|

Nichinichi shinbun In 1871, 4 vessels returning to Miyakojima (宮古島) and Yaeyama (八重山) from the Ryūkyū capital at Shuri (朱里), where they had brought annual tributes, were caught in a typhoon. Two were able to return, one drifted to the west coast of Taiwan, and the other wrecked offshore in Hachōwan (八瑤灣) off the east coast of the southern tip of Taiwan. Some 54 of in wricked during a typhoon, drifted to blown off course by a typhoon, and drifted, wrecked official Ryūkyū vessels returning to Shuri (朱里) from Miyakojima (宮古島) with officials and annual tribute were blown off course in a typhoon and wrecked off the coast of the southern tip of Taiwan, where they were 、台湾南部の琅●(王へんに喬)付近の八瑤湾に漂着。漂着した乗員は原住民のパイワン(排湾)族牡丹社に救助を求めたものの、逆に牡丹社にあった彼らの集落へ拉致され、逃げ出したところをパイワン族から敵対行為とみなされて54名が殺されました。生き残った12名は漢人の移民により救助され、宮古島へ送り返されています

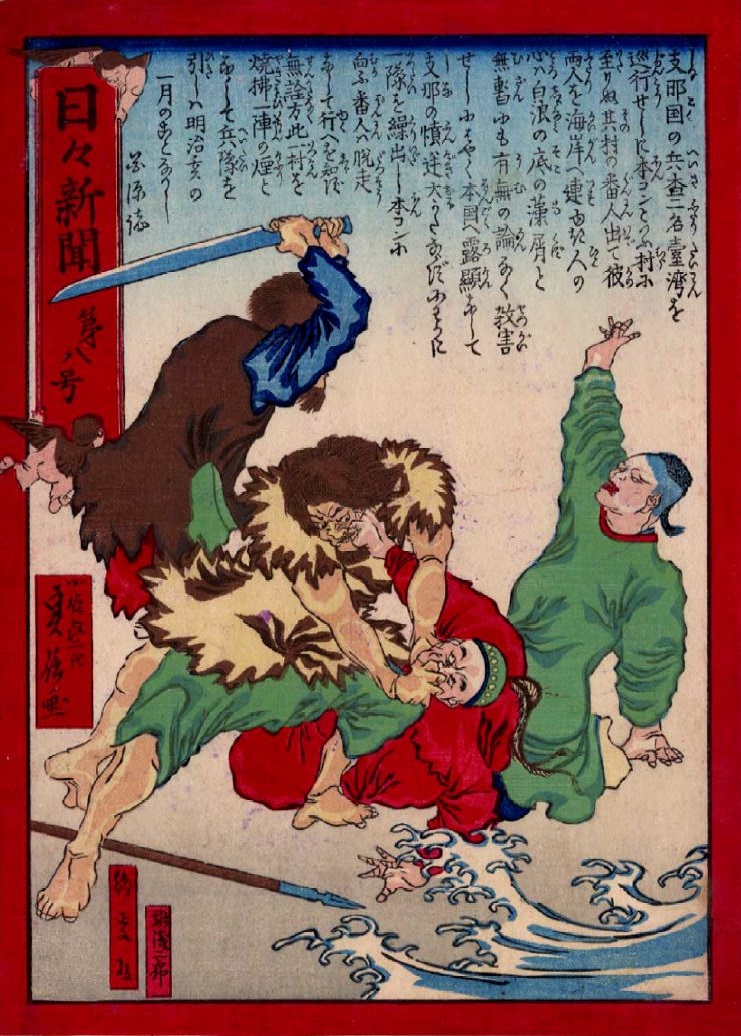

In January 1875, half a year after Japanese forces were sent to Taiwan to extract compensation for the killing of some shipwrecked Ryūkyū fishermen by some members of a native village in late 1871, some natives killed two Chinese military patrolmen who had come to their village. China retaliated by sending a military force to the village. The story was related in the following account by Kagen. |

Click on images Quality of printsNot seeing the prints in the same light with the naked eye makes comparison of their impressions and colors difficult. On the surface of their scans, the impression of the WRB copy (right) may be better, but the guard's face is obliterated by damage to the print and the colors may have faded. |

Nichinichi shinbun No. 8a

Nichinichi shinbun No. 8aScan of print in private collection Crop of screen capture from Tsuchiya Reiko, Tokyo: Bunsei Shoin, 2000 |

Nichinichi shinbun No. 8a

Nichinichi shinbun No. 8aScan of print in private collection used here with owner's permission ©2021 WRB All Rights Reserved |

Transcription of text and (furigana) on print支那国(しなこく)の兵査(へいさ)二名(ふたり)臺灣(たいわん)を |

Structural translationTwo soldier investigators of the country of China were patrolling in Taiwan |

||

Notes and comments

支那国 is marked to be read しなこく (Shina-koku) meaning "Shina (China) country" -- better known today as "Chūgoku" (中国) or "central country/kingdom". "China", as a word used by foreigners, probably derives from 秦 (WG Chin PY Qin SK Chin SJ Shin), an older name for China found in many early Japanese sources, in which the graph -- when referring to people of Chinese descent -- is sometimes read "Hata".

As a transcription of "China", "Shina" first appears in Chinese translations of Buddhist works that enter Japan directly from China or through Korea. It is widely used in Japan from the middle of the Edo (Tokugawa) period (1600-1868) to shortly after the Pacific War. It then fell out of grace due to complaints that it sounded derogatory to some people, hence its inclusion on many present-day "discriminatory word" lists. However, "Shina" continues to be used in historical contexts, and may be written in kana as しな or シナ to avoid 支那 -- one of several graphic transliterations of "China", including 脂那 (Shina), 至那 (Shina), 震旦 (Shinna), and 真丹 (Shinna).

二名 (nimei) read "futari" (二人) here.

臺灣 (Taiwan) is written with the fuller forms of the graphs, rather than with 台湾, the simplied forms that are standard today. Note, however, that the "koku" of both "Shinakoku" and "hongoku" is written with 国, today's simplier standard, rather than with 國, the fuller form. Some writers preferred fuller forms, some simpler forms, and not a few writers mixed forms, sometimes of the same graph.

Keep in mind that the kana and kanji in the story were carved backwards, by pasting the thin paper on which they were brushed face down on the block of wood used for the text. The choice of form -- fuller or simpler, block, semi-cursive, or cursive -- was the prerogative of the writer.

本コン (Honkon < Hoŋkoŋ < Hongkong) is katakana ホンコン in a 10 March 1875 Hōchi shinbun report (see "Sources" below), which describes the village as "north of . This probably a representation of the village of Hongkang (楓港 PY Fenggang WG Fengkang SJ Fūkō also "Hong Kang").

Hongkang is roughly 10 kilometers south of Pang-soa (枋山 PY Fangshan SJ Bōzan) on the westcoast of the southermost tip of Taiwan, and a bit further north of Kaikō (海口 SJ Kaikō).

彼両人 (kano ryōnin) is marked to be read "kano futari", which generally would have been written 彼二人.

藻屑 or "mokuzu" means "scraps" (kuzu 屑) of seaweed (mo 藻). The word is commonly used as a metaphor for what one becomes after death, especially at sea, such as in the phrase "kaitei no mokuzu to naru" (海底の藻屑となる), which means "to become seaweed scraps on the sea bottom". The expression here prefers Japanese "umi no soko" (海の底) or "bottom of the sea" to Sino-Japanese "kaitei" (海底) or "sea bottom", and replaces "umi" with "shiranami" meaning "white waves" -- choppy, foamy, white-capped waves. The fates of people who die at sea in storms or naval battles are commonly described this way. In English, people who die at sea, or are cast overboard or buried at sea, are said to meet or be sent to a watery grave, or to become food for fish, or to go to Davy Jones's locker, which is on the bottom of the sea.

Note that "hito no kokoro wa / shiranami no soko no "

無暫 (muzan) is usually written 無慚, 無慙, 無残, or 無惨, and means an offense committed without a sense of shame or remorse -- hence cruel or atrocious.

殺害 read "setsugai" here, usually "satsugai" today.

本国 read (hongoku), as it is today as a legal term referring to the "home country" or "country of nationality" of a company or individual in international private law.

露顯 (roken) is today written 露顕, and at times also 露見, and means the exposure, revelation, or bringing to light of something that might have been hidden or gone unnoticed.

憤逆, read "fungeki", is more commonly written 憤激 -- meaning a strong rage, anger, or irritation in response to, for example, a betrayal -- as being greeted with hostility when coming to deliberate.

無詮方 would read "musenkata" on its kanbun (Sinific) surface, but here it is marked to be read "senkata naku" (せんかたなく), a Japanese translation meaning "without method or means", in reference to something that cannot be helped or is inevitable, or by extension is intolerable or unbearable.

明治亥の一月 means "1st month of Meiji [year of the] boar" thus January of the 8th year of Meiji or 1875.

花源 (Kagen), aka as Kagendō (花源堂), who signed many Ōsaka news nishikie stories Sadanobu. These appear to have been the pennames of the Ōsaka publisher Maeda Kijirō (前田喜次郎 dates unknown).

Newspaper report

News nishikie stories were based on reports in newspapers. The above story is not sourced, but Tsuchiya Reiko's Bunsei Shoin CD-ROM collection (2000) includes the following transcription of an article attributed to the 10 March 1875 edition of Yūbin hōchi shinbun, Issue 610. The following representation is as copied and pasted from a txt file on the CD-ROM, except that I have broken the lines where the received text marks line breaks with slashes. I have not seen the original article and cannot confirm either the lineation or the accuracy of the graphic transcription. The second graph of the place name 琅☐ is described as 王編に喬)character of thethe accuracy of.

支那兵を台湾の番人が殺害 郵便報知新聞 第六百十号 明治八年三月十日 ○在台湾の報者一珍事を来訪せしか此報者ハ常に実事/を報告するに因り此度の報も亦虚ならさるべし去る/二月十二日頃とか琅〓(王に喬)の北方ホンコンと云一小部落/の近傍にて蕃人大勢不時に蜂起して支那兵を襲撃(ふいをうち)し/矢庭に指令官一名卒二百名を殺すの外傷者も猶多か/りしと此れ何等の趣意ありての事なるや未た其細情/を得されども必す支那より此報讐の処置を為すに至/るへし香港日々刊行Background

Taiwan is home to several ethnically distinct populations of people regarded as indigenous to the islands within historical times. People from the east coast of continental China began settling in the western parts of Taiwan facing the continent, in significant numbers, from around the 17th century, when Taiwan was wrestled from a few years of partial Dutch control, which had followed a period of partial Spanish control. The emergence of Chinese in Taiwan led to the overthrow of Dutch forces by Chinese forces led by the Ming loyalist Cheng Ch'eng-kung (鄭成功 Zhèng ChéngŌng aka 國姓爺 Koxinga 1624-1662), the son of Cheng Chi-long (鄭芝龍 Zheng Zhīlóng 1604-1661) from Ming China and a woman from the Tagawa family (田川氏) in Hirado in Japan. Cheng was motivated to control Taiwan as a base from which to restore the Ming dynasty after its overthrow by the Ching (Qing) dynasty. The Ching Dynasty didn't yield, however, Taiwan became part of its dominion.

Increasing humbers of settlers from the continent resulted in the the western coast and plains of Taiwan being domesticated by Chinese of various continental origins, while the native tribes were left to inhabit the rugged mountains along the east coast.

Taiwan's location off the massive continent made it a place where stormwrecked ships were likely to arrive, and survivors were not always welcomed. Toward the end of 1871 (Meiji 4), some 69 fisherman from the Miyako islands, which were part of the Ryūkyū islands, were shipwrecked off the coast of a Paiwan village on the southern tip of Taiwan. 3 were drowned, and among the 66 survivors, 54 were killed by Paiwan villages and 12 were rescued by Chinese. Japan took the position that the Miyako fishermen were its subjects, but China took the position that the Paiwan villagers were outside its jurisdiction.

Japan's Meiji government, formed in 1868, had started to nationalize local provinces into prefectures, and formally claim periphereal islands that had been loosely tethered to the some of the provinces -- including the Ryūkyū Kingdom, which paid tribute to China but had also been under the suzerainty of the Shimazu clan (島寿氏) of the Satsuma domain (Satsuma-han 薩摩藩), which became part of Kagoshima prefecture (Kagoshima-ken 鹿児島県). The founders of the Meiji government included several Satsuma samurai, who were instrumental in the Meiji government's move to secure the Ryūkyū islands as part of its sovereign dominion.

At the time of the 1871 incident in Taiwan, Satsuma was still a domain. And the Shimazu clan regarded the Ryuōs -- though still not part of Japan -- as a protectorate of the Satsuma domain. At the end of 1871 (Meiji 4-11-14, 1871-12-25), shortly after the Taiwan incident, Satsuma was incorporated into Kagoshima prefecture, and several months later in 1872 (Meiji 5-9-14, 1872-10-16), Japan formally declared Ryūkyō to be a domain, hence Ryūkyū-han (琉球藩). Taiwan was nominally part of Fukien (WG Fu-chien, PY Fujian, JP Fukken 福建) province.

This was the status of Taiwan and the Ryūkyū (Okinawa) islands as of 1874 when Japan -- or former Satsuma leaders in the name of Japan -- unable to get China to take responsibility for the actions of Taiwanese natives and pay compensation -- sent an expeditionary force to Taiwan to investigate and chastise those it regarded as reponsible for the killings. The expedition, which included 2 Americans in commanding positions, encountered resistance that ultimately resulted in the defeat and death of the responsible village chief, but also a defeat for the expeditionary forces, whose ranks were decimated by malaria. China, in response, paid an indemnity, and in 1875 attempted but failed to subdue hostile native tribes. In 1876, Japan and China would sign a conciliatory treaty establishing peaceful relations between the two countries -- until the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895, over Korea and not Taiwan, which resulted in China ceding Taiwan to Japan. Taiwan would remain part of Japan's sovereign dominion until 1945/1952, when surrendering in 1945 to the Allied Powers, including the Republic of China, and formally abandoning all claims and rights to Taiwan.

Taiwan was claimed by China but was not formally attached to Fujian province until later in 1875. Taiwan and the Pescadores were formally separated from Fujian province as Fujian Taiwan Province (台湾省) in 1885, and as such was ceded to Japan in 1895. The territory did not become "Taiwan provence" (台湾省) until it was nationalized by the Republic of China following its surrender to ROC several weeks after Japan surrendered to the Allied Powers in 1945. ROC did not formally establish the government of Taiwan Province until 1947, two years before ROC would establish its provisional (now permanent) capital in Taipei after being forced to retreat to the province by the establishment of the People's Republic of China on the continent in 1949.

Publishing particulars

Series: Nichinichi shinbun

Number: 8a

Story date: 1875-01

Story source: Possibly Yūbin hōchi shinbun, Number 610, 10 March 1875 (郵便報知新聞, 第六百十号, 明治八年三月十日)

Publisher: Watasei-han 綿政板, aka Wataya Kihee 綿屋喜兵衛, among other signatures of Maeda Kihee 前田喜兵衛

Drawer: Sadanobu II changed from Konobu 小信改二代貞信

Carver: Hori Asajirō 彫浅二郎

Writer: Kagen 花源, aka Kagendō 花源堂, among other signatures of Taisuidō Rishō 大水堂狸昇

Size: vertical chuban

Images: ©2000 Bunsei Shoin, ©2021 WRB, All Rights Reserved

Selected sources

Dozens of books and many more journal articles have been written in Japanese, Chinese, and English about the Taiwan Expedition. I have seen only a few materials, mostly secondary sources that make use of primary sources. Here are a few of the more available and readable accounts.

Government of Formosa 1911

臺灣總督府民生部

蕃務本署

明治四十四年十一月五日發行

明治四十四年十月廿五日印刷

Government of Formosa

Report on the Control of the Aborigines in Formosa

Taihoku, Formosa: Bureau of Aboriginal Affairs, 1911

iii (Contents, Tables, Maps), iv (Illustrations), 45 (text)

Ethnographical Map of Formosa

Between pages iv and 1

Map of Southern Formosa (Showing the District Occupied by the Aborigines)

Between pages 40-41

Eskildsen 2020

Robert Eskildsen

An Army as Good and Efficient

as Any in the World:

James Wasson and Japan's 1874 Expedition to Taiwan

Asian Cultural Studies

(Institute of Asian Cultural Studies, International Christian University)

Volume 36, 2020, pages 45-62

Barclay 2015

Paul D. Barclay, Lafayette College

The Relics of Modern Japan's First Foreign War in Colonial and Postcolonial Taiwan, 1874-2015

(Curator's statement)

Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review

(Institute of East Asian Studies, UC Berkeley · Research Institute of Korean Studies, Korea University)

E-Journal No. 17 (December 2015)

PDF file, pages 131-138, plus 23 photographs of related materials and monuments annotated by Barclay

Barclay 2018

Paul D. Barclay

Outcasts of Empire

(Japan's Rule on Taiwan's "Savage Border," 1874-1945)

Philip E. Lilienthal Imprint in Asian Studies

Berkeley: University of California Press, 2018

xvii, 328 pages, paperback

Including notes, glossary, and index, plus illustrations, maps, and tables

Eskildsen 2019

Robert Eskildsen

Transforming Empire in Japan and East Asia

(The Taiwan Expedition and the Birth of Japanese Imperialism)

Singapore: Springer Verlag, 2019

xix, 383 pages, hard cover