Translations

Kobanashi and other humor

By William Wetherall

These are my translations of "kobanashi" or "little stories" of the comical kind, and other forms of humor, from senryū to one-line jokes.

|

Taiwan monkeys Small finger Blood clams Art museum Beauty shop |

Drug mecca American continent Bride hunting What is marriage? Divorce crisis |

Shortest kobanashi The river Sanzu Chinese match factory |

|

|

|

|

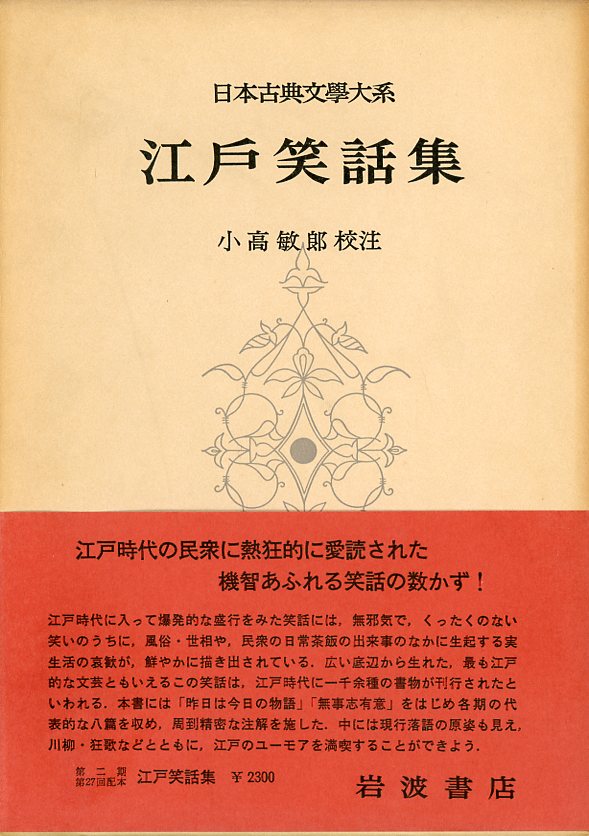

KobanashiKobanashi (小噺、小話) are short humorous stories, some just a line or two, others longer, which end in a punch line (ochi 落ち, sage 下げ) -- a word or phrase "dropped" in a manner that brings the story to a comical conclusion, often in the form of a pun. Such stories were told by "hanashika" (噺家、咄家、話家) or "danwaka" (談話家) -- "storytellers" or "raconteurs" -- before live audiences, in streets or theaters. Such story narrators were the forerunners of today's "rakugoka" (落語家), who generally perform while sitting on a zabuton on a stage, typically brandishing only a closed folding fan, which may be opened and used as a fan, or may be used to represent something in the story. Most of the stories told here are of fairly recent vintage, and some appear to be adaptations of jokes that originated in other languages. With rare exceptions as noted, all are unattributed and undated materials shared with me by friends. The translations and comments are mine. English translations of Japanese humorMy first encounters with Japanese humor were through the two collections shown to the right, by Norbert N. Kaneko (Kaneko Noboru 金子登 1907-1989), a humor researcher who, after World War II, worked for a while at the U.S. Embassy. Two jokes from the Old Japanese Humor volume especially amused me, and I have retold them many times. I relate them here, as Kaneko translated them, then show the originals and how they might have translated differently. Pot A hasty person wanted to buy a pot, but seeing the pot placed upside down, he grumbled, "Absurd! A pot without a mouth!" "Pot" is a translation of "Tsubo" (壺), which is one of the 44 stories in Tai no Misozu (鯛の味噌津), a collection most very short humorous anecdotes published in 1779 by Ōta Nanpo (大田南畝), a penname of Ōta Tan (大田覃Tan 1749-1823), who was also known as Shokusanjin (蜀山人). Ōta was a poet, painter, calligrapher, writer, and humorist. The collection is most conveniently anthologized in Odaka Toshio, collator and annotator, Edo waraibanashi shū, Nihon koten bungaku taikei (NKBT), Volume 100, Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten (小高敏郎、校注者、『江戸笑話集』、日本古典文學大系 100、東京:岩波書店), pages 423-448. The text of "Tsubo" and two related headnotes are found on page 435 of NKBT 100 (11th printing 1977, 1st printing 1966). The following transcription, romanization, and structural translation are mine. I have shown furigana in (parentheses) and transcribed all ditto script as 々. The romanization reflects the furigana. The translation reflects the headnote glosses of "sasaumono" and "berabou-na".

Kaneko's translation is suitably simple and unembellished. While I fully understood the humor, I found the "seeing the pot placed upside down" and "turned the pot back" a bit odd, because they seemed to imply that the man knew the pot was upside down. Whereas the point of the humor is that, in his haste, he didn't know. And it seems to me that the Japanese also implies that he was too careless. too inattentive, too aloof, even too dimwitted to realize that one of the pots had been stood on its open top with its closed bottom up. Bridge Toll A woman passed by the bridge-keeper's box, casting just one sen coin as the toll. The bridge-keeper called the women back, cenuringly, |

People who take it upon themselves to judge the woman's reasons for wanting to jump may think the reasons are "crazy" hence she herself is "crazy". But they cannot fault rationality -- her ability to "figure" that, if she's only going halfway, she should only pay half the fare. Choices of time, place, and method commonly reflect personality, which is always a component of one's state-of-mind.

I have used this story mainly to illustrate the way in which people who set out to take their own life can be rational to the very end. Impulsive suicides are also "planned" to the extent that the person who suddenly commits a self-destructive act has been contemplating dying as a solution to depression or rage and imagined how they might end their life with their own hand. They may seem to be "mad" during the final act of their life drama, but the act structurally (logically) follows the earlier acts of their life.

Urikotoba (賣言葉、売言葉) was a story book (hanashibon 噺本) illustrated by Isoda Koryūsai (礒田湖龍斎 1735-1790) signing as Koryū (湖龍画) and Doryūsai (土龍斎画). It was published in 1776 (An'ei 5 安永五年) by Seiseihan (整々畔), and prefaced and apparently written by Seiseihan Ichikazu [Shiwa] (整々畔市和序). The work is collected in Volume 10 of the 20-volume Hanashibon taikei, edited by Mutō Sadao and Oka Masahiko, and published by Tōkyōdō from 1975-1979 (武藤禎夫・岡雅彦編、『噺本大系』、東京:東京堂出版). I have not been able to examine it.

Taiwan monkeys

Translated by William Wetherall

台湾ザル

「台湾ザル5匹下さい」

「ありがとうございます。今すぐ用意できませんので、お待ち願います」

何日かして . . .

「用意出来ました」

「あれ、台湾ザル5匹といったのに一匹は日本ザルだぞ」

「お客様、それは通訳です」

Taiwan monkeys

"Give me 5 Taiwan monkeys."

"Thank you. I can't get them immediately, so please give me a little time."

A few days later . . .

"I got them."

"What? I said 5 Taiwan monkeys, but 1 is a Japanese monkey!"

"My dear customer, that's the translator."

Small finger

Translated by William Wetherall

小指

ヤクザが食堂にやってきました。テーブルに着くなり一番下のチンピラがすっと立ち上がり指を5本出し、

「おい、姉ちゃん、ビール5本」

「ハイ、お待ちどう様」

「おい、ちょっと待てよ、なんで大びん4本に小瓶なんだよ」

「あれ?一本小瓶じゃないんですか」

Small finger

Some yakuza come to an eatery. As soon as get to a table, the youngest punk quickly stands and holds up 5 fingers.

"Hey, waitress, 5 beers."

"Here you are. Sorry to keep you waiting."

"Hey, wait. Why 1 small bottle with 4 large ones?"

"Huh? Didn't you order 1 small bottle?"

This story hinges on the stereotype of a yakuza with a missing finger tip, hence a short finger that the waitress took to mean a small bottle. Structurally, though, it is like the "Taiwan monkeys" story.

Blood clams

Translated by William Wetherall

赤貝 (江戸小噺)

ある所に、大変利口な犬がおりまして、娘さんの言う事を大変良く聞くんですな。何か買い物がある時は、品物を見せて、首輪にぶら下げた袋にお金を入れますと、ちゃんとその品物を買ってまいります。すると、ここの親父は赤貝が好きで、これをサカナにチビリチビリやるのが、何よりの楽しみと言う。親父が「おう、赤貝がほしいな」ってぇと、娘が台所へ行き、犬に向かって何やらゴジャゴジャやっていますと、犬は、ザルをくわえて、小銭を持って出かけて行き、ちゃんと赤貝を買って参ります。母親が、どうやって教えるのかと、不思議に思って、こっそりのぞいて見ますと、娘は、自分の着物の前をパラッとまくって、自分のアソコを指差している。なるほどってんで感心した母親が、私もやってみよう、なんてんで台所に犬を連れてまいりますと、前を広げて見せます。犬はザルと小銭を持って出て行って、買って来たのが、「たわし」。

Blood clams (Edo story)

The family of a certain man in Edo had a very clever dog, which understood everything his daughter said. She could show the dog something, drop some coins in a pouch around its neck, then send it off to the market, and it would come back with exactly what she wanted. Her father liked succulent blood clams, and one day he said he wanted some for dinner. So his daughter went into the kitchen, muttered something to the dog, and sent the dog off to the market with a bamboo basket in its mouth. And sure enough, it came back with some fresh blood clams. The girl's mother, wondering how her daughter would get the dog to recognize blood clams, had peeked at her in the kitchen and seen her lift the front of her kimono and point to herself. So the next time her husband wanted blood clams, she imitated her daughter, but the dog came back with a bristly scrubbing brush.

Kobanashi draw from all aspects of life, including sexual anatomy. "Akagai" (red shellfish = blood clams) alludes to a girl's smoother pubes, "tawashi" (brush) to a woman's bristly pubes.

Art museum

Translated by William Wetherall

美術館

「まあ、素晴らしい絵。これはピカソね」

「奥様、それは鏡です」

Art museum

"Ah, such a wonderful painting. It's a Picasso, right?"

"Madam, that's a mirror."

A mirror figured in one of the jokes told by Daliso Chaponda in the 1st semi-final of Britain's Got Talent in 2017. A woman complains that a mirror makes her look fat, and Chaponda tells her his eyes have the same problem. Mirrors that warp a figure in various ways, making someone look fat or skinny, or creating the illusion of a narrow waist and flairing hips, or a head too large or too small, were featured at amusement parks like Playland-At-The-Beach just north of the west end of Golden Gate Park in San Francisco. The playland was between the park and the Sutro Baths and museum, which I also frequented when growing up in the Sunset District south of the park in my early teens during the early 1950s.

Beauty shop

Translated by William Wetherall

美容院

「おめかししてどちらかへ行かれたんですか?」

「美容院へ行ってきたんですよ」

「今日休みだったんですか?」

Beauty shop

"You're all dolled up. Where did you go?"

"To the beauty shop!"

"Was it closed today?"

This sort of joke could travel in any language.

Drug mecca

Translated by William Wetherall

覚せい剤入手場所

よく群馬県へ行って入手するそうです。常習(上州)と云って . . .

The place to get stimulant drugs

"It seems people are going to Gunma prefecture to get drugs. Saying its Jōshū . . .

"Jōshū" was the common name for the provence of Kōsuke (上野) domain. An earlier name for Kōsuke was Kamitsukeno (上毛野 Kamitsukenu), which is better known today by its Sino-Japanese name Jōmō (上毛). In 1871, the domains in the provence became 9 prefectures, and later that year 8 of these prefectures were consolidated into Gunma prefecture, which gained more territory 1876. As a regional name, "Jōshū" is written 上州, but the name is homophonous with 常習, which means habitual user. This is similar to the play some people have made on the name of my home town, Grass Valley, in California, as they associate "grass" with "marijuana" and imagine a cannibus paradise.

American continent

Translated by William Wetherall

アメリカ大陸

地理の授業で先生が 「花子、アメリカ大陸はどこにありますか?」

「先生、ここです」と地図で指を指した。

「正解です。じゃあ、太郎、アメリカ大陸を発見したのは誰ですか?」

「ハイ、花子です」

American continent

In geography class, the teacher says, "Hanako, where is the American continent?"

"Teacher, it's here," she said, pointing to it on a map.

"That's correct. Okay, Tarō, who discovered the American continent?"

"Ah, Hanako."

This joke, too, could travel anywhere.

Bride hunting

Translated by William Wetherall

嫁さがし

息子が結婚したい女性を連れてきた。お母さんは大反対。しょうがないので止めて、今度はお母さんとそっくりな女性を連れてきた。体型も性格も . . . お母さんは大喜び。お父さんが大反対。

Bride hunting

A son brought home a woman he wanted to marry. His mother was opposed so he gave up. The next time, he brought home a woman who was just like his mother . . . her figure, her personality. This time his mother was delighted, but his father was opposed."

Where in the world could you tell this joke, that people would not laugh?

What is marriage?

Translated by William Wetherall

結婚とは・・・

人生の墓場に例える方がいますが、世界一周豪華クルーズに似ているとも言われます。長い後悔の始まり . . .

What is marriage?

Some people liken marriage to the grave (tomb) of life, but it is also said to resemble an around-the-world luxury cruise. The beginning of a long regret . . .

This joke hinges on a pun that travels only in Japanese, and hence it is language-bound. The punch line "long regret" reflects "kōkai" (後悔), which is homophonous with a Sino-Japanese term meaning navigation, sailing, or voyage by sea -- i.e., "cruise" (航海). The Sino-Japanese word play is enhanced by the Japanese transliteration of English "cruise" (kuruuzu クルーズ), but the joke could be told without using the Anglo-Japanese word. Moreover, the written form of the joke would better emulate its oral form if "kōkai" were phonetically scripted in katakana (コウカイ), thus letting the reader puzzle out its possible meanings -- rather than graphically interpret them with kanji.

Divorce crisis

Translated by William Wetherall

離婚危機

「ウチの夫婦関係は治りかけの肺炎によく似ているんだよ」

「どこが?」

「もう熱はとっくに下がってはいるが籍が抜けないんだ」

Divorce crisis

"My husband-wife relationship is like recuperating from pneumonia."」

"In what way?"

"The fever has long dropped, but the seki doesn't leave."

This joke, too, is limited to Japan and Japanese. I've italicized "seki" in the punch line because the joke, when told orally, turns on "seki" meaning "cough" (咳) as a homonym with "seki" meaning "register" (籍). When writing the joke, it would be better to write "seki" in katakana (セキ), so the reader would have to figure out the play on the two "seki". The "seki" of "register" alludes to the legal fact that a married couple must share a common household register. When a couple marries, one spouse has to "enter the register" (nyūseki 入籍) of the other spouse. Divorce results in one spouse leaving the common register.

The world's shortest little story

Translated by William Wetherall

世界一短い小噺

天国の小噺 「あのよ〜」

The world's shortest little story

A short story of heaven "Ano yo"

"Ano yo" has the feeling of "Ano ne", which is used to get someones attention, or even to start a story. But it also "that (over there, yonder) world" or "the next world" -- hopefully "heaven" (tengoku 天国). There are numerous similar "shortest short stories" including 本当の話「実は (実話)」Real story "Jitsu wa (Jitsuwa)", and 旅行の話@「この度は (この旅は)」Travel story "Kono tabi (Kono tabi)".

The river Sanzu

Translated by William Wetherall

三途の川

ある80歳のおばあさんが突然水泳を習うと言い出しました。「おばあさん、いまさらなぜ水泳ですか」とお尋ねしました。するとおばあさんは、こう答えてくれました。「あの世に行くためには三途の川を渡らなければならない。その三途の川は舟で渡ることになっているが、それにはたくさんのお金がかかるそうだ。それで私は泳いで渡ろうと思って泳ぎ の練習をしています」

この話を伝え聞いたその家のお嫁さんは、水泳の指導員にこう言ったそうです。「すみませんが、うちのおばあさんにターンだけは教えないで下さい」

The river Sanzu

An old lady of 80 years suddenly said she was going to learn to swim. Asked "Why learn to swim at your age?" she answered, "In order to go to the next world, I have to cross the river Sanzu. There's a boat across the river, but it costs a lot of money, so I'm going to swim.

The old lady's daughter-in-law, hearing her mother-in-law's story, rushed to local swimming pool, where her mother-in-law was practicing, and told the instructor, "Please don't teach her how to turn."

This is, of course, a "mother-in-law" joke of fairly recent vintage, involving the idea of "turning" in swimming pool. Sanzu no kawa (三途の川) -- the river Sanzu -- "the river of three paths" -- refers to the river that, in some Buddhist views of life after death, the dead in this world (kono yo) must cross to reach life in the next world (ano yo). The deceased depart from "this bank" (shigan 此岸) on the side of their present existence and arrive at "the other bank" (higan 彼岸) on the side of their next exitence.

Awaiting them on the other side are several paths or ways (zu, michi 途), or roads or realms (dō, michi 道) of existence -- the hungry-demon realm (gakidō 餓鬼道), the beast realm (chikushōdō 畜生道), and the hell realm (jigokudō) 地獄道). Complementing these three "lower" realms of existence are three "higher" realms

-- the human realm (ningen-dō (人間道), the demigod realm (shūra-dō 修羅道), and the god realm (tendō 天道).

Some Buddhist funeral customs include placing coins in the coffin or grave of the deceased for ferry passage across the river. There are many other names for the river, deriving from early Chinese and Japanese perceptions of the divide between life and death and transmigration of the soul. The counterpart in Greek mythology is the river Styx, which people must swim if they have no coins for passage. There are many

Match factory in China

Translated by William Wetherall

中国のマッチ工場

マッチ工場が全焼した。焼け残ったのはマッチだけだった。

Match factory in China

A match factory burned to the ground. All that was left were matches.

This is an "ethnic" joke in that it hinges on stereotypes about the quality of Chinese products. "China" could be replaced with any country that was associated with inferior or defective products.