Dramatis persona

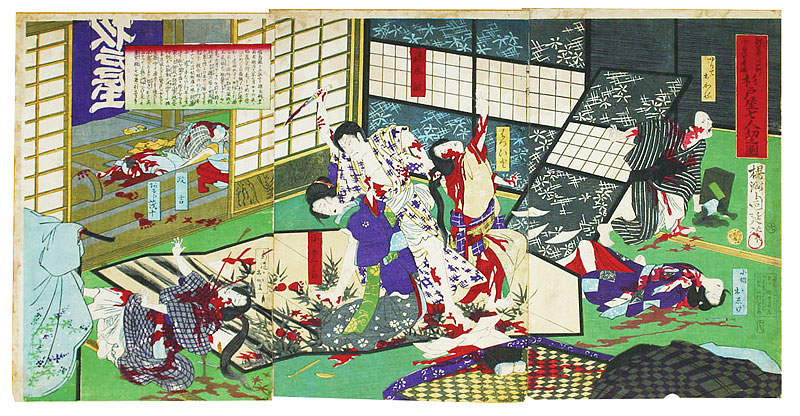

All victims and the culprit are identified by name cartouches. From top to bottom and right to left, for each sheet from right to left, they are:

Yarite Okano -- "Doer" Okano, the 30-year-old veteran courtesan entertainer who oversaw the younger women

Koaikata Oshige -- "Little courtesan" Oshige, not identified in story but apparently a young prostitute in training

Tokunaga Bin -- the disgraced and resentful shizoku from Fukushima, 28 years old according to the Kunimasa version, running amok, making a nuisance of himself and a bit of a mess

Hatsuito -- the 16-year-old courtesan entertainer who was Tokunaga's accompanist and first victim, according to the story

Kozakura -- a courtesan entertainer -- just out of the tub according to the story here -- 23 years old, naked and armed with a broom according to the Kunimasa version -- dressed, broomless, and not obviously winning her struggle with Tokunaga

Masakichi -- identified as a "young man" -- possibly the one who insulted Tokunaga in his capacity as hustler and enforcer

Aruji Shigeju -- "Propritor" Shigeju, called Shigejuro in the story

Shinzo [Shinzao] Okayo -- "Newly made" Okayo, whose career as a courtesan entertainer appears to have ended practically before it began

The purple noren at the entrance reads "Sugitoya" from the outside.

Story translation

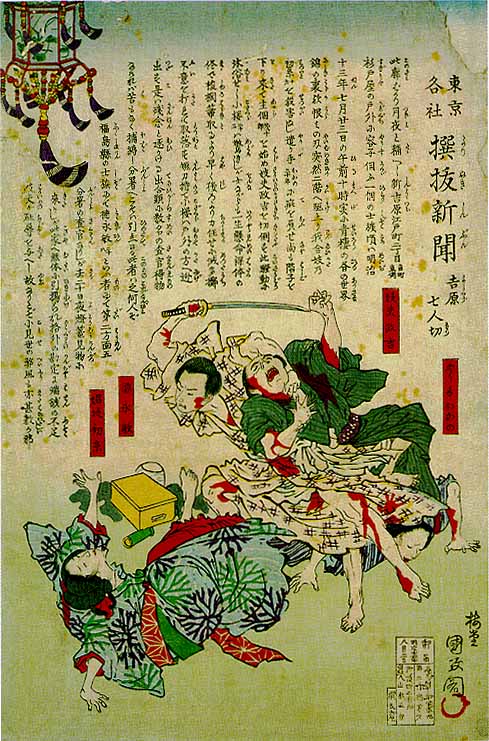

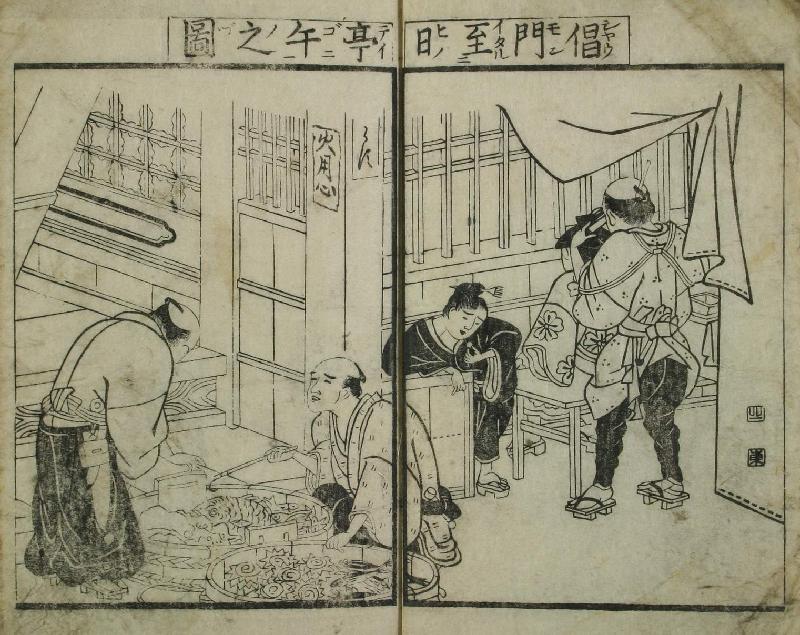

Picture of seven-person slashing at Sugitoya

rental cushion house, Edomachi 2-chome, Shin Yoshiwara

On the night of the 20th day of the 7th month of the 13th year of Meiji [20 July 1880] a young man called Tokunaga Bin, a shizoku of Fukushima prefecture, came for lantern viewing / but at a rental cushion [house] [= brothel] called Sugitoya on the south side of Edomachi 2-chome in Shin Yoshiwara was pulled up [into the house] incorporally [= against his will] / and then a young man [= tout] heaped humiliation [on him] over a deficiency of a paltry amount in a calculation [of charges] beyond the usual / and so at ten before noon of the coming 23rd day of the 7th month -- [as in] Behind the brocade: as things are during the day in the green towers [= brothels] -- [his] sword of malice aiming at the second floor, [he] ran up, and the winds of impurity [= impermanence] murdered the courtesan, Hatsuito, his accompanist, age 16 in years passed, and [her] manager, Okano, age 30 in years passed, bore wounds / then [he] descended the stairs and cut down first the proprietor Shigejuro and [then] the young man Masakichi / and in this commotion the courtesan called Kozakura, who had been bathing, was greatly startled / and though a woman, with all-out effort -- and as [she was] when [she] arose from the bath [= naked] -- [she fought him], and taken by surprise he dropped his short sword, and taking the thing Kozakura ran to the front and appealed to [some] police and they hauled [him] to the precinct.

[Translated by William Wetherall]

Terminology

shizoku

Shizoku (士族) was one of four legal statuses created between 1869 and 1892 out of earlier social castes. The seven or eight castes that formally defined people under Tokugawa laws were regrouped into four castes -- koshitsu (imperial family), kazoku (titled nobility), shizoku (ex-samurai), and heimin (commoners).

Most shizoku were of samurai descent. When domains became prefectures, samurai lost their status as retainers and had to survive on their own, without the entitlements they had received for their service to a domain. In return for losing what for most samurai had been a birthright source of livelihood, such samurai, when disenfranchised, were made shizoku -- a new social status for such former samurai -- and given a small stipend to help set up a business or otherwise start a new life.

Most shizoku were from the more influential military families (buke) that had immediately served a daimyo or the court. Lower-ranking samurai became commoners. Some, like Fuchichi Gen'ichiro, had no trouble forging a career and acquiring the wealth that came with economic success. Others, like Fujiwara Naoyoshi in Shooting birds at rest, had difficulty adapting to the new conditions and ended up poor and desperate.

Tokunaga Bin appears to have made the transition without great difficulty, in that he was employed as a policeman when he attempted to repair his damaged pride with his sword.

lantern viewing

Lantern viewing (灯籠見物 tōrō kenbutsu) generally alludes to taking in the nightscape of an entertainment quarter where lanterns have been set out.

The lanterns may be those commonly placed along the streets of an entertainment area merely to illuminate the streets and attract attention to the establishments along them. Or they may be related to a festival, especially those that would be set out on the last days of bon, possibly afloat on a stream or other body of water, to guide the spirits of the dead back to their world.

Bon is the period during which the spirits of the dead return for a few days to visit. On the lunar calendar, it was typically observed from the roughtly the 13th through the 17 days of a month -- i.e., two days before and after the 15th, the day of the main festival. Small fires would be lit in front of homes a few days before the full moon, and lanterns would be set out a few days after, to guide back and then send off the visiting spirits.

rental cushion house

A cushion renter (貸座蒲 kashizabu) was an establishment that rented cushions (座蒲団 zabuton) to, usually, male guests and their pleasure women -- in other words, a brothel. Higherclass brothels were generally called "sitting room [parlour] renters" (貸座敷 kashizashiki). Sitting cushions are more commonly called "zabuton" (座布団, 座蒲団). The shorter term "zabu" may also designate the round cusions used for zazen meditation.

Shin Yoshiwara

Yoshiwara Yukaku (吉原遊郭 Yoshiwara Yukwaku) -- literally "Yoshiwara pleasure quarters) -- was originally located near present-day Nihonbashi. Plans to relocate the district, then close to Edo castle, were implemented after the Meireki fire of 1657 destroyed much of Edo, including Yoshiwara.

A new Yoshiwara was constructed on reclaimed land near present-day Asakusa. Lots were allocated along several streets that led off either side of a main avenue approached through a single entrance gate. The blocks within the entrance was surrounded by moats that drained water from land while serving as a barrier.

The new district was called Shin (new) Yoshiwara, and the old district was referred to as Moto (former) Yoshiwara. In time the "new" could be dropped with no loss of understanding, but two centuries later, as in the story on this print, the district was still formally referred to a Shin Yoshiwara.

young man

A "young man" (妓夫 wakai mono, gifu, gyou) was a man -- of any age -- employed to do various jobs in a brothel, from hustling trade, billing and collecting, enforcing house rules, and taking care of baths, sitting rooms, and other facilities. In larger establishments, male servants would be assigned specific tasks, but in smaller places a few men would do everything, as directed by the propritor, the manager, or possibly a courtesan.

Such male employees were sometimes called "cattle boys" (牛太郎 giu tarau) meaning "entertainer work boys" (妓夫太郎 gifu tarau) -- both of which terms were read "gyou tarou".

"fu" (夫) is a general suffix for someone who does work related to affixed topic. For example, a man who pulled a jinrikisha was a 車夫 (shafu, kurumahiki), and a laborder or coolie was a 工夫 (koufu).

Behind the brocade:

as things are during the day

in the green towers

This is an allusion to the title and subtitle of a late 18th century work of fiction by Santo Kyoden. This and other works by Kyoden were censored in a show of force by authorities attempting to impose controls on printed matter featuring places of entertainment, including kabuki theaters and tea houses.

See Behind the brocade at the end of this article for a fuller description of this work and an image of the first page of its preface.

green tower

A green tower (青楼 seirau > seirō) was a storied building, house, palace -- a "tower" (楼) lacquered bluish-green (青) lacquer -- full of beautiful women. A Chinese term for brothel, this term was used during the Edo period to refer to a pleasure house, particularly one that was licensed.

sword of malice

A "sword of malice" (恨みの刃 urami no yaiba) was a sword drawn in resentment of an act or situation one intends to avenge with the sword. As harboring hate or bearing a grudge are regarded as self-defeating, whoever takes up a sword in revenge is also bound to harm oneself.

There is play on "ura" in the transition from the "nishikie no ura" to "urami no yaiba" -- linked by "ka" (written 歟 in the Kunimasa version), which renders the expression it follows as probable rather than definite.

winds of impurity

winds of impurity (無浄 mujiyau, mujou) alludes to the more common expression, winds of impermanence (無常 mujiyau, mujou) -- meaning that "impermance takes away the lives of people, as the wind scatters blossoms" (Kojien). "Impermanence" is the fundamental condition of existence, and all material and spiritual entities are subject to its forces of mutability.

The expression, very common in Japanese literature, very roughly corresponds to the Grim Reaper, who can come any time, and will come sooner later, to claim any and every life.

Japanese-Portuguese dictionary

Kojien (5th edition) attributes the expression "to be enticed by the winds of impermanence" (ムジャウノカゼニサソワルル mujiyau no kaze ni sasowaruru) to the "Nippo jisho" (日葡辞書 / Vocabvlario da Lingoa de Iapam), a Japanese-Portuguese dictionary compiled by the Society of Jesus and published by Nagasaki Gakurin in 1603. I have not seen this dictionary, but I presume that the katakana expression in Kojien is a transliteration of one of the 32,293 entries written in contemporary Portuguse romanization.

2007 film "Mujo No Kaze"

Dean Yamada, a professor of film at Biola University in La Mirada, California, took ten of his students to Tokyo in 2007 to film a short movie called "Mujo No Kaze" (The Wind of Impermanency / 無常の風). The film won the grand prize for best short film at the Rhode Island International Film Festival. It's website gives the following synopsis.

After a Japanese exchange student is murdered while studying in the US, his best friend in Tokyo is thrown into a world of depression in which a series of hallucinations lead him to a divine encounter in the countryside. Mujo No Kaze is a short film about finding hope in the midst of depression, suicide, and the futility of life.

courtesan

A courtesan entertainer (昌妓 = 娼妓 shiyaugi > shougi > shōgi) was a licensed prostitute whose status varied according to the class of the teahouse that trained or acquired her, and in either case kept her in its debt until she or a patron paid it off.

The key word here is "courtesan" (娼 shiyau, shou), a Chinese term for "prostitute". Used by itself in Japanese, the character is generally read "utaime" (歌女) meaning "singing girl" (歌女 kajo), or "asobime" (遊女) meaning "pleasure girl" (遊女 iujiyo, yuujo).

Most commonly, though, "courtesan" (娼 shiyau, shou) is found in compounds like "courtesan entertainer" (娼妓 shougi), "courtesan woman" (娼婦 shoufu), "street courtesan" (街娼 gaishou), "courtesan girl" (娼女 shoujo, utaime), "courtesan house" (娼家 shouka), and "courtesan tower" (娼楼 shourou).

While all of these terms can be used to disparage a woman or girl as a prostitute, harlot, whore, strumpet, tart, slut, hooker, woman for hire and the like -- some, particularly "courtesan entertainer" (娼妓 shougi), are often used as a job description -- as one might use expressions like "sex worker" or "sex entertainer" today -- without moral judgment.

official coutesan

An "official courtesan" (公娼 koushou) was a publicly, i.e., legally recognized "courtesan entertainer" (娼妓 shougi) -- and the latter term is often used to mean the former -- i.e., a licensed prostitute.

Of interest here is Marleigh Grayer Ryan's qualification of "prostitute" after using the word to describe the future wife of the novelist Tsuboichi Shōyō in The Development of Realism in the Fiction of Tsubouchi Shōyō, Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1975, pages 26-27, underscoring mine).

|

One liaison formed by Tsubouchi in the quarter where he and his friends spent so much of their time proved of great significance to his life and perhaps explains more than anything else how it is he was able to write so well about women. In 1884 he became acquainted with a prostitute named Katō Sen, a young woman six years his junior, [Note 4] and, after continuing to patronize her for three years, arranged for her to move to his house in July of 1886. They were married in October of that year. The term "prostitute" is used advisedly, for Sen was not a geisha nor did she belong to the higher ranks of the system by which the geisha, courtesans, and prostitutes were arranged in the licensed quarters. The house to which she was bound by contract was the second largest in the Nezu district, a new licensed quarter in downtown tokyo near the university [of Tokyo], established in 1870. Although reputedly beautiful, Sen was not one of the more valued women in the house, being given a third or fourth rank. She had a three-year contract at the house for which she was paid 600 yen. |

Ryan's commentary on the "little" she was able to discover about Sen and her influence on Tsubouchi's life and career continues for another two pages of text (pages 27-29), in addition to Note 4 (pages 26-27), which itself amounts to a page of text. The commentary constitutes a rather interesting look at the complications of marriage between "prostitutes" and men from "respectable" families.

For more about Tsubouchi's life and his views of the novel as art, see the commentary in TNS-1054 Confessions of evil.

accompanist

An accompanist (合妓 = 相方 aikata) was a woman assigned to accompany and entertain a guest.

Forthcoming.

manager

A manager (遣り手 yarite) was a veteran courtesan who oversaw the younger women, in addition to receiving guests, assigning them women, and overseeing services. They might themselves still entertain a patron or other favored guests but generally they were retired as courtesans and put their experience to use in running the house.

proprietor

The proprietor (主個 aruji) was the nominal owner of the house, who was on hand, to make sure the manager and the young men did their work, but also to attend to the more general business and legal aspects of the operation.

Transcription and romanization

The text in the story cartouche consists of 21 lines. I transcribed and romanized these lines as written then amended them to show how the the text was probably intended to be read. The amendments are marked as follows.

Transcription

The transcribed text shows (1) hentaigana in okurigana and furigana in present-day standard hiragana while preserving the original orthography, (2) furigana in (parenthesis), (3) presumed unwritten markers in [brackets], and (4) standard forms of unconventional kanji and kana in "sic" [brackets].

The writing also suggests haste, for above the 彳 of 行 in おかの行年 (Okano kaunen) is what appears to be a superfluous brush stroke -- as though the calligraphy (or carver) wrote the first stroke of 彳, then started over -- to adjust the spacing in the line, if not because of a distraction.

The style and presentation suggests the hand of a copiest rather than a writer -- of someone who set out to merely adapt a newspaper account to the space allowed for the story cartouche, rather than create an original story. In many other ways, too, the text is stiff and compact in the manner of a news report -- compared with the more readable and more interesting narrative in the news nishikie version (see below).

Romanization

The romanized text represents the orthography of the received text, plus the amendments made in the transcription. Kanji without furigana have also been romanized according to contemporary orthography. While は (ha), を (wo), and へ (he) are usually romanized wa, o, e when used as post-positions, but here they are shown as presented. Hyphens at ends of lines show breaks in words that continue on next line. Slashes show the junctures between phrase groups that have been marked in the translation.

Transcription

新吉原江戸町 / 二丁目貸座蒲 福島県之士族にて徳永敏とゆふ Romanization

Shinyoshiwara Yedomachi / 2-chaume kashizabu Fukushima-ken no shizoku nite Tokunaga Bin to yufu |

Baido Kunimasa's shichiningiriKunimasa's picture shows Yarite Okano on the floor behind Wakaimono Masakichi getting roughed up by Tokunaga Bin, who is about to dispatch Shogi Hatsuito. The picture is at odds with the action described in the story -- which, apart from a different narrative structure, and a few details, is like that on the Chikanobu triptych. Different narrative structureThe stories on the Chikanobu and Kunimasa prints are told very differently. The Chikanobu print presents the first visit, second visit, and arrest, while the Kunimasa print gives an account of the second visit and the arrest, then reveals the first visit through the investigation. Both accounts are chronological, but their narrative voices -- their points of view -- differ. The Chikanobu account is closer to a dessed down, straight news report. The Kunimasa account is more like a story that a gesaku writer or oral narrator might tell, in that it is is recited in a more entertaining manner and is framed in commentary. The Chikanobu triptych narrates the story from the point of view of an omniscient observer who has investigated the incident and has all the facts. The narrative starts from the culprit's first visit and ends with the culprit's arrest. The action unfolds in chronological order, and some details -- such as the identity of the culprit and elements of motivation -- would not have been known to a casual observer until there had been an arrest an investigation. The Kunimasa print also tells the story in chronological order, but from the second visit, and from the viewpoint of an uninitiated witness, who has never seen the culprit before and does now know what happened before the incident. Hence details about the culprit's identity, and the culprit's earlier visit to Sugitoya, are not revealed until after the arrest and investigation. And the police, to their surprise, discover that Tokunaga is one of their own. More information and interpretationThe story on the Kunimasa print conveys some information not revealed in its Chikanobu counterpart. Tokunaga Bin was 28 years old. Moreover, he was a patrolman from the 2nd-district 5th-precinct. Kozakura was 23 years old. Sugitoya was on the "side side of Sumicho" (角町東側 Sumicho higashiagawa) of 2-chome in Edomachi. It was a "small establishment" (小見世 komise), or a third-tier house, most likely lower class and cheaper than a big house (oomise) or a medium house (nakamise). The Kunimasa narrative contains an interesting variation of reading of 戸外. It begins with a "shizoku" checking out the situation at the 戸外 (kadoguchi) or "corner entrance" of Sugitoya -- meaning he arrives at the entrance of the establishment from the outside and sizes up the place as he goes in. Whereas Kozakura flees to the 戸外 (omote) or "front" of the place -- meaning she goes outside. The narrator does not pretend to know the name or other particulars about the man. At this point he is just a shizoku. This is conceivable because something about the man's bearing -- the way he dressed and walked -- suggested he had been a samurai. Naked and broomedThe Kunimasa and Chikanobu prints agree that Kozakura had been taking a bath when she heard the commotion. But the Kunimasa version is more specific about her state of dress, and how she was armed, when she took Tokunaga by surprise. Still naked (裸体の儘 hadaka no mama), she took a hemp-palm broom (棕櫚箒 shiyuro hauki > shuro hōki > shurobōki) and quickly beat the assailant from the back with all her might -- then, grabbing the sword he had dropped when taken by surprise, she escaped out the front. There she had no trouble getting the attention of some police, who converged on the assailant, easily captured their prey, and hauled him in. The broom was of the soft kind still used by some people today to sweep tatami. There would have been several out and around, during the day, while cleaning the sitting rooms. Partly blames old practicesThe story on the Kunimasa print closes with a remark to this effect:

Bad practices (弊風 heifuu) are the conventional ways many tea houses squeezed guests for all the money they could be conned or intimidated to pay. All establishments had fees for services, to which were added surcharges -- some standard, others based entirely on how much the house thought it could sucker out of a guest it figured would not be coming back. |

Sugitoya seven-person slashing incident

Yoshiwara was the setting for a number slashing rampages, mostly by angry young men full of sake and hurt pride, though now and then a woman wielded a knife to avenge the wrongs done her.

What, though, really happened at Sugitoya? Who was Tokunaga, and who were his victims, and what became of them?

Sugitoya incident

Forthcoming.

Wakasoro incident

Akimoto Hajime gives a brief account of a slashing rampage a decade after the Sugitoya incident -- which upped its count of seven victims by one (Akimoto 2006:207).

In 1890, Kanei Kiyokichi, a 25-year-old electrical company employee, found himself refused service in Yoshiwara because he had run up a bill of 10 yen. Moreover, he had just lost his job.

Blaming his problems on Wakasaro, Kanei boarded the place with a broad-bladed knife used for cutting large fish and a smaller knife, he killed one of the young men (岐夫太郎 = 妓牛太郎 gyuu tarou) out-right and seriously cut up seven others, including the proprietor and some courtesans, then survived an attempt to kill himself.

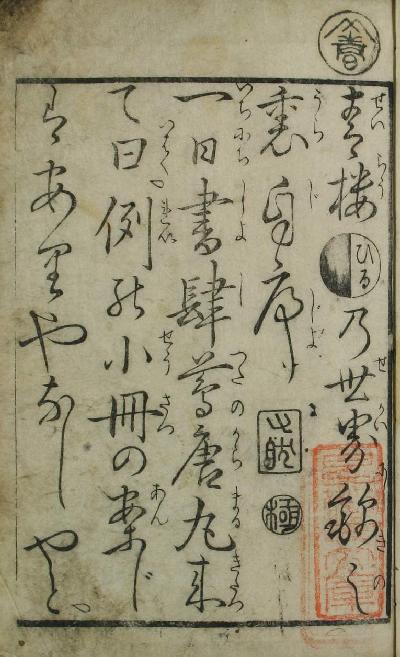

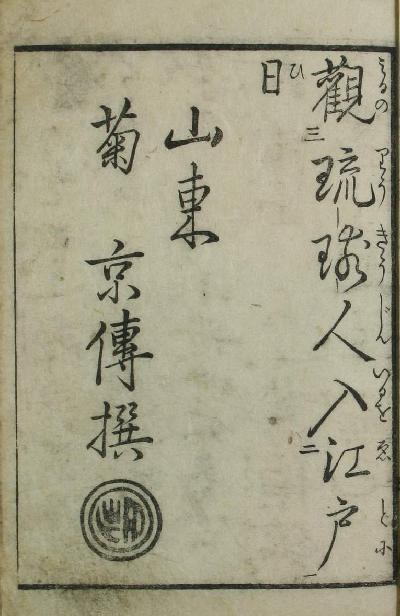

Behind the brocadeTo the right are images of the first and last pages of the 5-page preface to Nishiki no ura [Behind the brocade], an 80-page fictional work written and illustrated by Santō Kyōden (山東京傳 1761-1816). This edition, apparently the first, published in the spring of 1791, has 40 leaves folded and bound in a cover. The title strip on the cover (not shown) reads 錦乃裏 (Nishiki no ura). The preface title transcribes, transliterates, and translates as follows.

Note that while the title strip has 錦乃裏 the preface has 錦之裏. Waseda University Library's Japanese & Chinese Classics (古典籍総合データベース) [Old texts general database] gives the full title as 青楼昼之世界錦之裏 -- which both characters for "no" are 之 rather than 乃. Only 之 is recognized in the database search box. The seal in the margin above the first line reads "Santo" (山東). The word for "day" (ひる hiru) is shown on the sunny side of the day/night icon. Note that the database title renders this with the graph 昼 -- which is generally read ひる (hiru). There are two seals after the title of the preface. Mizuno says only that these two seals do not appear on later editions (Mizuno 1958:418, note 1). I have not yet been able to read the first, but the second is clearly a "kiwamein" (極印) -- a seal which, in principle, means that the work was vetted and approved by an official before publication. Kiwamein, which had just been introduced as part of the Kansei (Kwansei) reforms, were sporadically used until "aratamein" (改印) were introduced early in the 19th century. Some year-month "approval" seals appeared in the first decades of the 19th century, then during the Tenpo (天保) reforms -- from 1842, half a century after the Kansei reforms -- authorities again cracked down on printed matter and punished a number of publishers and writers for alleged violations of restrictions on content. Kansei reformsThe image to the right shows the last page of the 4-page postscript to the original edition of Nishiki no ura. The lines on the left show the date -- "Time [= season] Kansei [Kwansei] third-year metal-pig spring first-month" (時寛政三年辛亥 / 春正月) -- roughly February, March, and April of 1791. In 1911, two sexagenary cycles later, the same "metal-pig" (辛亥 kanoto-i, shin-gai) year inspired the "Shinhai Revolution" (辛亥革命 Xinhai Geming), which led to the founding of the Republic of China. The next line reads "Kyoden jibatsu" (京傳自跋) meaning that Kyoden himself wrote the afterword. The two seals read "Kyoden" and "Santo". Later the same year, Kyoden was arrested for this and other works, when the government -- during the Kansei reforms -- imposed stricter controls on the content of printed matter, including fictional stories and woodblock pictures. The censorship was part of measures undertaken by Matsudara Sadanobu (松平定信 (1759-1829) during his term from 1787 to 1793 as chief elder councilor (老中首座 roju shuza) of the shogunate under Tokugawa Ienari. Kyoden -- as Santo often referred to himself -- was sentenced to fifty days of confinement in manacles (手錠 tejo). Punishment by manacling was imposed on commoners for various misdemeanors. The length of the sentence could be 30, 50, or 100 days. The manacles were checked every other day in cases of 100-day sentences, and every fifth day for shorter sentences. A number of publishers, writers, and drawers received such sentences during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. IllustrationsThere are two illustrations in the original edition of Nishikie no ura. The first -- labelled "frontispiece" (口絵 kuchie) and signed "Santo" (山東) -- shows what appears to be a man buying fish from a vendor, and a man dressing the hair of a woman (see also Mizuno 1958:419). The Chinese caption across the top -- punctuated to facilitate its reading in Japanese -- transcribes, transliterates, and translates as follows.

In other words, Nishiki no ura is exactly what it's title promises -- a glimpse of life on an ordinary day in the not so extraordinary world of ordinary courtesan houses. Kyoden's wife OkikuThe attributions at the end of the preface show -- at the head of last line, to the left of Santo (山東) and above Kyoden (京傳) -- the name Kiku (菊). Mizuno says this refers to Kikuzono, who Kyoden married in the 2nd month of the previous year (Mizuno 1958:418). Okiku, as she is usually called, was the first of two women Kyoden married, both of whom were courtesans. Her name on the preface implies that Nishiki no ura reflects not only his observations, but also her insights into Yoshiwara's daytime world. Yoshiwara was also known as a "nightless citadel" (不夜城 fuyajyou) -- a Han Chinese term for a certain fortified city where the sun came out at night as well. The term was later used to describe a lantern-lit entertainment street as bright after dark as during the day. Kornicki 1977, which appears to include a full translation of Nishiki no ura, translates the fuller title as "A Brothel in the Light of Day: The Other Side of the Brocade". Miller 1988 refers to the work as "The World of a Brothel During the Day: The Other Side of the Brocade". |

Sources

The 1880 incident is often described in books and mooks on criminal history. Two such works proved useful, even as sources of confusion -- the usual result of efforts to resolve conflicts in received stories.

There are numerous versions and studies of Santo Kyoden's stories in Japanese, and a few in English. Some of these, too, were consulted.

Japanese sources

Akimoto 2006

Akimoto Kazu

Akasen jiken shi:

Yoshiwara "Sugitoya" junsa shichiningiri jiken /

Yoshiwara "Wakasaruro" hachiningiri jiken

[Red light incident history:

Yoshiwara "Sugitoya" policeman seven-person slashing incident /

Yoshiwara "Wakasaro" eight-person slashing incident]

Pages 206-207 in Bessatsu Rekishi dokuhon No. 45

Rekishi no naka no yujo: Hisabetsu min (Nazo to shinso)

[Pleasure girls in history: Discriminated people (Riddles and truths)]

<The Mystery of Yujo & Discriminated People>

Volume 31, Nomber 19 of Rekishi dokuhon

Tokyo] Shin Jinbutsu Orai Sha, 2006 (2007 reprint)

300 pages, magazine

Mizuno 1958

The original edition of Nishikie no ura is fully reproduced and annotated in Mizuno Minoru's anthology of kibyoshi and sharebon (NKBT No. 59, Mizuno 1958:417-440).

Mizuno Minori (vetting and annotations)

Kibyoshi / Sharebon shu

[Anthology of kibyoshi and sharebon]

Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1969

Nihon Koten Bungaku Taikei No. 59

[Survey of classical literature of Japan]

Yamashita 1988

Yamashita Tsuneo

Meiji Tokyo hanzai koyomi: Meiji gannen - Meiji 23-nen

[Meiji Tokyo crime almanac: 1868-1890]

Tokyo: Tokyo Hokei Gakuin, 1988

258 pages, hardcover

This book looks at one major crime for each of the first 23 years of the Meiji period.

1871, for example, saw the poisoning of Kobayashi Kinpei by his mistress Harada Kinu (c1843-1872), who had taken up with the actor Arashi Rikaku, then known as Inoue Kikugoro, later as Ichikawa Gonjuro. The following year, Harada was executed and Rikaku was sentenced to two years in prison. Their sentences were handed down on Meiji 5-2-20 (1872-3-28) reported three days later in the third issue of Tokyo's first daily newspaper, Tokyo nichinichi shinbun (Tokyo daily news). See Okinu and Rikaku for further details about this crime.

Waseda University Library

Waseda University Library's Japanese & Chinese Classics (古典籍総合データベース) [Old texts general database] has high resolution scans of all pages of two editions of Nishikie no ura. One is the original edition, from which I cropped the first page of the preface shown above. High quality images of numerous early manuscripts and woodblock printed texts can be viewed and downloaded from this WUL's on-line archive.

English sources

The following articles appear to be worth further pursuit for readers of English interested in Edo period stories -- though I have not seen them except in first-page JSTOR teasers.

Devitt 1979

Jane Devitt

Santo Kyoden and The Yomihon

Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies

Volume 39, Number 2 (December 1979)

Pages 253-274

Kornicki 1977

Peter F. Kornicki

Nishiki no Ura: An Instance of Censorship and the Structure of a Sharebon

Monumenta Nipponica

Volume 32, Number 2 (Summer 1977)

Pages 153-188

Miller 1988

J. Scott Miller

The Hybrid Narrative of Kyoden's Sharebon

Monumenta Nipponica

Volume 43, Number 2 (Summer 1988)

Pages 133-152