared to be existing solely by the merits of impressions, run by men who were hypocrites, men whose only substance laid conveniently undetected under a purposefully created veil of bureaucratic bluff. Perhaps my eyes were biased by the predicament I had become entangled with. It wasn't that I wished to be derogatory of my fellow men; contrarily, I was searching for a good reason to praise them. But what was I to do after the souvenir sales clerk informed me that she was sold out of rose-tinted glasses?! Watching people is an educating pastime. But I reminded myself that I was most probably not alone in my engrossments, that somewhere in the depot were other persons staching me, wondering about me just as I was wondering about them, and making similar and equally numerous errors of judgment! How many minds had pigeonm-holed me for just another teeage punk outfitted in collegiate attire was a matter open for speculation. What It ReadWhat would you have thought of me if you had watched me watch a couple of boat-jockeys pick up a pair of All-American girls and make a note of the incident on my clipboard? What would you have thought of me had you been the slob who glanced over my shoulder and read: "After considerable and mutual flirting, the foursome began walking in the general direction of the coffee room. It was at the phone booths near the novelty machines that smiles were exchanged for giggles and where more formal introductions were made. How to win friends and influence people? Be a woman. Or, Better yet, join the Navy! "May I help you, sir? "I ah . . . are you a writer?" "Not lately, sir." "Well I . . . I couldn't help . . . l mean, your writing, seeing what you were writing . . ." "Just notes, sir, just notes." "Why? What in the world for?" "Must I have a reason, sir?". "Well of course!" "Why?" "Everything has to have a reason! Everything has a reason!" "Agreed. But why does everything have a reason?" "I suppose because everything has a purpose!" "Exactly! And the reason I'm writing what I'm writing is for the purpose of keeping notes." He frowned, naturally. I smiled both at his frown and at the announcement I had just heard broadcast over the public address system. "Ladies and gentlemen, your attention please. The bus for Oakland is now receiving passengers at Door Four. All aboard, please, for Davis, Vacaville, Vallejo, Richmond and Oakland!" Still WorriedWhen I bid him good afternoon, he looked at me as though he worried that the minutes of our verbal intercourse would be entered in my diary following the account of the young hustlers which began our transient encountering. Then I remembered the manner in which I had solicited his nosiness and wondered if I ever did help him. Again I was Army bound, feeling more and more like a bull in the cattle-chute being herded to the slaughter house. I was sitting in the left and rear most seat of the super semicruiser where I could not see the driver. While watching the valley rush by, I forgot all about my destination, and in fact, about even the type of bus in which I was riding. My adventurous preoccupations were suddently pierced by the soundings of a horn from somewhere beside us. Still day-dreaming, I looked towards where our driver should have been, only to see what took a few confused seconds to resolve itself as the upper deck windshield. On that moment's stupored misperception I fell asleep, an alien to my ideosyncrasies. It was the application of brakes and the deep and scratchy voice that claimed us to be pulling into the Oakland terminal that woke me; while assembling my faculties and gathering my effects, I recollected what I had been dreaming . . . something about loosing a filling! Few Lights AwayI can still feel my tongue searching for to fondle the comminuted fragments that I imagined to be grinding in my bite as I stepped off the bus that foggy afternoon, knowing only one thing for sure, that I was but a few stop lights away from being a soldier! While hurrying through the glass doors that doubled for loading gates, I was looking for something, for anything, that might take my mind off what had to come. And then, right there in front of me, I saw what I needed. An elderly but solid and healthy woman was leading her hunch-backed and hard of hearing husband through the crowd, by the arm, though to my humor wanting eyes, by the ear! "Come along now, Elmer. Our bus is here." "Eh? Eh?" I could see it all years from then, when perhaps it would be Martha saying to me in her gentle way, "Come along now, Billy." "Eh? Eh?" I conceded that it wouldn't be too bad a life if we loved each other; perhaps all I would have to do to keep her happy and to demonstrate to her how appreciative I was of her benevolent guidance is to nibble on her ear every other night or so while my dentures smiled at her's [sic = hers] from their glasses on the bed stand! Red Carpet RolledThe recruiting station put me up at the St. Mark's for that night and provided for my dinner and subsequent breakfast with two meal tickets to Mel's Drive-In. The red carpet had been rolled out, not deep pile, but, nevertheless, red! I was to process after breakfast the next morning and leave for Fort Ord the following afternoon. Having established myself six floors above Oakland, I decided to seek philosophical reassurance and otherwise be cheered up by my friends and fellow students at the Big U. Berkeley never looked so good as it looked that evening; it was difficult to face the time I had to leave the sincere and congenial hospitality of those few young men I prided myself as having for my friends! I don't remember the exact moment I fell asleep but that it seemed a mighty long time after I first felt the clean linen and began the restless pondering that kept me awake. (To Be Continued) |

Life in the Army 2

By Pfc. Bill Wetherall

The Union

Friday, 30 Oct 1964

Chapter 2: The Recruiting Station

It was just about the time had discovered an antiquated ore car nearly buried in the silt of a remote ravine that a phone began ringing. I couldn't quite comprehend a phone being in an area that was so far removed from even a jeep trail that I had had to hoof it an incredible distance to get there; nevertheless, there was the phone, behind the tail-gate, its receiver leaping out of its cradle towards my free hand, and, there I was, sitting on the edge of an unfamiliar bed, holding a Princess against my ear and hearing a stranger's machine-like voice infer a most disenspiriting message!

"Good morning, sir. It's 6:00 o'clock."

"Good morning, sir, and thank you kindly!" I replied, remembering where I was and my purpose for being there.

I really don't believe that the registrar was accustomed to such radiant response to his Department of Army subsidized reveille calls; however, his greeting was the last pleasant morning salute I had an occasion to return for a good many weeks.

Mel's wasn't the most enchanting place to be tray-served burnt eggs, either, but, because I was hungry, I was able to choke them down and be on my way to the recruiter's.

Plenty of Company

I was not to be alone with my intellectural [sic = intellectual] excruciations; approximately 30 others were already there, waiting as I would be waiting to be processed, and I was told that more were to come. When there were enough of us to justify that the operation be commenced, a roll-call was taken to account for those present and we were briefed as to what we could expect to be doing for the next four hours or so.

To begin with, about 50 of us were taken to a testing room where a mousy-mouthed lifer with a monotonous voice of authority talked us through the filling out of various information forms, including medical history and record forms.

"In Box 'A' print your last name first, first name and middle initial only! If you have no middle initial write NMI and surround with parenthesis [sic = parentheses]. Yes? What is it?!"

"What are . . . is a . . . surround with pharempt . . . ah . . . those things?" asked a freckle-faced kid from the third row.

"Parenthesis [sic = Parentheses]? Like this. . . ." explained the administrator with chalk and blackboard.

Satisfied that he had success fully demonstrated what parenthesis [sic = parentheses] were, but sensing an awkwardness about the boy's grasping nod, the administrator asked for the prospective soldier's name as though anticipating a "need to know'.

"What's your name, son?!"

"Daniel Johnson."

It came weak and prideless, a manner which obviously irritated the administrator who, pretending not to be moved, tried to repress his perplexions by nonchalantly taking up from where he had been forced to leave off.

State Your Race

"In Box 'B' state your race. Now listen closely. All of you can be classified to fall in one of the following racial groups: white or Caucasian; black or Negroid; brown or Malayan, yellow or Oriental or Mongoloid. Also, if an American Indian, consider yourself as yet another classification. Are there any questions? Yes?"

"Is this what you mean?" asked the red-headed owner of an extended paw while rising from his chair.

All that followed the administrator's attentive footsteps was whispered ejaculation which sounded nothing like 'That's the idea, Johnson.'

"Now what did I say!" (soft) "Did I even suggest sex?" (a little bit louder) "I said race!" (very much louder) "We're in Box 'B'." (the intensity of his voice was diminshing [sic = diminishing] from that of his preceding utterance) "Your race is Caucasian, not male; now please, young man, sit down, place a check before caucasian [sic = Caucasian] in Box 'B' and in the future try paying attention to what I'm putting out. . ." (silence was his most virtuous tact)

"Anyone else having trouble beside friend here?" he continued, waving his hand towards Johnson. "Please stop me if I'm going too fast. All right now. In Box 'C' indicate your sex. One fellow has already accomplished this so you, Johnson, put your pencil down!

"Now if you're wearing britches and have short hair and don't lie you're definitely not a WAC. NO one in this room I should have circled female!

"Box 'F' pertains to your marital status. You're allowed to be single, married or divorced.

"In Box 'G' . . . Box 'G' is directly beneath Box 'F' . . . in Box 'G' I want you men who are married to print your current wife's Maiden name. Question! Johnson!"

Johnson Again

Each of us contorted ourself what ever way was necessary to permit ourself an unobstructed view of the red hair and freckles that became nearly in distinguishable from the coloring that took to the lad's face when he stood up and asked, "What if you're not married. . . ?"

After finishing with the forms, we were administered what amounted to an Armed Forces Intelligence Test. We were told that the test would reveal the potentials of our native intelligences.

Next we were administered a series of aptitude tests covering the general vocational categories of mechanical, automotive, electrical and clerical. It was explained to us that the tests would disclose for which of these general vocational categories our combined assets of intelligence, cabability [sic = capability] and interest were best suited.

The various questions included sets of pictures among from which we were to choose, as for example in one such question from the electrical aptitude test, the picture which bore some relationship to a household fuse. If from among the pictures designated A, B, C and D respectively of a screw-driver, a carburetor, a household fuse clip and a typewriter eraser you chose the letter which corresponded to the household fuse clip, you were showing a "high" appitude [sic = aptitude] for electronics.

If you held a PhD in electrical engineering and had had years of civilian experience in microwave techniques but had never during your leisure hours taken the time to check-out the cellar fuse-box, well, there you were, just out of luck! On the other hand, if you had never in your life owned a car and had never become involved in automobile mechanics but had somewhere during your travels and seen a bill-board advertising a super-duper oil filter, and if in a similar analog question in the automotive aptitude test you had correctly chosen the picture of a can of SAE 30 motor oil as being related to an oil filter, well, there you were, made out to be ideally suited for a grease gun, a young fellow who just didn't know that his sub-conscious "and of course most important" motivations wanted him to be a mechanics helper in the United States Army.

Scores Give Clues

That you had the hands and self-discipline of a surgeon did not matter a job [sic = jot] beside your army aptitude profile scores which made you out to have the "potential" of being a damn good ambulance driver!

Having finished with the testing, those of us who had not already been given physical examinations were directed to the dispensary. The medical was hurried but thorough. It was not as simple as the one which is rumored to have been administered during the war years.

It is said that war-time draftees were lined up against a wall and individually paged over to an opposite corner for counseling. If they responded, they were considered in good shape. After all, they had heard their names being called, they had seen where to go and they had gone there. What farther information was relevant?

The last station before lunch was the security station. There we were asked to read the lengthy and fine-printed "Attorney General's List of Subversive Organizations", after which we were to answer various yes or no questions concerning both or either the degree of our affiliation with such organizations and or the extent of our relations with persons we knew to have had affiliations with such organizations.

(To Be Continued)

Life in the Army 3

By Pfc. Bill Wetherall

The Union

Monday, 2 November 1964

About a minute bad passed since we had been instructed to read the Attorney General's List and the related security risk information when the monitor asked, "Anyone not finished the reading?" I was the only one who raised my hand. "I'll give you a couple more minutes." His manner was short but polite.

Meanwhile, the other processees were as fidgety as a gang of athiests [sic = atheists] in church. By my being particularly careful to read every last word and by they being careless, they had only to sit and twiddle their thumbs, for the monitor would not allow them to answer such questions as "are you now or have you ever been a member of the communist party" until everyone had finished the reading.

"Are you finished reading back there?" I detected a trace of impatience in his military posture.

"No sir, not yet."

"Hmph!" You're kinda slow. Let's hurry it up; everyone else has been able to finish. . ."

"All right, sir, I'm done now."

Wanting to finish what he had started to say to me but wanting more to get on to lunch, the monitor proceded [sic = proceeded] to instruct us in the manner in which we were to complete the remainder of the questionnaire.

Only Answer Yes

"You will notice that the first question, I have read the foregoing statements and understand their implications, is already answered for you. The only possible answer to this question is yes, for if you hadn't read it and understood what you have just read, your answers to the questions you will answer wouldn't be valid and, therefore, couldn't be considered binding!" His tone reflected the rudiments that would make his statement an order. We would complete the questionnaire, wouldn't we!?

It is interesting to note that every last question was stated in the past tense, that is, the questions referred to your thoughts and actions as they occurred in the past. In no way could your answering the questions commit you to certain thoughts and actions that might come to involve you in the future. In other words, the security risk questionnaire was not a resolution of what you would or would not think and do, rather, it was an affidavit of what you had thought and done.

Such is how the sequence of events was transpiring as of about noon, 17 October 1964. I was just another processee being processed, an anonymous figure to say the least.

"Follow the red line to Station 'B'." "Follow the brown line to Station 'F'." And talk about lines. If I wasn't standing in one I was being led [to] one. Never in my life had I had to shovel my way through so much except be it the day I went to work for Smokey the Bear.

I was provided with a lunch ticket good only at Mel's and informed that I had three hours to kill before I was to undergo the final stages of my being recruited, namely, the determining of my choice, not chance training and the taking of the oath.

Accent Seasoning

The grease burgers were terrible. Horsemeat, I believed them to be, seasoned with accent [sic = Accent], but of course! I gave them up for dog food, a value judgment arrived at through the mutual consent of my stomach which told me how basically tolerant it was and my emotions which led me to believe myself a dog. I ate as fast as I could so as to get started for the not too far distant used-book store I had glimpsed during my wanderings of the day before.

The book store was a true culural [sic = cultural] enclave against the surrounding mulitude [sic = multitude] of pawn shops whose every uttered vestibule framed its lousy proprietor who typically had nothing more than a belly, a cigar and a profane grunt to offer every Dick and Jane who happened to pass his place and have the audacity to ignore his sidewalk soliciting. . .

"Hey, Guy! You a soldier? I've got just the thing for you. Come on in."

"Sorry, sir, but you're wrong."

"What?"

"I'm not a soldier and you've not a damn thing that could possibly interest me!"

Just for the fun of it, for I wouldn't dream of parting with them, I offered another clown who insisted that he had something I needed -- ninety pounds of square nails at 40 cents a pound! I gathered as much from his ensuing sneer that he didn't especially appreciate my philanthropic intentions to supplement his junk collection with the rusty authenticity so characteristic of my Gold Rush artifacts; in retrospect, I'm most grateful that he wasn't a genuine antiquarian, for if he was, and if he had desired to take advantage of my proposal to him, he certaintly [sic = certainly] had his bodyguard "business associates" as the only witnesses he needed to enable him to insist upon and legally enforce a transaction!

My mood was of a cantankerous nature modulated by a degree of sarcasm; 1 was embittered by the impositions I felt myself unjustly burdened with. Oh yes I was wrong and God only knows how many men and women thought that they saw in my face the very soul of the Devil's animosity! But who was I to know then that I was wrong; then, when even children's smiles were snarls and every laugh a shout?!

Thank God for used book stores whose fuggy yet wholesome atmospheres are somehow capable of enlightening and fascinating a mind so distressed as was mine; I had before sought refuge amongst teetering racks of musty volumes and thus knew well the nature of a dusty book's spiritual soothings.

Forgets Dilemma

It wasn't long before I had I had forgotten the dilemma that I had imagined myself a victim of; neither did it seem long before my Guardian Angel told me that my time was up by reminding me of my "sense of duty".!

Even though I was $3.50 lighter, I never once hosted the thought that I had lost in the bargaining; I was delighted that I had found such readable publications as I did find. "The Life of Pat Garrett! An Introduction to Human Anatomy! A Plea for Monogamy!" I was actually thawed out by the time I had climbed the stairs which led to the recruiter's office and sat myself down in the lounge to await my turn to be given my choice not chance "counselling".

These books were John Milton Scanland, The Life of Pat Garrett, Colorado Springs: J.J. Lipsey, 1952 (reprint of 1908 pamphlet); Clyde Marshall, An Introduction to Human Anatomy, Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders (went through several editions down to the time I was in the Army); and Wilfrid Lay, A Plea for Monogamy, New York: Boni and Liveright Publishers, 1923 (had many printings). I no longer have any of these titles. I replaced the anatomy book with a Japanese printing of the then current English edition of Gray's Anatomy, also published by Saunders, in 1966, when serving as a lab tech in the 106th General Hospital in Japan. In the fall of 1969, after completely my BA at Berkeley, just before going to Japan, I sold several boxes of books to a used book dealer in Berkeley. I did not begin the collection that would become Yosha Bunko until returning to graduate school at Berkeley in 1972. All of the books I acquired during my 3 years of grad-school residency were shipped to Japan when I permanently returned in 1975.

(To Be Continued)

Life in the Army 4

By Pfc. Bill Wetherall

The Union

Friday, 6 November 1964

The choice not chance bit was quick. Painless. Reckless. Foolish. And after we had all been thoroughly snowed, the 18 of us who were to leave for Fort Ord that evening were rushed to the rooms wherein we were to take the oath.

We had all taken the oath, eaten our last civilian mean and walked the five blocks to the bus depot when I first noticed that I was tired. It was only 5:30 and we had to wait 40 minutes for a bus to San Jose, which, when it did come, proved to be one of those evening commuters that stops at every housing project that has a shopping center as its nucleus and sports a fancy name conceived by some second rate architect to suggest paradise but usually provoking [sic = provoked] me to picture in my mind only the helpless suckers who think that No Money Down and 30 Years to Pay is the only way to fly . . . The fellows were pumping their last dimes into the game machines and taking pictures of themselves and pacing the depot as though life was a bore and pointless self-entertainment a manifestation of their "I'll show them how tough I am" neurosis.

Calm in Mood

When at last on the road, I became surprisingly calm, confident that there was not a thing on the earthly side of Hell that could break the will that took so many years of unknown determination to establish itself in the cavity that was my thick skull!

I don t remember much about our changing buses in San Jose; long before then I had become numb to anything that wasn't directly related to sleep. Not even the frequent and jerky roadside stops bothered me. I knew we would be late getting into Fort Ord and even later getting settled in our billets. And that omnipresent innate birdie had told me that we would be up and around very, very early the next morning!

It was a crescendo of mumbling that stirred me from my sleep and inspired me to look out my window in the void that was the darkness on its other side were the glaring lights of what settled down to become an MP Guard Post. Off to our flank and illmuinated by its own brightness stood a sign that told its own story. Welcome to Fort Ord!

After being hustled off the bus, we were packed into a room that seemed already filled with desks and ordered to be seated. For nearly two hours the sergeant in charge proceded [sic = proceeded] to spoon feed us through the filling out of two IBM cards which amounted to address cards.

We were then pseudo-marched over to a building which we were told was the reception company orderly room and for the next half hour Welcomed to Fort Ord and Assured that we would find our weeks of training there both profitable and interesting! Afterwards, we were filed past the supply building from which were thrown at us two blankets, two sheets, a pillow and case and believe it or not, a Military Gift Pac, a very big deal about like what you'd expect to find only at the very bottom of the most shelf-staled box of cracker jacks [sic = Cracker Jack]; a cardboard box, it was, filled with the following goodies from grandma's kitchen: safety razor, razor blades, shampoo, after-shave lotion, foot-powder, underarm deordant, mung! [sic = and an underarm deodorant called Mum!] Guaranteed to keep your arms glued to your sides for 24 hours! With mung [sic = Mum!] the odor can't get out!

For all I knew or cared, the Gift Pac could have been a package from care [sic = Care, CARE] or a morale booster from the Salvation Army. Actually, it was tax money in disguise.

Remember Poster

Our arms will-loaded [sic = were loaded] with both our personal effects and the items that we had just been essued [sic = issues], we were double-timed to what was to be our barracks for the few days it would take us to be outfitted with clothing and "mentally conditioned" for what was to come and generally introduced to the fellow who had said, while his crippled finger pointed to us from his Post Office posters, "Uncle Sam needs You!"

We were shown how to make a military bed, a procedure no different than that of making a civilian bed as far as I could see except that army blankets were used, and the mattresses were thinner, and there were no box springs, and the pillows were scrawny little lumps of muslin-sacked feathers that were to the ones back home about like a hummingbird's rump is to an eagle's mustache! The sergeant managed to thoroughly confuse the majority who had never in their lives made a bed . . .

We were at last left to ourselves to get as much sleep as was possible; none of us knew just when to expect the lights to be turned on and our tired bodies harassed through pre-reveille chores. For the second night in a row my linen was clean, but that morning I knew the moment I fell asleep; it was just about the time a 60-watt bulb and a cadreman's war cry intruded on the privacies of my nocturnal meditations.

Chapter 3: Reception Company

"Where am I?! Where's my faded, pea-green quilt?! Who are those jokers with sleep in their eyes?! Who is that idiot in a soldier costume screaming for us to get out of those racks!"?!

"But yes! I am in the Army. I am in Barracks Twelve, upstairs and on the eastside, in the top bunk of the fifth double rack from the northside stairs.

"I am William Owen Weatherall [sic = Wetherall] alias RA19779952, alias Line Number 50 on Roster Number 205!" Standing, but still clinging to my rack for support, I yawned and I stretched and I dug the lacrimal deposits from the corners of my eyes.

The cadreman's yelling subsided as soon as everyone's feet had thumped on the deck thus signifying that all of us were at least up if not yet thoroughly awake. It was only 0430 and so black outside that one fellow couldn't decide if he was really getting up or just going to bed.

I learned immediately the significance of negative thinking. I had never before believed that so many fellows could be so completely serious when their replies to my "Good morning!" took on the firmness and acidity of sour grapes.

"Good morning, Dumbler!"

"What's good about it?!"

"Good morning, Carroll!"

"What are you, Wetherall, some kinda nut??!

"What's new and exciting, Dale?!"

"Get the hell out of here!"

(To Be Continued)

Life in the Army 5

By Pfc. Bill Wetherall

The Union

Monday, 9 November 1964

Never More Serious

I learned that while reflecting such dispositions, that these fellows were never more serious in their lives. And I realized what promoted one young San Franciscan to state that be thought conditions "better at the Fleishhacker [sic = Fleishaker] Zoo!" The morale was to say the least, at a dangerously low ebb.

It had been so late when we arrived the night before and we had all been so tired that it never occurred to any of the 18 of us that there were men asleep in the other barracks that were then unlit and so ghostly still. But that morning we could see at least 10 other barracks lit up, and we could see behind their windows what seemed like hundreds of young men caught up in the same insanity that had snared the 18 of us just the day before, hundreds of bald and white headed figures running around like so many chickens with their heads hacked off, most of them garbed in new, still sheeny, olive-green green uniforms but a few, like ourselves, still in their "civies," [sic = "civies",] all of them engaged in one activity or another, sweeping floors, emptying garbage cans, dusting window sills, laughing, horseplaying, momentarily serious like us, wondering, worrying, scared, expecting God only knew what!

We were allowed to ample time to wash our faces and shave from them the uncomfortable stubbles and make our bunks and GI the barracks and stand around and spread rumors and wait and wait and wonder what was going to happen next and when it was going to happen.

The sky in the east had grown lighter, until it glowed a softly streaked, orange blue-gray; it felt good to sit on the front porch and unleash my mind to wander through the memorious hallways wherein rested last summer's sunrises from American Hill cabin!

At last the order came to fall out. "Attention! All personnel in the reception company area! Fall out for Reveille and morning chow between barracks 13 and 14! On the double! Let's go! You men are moving e-n-t-i-r-e-l-y too slow! Attention! All personnel . . .!

Wire Voice-tubes

When the outdoor speakers that culminated the wire voice tubes that were a part of the recruit mustering system that was controlled from the orderly room had stopped their nearly undecipherable blarring [sic = blaring], all I could hear was the hard-pounding of boots and shoes on the dirt paths and paved streets superimposed on the noise that was the product of a most mad commotion that I was in the very middle of, churning my legs, not having the faintest idea where Barracks 13 and 14 were, just keeping up with the herd and hoping it knew where it was going.

Everywhere we went we double-timed. From the barracks to chow and from chow back to the barracks and from the barracks again to where ever it was we were to go we double-timed Those that persisted to move out as though they had lead in their pants were violently reprimanded by the cadre sergeants whose appearance alone was enough to scare any man who wasn't accustomed to mirror-black helmets underscored scored by hard-set eyes peering suspiciously from leather-tough faces necked to rigidly starched uniforms that seemed to move automatically towards you if you so much as thought of slowing down to think!

"What do you think you're doing, young trooper?? Come here!! Get your hands out of your pockets! You smell like a civilian! You make me sick! Stand straight when you stand before me! What are you chewing?"

"Gum . . ."

"Swallow it!"

"I'll take it . . ."

"I said to swallow it!"

". . . uglnk . . ."

Wipe Off Smile

"You may think you're still on the block but you aint . . . t-r-o-o-p-e-r you had better wipe that smirk off your mouth . . . you're in the Army now . . . and in the Army you'll act like a soldier! And soldiers move out when they're told to move out. Do you understand me?? D-o y-o-u u-n-d-e-r-s-t-a-n-d me?"

"Yeh . . ."

"Aint your mamma ever lernt you no manners? Yes Sergeant!"

"Yes, Sergeant . . ."

"Again!?"

"Yes Sergeant!"

"Move out!"

I didn't know whether the by would cry or go blind. He moved out as though death itself was on his trail, running all the way to the rear of the mass-formation of over 600 young men most of whom were equally as afraid as was he.

"You in the red sweater!" 'I'm wearing a red jacket . . .'

"You! Smiling!" 'I'm not smiling . . .'

"Come here!" 'What do you want with me? I'm from Grass Valley . . .'

When I turned towards the commanding voice. I saw the fellow who did fit the description already standing at attention before the sergeant and still smiling.

"What's your name, soldier?"

"Rosenburg, Sir."

"What??"

"Rosenburg, Sir!"

"Don't call me Sir; I work for a living!"

"Yeh . . . Yes Sir . . . ah Sergeant!"

"Rosenburg, you do not move. Rosenburg, you're an iceberg. Rosenburg, icebergs don't smile. Rosenburg, wipe that smile off your face. With your left hand, Rosenburg, wipe that smile off your face! With your other left, Rosenburg. Now throw it on the ground, Rosenburg. Now stomp on it, Rosenburg. Now pick it up and bring it to me, Rosenburg Thank you, Rosenburg. I said thank you, Rosenburg!"

"You're welcome, Sir . . . ah, Sergeant!"

"Get back in line and don't let me ever see you smile again, R-o-s-e-n-b-u-r-g-e-r!"

Chow Not Bad

The chow wasn't bad at all. Two eggs. Bacon. Hash browns. Hot or cold cereal. Juice. Toast. Butter. Jam. Coffee, or white or chocolate milk.

When finished with breakfast, we were allowed to brush our teeth and square away the bays and latrines. Afterwards, we were again fallen out, this time by Roster Number, for what proved to be a police call formation.

There hasn't been a morning since that I haven't had the discontented pleasure of walking around for ten minutes stooped over, picking up cigarette paper, cigarette butts, match sticks, used and discarded tissue paper, candy wrappers, pop-bottles, beer cans and the residue from that new craze that's sweeping the nation, the thumb-tabs from those quick-open and aluminum-topped beer cans.

That morning I counted laying heaped in my grubby hands 12 cigarette butts, 27 cardboard match sticks, 3 wooden match sticks, one ice cream stick, half a pretzel, the greater part of a broken button, and a thumbtack which I put into my pocket along with a good rubber band. Imagine, if you will, how I feel when I see the majority of those who smoke who are the majority of all soldiers rid themselves of their nearly vaporized but still steaming cancer-sticks by the simple flicking of their social finger in the most convenient direction totally disregardant of the "very difficult Confucian concept" that if they would throw nothing on the ground that [sic = then] there would be nothing on the ground that would require being picked up and therefore no need for police call . . .

(To Be Continued)

Life in the Army 6

By Pfc. Bill Wetherall

The Union

Tuesday, 10 November 1964

As it was, it seemed as though we would have a daily police call if for no other reason than to be "kept busy doing something in case an inspector should 'chance' by." The way it was was this. If it moved salute it. If it didn't move pick it up. If you couldn't pick it up plant it.

Get Fatigue Clothing

After police call we were marched over to a group of buildings that were collectively called the ARMY QUARTERMASTER'S store and I knew that I was wearing my civilian clothes for the last minutes for many weeks. At one Quartermaster's building we were issued our fatigue clothing.

Now fatigues, as issued, are not exactly custom tailored. But you do have a sizeable choice. Small, medium or large. You can take your pick between their being either too small or too large. Seldom will they ever be "just right!" I prefer my fatigues on the large Side if I can't have them fit correctly.

"Everyone who is of medium build up here!" Good-bye "civies"!

Dressed in fatigues and a soft cap but still with our civilian footwear, we were marched, each of us with his half-full duffle [sic = duffel] bag thrown over his shoulder, to a second Quartermaster's building where we were issued our dress uniforms and shoes and our boots and underwear. These items are issued by the same spectrum of measured sizes as ready-made slacks, sport jackets and dress shirts are available in in civilian life. It should be pointed out for purposes of clarity, however, that the Army Quartermaster's Store isn't exactly a Bennett's Bootery and Haberdashery!

"What can I do you for, Bill?"

"Howdy, Frank! I'd like to see something new in fatigues!"

"You've come to the right place, Willy; why don^ you take five or six pairs in assorted colors?"

"Well, really, a nice olive drab will do . . ."

And so is the way things progressed for the next five days at Reception Company. We were given shots, all by the pneumatic gun technique. We were subjected to further apptitude [sic = aptitude] testing. We were escorted to football games. We were marched to movies. Attendance was, of course, mandatory.

None Flattering

We were given dog tags and identification cards. The pictures on the ID Cards resembled mug shots, to be sure; I didn't see a one that could be considered flattering!

Their faces had lost their character when the greasy hair that had once hung down over their eyebrows had been pulled back over their foreheads and cut off. But let me tell you about those haircuts.

Every recruit on Roster 205 with the exception of myself was scalped raspy-smooth all but for a little mop on top about three-eighths of an inch tall. I was scolded for having my hair too short. (Good work, Mairon!) But what else could they have expected, what, I coming from an area where summertime swimming at Bridgeport wants my hair to be short? However, since I didn't even have the three-eighths of an inch mop on top, I was different, not uniform with the others, and, thought the Army, showing much too much individualism therefore! In other words, my haircut was not according to reception company SOP (Standard Operating Proceedure [sic = Procedure]). But what is perhaps the most appalling of all reception company SOPs is the requirement that new recruits pay 75 cents for their very first and most painful military haircut!

To watch the expressions on a recruit's face as he loses his locks is indeed a most phenomenally unforgetable [sic = unforgettable] experience. You would think the new recruit's civilian hair his dearest possession, his hairdo in fact the most magnitudinal self-erected edifice self-dedicated to his personality . . .

Said one barber to the first pimply complexioned hot-rodder that was to have his hair cut, "How do you want it cut?"

Taking the barber seriously, believing that Roster 205 was an experimental control group organic to the Commanding General's doctoral theses [sic = thesis] "psychological identity as a function of self-organized fibrous scepular [sic = scalpular] appendages," the boy answered, "Leave the sideburns, just trim up the edges and lay off the top!"

Loses Individuality

No words in my vocabulary are capable of properly portraying the expression that crossed and hung on the boys face when the barber's heavy-duty shears mowed a saggital grove a full two inches wide and at least that deep straight down the middle of the dandruff clogged excrescence that was the boys very last individual expression of his contempt for society!

Sewn over the left pocket of all fatigue shirts and jackets is a strip of black cloth embroidered in yellow thread U.S. Army. Over the right pocket is your name tag, a white cloth with your name embroidered or printed in black thread or ink. The idea is that, while standing before a mirror, you are supposed to associate your name with the other name that is "nearest your heart"! Everywhere we went, everything we did, reminded us of the predicament of our being in the Army. No one would let us forget that fact.

We drew field gear. Shelter halves (pup tents). Steel pots (helmets). Entrenching tools (shovels). Canteens. Pistol belts. Mess kits. Back Packs and suspenders.

We were introduced to the chaplain who encouraged us all to seek "spiritual guidance" during those troubled days when we felt like going AWOL (Away With Out Leave).

We were put to mowing, trimming, raking and watering the lawns that surrounded the barracks. We learned the funda- methods [sic = fundamentals, fundamental methods] of sweeping, mopping, waxing and buffing tile floors. And painting. And folding blankets. And preparing soiled linen for the laundry. And there came to be understood the Army's paraphrase of Candid Camera's famous pseudo-aphorism: Smile! You're on KP!

While strolling through the company area on Sunday afternoon I turned a sharp corner only to run into a fast walking uniform that bore the momentous weight of badges and patches ostentatiously sufficient to make the man inside it feel right at home if he were to stand beside a Tahoe National Forest office boy! Since the old soldier wore Master Sergeant stripes with a star in the middle, I figured him for an officer, and I snapped him a rather crude, uncoordinated salute. He was nice about it.

"That's all right, soldier. You don't have to salute me. I'm a non-com. Salute only those whose uniforms have black strips of cloth around the wrists of the sleeves and down the trouser seams."

"Thank you for the information, Sir. Would you please tell me what the star indicates?"

"No need to call me sir, either. The star simply means I'm a Sergeant Major. And so you're to address me simply as sergeant. It won't take you long to learn to recognize the various ranks."

Pleasant Change

It was a pleasant change of atmosphere to be talked to and not screamed at.

For recruits, reception company is a wayside stop between civilian life and military life. It provides recruits with the essentials preparatory to their military life, namely, their clothing and their orientation.

The processing procedure at reception company is to hurry up and wait, to hurry up to stand in line for period [sic = periods] of time that frequently approach two two [sic = two] hours.

(To Be Continued)

Life in the Army 7

By Pfc. Bill Wetherall

The Union

Wednesday, 11 November 1964

It was during those six days at Reception Company that I learned the advantages of being blessed with a surname that is so far removed from the front of the alphabet as is W-e-t-h-e-r-a-l-l.

Having had all my life to stand at the end of most lines has contributed a great deal to the building of my more or less patient character; in fact, even when having the opportunity to compete by running for a position at the front of a line, I've more often that not found myself walking and assuming my normal alphabetical position. I've always found it definitly [sic = definitely] interesting and infinitely educational to watch the others become a mob. Not to mention the fact that those who first complete a particular phase of processing usually pull silly little time-biding details while waiting for the tail of the line to complete the phase.

Shuffles Free

During those six days at reception company I witnessed mobs whenever we were ordered to fall out of the barracks. And occasionally a group I was near would so suddenly and without the smallest warning become rowdy that time didn't permit my escaping them; thus finding myself in the middle of their demonstrations I would simply relax, and very soon I would be shuffled free of their expulsive shouting and shoving.

Harassment was constant. Evidently, however, we were more in this department than were our fathers. We were told that they had had to put up with many times the harassment that we would have to tolerate.

The barracks at reception company are dismally miserable dwellings. And it is always the common opinion amongst new recruits that everything at reception company is mild compared to what conditions would be like "up on the hill".

Because of its being mentioned by the sergeants, we knew the "hill" to be the place where basic training was actually to begin.

"You mongrels are gonna hafta shape up when you get "up on the hill"! [sic = get up on the hill!"]

As to where the "hill" was, all we knew was that it was "up that-a-way" somewhere . . .

Occasionally, a soldier who had been through a few weeks of basic would be walking through the reception company area on administrative business; whereupon seeing us he would bawl out, "You'll be sorry . . . you suckers!"

We were to find out later that day of Wednesday, 23 October 1964, that everything improves "up on the hill".

Chapter 4: Basic Infantry Training

We sat squashed in open-topped cattle trucks, each of us holding as best he could the heavy duffle [sic = duffel] bag that held his entire clothing issue, the laundry bag that held his field gear, and his personal particulars, the latter items being wedged between his arms and his rib cage; he daren't wave good bye to reception company lest he spill everything and have to suffer the harassment that would consequently hail down upon him.

We were not so sure we were glad to be leaving reception company; we were still of the opinion that the routine harassment had yet to begin.

We couldn't see just where we were going; we had only the dusk sky and motion to tell us that wherever it was we were going, lay a good walk south of the reception company area. We could feel the truck take the corners and pull the hills and brake to occasional stops only to buck forward and again be on its way. We felt like the blind man who wishes he could see all that he felt, smelled, tasted and heard.

Treated Quite Well

To our surprise we were treated reasonably well by the basic training cadre. We had to hustle, to be sure, but we had been led to believe that our landing "up on the Hill" would be so terrible that anything just short of being terrible was ecstasy.

Most of the barracks for basic trainees are new, three story, concrete and glass buildings, quite in keeping with the trend in apartment housing these days. Nothing so far as private rooms, you understand, but at least you have a bay that you and 50 others can call your very own.

I was fortunate enough to be on a roster that was assigned to the older but rejuvenated barracks. These barracks are wooden structures that were constructed during World War II as "temporary" buildings. The master plan calls for the gradual replacement of these older billets with the newer, concrete and glass architecture.

The older barracks, however, provide all the creature comforts and advantages of the newer dwellings, plus, I believe, the added convenience of having only one small building per platoon of 50 troops rather than a larger building for an entire company of 250 troops. Not only are their latrines tiled and plastic-paneled, but their bay walls and ceilings are sheet-rocked and their heating systems actually function after an adequate fashion. And the softness of their wooden members as contrasted with the aesthetic hardness of the newer barrack's [sic = barracks'] reinforced concrete beams greatly appeals to me.

Not Always Elite

There are ten men per basic training squad plus a squad leader, and four squads per platoon plus a platoon guide, a platoon sergeant and a platoon leader. The platoon leader is a non-commissioned officer (NCO), usually a sergeant, or a commissioned officer, normally a second lieutenant. The platoon sergeant and guide and the squad leaders are trainees chosen supposedly for their leadership abilities, et cetera. Needless to say, it is not uncommon to find that many of these "acting jacks" are in fact not the elite to be had from the young men available.

A company consists of five platoons plus the mess, supply and administrative personnel, a senior drill instructor (SDI) who is responsible for safely marching the trainees to and from classes and training areas and disciplining them in manners concerning dismounted drill, a first sergeant who is the NCO in charge (NCOIC), an executive officer (XO) and a commanding officer (CO), both of whom are in most cases a company grade officer, that is, second lieutenant, first lieutenant or captain.

At Fort Ord, the Company is the basic training unit. Reception company makes up as many as eight basic training companies per week, though the weekly quota is not normally so high.

(To Be Continued)

Life in the Army 8

By Pfc. Bill Wetherall

The Union

Thursday, 12 November 1964

Interesting Bore

Basic training itself was an extremely interesting bore. What I mean to say is that I would have been bored to tears had I not been extremely interested in human nature.

For two weeks we all but lived at the train fire ranges. A fellow got so tired of firing round after round of ammunition, day after day after day.

We had field classes in target detection wherein we were instructed in the first principles of distinguishing camouflaged enemy troops and war implements from the terrain, its foliage and its geological irregularities. We were taught the principles of first-aid and hygeine [sic = hygiene]. We were instructed in the procedures for handling intelligence information.

We were extensively briefed on matters involving the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ), or military law; we were told what we could do and what we could not do as a soldier. Correction. We were told what we would do and what we would not do as a soldier.

We were introduced to night-fire techniques. We were instructed in the art of pitching hand grenades; indeed, we threw live hand grenades.

We practiced night and day tactical marches; we were made aware of the combative problems that could be encountered during such marches. We were drilled in precision marching and facing movements with and without our rifles. We were trained in manual of arms movements.

Combat Techniques

We learned hand-to-hand combat techniques. We were exercised in bayonet maneuvers until they became second nature to us.

What is the spirit of the bayonet? we were asked.

"To kill!" we were ordered to scream in reply.

Two types of bayonet fighters?

"The quick and the dead!"

And which are you?

"The quick!"

We were told that there was no room for mercy in the heart of the bayonet fighter. I had to tell many a training sergeant who called me down for not screaming as I was ordered to scream that it was not the spirit of my heart to kill. Not understanding me, nor caring to, the sergeants would order me to drop to the ground and do a few pushups. If only they had known that vigorous exercise is to me no punishment at all . . .

We were taught the fundamentals of individual tactical movements, namely, how to crawl on our bellies and backs through tangled mazes of barbed wire while under machine-gun fire. How to crawl over logs and how to get into and out of trenches and over barriers while under machine-gun fire. In daytime and at night. That was called the infiltration course.

You Never Forget

And you could never forget lying on your back somewhere, you didn't know just where, out in the middle of the field, at night, listening to the machine-guns throw out burst after burst, listening to the projectiles crack over your head as the shock waves they pushed before their apexes slapped the moist air against your tympanic membranes, tracking the tracers that flew by, following their falling and watching them ricochet off the hill behind and arc gracefully high up into the black of night and describe a soft red trajectory, like does a planet amongst the stars; and that boot in your ribs from some other soldier who was trying to kick his way out of the barbed wire that he had caught himself up in, his mouth full of vulgar sand, you, forgetting the mysterious depths of the universe, rolling over on your stomach and digging your sore elbows and knees into the coarse and damp sand and pulling yourself forward, left elbow right knee, right elbow left knee, left elbow right knee, sliding down into the final trench, breathing, heavily, the machine-guns at last behind you, you, waiting, waiting, Alpha one charge, you crawling out of the trench, crouching, running, towards the bunker, down, prone, ready, kneeling, rocking, throwing a grenade, burying your face in your arm and your head in the sand, listening, expecting, knowing, looking, rising, running, charging, screaming, parring, thrusting, killing, withdrawing walking, sitting, resting, laying, sleeping . . .

God never made anything finer than a good soldier, had read a wooden arch that we had twice had to march under; while walking, while sitting, while resting, while laying, while sleeping, a few of us wondered. About many things.

The gas chamber was an experience to be had in civilian life only by those who are involved either as inciting participants or as innocent bystanders in a riot whose acme is quelled by tear gas.

Physical Routines

We became most proficient in various physical training routines consisting of pushups and body-twists and chinups and horizontal ladder movements and running the mile.

We took a 20 mile march that was nothing less and nothing more than hiking from Auburn to Grass Valley via the shoulder of Highway 49.

Bivouac was another big event during which we were given an opportune chance to practice what we had been taught concerning methods of field sanitation. Lasting for three days, the bivouac exercise stimulated more unprintable remarks than did any other phase of basic training.

It seems that not too many of the fellows were familiar with the ways of the woods. I was really impressed just how many of them had never before in their life camped-out. I sympathised with them only because I could never know just exactly what it feels like to feel so unsure of your environment that you are afraid of it. But I discovered that such fear was a common feeling among the recruits. They knew nothing about navigation, about remembering prominent landmarks, about ridges and drainages and creeks and the sun's path across the sky and that of the stars and moon at night and the nature of nature; when the sun did set and the stars and moon did come out, many of the troops feared even their own shadow.

We were thoroughly indoctrinated in the ethics and etiquettes of military courtesy. In summary, in eight long weeks, we were taught to march, to shoot and to salute.

It is required of all soldiers that they learn their chain of command, which consists of their squad leader up to and including the Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces, President Lyndon B. Johnson. It is further required of all soldiers that they learn both their eleven general orders and the six articles of their code of conduct.

The General Orders

- To take charge of this post and all government property in view.

- To walk my post in a military manner, keeping always on the alert and observing everything that takes place within sight or hearing.

- To report all violations of orders I am instructed to enforce.

- To repeat all calls from posts more distant from the guardhouse than my own.

- To quit my post only when properly relieved.

- To receive, obey and pass on to the sentinel who relieves me all orders from the commanding officer, officer of the day, and officers and non-commissioned officers of the guard only.

- To talk to no one except in the line of duty.

- To give the alarm in case of fire or disorder.

- To call the commander of the relief in any case not covered by instructions.

- To salute all officers and all colors and standards not cased.

- To be especially watchful at night and during the time for challenging, to challenge all persons on or near my post, and to allow no one to pass without proper authority.