Meiyo shinbunNew tidings of honor and glory

Yoshitoshi, Hakuen, and Watanabe:

How old stories vied with new By William Wetherall

First posted 7 Feburary 2008

Illuminating topics |

||||||

Illuminating topics

Gusokuya's 1874 Meiyo shinbun / shindan series is valuable for the light it sheds on several interesting topics: (1) ties between the artisans who plied for a living in the contemporary publishing industry, (2) the parameters of "news" (新聞 shinbun) as a term used to characterize printed matter, and (3) the state of scholarship in present-day studies of news-related woodblock prints.

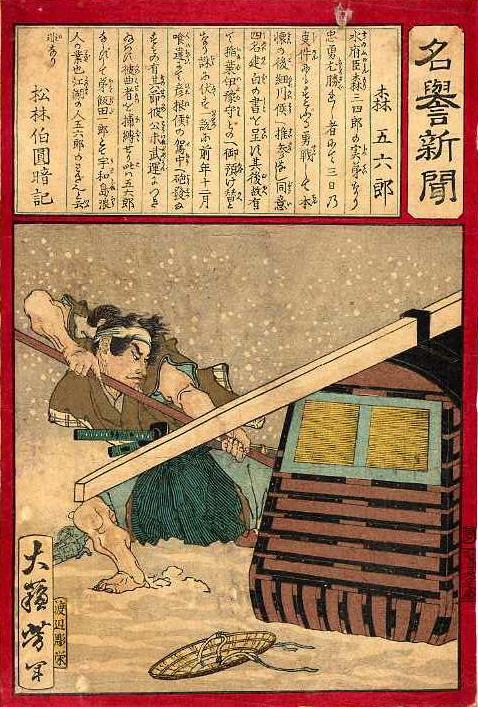

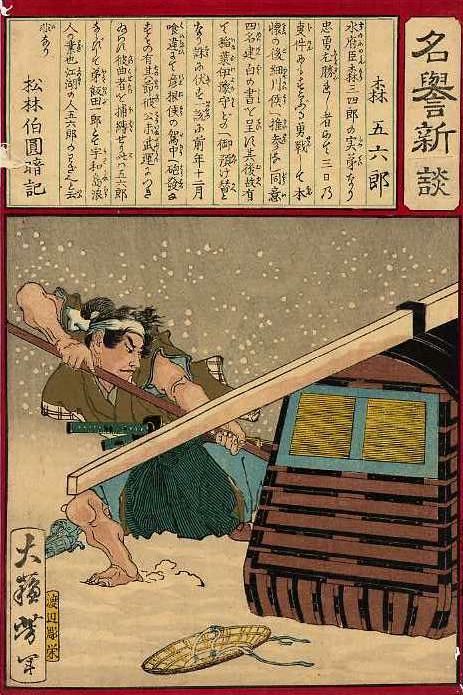

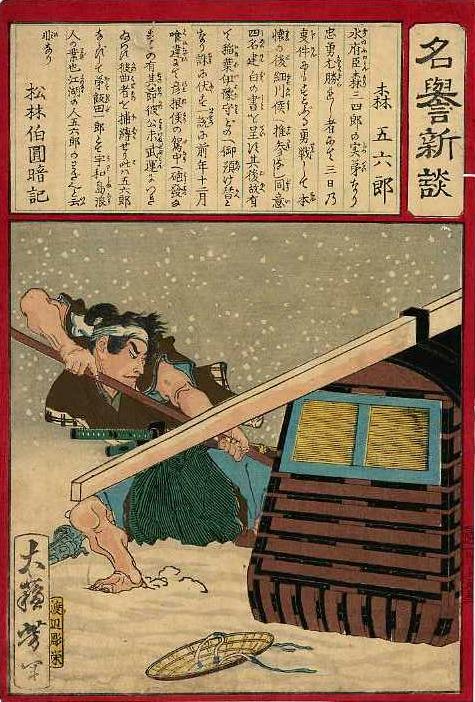

The Meiyo prints -- as I shall call them, regardless of their "shinbun" or "shindan" titles -- were drawn by Taiso Yoshitoshi, written by Shorin Hakuen, carved by Watanabe Horie, and first published by Gusokuya (Fukuda Kumajiro) in October, November, and probably also December 1874.

The name of the Meiyo series changed from Meiyo shinbun -- meaning "New tidings of honor and glory" -- to Meiyo shindan -- or "New stories of honor and glory". This change appears to have occurred during or after the summer of 1875, as a result of newpaper-publisher objections to the use of "shinbun" on prints featuring incidents which had taken place several years before, which ran counter to the intention of "shinbun" to refer to "news" or current events.

The world of artisans

"Meiyo shinbun / shindan" (MSb/MSd) was published by Gusokuya during the same period in which he was putting out Yoshiiku's Tokyo nichinichi shinbun (TNS) nishikie series, most of which were carved by Watanabe. Late 1874, when most if not all of the Meiyo prints were published, was in fact the busiest period for the TNS series.

Kinshodo began publishing the rival Yubin hochi shinbun (YHS) nishikie series from February the following year -- contracting Yoshitoshi to draw them, and several narrators -- including Hakuen -- to write the accompaning stories. Watanabe Horiei and Katada Horicho, another carver of Yoshiiku's TNS drawings, cut the blocks for a few of the early YHS prints.

The publishing world was one in which drawers and writers had brushes and travelled. Carvers, too, were known to share their talents with more than one publisher. They were essentially hired hands, and the blocks belonged to the publishers, who continued to make impressions as long as there was a market, or until the blocks were too worn or irrepairable.

At times parts of some of the blocks had to be repaired, or recarved on account of changes in the text, or in the case shown here, changes in a single character in order to comply with a new regulation.

The part of a block that required recarving was chisled from the original block, and replaced by an inset or inlay, called an "ireki" (入れ木), that was carved (if not pre-carved) to reproduce the original design if merely damaged, or a new design, text, or character if that was the purpose of the inset.

The parameters of "news"

Forthcoming.

Limitations of scholarship

The study of woodblock prints depends entirely on the ability to examine prints in their natural setting. The study of early Meiji news nishikie is limited by ability to (1) discover prints, and (2) reconstruct the conditions in which the prints existed.

Discovery is a matter of finding, by design or accident, prints that have survived time. Some of the prints I have shown here were found as a result of diligent poking around in publications, shops, and websites -- knowing, and sometimes finding, what I was looking for. Other prints were discovered in the course of looking for something else.

Reconstruction is more a matter of setting aside the prejudices and fashions of here-and-now ideology and theory, in order to understand what life might have been like for those who had to live it then and there. For me, "reconstruction" is a matter of analyzing the content of what has been discovered for what it reveals about the content of contemporary life.

Scholarship is about the study of things -- but scholars can only study what they know or suspect exists -- and hence they study only what falls within their range of vision, within accessible territories.

When it comes to the study of Japanese woodblock prints, there are -- very broadly speaking -- two communities of scholars, each working in its own territory -- one in Japan, the other in Euroamerica. Scholarly writing in Japanese and English, about the Meiyo prints for example, shows that -- not only do these language twains seldom meet, but scholars working within these linguistic worlds often fail to discover material because their terrains are full of hidden valleys and caves that the casual explorer will never find.

I say "casual" because most scholars who have written about the Meiyo prints have mentioned them only in passing, as objects which appear in their peripheral vision, as they focus on other prints.

Keyes 1982 on Meiyo series

Roger Keyes, in Courage and Silencej: A Study of the Life and Color Woodblock Prints of Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, his doctoral dissertation (see review in "Bibliography"), catalogs the Meiyo prints as two works -- "Meiyo shimbun" (No. 309, page 401) and "Meiyo shindan" (No. 318, page 409).

|

309. Meiyo shimbun 名誉新聞 1874 The newspaper of glory. (YK) Ōban series (?). Probably published by Gusokuya as a predecessor to Meiyo shindan, number 318. 名誉新談 318. Meiyo shindan 名誉新談 7 or 10 1875 New tales of honor. Ōban series (13). P: Gusokuya. E: Watanabe Hori Ei. Texts by Matsubayashi (Shōrin) Hakuen).

|

Keyes did not indicate which prints he had personally confirmed. He refers only to a "secondary source" coded "(YK)" -- which he describes as "Yamanaka Kodō. An extensive, but perfunctory and unreliable checklist of titles of Yoshitoshi's sets in prints arranged by format in chronological order" (Keyes 1982:336).

While Keyes is aware of the limitations of collating imperfect secondary information with confirmed primary information, his own perfunctory treatment of the Meiyo series, among others, has perpetuated misinformation in numerous mentions of the series by writers who have taken his authority for granted.

van den Ing and Schaap 1992 on Meiyo series

The catalog of the 1992-1993 Beauty & Violence Yoshitoshi exhibition (van den Ing and Schaap 1992), following Keyes 1982, calls the series "New tales of honour" (Meiyo shindan). It lists the same 13 prints in the same order, and repeats essentially the same blurbs, while adding brief profiles of the men on nine of the prints (van den Ing and Schaap 1992:115).

The catalog shows black-and-white images of two of the prints -- No. 8 (Kondo Isami), owned by the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and No. 13 (Hirose Kazuma), from the collection of its co-editor Robert Schaap.

The catalog also notes that "The series title [for No. 12 (Iba Hachiro)] reads Meiyo shinbun."

The "scholarship" reflected in the "Beauty & Violence" exhibition -- held at the Van Gough Museum in Holland, the Kunstmuseum Dusseldorf in Germany, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art in the United States -- was limited by the "vision" of the Euroamerican institutions, curators, and collectors that enabled its mounting.

This limited "Euroamerican" vision did not extend to published catalogs of earlier exhibitions in Japan which featured Meiyo prints and editions not listed by Keyes -- such as the "Shinbun nishikie: Bunmei kaika no jikenbo" exhibition held at four museums in Japan in 1988-1989 (Itabashi-ku 1988, reviewed in "Bibliography").

Linhart 2005 on "Meiyo shinbun"

Sepp Linhart, in "Shinbun nishiki-e, Nishiki-e shinbun: News and New Sensations in Old Garb at the Beginning of a New Era" (Formanek and Linhart 2005), follows Tsuchiya 2000 (Bunsei Shoin CD-ROM) in referring to "five prints by Yoshitoshi with the title Meiyo shinbun" (Linhart 2005:348)

|

[Tsuchiya's] CD-ROM contains a third category called fringe materials (shūhen shiryō), which is again divided into three subspecies: a group of prints similar to nishikie-e shinbun, a cond one of newspaper-like prints that are devoted to one event only, and a third group of miniature newspaper prints. Group one includes prints which, although they have the word shinbun in their title, treat persons and events without any news value, because they happened years ago, such as the five prints by Yoshitoshi with the title Meiyo shinbun 名誉新聞, published in October and November 1874 by Gusokuya. |

Apparently Linhart did not notice that, while Tsuchiya's article stated five prints, her table of data on known prints listed only four. He also appears not to have noticed that, of the four prints shown in Tsuchiya's image database, two are "Meiyo shindan" editions.

Tsuchiya 2000 "Meiyo shinbun" prints

In her CD-ROM article, Tsuchiya writes this about the series (page 27, my translation).

|

5. Peripheral materials A. Group resembling nishikie news (1) "Meiyo shinbun" (ōban, vertical) Series that is similar to [nishikie news prints] in that its format uses a red margin, and writes text in a separate frame at the top, but which depicts loyal-to-the-king [emperor] dedicated-men of the bakumatsu [period] (幕末の勤王志士), such as Kondo Isami, Takeda Kousai, Mishima Saburobee, Mori Gorokuro, and So Gessho. The publisher was Gusokuya of Tokyo, the drawings were by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, and Shorin Hakuen signed the stories. Published in October and November 1874. No series number, and there are some with "Meiyo shindan" titles. As of now, five have been confirmed. |

Tsuchiya did not list, or show, the Mishima Saburobee print -- which was shown and fully transcribed, with the Takeda Kounsai print, in the 1988-1989 "Shinbun nishikie: Bunmei kaika no jikenbo" exhibition catalog (Itabashi-ku 1988:122).

Itabashi-ku 1988 "Meiyo shinbun" prints

The 1988-1989 exhibition catalog shows two Takeda Kounsai and Mishima Saburobee prints last among several prints its groups at the end of the catalog under the heading "Later news nishikie: News supplements" (その後の新聞錦絵:新聞付録). Most of the prints shown in this section were indeed distributed as supplements with newspapers (Itabashi-ku 1988:117-122).

The compilers of the 1988-1989 exhibition catalog present absolutely no evidence that the two "Meiyo shinbun" prints -- the very last to be shown -- deserve to be classified as "news supplement" prints. In fact, they were published before newspapers are known to have distributed nishikie supplements.

Civil war nostalgia

Linhart had more to say about the Meiyo series. In the following remarks -- made immediately after the above-cited reference to Tsuchiya's mention of five prints -- he offers his own opinion of why series was published (Linhart 2005:348).

|

This series apparently aimed at making profits from the vogue for nishikie-e shinbun at the time, but it actually dealt with stories of young heroes fighting for the Tenno in the bygone Bakumatsu upheavels. |

Linhart paraphrases Tsuchiya's characterization of the heroes depicted on the Meiyo prints -- apparently without understanding that it was not quite correct, even for the prints she claimed to know. And without any help from Tsuchiya, he called them "young" -- though a couple of the men on the prints she shows were anything but young.

Kondo Isami (1834-1868), best known as the leader of the Shinsengumi, whose main function was to protect the Tokugawa government against radical elements in Kyoto, was 33 when he was executed in Itabashi, on the outskirts of Edo, in the spring of 1868. Kondo had surrendered after losing a battle with the new "government army" which the Satsuma/Choshu alliance had formed after it had overthrown the Tokugawa shogunate in late 1867 and "restored" the emperor to power by early 1868.

Takeda Kounsai (1803-1865) was at least 61 when executed after surrendering, with his supporters. He had been retreating to the west, with followers and his "other woman" Tokiko, through snow-bound mountains, after a failed rebellion within the Tokugawa domain at Mito. Takeda, a senior Tokugawa official, had founded a faction called the "Heavenly dog party" (天狗党 Tengutō). The party sought to protect the purity of the "national body" (国体 kokutai) by "revering the emperor and exorcising barbarians" (尊皇攘夷 sonnō jōi) -- in opposition to the policies adopted by the Tokugawa government, whose controlling factions had been accommodating Euroamerican demands for extraterritorial concessions in treaty ports.

Mishima Saburobee

Mori Gorokuro

So Gessho (1813-1858) was pushing 45 -- hardly young in days when people lived an average of 40 and 50 -- when he ended his life. Priest (So) Gessho, the head of a temple associated with Kiyomizudera in Kyoto, fled to Kagoshima with Saigo Takamori to escape a purge of anti-Tokugawa forces. Saigo, unable to secure the refuge he promised, proposed they die together, and the two men jump into the Satsuma sea. Gessho drowns. Saigo survives to fight another day.

The first Meiyo shinbun prints were published by Gusokuya during the last three months of 1874 -- when Gusokuya was at his busiest cranking out the TNS news nishikie series. This may explain why the series was initially called "Meiyo shinbun" rather than "Meiyo shindan" -- though Linhart does not point this out. It would not, however, explain why later prints in the series, or later reissues of earlier prints, were styled or re-styled "shinbun".

Linhart observes that 1874 witnessed a rush of prints by many publishers memorializing the warriors who fell in the civil wars that brought about the Meiji Restoration. The prints were particularly popular that year because it marked the important 7th-year memorial of the Battle of Ueno Hill, fought in the heart of Edo in 1868 on the eve of the Meiji Restoration, among other conflicts that led to the end of the Tokugawa shogunate.

TNS 689 portrays two of the Shogitai heroes who fell in the Ueno battle. The story on this print is mostly an advertising by its writer, Takabatake Ransen, who very candidly admits that he and a co-author hope to profit from their collection of war stories, which they had published that spring in time to ride the wave of nostalgia energized by the widely publicized memorial services at Ueno, among other memorial events.

The heroes depicted on the Meiyo prints were not all young, were not all fighting for the restoration of the emperor, and the upheavels that brought the Edo period to a close were far from over. Several of the heroes memorialized in the Meiyo series were Shinsengumi, Shogitai, or other passionate defenders of the Tokugawa order that crumbled under the might of imperial restorationists.

Most of the Meiyo heroes were dead -- as heroes tend to be. But one -- Enomoto Takeaki (1836-1908) -- had that very year, in 1874, been made a vice-admiral of the imperial navy.

Tsuchiya 2000

RESUMEREWRITE patterned variation of the sort we have seen in the titles of certain Osaka news nishikie series (particularly Series 23) -- but I think not. Far more likely, sometime during the run of the Meiyo series, Gusokuya decided to name a few of the prints "shinbun" rather than "shindan". My foundation for this view is a weakly impressed "bun" on one of the prints -- a "bun" that has every appearance of having been inserted in place of "dan" when it came time for reprints.

For a full discussion of the suppression of "shinbun" on news-related woodblock prints in Osaka, with images of examples of all methods of suppression, see Osaka news nishikie: "Shinbun" suppression.

Ansei purge

On the 3rd day of the 3rd month of the 7th year of Ansei (24 March 1860), Ii Naosuke (井伊直弼 1815-1860), the lord of Hikone, one of the highest officials of the Tokugawa government, was assassinated in his palequin at the Sakurada gate of Edo castle. In 1858, at Shimoda, representing the Tokugawa government, Ii had signed a treaty of "amity and commerce" which gave the United States extraterritorial rights, setting a precedent for similar treaties with several other foreign states. Ii's killers, a band of mostly Mito samurai, resented the Tokugawa government's policy of opening up the country to aliens, especially under unequal terms.

Members of the band included, among several others, Mori Gorokuro, Saito Kenmotsu, Ozeki Washichiro, all from Mito, and Arimura Jizaemon from Satsuma.

Arimura was wounded and killed himself. Saito died of wounds. Mori and Ozeki were executed after giving themselves up at the residence of a Tokugawa minister.

Ii had manipulated the imperial court in Kyoto to approve his signing of the treaty. This angered those within the Tokugawa government and the imperial court, and others who opposed giving in to the demands that various Euroamerican states had been making for trade concessions.

After concluding the Harris Treaty with the United States at Shimoda in 1858, Ii attempted to purge Tokugawa and court officials and others opposed to giving foreign states, if not also foreigners, a foothold in Japan. The purge is known as the "Ansei purge" -- after the name of the Ansei era.

The name of the imperial era was changed from Kaei to Ansei from Ansei 7-11-27 (15 January 1855). The name was changed because the last years of Kaei had witnessed the arrival of Commodore Perry's black ships in Edo, then a fire and earthquake. The name change, though, was to no avail, for an even greater earthquake -- known as the Great Ansei Earthquake -- struck Edo on Ansei 2-10-2 (11 November 1855).

Ansei became Man'nen from Ansei 7-3-18 (8 April 1860) -- about two weeks after Ii's assassination. Again, the name change failed to bring about better times for Edo, much less Japan. For despite the deaths of Ii's assassins, their success in ending his reign of suppression encouraged those he had driven underground to openly resume their effots to overthrow the Tokugawa government.