Unexpected Muteness

By Oe Kenzaburo

Translated by William Wetherall

A version of this translation appeared in

The Japan Quarterly, 36(1), January-March 1989, pages 35-44

See also Buffer Zones

Oe Kenzaburo, born in 1935, received the Akutagawa Prize for "Shiiku" in 1958, and the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1994.

"Unexpected Muteness" first appeared as "Fui no oshi" in the September 1958 issue of Shincho. It is currently available in Shisha no ogori / Shiiku (Tokyo: Shinchosha, 1959, pages 157-174), a paperback anthology of six Oe stories.

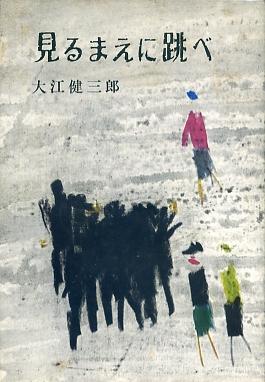

This translation is based on the version appearing in Miru mae ni tobe [Leap before you look] (Tokyo: Shinchosha, 1958, pages 105-125), an out-of-print hard cover anthology of five Oe stories. The story has also been translated into Korean (1964) and German (1975).

A jeep full of foreign soldiers raced through the fog at daybreak. A boy making the rounds of his hunting ground at the end of the valley, shouldering a loop of wire which ran through the wings of a trapped bird, saw it, and for a moment he held his breath and watched. It would take some time for the jeep to cross the high ground, fall into the dip, appear again on the high ground and come into the village in the valley. The boy released his breath and went back to the village. His father was the head of the small hamlet, and the boy returned pale to the place where his father was preparing to go out and till the fields. Ring the fire bell and call together all the people in the village to his father's house on the side of the hill overlooking the valley. Young women take shelter in the charcoal maker's shed on the ridge of the mountain; men bring everything that you fear would be mistaken for a weapon to a shed in the fields. Do not fight the soldiers. These instructions had been repeated and drilled many times. But the foreign soldiers had never come as far as the village in the valley. The children were excited and walked around on the short village road in the valley, and the adults, too, made little headway with their tilling, bee tending, and making fodder for the domestic animals. Then after the sun had become fairly high, the jeep came into the village in the valley very quietly at great speed. It pulled into the yard in front of the schoolhouse, which had been closed for the summer. Five foreign soldiers and a Japanese interpreter got out. They worked the pump in the yard, drank the always turbid white water and wiped their bodies. The adults and children of the village kept their eyes on them while ringing around them at a distance. The women and even the old folks burrowed into the gloomy, small earth-floor rooms at the entrances to their houses and never tried to go outside. When the foreign soldiers who had finished wiping their bodies returned to the vicinity of the jeep, the ring of village adults and children widened. They were thoroughly stirred at seeing the soldiers, of a foreign country, who had come to the village for the first time. The interpreter shouted in a loud voice, his expression stern. They were the first words of the morning. "Where's the hamlet head? Call him!" The boy's father, who had been watching the arrival of the foreign soldiers along with the other villagers, stepped out from the ring. The boy was moved to see his father proudly throw out his chest and answer the interpreter. "I'm the head," his father said. "We've decided to rest at this village until it cools off this evening. We won't disturb you. These men have different eating habits so you don't have to serve them anything. It'd just be wasted if you did. All right?" "You can rest in the schoolhouse if you'd like," the boy's father said magnanimously. "You folks get back to work. I'd like to rest too," said the interpreter. A brown-headed foreign soldier put his lips to the interpreter's ear and whispered something. "He said thanks for coming to greet us," the interpreter said. The brown-headed foreign soldier smiled joyfully. The adults, despite the interpreter's words, looked at the foreign soldiers and made no effort to withdraw. They and the children just sighed and stared at the foreign soldiers. "You folks get back to work," the interpreter repeated. "Everyone, let's return to work," echoed the boy's father. The adults finally scattered, but they looked back unresigned. They seemed ready to come again at the slightest pretext, and they appeared ill-disposed toward the interpreter. Only the children stayed behind. Though they were still apprehensive about the presence of the foreign soldiers, they backed away from the jeep a little and watched them. One of the foreign soldiers began washing the jeep with water he had drawn from the well. Another had gone to a window at the front of the schoolhouse and was smoothing his hair, blond and blazing in the sun. There was also a soldier with a gun. The children held their breath and kept gazing at him. The interpreter expressly walked over beside the children, and after looking around in all directions without smiling, he climbed into the driver's seat of the jeep. And so the children were able to watch these visitors from afar without the least bit sense of reserve. The foreign soldiers seemed gentle and well behaved. And they were splendid with their tall backs and broad shoulders. The children gradually tightened the ring and got closer to the soldiers to see them better. They weren't very frightening. When noon passed and it became hot, the soldiers went down to the river and found some deep places where they could swim. The children looked with wonder at the bodies of the naked foreign soldiers. The soldiers had very white skin and golden body hair that glistened in the sun. They were splashing water at one another and shouting back and forth in loud voices. The children were drenched with sweat, but still they quietly sat on the bank and watched the foreign soldiers. The interpreter came down and he, too, undressed, but his skin was yellowish brown, and moreover he had no body hair at all, and his entire body seemed slippery and dirty. Unlike the foreign soldiers, he covered his underbelly with his hands as he stepped into the water. The children roared with scornful laughter at the way the interpreter behaved. The foreign soldiers appeared to barely associate with the interpreter. When the interpreter went to join in the splashing, he met an immediate siege of foreign soldiers and retreated screaming, such was their relationship. The foreign soldiers wiped their naked bodies while making weird noises, then put on their trousers and shirts. When the children chased after them, as they returned on a run to the school grounds, the interpreter was not with them. After a while, a disconcerted interpreter came back barefoot. He was finding the hot, rocky road rough going, and the foreign soldiers and children together greeted the interpreter's bent figure with laughter. The interpreter, though, wore a serious expression that was anything but a laughing matter. He appeared to be explaining the situation to the foreign soldiers. Hearing his story, the foreign soldiers again resounded in loud laughter, and the children opened their throats full valve and laughed happily. The interpreter came closer to the laughing children. His sullenness was clear at a glance. He spoke in a tone that seemed to scold the children. "You kids know where my shoes are?" he asked while flapping his bare feet. "My shoes are gone." The children cheerfully laughed. The interpreter, screwing his small, swarthy face in displeasure, was quite a spectacle. "Don't laugh!" the interpreter shouted in a high-handed manner. "One of you kids playing a trick on me? Hey! What about it!" The village children stopped laughing, swallowed their saliva and looked up at the interpreter. The interpreter addressed the children with a frustrated look on his face. "Look, has anyone seen them?" No one replied. Everyone's eyes were looking at the interpreter's long, white bare feet. They looked frail and disgusting, unlike the feet of the village people, who never wore shoes. "None of you know?" the interpreter asked in an angry voice. "You birds are useless!" The foreign soldiers had gone under the eaves of the schoolhouse to avoid the hot sun, and from there they watched the exchange between the interpreter and the children. They appeared to be enjoying the interpreter, whose dark clothing and bare feet exhibited a strange contrast. "Call the hamlet head. Tell him to come immediately," the interpreter said extremely tensely. The hamlet head's son left his friends and dashed up the steep rocky road through the woods. His father was sitting in the gloomy, earth-floor room with his mother, and they were sorting dried bamboo strips and tying them in small bundles. It was not the most suitable work for his powerfully-shouldered, thick-necked father. But in the boy's village it was impossible for the men to always do men's work. And conversely there were times when the women had to do men's work. "What?" the father replied in a hoarse voice to the boy's hail. "The interpreter's lost his shoes," the boy said. "And he said to come down." "How should I know," his father said, ill-humoredly. "How should I know about that filthy man's shoes!" But the father stood up and followed the boy outdoors, narrowing his eyes in the blinding sunlight. They went down into the valley. The village adults had gathered around the jeep in the open space in front of the school and were listening to an explanation about the interpreter's shoes. The interpreter eloquently repeated his speech for the benefit of the hamlet head who at length arrived with sweat on his brow. "My shoes were stolen while I was swimming. What happens in your village is your responsibility. Get them back." Before replying, the boy's father looked around at the villagers. His father then slowly refaced the interpreter and shook his head. "What?" the interpreter said. "It's none of my concern," the father said. "They were stolen in your village!" the interpreter persisted. "Your village is responsible." "Who knows that they were stolen?" said the father. "They might have been swept downstream." "I put them on the sand with my clothes. I'm certain of that. There's no way they could have been washed away." The father looked around again and spoke to all the adults and children. "Any of you people steal his shoes?" Then he spoke to the interpreter. "Seems not." "Don't be fooled by the kids," the interpreter said, excitedly. His thin lips were very slightly trembling. "Don't underrate me!" The father remained silent. The interpreter spoke again. "Those shoes are military issue. Do you know what happens to people who steal or conceal military property?" The interpreter looked behind him and raised his arm, and in response to this, the splendidly tall, golden and chestnut haired men came over from the schoolhouse and drew around the interpreter and the father. The father was completely hidden among the broad, high shoulders of the foreign soldiers. For the first time the foreign soldiers had slung their short, massive rifles in a way such that the butts struck hard against their hips. The ring of foreign soldiers loosened, and the father poked his face out and spoke in a loud voice. "First we're going to search around the river. Please help." With the interpreter and the father in the lead, the foreign soldiers, and the adults and children of the village, walked toward the river. The children were excited, and they tagged along while tromping daringly into the clumps of ferns. Searching along the short river bank was a very simple task. But except for the interpreter, no one committed themselves to it. Among the foreign soldiers, a very young man with freckles readied his rifle at his waist and aimed at the branches of a paulownia tree. On one of the branches was a gray bird that had just flown from the opposite bank and was puffing up its chest. The bird remained still, but the foreign soldier didn't fire. When he lowered the barrel of his rifle, and began running his eyes along the edge of the river in search of the shoes, the village adults and children all sighed in relief. The people of the village had come to feel as though they had all been liberated from their tension toward the foreign soldiers. But when the interpreter raised his angry voice from a clump of grass a fair distance from the river bank, indicating that he had found the strings to his shoes and that they had been cut with a sharp blade, an awkward feeling mixed with fear returned to the people of the village. The children backed away into the thick growth of bamboo grass and weeds, and ferns. The interpreter shouted something in a foreign language, and a brown-headed, thick-chested soldier approached him with great strides. The interpreter pointed out the part of the shoestring that had been cut and pointed out the distance from the river bank with his finger. The village head, oddly frowning, listened to this, but he did not understand the foreign language and was merely absorbed in thoughts about something else. The soldier slowly nodded and looked around at the village adults. Then the interpreter began to speak with a force that stormed at the father. "There's a thief among the people of your village. You know who, don't you? Make him confess!" "I don't know," the father said. "No one steals things in this village." "That's a lie! You think I'm going to be deceived or something?" the interpreter said abusively. "People who steal military property will be shot to death. You got that?" The father showed no reaction. The interpreter, sternly twitching his eyebrows, glared at him. The brown-headed foreign soldier said something to the interpreter in a very ordinary voice. The interpreter nodded in reply but remained sullen. Thereupon they withdrew to the yard in front of the school. The figure of the interpreter walking barefoot up the sun-baked road was most comical. While walking as though he were hopping, the interpreter repeatedly wiped the dirty sweat from the scruff of his neck. At the open space in front of the school, the interpreter, after talking with gestures to the brown-headed soldier, spoke in a tone that clearly sought to jolt the hearts of all the village adults. "We are prepared to forcibly search your homes." He said this with strength. "The person who is concealing the shoes will be arrested. But if that person has the mind to voluntarily produce the shoes and apologize, we will let the matter pass." The people of the village didn't stir at all. The interpreter grew more irritated. "Hey, kids, any of you see the person who hid my shoes? If you did, come and tell me. I'll give you a reward!" The children were silent. Again the interpreter, gesturing furiously, talked with the foreign soldier. The soldier nodded with apparent resignation, and when he had withdrawn into the school, the interpreter tossed his sweat smeared head and spoke. I'm going to search all the houses. The person who has stolen and concealed military property and remained silent will be punished." Then he gave them a direct order. "Follow me! I'll search from the northern perimeter in the presence of everyone. No independent activities are permitted until the items are found." Not one of the village adults made an effort to move. The interpreter raised his voice. "What are you standing around for!" he screamed with a force that flew at the villagers. "I said, Follow me! Or do you intend not to cooperate?" His voice was futilely sucked up into the scorching sky, and the village men just stood their folding their sweat gushing arms. The interpreter, convulsed with anger, fully opened his feverish eyes and stared in every direction, shaking his entire body. "Follow me! I'm going to search your houses one by one!" "Come on, let's go and watch," the father said. At this the village men followed the interpreter and walked toward the north side of the valley. It was the time that the sun struck the valley most fiercely. The raging, barefoot interpreter, while suffering the heat of the rocks that covered the road, walked headlong in his comical way, which brought laughter to the children who saw him off. The foreign soldiers also emitted an embarrassed laughter. With this the children quickly regained their friendly feelings toward the foreign soldiers. The foreign soldiers, unable to depart while the interpreter's search was being conducted, walked idly around the jeep or stayed in the school. The children had a happy time keeping their eye on these foreign soldiers. The foreign soldiers, curious about a small girl dressed in a kimono, took pictures and wrote in their notebooks. But as the search dragged on, they tired of this. The interpreter very obstinately continued the search. The foreign soldiers stepped onto the plank floor of the school building with their footwear on and waited, sprawling out or sitting down. They seemed bewildered. Among them was a young soldier who incessantly moved his jaw, and now and then he would spit some peach-colored sputum on the sun-parched, dusty ground. The adults, following the interpreter, observed the search of each house, but the children crowded into the yard in front of the school and looked at the jeep, and looked at the disgusted soldiers. They watched enthusiastically without getting bored. A young soldier tossed them some of the paper-wrapped candy he was chewing. The children ate it while smiling ear to ear and leaping with joy, but the sticky candy clung to their teeth, and it was difficult to chew, like leather. All of the children spit it out, but they were fully satisfied. Unexpectedly the sun darkened and the mountains enclosing the valley became black, and the wind picked up and stirred the grass in the groves of chestnut trees. It was dusk. And at last the exhausted interpreter, bringing along the village adults, gloomily and silently returned to the yard in front of the school. His bare feet, dirty with sweat and dust, seemed to be wrapped in a black cloth, and nothing could have been bigger or uglier. He appeared to be explaining the situation to the foreign soldiers who were in the schoolhouse. There was no longer any laughter among them. They looked weary of waiting, exasperated. When the foreign soldiers came out into the yard with their rifles in their arms, the interpreter, with them backing him up, refaced the village adults. "Please cooperate!" His voice had become imploring. "Cooperating with me is cooperating with the occupation army. From now on, Japanese people will not be able to proceed in life without cooperating with the occupation army. Are you not the people of a defeated country? You are in no position to complain even if you are massacred by the people of the victorious country. Would it not be sheer madness not to cooperate?" The adults silently watched the interpreter. The interpreter, while irritably thrusting a finger at the boy's father, returned to his earlier forceful voice and shouted. "We will not leave this village until you return my stolen items. All I have to do is tell these soldiers that some defiant people have weapons and are concealing them, and they will stay in this village and begin an investigation. And if they stay here, the wives and daughters you've sent to the mountains aren't going to get off free." The interpreter, as though to confirm that the villagers were trembling, gravely pursed his lips and glared around. "Okay. You still intend not to cooperate?" "I told you that no one here knows anything about your shoes. I said that they must have been washed into the river," the boy's father said with great patience. "It is not a matter of cooperating or not." "You bastard!" the interpreter shouted, baring his teeth, and all at once he hit the father right in the face. The father remained undaunted as he steadied his sturdy jaw, but his lip was cut and some drops of blood began to trickle. And the boy looked up, gripped by an anxiety that tightened his chest, and saw his father's sun-tanned cheeks slowly start to redden. "You bastard!" the interpreter repeated, breathing hard. Your the hamlet head, it's you're responsibility. If you don't tell me the name of the thief, I'm going to tell the soldiers that you're the thief. And I'll have them arrest you and turn you over to the occupation army police." The boy's father slowly turned around, and he began walking away with his back to the interpreter. The boy sensed that his father was seething with anger. The interpreter tried calling him back in a loud voice, but the father walked steadily on and showed no response to this. "Stop, you thief, don't run away!" the interpreter shouted. And after this he exclaimed something in a foreign language. A young soldier dashed out, his rifle ready. He yelled, of course in a foreign language. The father glanced back, then began running as though suddenly seized by fear. The interpreter shouted, and then the young foreign soldier's rifle sounded a report, and the father threw out his arms and floated his body through the air as though flying, and fell that way to the ground. The people of the village raced to his side. The boy had dashed to his fallen father ahead of them. The father gushed blood from his eyes, nose and ears, and he was dead. The boy, convulsed in sobs, buried his face into his father's seemingly feverish back. He alone possessed his father. So the other villagers looked back, and they stared through the thick dusk air at the interpreter and foreign soldiers who were standing there dumbfounded. The interpreter, who had stepped a couple of paces away from the foreign soldiers, called out in a frenzied voice, but not one of the village adults or children replied. All of them just stared at him in silence. The night deepened, and only the boy and his mother were beside the sturdy corpse that laid on the floor. The mother hunkered like a man, embracing her knees with her arms, her body not moving. The boy gazed down from the window facing the valley, and he too was motionless and silent. A thick fog rose from the river on the floor of the valley. The boy, straining his eyes, watched the adults climbing up the rocky road from the village, and the fog slowly moving toward the top after them. The adults climbed slowly and silently. They planted their feet very firmly, as though they bore heavy loads. The boy, biting his lips, his pulse racing, stared at them. They climbed very slowly, but steadily. The boy seemed about to lose consciousness. Then, suddenly, his mother crawled over and peeked out the window. He sensed that his mother was watching the adults. His mother wrapped her arms around his shoulders. The boy stiffened his body in his mothers arms. No sooner had the adults disappeared behind a stand of oaks that, without greeting they pushed open the wooden door passing to the earth- floor room of the boy's house, and at once they crowded into the entrance and silently stared at the boy. The boy felt his mother, who was embracing him, start to tremble, and immediately he was infected by this and he too began to quiver. But he freed his body from his mother's arms and stood up. And he stepped down into the earth-floor entrance still barefoot, and he began walking, surrounded by the adults. The adults quickly descended the steeply inclined, fog-dampened road, and the boy tripped along while shivering from fear and the coldness of the fog. The road forked at a level place in front of a small quarry, which had been opened in order to get limestone. After crossing an earthen bridge it led toward some stone steps that went down to a deep place in the river. There the adults' destitute and insidious faces, covered with unkempt beards, looked down at the boy while they twisted from tension. They stared at him in silence. The boy embraced his body in order to check his shaking, then he ran alone toward the yard in front of the school while feeling that he was being watched from behind by the adults. The jeep rested quietly in the soft light of the moon. The boy stopped in front of it. The soldiers were probably sleeping in the schoolhouse. The boy stared at the jeep, his oral cavity filling with sticky sputum. A man's figure abruptly sat up in the driver's seat. It opened the door and got half out. "Who's there!" the interpreter's voice said. "What are you up to!" The boy was silent. Then he looked up at the interpreter's blackish head. "Do you know where my shoes are hidden?" the interpreter asked. "You want to tell me and get a reward?" The boy set his cheeks, then with all his might he turned his face upward. And he was silent. The interpreter sprightly jaunted out of the jeep. He slapped the boy's shoulders. "You're a good kid! Now take me to them. There's nothing to worry about, I won't tell the adults." The boy and the interpreter walked back the way the boy had come, side by side, jostling one another's bodies. The boy was pressing the limit of his will so as not to arouse suspicion with his trembling. "What kind of reward shall I give you?" the interpreter spoke loquaciously. "Hey, what do you want? Shall I get the soldiers to give you some candy? Have you ever seen foreign picture postcards? I can even give you a magazine that foreigners read!" The boy just held his breath and walked in silence. The stones hurt the soles of his bare feet. It seemed more painful for him than for the interpreter, who lightly hopped along while cheerfully talking. "You a mute or something?" the interpreter asked. "Even a mute can understand things, huh! But the adults in your village, something's wrong with their heads." They came to the front of the quarry. They crossed the earthen bridge and descended the stone steps, which were wet and slippery from the fog. Unexpectedly some arms came out from the darkness under the earthen bridge and covered the interpreter's mouth. And the bodies of several adults, coarse hair growing all over them and muscles bulging hard like stone, surrounded the interpreter, exposing their withered sex organs. The interpreter was seized by the naked bodies so that he could not move, and he was slowly submerged in the water. Those whose breathing became difficult released the interpreter's body and thrust their faces above the surface of the water, took a breath, and again dove down and took hold of the interpreter's body. For a long time the adults repeated this operation, surfacing at turns, and then they came up to the stone steps, leaving only the interpreter in the deep place of the water. They all shivered in the cold. After vigorously shaking their bodies and throwing off the water, they put on their clothes. The adults saw the boy to the beginning of the grade. Then, as though he were being pursued by the sound of the their footsteps when they silently went back, the boy ran up through the woods at dawn. When he opened the door, the soft, blue-gray dawn fog came pouring in from the open door, and it caused his mother, sitting with her dark back facing the earth-floor entrance, to cough. He, too, coughed as he stood in the earth-floor entrance. His mother looked around at him with truly angry eyes. He silently stepped up on the board floor and stretched his shivering, goose-pimpled body out on a corner of the mat already half-occupied by his father's large body. His mother's gaze crept around his narrow back and slender neck. He sobbed without raising his voice. He was tired out and torn by a sense of inertia, and more than all he was seized by a powerful fear. His mother's hand touched the nape of his neck. He violently shook it off as though crazy and bit his lips. His tears flowed. The vigorous cries of a small bird rose from the mixed forest with chestnut trees that stood just behind the house. In the morning, one of the foreign soldiers found the interpreter floating in the deep place in the river, his white feet both sticking out of the water. He roused his buddies and told them about it. They tried to get some people of the village to pull the interpreter from the river. But the children never came close to them, nor was there any sign that they were watching them from a distance. The adults were tilling their fields, repairing their bee hives and cutting grass. Even when the foreign soldiers expressed their intentions with gestures, the adult villagers showed not the slightest reaction. And they proceeded with their work, seeing the foreign soldiers as though they were trees or pavement stones. Everyone worked in silence. It was as though they had completely forgotten that there were foreign soldiers in the village. At length one of the foreign soldiers stripped off his clothes, went into the river, and retrieved the drowned corpse. It was carried up to the jeep. Throughout the morning, the soldiers sat or walked around the jeep. They looked irritated enough to die. Then, unexpectedly the jeep turned around and headed out of the village the same way it had come in. The village people went about their quite everyday tasks, not one of them, including the children, paying it any attention. Where the road passed out of the village, a small girl was fondling the ears of a dog. The foreign soldier with the clearest blue eyes tossed them a piece of wrapped candy, but the girl and dog continued their play, neither of them making a move to get it. |