| Bibliography of news nishikie related publications | ||||

| Introduction | General | Stories | Drawings | Topics |

Exhibition publications

•

Machida 1986

•

Waseda 1987-1988

•

Toyohashi to Itabashi 1988-1989

•

Kinoshita and Yoshimi 1999

•

Printing Museum 2000

•

(The East 2000)

•

Hishikawa 2001

•

Newspark 2001-2002

•

Kagawa 2005

•

Itami 2006

•

Chiba 2008

Books and articles

•

Asahi 1979

•

Hara 1990

•

Ono 1972

•

Rekishi to tabi 1980

•

Schreiber 2004a

•

Schreiber 2004b

•

Takahashi 1986

•

Takahashi 1987

•

Takahashi 1992a

•

Toyo Daigaku 2003

•

Tsuchiya 1995

•

Umehara 1926

•

Umehara 1929

•

Wetherall and Schreiber 2006

Other media

•

Kitahara et al 1999-2001 CD-ROM

•

Tsuchiya 2000 CD-ROM

| Catalogs, books, and flyers related to exhibitions related to news nishikie |

1986 Machida Municipal Museum exhibitionMeiji newspapers in Hajima CollectionExhibition catalogMachida Shiritsu Hakubutsukan The exhibition, from 23 September through 19 October 1986, featured materials mostly from the collection of Hajima Tomoyuki (b1935), a well-known newspaper historian. The focus was on newspapers and kawawaban, not news nishikie. However, four small news nishikie are included in the eight color pages in the front. Black-and-white thumbs of about forty other news nishikie are paneled on five pages in a section on "nishikie newspapers" (nishikie newspapers). The catalog was low-budget, and many of its illustrations are barely legible. (WW) |

1987 Waseda University Library exhibitionNewspapers, nishikie, and handbills in Nishigaki BunkoExhibition catalogWaseda Daigaku Toshokan This is a catalog of items that appeared in an 1987-1988 exhibition at Waseda University Library. The items are from a collection called the Nishigaki Bunko, which is part of the library's Old and Rare Materials Collection, much of which is accesible on-line. As the exhibition title suggests, the catalog presents a broad range of visual media that includes advertising and popular culture in addition to news. A chapter on news nishikie features about forty color and black-and-white images of Tokyo nichinichi shinbun, Yubin hochi shinbun, and other prints. (WW) |

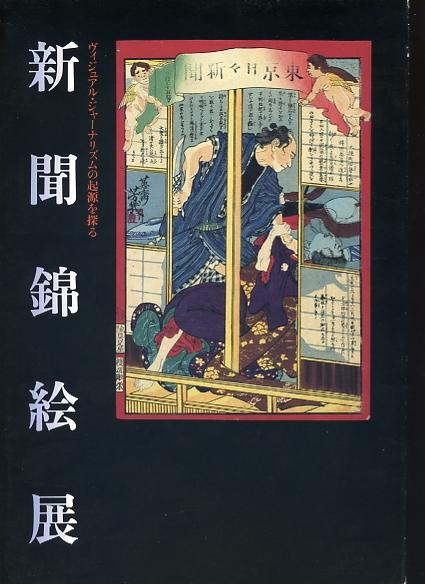

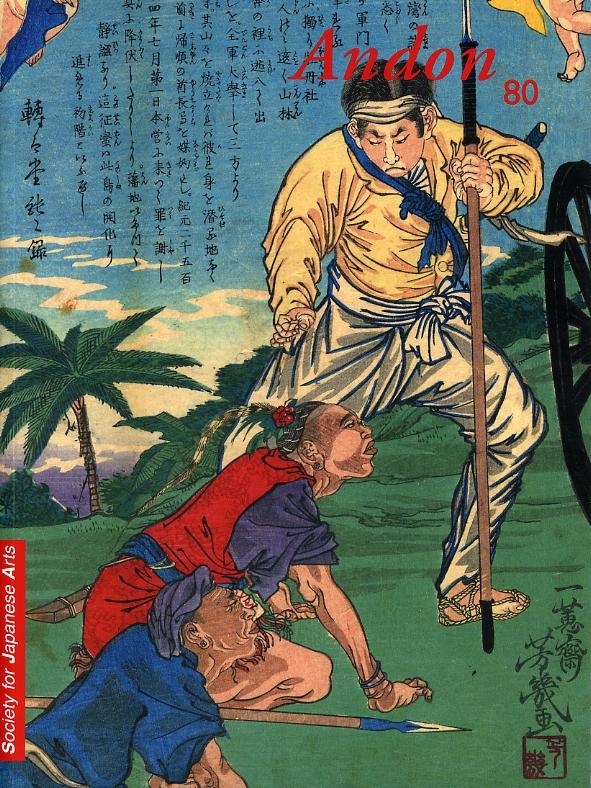

1988-1989 circulating exhibitionPrints from Takahashi, Hajima, and other collectionsExhibition catalogs and flyersThis exhibition, called Shinbun nishikie ten [News nishikie exhibition], was unusual in scope and influence in that it brought together news nishikie from a number of private collections and circulated them among four museums in Aichi, Hyogo, Fukui, and Tokyo prefectures in 1988 and 1989. 1988-04-23 to 05-22 1988-08-06 to 09-04 1988-09-10 to 10-10 1989-02-25 to 03-26 At least two editions of the exhibition catalog, with different titles and covers, were issued in 1988 and 1989. The following review is based on the 1989 Itabashi Art Museum edition, which does not include "ten" (exhibition) in its title but appears to have the same content its 1988 precursor. Jaanarizumu shi kenkyu kai (Kenkyu dojin) This is the best catalog of an exhibition dedicated to news nishikie. Many of nearly 183 prints, mostly Tokyo nichinichi shinbun (TNS) by Yoshiiku and Yubin hochi shinbun (YHS) by Yoshitoshi are shown in color. It features more YHS prints than any other catalog or book. The layout, text, and photography were done by Saruta Ryo and Kosokabe Hideyuki, and others in collaboration with Takahashi Katsuhiko, Hajima Tomoyuki, Asai Osamu, Yamana Sanzo, and Okada Zenji. (WW) |

1999 Tokyo University exhibitionKawaraban and news nishikie in Ono and other collectionsExhibition bookKinoshita Naoyuki and Yoshimi Shun'ya This publication is based on the first public exhibition of the Ono Hideo Collection, held in 1999 to mark the 50th year of Ono's founding of the Institute of Journalism and Communication Studies in 1949. The exhibition was jointly mounted at the University of Tokyo Museum by the museum and the Institute of Socio-Information and Communication Studies, as the original institute had been renamed. The book (more than just a catalog) is the best overall introduction to the emergence of news media in Japan with a focus on late Edo and early Meiji drawer newsprints (kawaraban) and nishikie. There is a wealth of material here, all generally well-presented and nicely illustrated in black-and-white and color. In the back are four one-page token English summaries that fail to do justice to the originals: Ono Hideo and His Collection" (Yoshimi Shunya) The University of Tokyo Digital Museum maintains an easily navigated web version (see Nyuusu no tanjo). And the Institute of Socio-Information and Communication Studies has published the entire Ono Collection as a CD-ROM under the same title (see ). (WW) |

2000 Printing Museum exhibitionThe printing culture of the Edo periodExhibition catalog印刷博物館 Printing Museum The structural translations in [square brackets] are mine. The translations in <angle brackets> are as provided in the catalog. The catalog represents a smaller special exhibition which ran in the Printing Museums's P&P Gallery from 7 October to 10 December 2000, hence a couple of weeks shorter than the main exhibit (see below). For a review of an English article which purports to have been based on this exhibition, see The East 2000 in this section. Tokugawa IeyasuTokugawa Ieyasu (徳川 家康 1542-1616) was the first shogun of the Tokugawa dynasty, which ruled during what is called either the Tokugawa period (politically) or the Edo period (geographically and culturally). Ieyasu was born the eldest son of Matsudaira Takechiyo, the lord of the Mikawa domain, now the eastern part of Aichi prefecture. Early in his life, Takechiyo came under the strong influence of the Imagawa clan of Suruga province, now the northeast part of Shizuoka prefecture. The Imagawa clan also dominated the Tōtōmi (Tootoumi > Too-tsu-oumi) domain, between Mikawa and Suruga, now the western part of Shizuoka prefecture. To keep a long and complicated story short, on his way becomeing Tokugawa Ieyasu, Takechiyo, from about the age of six, became a hostage of the Imagawa clan, which was deeply involved in the civil wars that raged throughout the country in the middle of the 16th century, took custody of the boy in return for coming to the defense of the Mikawa domain. By the time he had come of age and been allowed to return to Mikawa, Takechiyo had been thoroughly schooled in Suruga to fight for Mikawa as well as Imagawa causes that, in time, became his own -- from 1567 as Tokugawa Ieyasu. The exhibition catalogThe 2000 Edo printing culture catalog has nine articles and 132 items are shown in color plates. An index to the items includes monochrome pictures. The exhibited materials were intended to substantiate the claim that Ieyasu was a "moveable-type man". The catalog introduces "Fushimi-edition" publications printed with wood moveable type and "Suruga-edition" publications printed with copper moveable type. Both printing technologies were encouraged by Tokugawa Ieyasu, the first shogun of the Edo (Tokugawa) period, who is known to have had a strong interest in printing. Two introductory articles follow the table of contents. The other articles are grouped under three chapters.

2000 Printing Museum exhibitionThe Printing Museum, in Tokyo's Bunkyo ward, was founded in in 1987 as part of the research institute of the Toppan Printing Company, which was founded in 1900 by several technologists from the Printing Bureau of the Ministry of Finance. The museum celebrated both its opening to the public in 2000, and Toppan's centennial, with the following exhibition, which ran from 7 October to 28 December 2000. Name of exhibitionThe name of the exhibition included a number of titles and subtitles. Shown below are the Japanese titles, their romanization, my structural translation in [square backets], and the received English titles in <angle brackets>.

Awazu KiyoshiThe late Awazu Kiyoshi (1929-2009), a graphic designer, was the director of the Printing Museum at the time of the exhibition. The exhibition in his name is essentially inspired by his book, which was published with similar titles.

|

2000 Printing Museum exhibitionThe printing culture of the Edo periodReview articleThe Marriage of Pictures and Characters According to a statement at the end of this article, it was based on "the [Printing Museum's] inaugural exhibition." All five color images of historical printed matter in the article are credited to the museum. For a review of the museum catalog for the "Edo printing culture" exhibition, see Printing Museum 2000 in this section. Ends and oddsThe "visual culture" theme of the subtitle was common among a number of somewhat earlier and concurrent Tokyo exhibitions of late-Edo and early-Meiji woodblock print culture. This is mostly an attempt to impose present-day fashions of cultural discription and analysis on earlier times in order to arouse people's interest in history. The main title, however, is totally odd. As a general meteaphor, a marriage between "pictures" and "characters" does not make sense. A marriage of "pictures" with "text" or "stories" is more conceivable. The article, though, echoes and then resonates with the following linguistic claim (pages 57-58, and page 59, underscoring mine).

Imaginary social historySomeone -- the article does not say -- has "imagined" a lot. Apparently some or all commoners "might have" or "may have" seen "letters" or "characters" (apparently there is no difference) as "pictures" -- and at times been puzzled by nonsense which turned out to have meaning. By the end of the article, the "mights" and "mays" have vanished. The putative "lettering culture" is declared, by way of conclusion, to have stressed the "visual" -- which in turn inspired a "vigorous and carefree sprit" -- that in turn is boosted the social status of townspeople -- but where and how? In only the town of Edo? Or also in Osaka and other bustling centers of human activity? And how did anyone's status change merely by "seeing" meaning in "letters" or "characters"? Apparently "commoners" are "the masses" -- meaning who? Farmers? Craftsmen? Merchants? Lowly members of the samurai caste? Entertainers and others who might have been legally classified as eta or hinin, but might still have participated in "Edo printing culture"? Linguistic fallaciesWhat level of literacy is required to process any significant amount of text -- which, on most printed matter intended for wide commercial distribution, would consist of Chinese graphs called kanji and moraic script called kana? How far would any would be "reader" get with any such script without knowing the language -- without having learned the kanji and script in association with their linguistic attributes -- without, in other words, "hearing" the underlying language? The article utterly fails to address the socioeconomic realities of Edo printing culture. In fact, the people who produced the sort of graphic materials the article cites as examples of "visual culture" were themselves products of a society that was full of humor and mischief, which could be very politically incorrect in the eyes of authorities. The publishing marketThe vast majority of printed matter, including woodblock pictures that only latter developed into what became known as nishikie, were commodities -- produced at a cost and sold for a profit in order to make a living. The publishers -- and the drawers, writers, carvers, printers, and others they commissioned or hired -- knew their wares would attract a readership -- because they had a finger on the pulse of the denizens they sought to entertain if not also inform and educate with their products. Most of the genres of publications cited in the article appealed mainly to people who had acquired a taste for their peculiar features. They do not represent the mainstream printing culture, which was dominated by illustrated didactic texts and story books. Such reading matter was accessible only to those who were reasonably literate in vernacular writing, and who were motivated to read in a conventional way -- word by word, phrase by phrase. The limits of "typography"The article expresses surprise that during the Edo period people were more interested in "typography" than people today. How can this possibly be true -- since, contrary what the article implies, "typography" remained a very limited field until early in the Meiji period? If "printing culture" encompasses all methods of printing, then "Edo printing culture" is not characterized by "typography". Despite the availability of different kinds of "moveable type" (活字 katsuji), when it came to the mass reproduction of vernacular texts, most Edo-period publishers rejected moveable type for the flexibility of hand-carved woodblock texts. Woodblock-printed texts continued to dominate the publishing world in Japan until the importation and adaptation of metal type and related press technology during the first decade of the Meiji period. Some of earliest metal-type published newspapers and pamphlets continued to used woodblock technologies to print caligraphy on covers and illustrations embedded in the text. And some publishers of woodblock nishikie began using moveable type to produce the story text that accompanied a picture. The idea that people today are somehow more "oblivious to typography" is nonsense -- given the premium that publishers of any text in any medium today place on typographic design. And their efforts do not go unappreciated by their readers. News nishikieThe last illustration in the article is of a news nishikie identified as "Tokyo Nichinichi Shimbun, No. 933." For a closer look at this print and its story, see Man murders ex-wife (TNS-933) in the TNS gallery section of this website. The article under review makes the following statement about such prints (page 59).

Practically every phrase in this statement is incorrect. The newspaper called Tokyo nichinichi shinbun did not appear until early 1872. The series of nishikie prints based on stories taken from the newspaper did not debut until 1874, and was discontinued from the fall of 1875. The nishikie prints were not newspapers, besides which "shinbun" meant "news" -- and, today, still means "news" when used in the titles of newspapers. They were produced and sold in the same manner as other woodblock souvenir prints, and hence were not published in especially large numbers. The stories were in no way "Kabuki-like" or otherwise "exaggerated" but were written in an entertaining narrative style by seasoned writers of illustrated novels who had turned to journalism. All were based on actual newspaper reports. Some of the less inspired nishikie versions were phrased like the original reports, which were written as news reports. The "red ink" of the "frame" was a common element in many series of early Meiji prints. The color had nothing to do with the "bloodiness" of the incident depicted in TNS-933. Most such prints were not stories about murder or other acts of violence, yet all had the same red border -- as did some non-news-related series produced by the same publisher, and many prints general souvenir prints put out by other publishers. Striking red and purple were widely used during the early Meiji period as the new colors of progress. The borders of a rival series of news-related prints, based on stories from Yūbin hōchi shinbun, were a deep purple. In other words, the story about news nishikie, much less the picture of TNS-933, had no place in an artcile about "visual culture" in the Edo period. |

2001 Hishikawa Moronobu Memorial exhibitionSixty news nishikie reporting Meiji incidentsExhibition flyerHishikawa Moronobu Kinenkan This exhibition showed sixty Tokyo, Osaka, and other news nishikie in the collection of the Hishikawa Moronobu Memorial [hall, center, museum] in Kyonan-machi in Chiba prefecture. Moronobu (c1630-1694), an early Edo woodblock printmaker and painter, was one of the most important developers of ukiyoe and methods of mass printing color woodblock pictures. He was born and raised in the province of Awa, on the southern tip of present-day Chiba prefecture, hence the location of Hishikawa Moronobu Memorial in the town of Kyonan (Kyonan-machi) in the Awa district (Awa-gun) of Chiba. Moronobu may have been surprised, not only by the subject matter of news nishikie, but by their bold designs and loud colors. His pictures were compartively subdued, with softer lines and quieter hues, and did not portrary "incidents" of the kind that became popular from the late Edo period -- though a number of the prints and book illustratations attributed to him are erotic. |

2001 Japan Newspaper Museum exhibitionNews nishikie from Newspark and other collectionsExhibition bookNyuusupaaku (Nippon Shinbun Hakubustukan) (sponsors) This is a guide to an exhibition held at the Japan Newspaper Museum in Yokohama from 5 October 2001 through 14 January 2002. The exhibition was organized by Newspark (the museum's trendier name) and supervised by Yoshimi Shun'ya (see above) and Tsuchiya Reiko (see below). Though the exhibition is over, the museum has a few nishikie papers in its permanent display. And the guide continues to be sold at the museum shop, which is just outside the museum. The guide introduces its nishikie newspapers through the people produced them and inspired their stories. A 23-page appendix includes biographical information about Yoshiiku, Yoshitoshi, and other people in the nishikie newspaper world; an extensive bibliography; and a list of the museum's nishikie holdings with publication particulars. This is easily the highest quality publication of all those reviewed here. It is truly comprehensive, informative, and enjoyable -- on a par with the best museum catalogs -- and it comes at a bargain price. (WW) |

2005 Kagawa University Library exhibitionNews nishikie in Kanbara BunkoExhibition flyerDai-juikkai Kagawa Daigaku Fuzoku Toshokan Ippan Kokai Gyoji This exhibition showed fifty Tokyo, Osaka, and other news nishikie in the Kanbara Bunko (see elsewhere in this Bibliography), which is part of Kagawa University Library. The nishikie were captioned with titles from Tsuchiya 2000 (Bunsei Shoin CD-ROM). All are also viewable on-line, as are many other nishikie and other items in Kanbara Bunko. |

2006 Itami City Museum of Art exhibitionOsaka news nishikie from Osaka Castle MuseumExhibition catalogItami Shiritsu Bijutsukan (editor) Among the many exhibitions of news nishikie that have mounted at various museums in Japan, most have either focused on, or exclusively featured, Tokyo prints. This exhibition, held from 3 November through 17 December 2006, was exceptional in its focus on Osaka news nishikie. The catalog has black-and-white thumbnails of 209 prints, typically nine to a page. All but a few of the prints, at very beginning and end, were published in Osaka. Explanatory textBelow each of the images is an exhibition number followed by a very short phrase summarizing the nature of the story on the print. This information is in bold face. Below the number and summary line are three lines in plain face showing (1) the title of the series and the number of the print in the series, (2) the drawer of the picture, and (3) the orientation and size of the print, plus the name of the contributor. The vast majority of the Osaka prints were contributed by Osakajō Tenshukaku (Osaka Castle Museum), which is credited as a special collaborator. Some variations are shown -- but oddly. Because the prints are shown in order of their number within the name of their series, images of a few prints with "shinbun" suppressed from their title (bracketed as [新聞]) appear immediately after the images of the unsuppressed print. However, this ordering criteria means that identical prints with different titles are not shown together. The only accompanying texts are a short greeting by the head of the Itami City Museum of Art, and a two page introduction by Tsuchiya Reiko. At the end of the introduction is a list of four references: Tsuchiya 1995 (her book on Osaka news nishikie), Tsuchiya 2000 (Bunsei Shoin CD-ROM), Kinoshita and Yoshimi 1999 (Birth of News), and Newspark 2001 (Japan Newspaper Museum publication on news nishikie and the people who produced them). ONS-9001 diptychIncluded among the Osaka prints in this catalog is a full scan of the unusual horizontal chuhan diptych, the first sheet of which was used for the cover wraps. See Osaka theaters in Soga battle for a color image and details. |

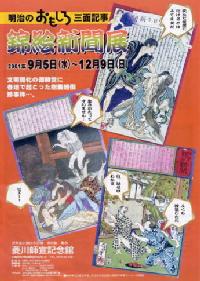

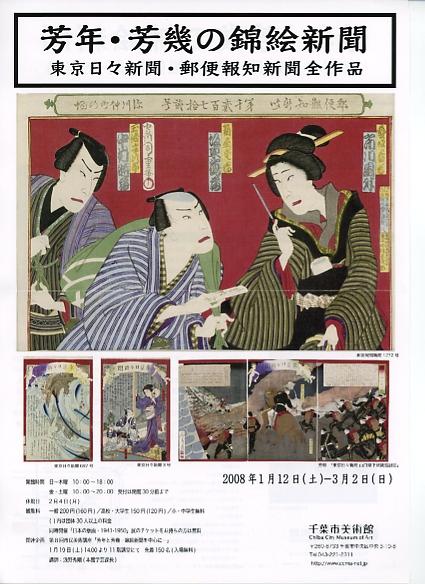

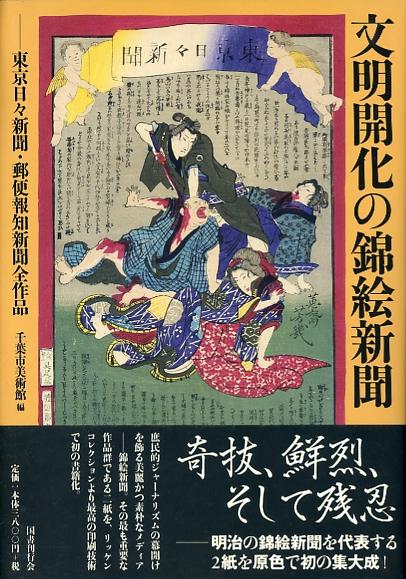

2008 Chiba City Museum of Art exhibition176 news nishikie from Rikken CollectionExhibition flyerYoshitoshi / Yoshiiku no nishikie shinbun: Exhibition bookChiba-shi Bijutsu Kan (Hen) The exhibition mounted the Tokyo nichinichi shinbun (TNS) and Yubun hochi shinbun (YHS) news nishikie in the Rikken Collection. Several prints not in this collection were borrowed from Waseda University, University of Tokyo, National Diet Library, and Chiba University. A few prints were shown as color copies, and one triptych was shown as a black-and-white copy. I went to the exhibition on 16 January 2008, a Wednesday. On that day, four prints (TNS-851o, YHS-507, YHS-1044, and YHS-9001 -- my nomenclature) were shown as color copies. One (TNS-9004) was shown as a black-and-white copy. Facsimilies of the source articles were shown for six prints. Ansei bridge triptychsTwo triptychs (TNS-9003o and TNS-9003r) received special attention, as they narrated a truly unusual story. The original print shows a fight between police and ruffians on Ansei bridge in Tokyo (TNS-9003o). The same or another publisher later replaced the text in the story cartouche which described the action as a skirmish between rebel and government forces at a bridge by the same name in Kumamoto (TNS-9003r). The original print, borrowed from the University of Tokyo, is well known. The doctored print may be one of a kind, existing today only the Rikken Collection, according to its owner, who told me he bought the print at a certain ukiyoe shop in Kanda. Neatly penned at the bottom of the center sheet of the print is a French title -- "PREMIÈR ATTAQUE Sur Le PONT de KOUMA-MOTO" -- meaning "Major attack at the Bridge of Kumamoto". A cataloger at the print shop was unable to say more about the print except to confirm that it was part of a lot the shop had bought in Europe. She said it was a bit unusual to write a title directly on a print but the practice was not unknown. She said there was no way of knowing who wrote the title, or when or where it was written. It did, however, appear to have been written some time ago. Descriptive titlesI attended the exhibit during its first week. The prints were mounted without descriptive titles. Beside each print was a tag with the name of the series, the issue number, the name of the loaning institution if not from the Rikken Collection, and other such particulars -- but no titles. The owner of the collector called me the following week to inform me that this had caused a huge problem, as some vistors complained about the lack to titles. The museum staff was forced to burn some midnight oil to make descriptive titles. But the prints now had titles. This explained why there were no titles in the book -- neither on the pages showing the images and texts, nor in the table of information at the back. The people responsible for mountaing the exhibition -- the complilers of Chiba 2008 -- had never thought of -- or had thought of but nixed the idea of -- descriptive titles. To be continued. This book is an editorial disaster -- an example of what happens when state-of-the-art printing technology is put in the hands of experts who lose sight of the most important goals of such publications: ease of use and accuracy. Though formally not a catalog, this book was produced and released in conjunction with an exhibition called Yoshitoshi / Yoshiiku no nishikie shinbun: Tōkyō nichinichi shinbun / Yūbin hōchi shinbun zen sakuhin [The nishikie news of Yoshitoshi and Yoshiiku: All works of Tokyo daily news and Yubin dispatch news] -- which ran at the Chiba City Museum of Art from 12 January to 2 March 2008. See Bunmei kaika no nishikie shinbun for a complete examination of the editorial scars that mar this book's superficial beauty. |

| Books and articles related to news nishikie |

Asahi Shinbun Sha (compiler) These two volumes, part of a series celebrating the 100th anniverasy of Asahi shinbun, include a very conservative selection of about four-hundred articles, the earliest from Meiji 12 (1879). The series had ten volumes, including the two under reivew. 1. Love and marriage 2. Exploration and adventure 3. Tokyo at age 100 4. Traces of foreigners 5. Odd stories (1 Meiji) 6. Odd stories (2 Taisho, Showa) 7. Sports features 8. Famous scoops 9. Obituaries (Meiji, Taisho 1) 10. Obituaries (Showa 2) Among the first stories in the Meiji volume is one about a young couple who were unable to exchange "intimate words" because the woman's mother kept a nighlty vigil on her daughter and adopted son-in-law from an adjacent room. The illustration, reproduced from the original report, shows the jealous mother poking her head through the cracked fusuma as the couple pretend not to be doing anything. (Meiji 12, pages 6-7, 8 June 1879) The Meiji volume, like the Meiji era, closes with suicide of General Nogi following the demise of Emperor Meiji. One article eulogizes Nogi (15 September 1912). Another reports a succession of four "mock Nogi" [ese Nogi] suicides that appear to signify a "following-in-death contagion" [junshi ryuko] (18 September 1912). (Meiji 45, page 308) |

Hara Hidenari Forthcoming. |

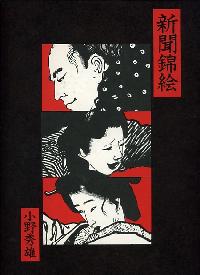

Ono Hideo This large (B4) bible of news nishikie has 121 high-quality full-page reproductions of prints from four series: 82 prints from Tokyo nichinichi shinbun (TNS) drawn by Ochiai Yoshiiku, 22 prints from Yubin hochi shinbun (YHS) drawn by Taiso Yoshitoshi, 4 prints from Kakushu Shinbun Zukai no Uchi (KSZU) drawn by Sensai Eitaku, and 13 prints from Kinsei Jinbutsu Shi / Yamato Shinbun Fuzoku (KJS) drawn by Yoshitoshi. Only TNS and YHS are full-fledged news nishikie. KSZU retells older rather than recent stories. KJS was a newspaper supplement that featured profiles of personalities who had figured in contemporary but mostly not very recent incidents. Collected in the back of the book are full transcriptions of the texts on the nishikie prints, the dates of the newspapers in which the stories retold on the prints first appeared, and sometimes the original or related stories and other commentary. The book begins with brief overviews of the origins of the four series represented in the collection, with information about what is known (and, as importantly, what is not known) about the writers and others who produced the prints. The volume was published by Mainichi Shinbun in 1972, the newspaper's 100th anniversary, a reckoning which starts from the first issue of Tokyo nichinichi shinbun in 1872. TNS was bought by Osaka mainichi shinbun in 1911, and both papers were commonly renamed Mainichi shinbun in 1943. Ono began his collection of news nishikie while employed by TNS, before he became a scholar and pioneered the study of the history of journalism in Japan. (WW) |

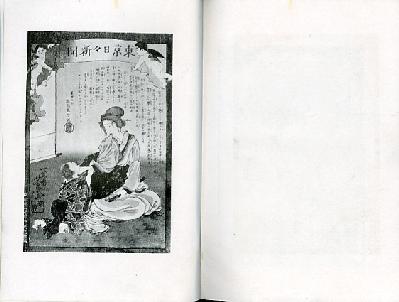

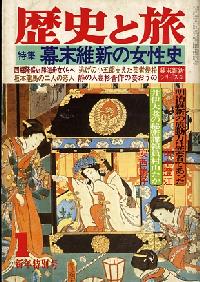

Rekishi to tabi This issue of Rekishi to tabi is the second in a series dedicated to social history in the late Edo and early Meiji period. Of interest to students of news nishikie are two gravure features concerning women involved in crimes and other incidents that attracted the attention of reporters, story tellers, and drawers. Rekishi to tabi This article introduces eight woodblock prints featuring women involved in bakumatsu incidents, including three prints from Yoshitoshi's Kinsei jinbutsu shi series. Hajima Tomoyuki This article introduces five Tokyo nichinichi shinbun nishikie (Numbers 512, 592, 687, 754, 984), three Shinbun jijitsu nishikie (Numbers 1, 3, 7), and four Osaka news nishikie, featuring women who became objects of stories about homicide, suicide, filial piety, or spousal loyalty and the like in the early Meiji period. |

Mark Schreiber This is possibly the first feature article in English dedicated to news nishikie. It was seriously flawed, as the author had not yet done any research on such prints, confused them with newspapers, and ahistorically regarded them as art. Even if his association of early Meiji news nishikie with latterday tabloids were true, the title would have to be "How yesteryear's woodblock tabloids became today's art". See When tabloids were art for a version of this article revised for use on this website. While an improvement over the original article, the revised version still contains a number of statements not supported by evidence. For a more accurate overview of news nishikie, see "News nishikie: An arranged marriage that didn't last". (WW) |

Mark Schreiber News nishikie have definitely arrived when they make the front page of The Japan Times in the 21st century, as did the picture with the Meiji tabloids blurb to the right. This is not, however, a first. The 30 September 1874 issue of The Far East, a photo-illustrated newspaper published in Yokohama by the Scottish British Australian journalist John Black Reddie, is said to have carried the first news report in English about the Tokyo nichinichi shinbun nishikie series (Tsuchiya 2002:105). The article in question, entitled "Art in Japan", introduced TNS-512, the Tonichi nishikie which shows and tells how Kurako defended her father Amano against robbers (Tsuchiya in Kinoshita and Yoshimi 1999:104, n5; see also Meech-Pekark 1986:216, 242 n16). Never mind that practically every claim in the blurb is wrong. By the time readers have turned to page 7, perused Schreiber's finely-tuned story, and studied the (unfortunately) black-and-white illustrations of four prints, they will have realized that (1) Meiji-era writers and drawers were not "freed by the end of the shogunate" because they were never captives, (2) they were less "inspired by western tabloids" than by their own arguably longer and more developed and interesting graphic and narrative traditions, and (3) the artistic stories they created were not "revolutionary" but merely further experiments of the sort they had been freely conducting for the better part of a decade. An updated version of this article will eventually be posted on this site. In the meantime, a full-color web version of the original article continues to be viewable as Just picture that!. (WW) |

First edition (Takahashi 1986)Takahashi Katsuhiko Second edition (Takahashi 1992a)Takahashi Katsuhiko The second (pocketbook) edition is an entirely redesigned version of the first edition. It is by far the most available and least expensive of the very few books ever published on news nishikie. The paper and printing quality is high, and like most pocket books in Japan the signatures are sewn. However, serious students of news nishikie will also want the first (larger) edition. Whereas Ono Hideo's large-format book (see Ono 1972) shows a number of Tokyo news nishikie by Yoshitoshi and Eitaku while focusing on Yoshiiku's Tokyo nichinichi shinbun nishikie, Takahashi's books show over sixty Tonichi prints organized in themes beginning with "Murder" and ending with "People / History" and all but excludes Yoshitoshi and Eitaku prints. In contrast also with Tsuchiya Reiko's study of Osaka news nishikie (see Tsuchiya 1995), Takahashi's books feature more color images and less explanatory text, and are physically much better made. The first edition (Takahashi 1986) contains important articles that were dropped from the pocketbook edition (Takahashi 1992). The pocketbook edition, though, is better designed for viewing, reading, and quick reference. Images and storiesPhysically, the pocketbook features the same news nishikie as the earlier edition. Whereas it shows all news nishikie as full-page color images on smaller pages, the earlier edition presents about half of the prints as full page or double-page color images, and the other half as quarter-page images shown two to a page, some in color, others in black-and-white. Though the pages of the pocketbook are less than half the size of the pages of the first edition, the images are so sharp that the calligraphy on the prints is clear enough to read. In the pocketbook edition, on the page facing the image of each print, is a transcription of the story engraved on the print and a brief commentary on the story. In the first edition, the stories and commentary of the prints shown two on a page appear beside the image, whereas the texts for full-page or double-page prints are gathered together on other pages, where they appear beside thumbnail images of the prints. Explanatory articlesShinbun nishikie no sekai is essentially Takahashi's shrine to Yoshiiku. It features mostly Tokyo nichinichi shinbun nishikie, drawn by Yoshiiku, who Takahashi calls the "principal character" of his presentation. Rather than give his own rundown on Yoshiiku's life, Takahashi included, in the back of the first edition (pp 106-109), a biographical essay called "Ochiai Yoshiiku" by Higuchi Futaba, which appeared in a literary monthly in 1926 (see Higuchi 1926). This article, though, was dropped from the pocketbook without supplementing Takahashi's own remarks about Yoshiiku, and so the pocketbook has conspicuously little information about Yoshiiku. Another feature appended to the first edition is a diagram showing the lineal (master/disciple) relationships between selected late Edo / early Meiji drawers and their descendants among present-day drawer and manga drawers (pp 110-111). The diagram is illustrated with the works of the drawers. For the pocketbook, half of this diagram, sans the images, was integrated into into the article on ukiyoe and girl's manga (see below). Also in the first edition (pp 58-64), but missing from the pocketbook, is a long talk between Takahashi and Sugiura Hinako about the attractions of news nishikie. Sugiura (b1958) was a student of Edo-life documenter and novelist Inagaki Shisei (1912-1996), also read Inagaki Fumio, the pen name of Inagaki Kazuki, aka Inagaki Hidetada. An Edo-period researcher and publicist in her own right, Sugiura is also a manga drawer who has created a number of Edo-period graphic novels that reflect ukiyoe styles. Besides the general introduction to news nishikie, the following three supplementary articles appear in both editions. "Shinbun nishikie to watakushi" "Goshippu bunka to ukiyoe" "Gendai ni ikizuku ukiyoe" All three articles are more profusely illustrated in the first edition than in the pocketbook. The second and third articles, like the discussion with Sugiura, emphasize the continuity of Edo and Meiji life in present-day mass media and manga. (WW) Takahashi KatsuhikoTakahashi Katsuhiko (b1947) is the most prolific and successful promoter of interest in news nishikie. He had been an employee at an art museum, written a guide to the appreciation of ukiyoe, and taught early modern Japanese (Edo) literature at a college before becoming a mystery writer. His debut story, Sharaku satsujin jiken [The case of the Sharaku murders], won the Edogawa Ranpo Prize in 1983. He has also won the Yoshikawa Eiji Prize (1986), the Japan Mystery Writers Association Prize (1987), and the Naoki Prize (1992). His mysteries have involved ukiyoe masters like Sharaku, Harunobu, Hiroshige, Hokusai, and Utamaro, but also European artists like Van Gogh. Takahashi has drawn material for his historical mysteries from stories on drawer prints, including news nishikie (see Ukiyoe misuterii zoon, Takahashi 1991). More recently (Shosetsu Subaru, June 5, pp 364-369), he has incorporated the world of news nishikie, and the gruesome homicide depicted in TNS-933, into an story that will eventually be anthologized as an episode in Volume 4 of his popular Kanshiro hirome tebikae [Kanshiro information notes] historical mystery weries .

It is clear from his approach to news nishikie that Takahashi, like Ono and Tsuchiya, is at least as interested in their stories, as forms of reportage and gossip about human behavior, as in their visual elements. His views are therefore closer to those of students of journalism, sociology, and anthropology than to those of art historians, who tend be more concerned with the purely aesthetic aspects of drawer prints. (WW) |

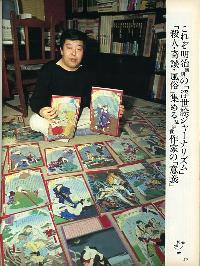

[Takahashi Katsuhiko] The image to right is of the first page of this two-page article on the art historian and mystery writer Takahashi Katsuhiko, who is shown sitting in his study surrounded by part of his collection of mostly Tokyo nichinichi shinbun prints. Takahashi is the best-known and most widely published illuminator of such news nishikie. It is worth noting that the article appears in the sort of weekly magazine that Takahashi argues were preceded by news nishikie in the historical development of tabloidesque photojournalism. Collectors who prefer only the more "refined" and "tasteful" prints usually associated with "Japanese beauty" will probably view Takahashi's interests in the comparatively vulgar news nishikie as culturally scandolous. (WW) |

Toyo Daigaku Fuzoku Toshokan The main feature of this 8-page newsletter, showing Kobayashi Kiyochika's drawer print of the pioneering journalist Fukuchi Gen'ichiro on its cover, is a colorful introduction to the beginnings of newspapers in Japan. The materials used to illustrate the feature are from the university's library. How to enjoy news nishikie An article on news nishikie shows a large picture of Tokyo nichinichi shinbun No. 111. A sidebar by the library staff on "How to enjoy news nishikie" asks two questions:

(1) Who drew the picture? The sidebar directs the reader's attention to the signature in the lower right corner of No. 111, which reads Ochiai Yoshiiku -- a ukiyoe drawer also known as (Utagawa) Yoshiiku and Ikkeisai. In the lower left corner is a signature reading Tentendo Shujin -- an early Meiji gesaku writer whose real name was Takabatake Ransen. A caption explains that No. 111 depicts sumo wresters who have come upon a big fire, and lacking water they pitch in to help demolish the burning structure. The telegraph pole and wires, the reader is told, symbolize the "civilization and enlightenment" of the Meiji Restoration. (WW) The newsletter can be viewed and downloaded as a PDF file from the following link, which will open up in a new window. |

Tsuchiya Reiko This is easily the bible of nishikie news studies, indispensable to any serious student of the subject. Though the book covers and features some Tokyo nishikie papers, it focuses on papers from Osaka. The first third of the main body of the book is divided into chapters on various aspects of nishiki newspapers as a form of visual media in early Meiji Japan. The rest of the main body is devoted to chapters on Osaka nishikie papers, organized by theme, from "Spousal Fights" to the "Seinan War" of 1877 that rocked the new nation and fed its growing news media with so much breath-bating drama. There are sixteen color plates at the front of the book, and the main text is sparsely illustrated with black-and-white pictures, a few full-page, of nishikie papers. An appendix lists editions of nishikie papers with publication particulars. The book ends with a short index and a brief (one-and-one-half page) English overview. This book deserves to be re-issued, but in a higher quality binding that does justice to the heft of its pages, subject matter, and price. Count yourself lucky, though, if you have a chance to buy a copy of this most authoritative tome on nishikie newspapers. (WW) |

Umehara Hokumei (1901-1946), editor Volume 1 [Jo]Folded leaves stitched between soft covers [Wabon] To be continued. |

Volume 2 [Chu]Soft covers, stitch bound [Wabon] To be continued. |

Volume 3 [Ge]Umehara Hokumei (editor) This journal was published in Shanghai. Printed and published 30 October 1927 A third volume of Meiji seiteki chinbun shi (MSCS) was planned but never published. However, part of what Umehara apparently intended to include in volume three appeared in the first issue of Kamashastra, a magazine he helped publish in Shanghai. The article ran 16 pages and consisted of eleven newspaper articles. KamashastraThis first issue of the journal Kamashastra was published on 30 October 1927 in 172 pages. The last of several subsequent issues appeared in April 1928. To be continued. Mark Driscoll on Umehara's activities in ShanghaiMark Driscoll, a student of , is one of very few scholars outside Japan who has taken interest in Umehara's activities. The following papers were presented at the 1999 Annual Meeting of the Association of Asian Studies (AAS), held in Boston on 11-14 March 1999, in Session 166, under the theme "Capital Offenses: Erotics and Desire in Twentieth-Century Japan".

The web version of the abstract of Driscoll's article is worth reading in its entirely, as it helps place Umehara and Sakai Kiyoshi, one of his better known collaborators, in the larger picture of late-Taisho early-showa erotica in Japan and also China. |

Erotic Transnationalism/Grotesque ImperialismMark Driscoll, University of Michigan The historiographic protocols of modernization theory have hegemonized the readings of Japan's imperialism, insisting on a one-way movement of modern power and civilization that initiated in the "West," arrived "late" to Japan, and later still, to Japan's colonies and imperial periphery. Post-colonial theory's insistence on reading the effectivity of the periphery on the metropolitan center, and Deleuze and Guattari's notion of "mutant, decoded flux" of desire flowing back and forth between center and periphery, critically interrogate the uni-directional historicism grounding modernization theory. My paper will examine three of the central figures associated with the so-called "erotic-grotesque-nonsense," arguably the most popular modernist form in Japan from 1925-1935. I argue that the erotic-grotesque-nonsense can be fully genealogized only through the Japanese imperial periphery. Looking first at the case of Tanaka Kogai, one of the most influential sexologists in Japan in the 1920s and the representative erotic-grotesque-nonsense sexologist and metapsychologist, I argue that his tenure from 1896-1904 as the governor-general's chief psychiatrist in Taipei, Taiwan significantly influenced his popular sexology and erotic-grotesque-nonsense texts written later in metropolitan Tokyo and Osaka. Therefore, while reading some of his writings as a colonial psychiatrist, I will look briefly at his metropolitan best-seller called Sex Maniacs (1925). Similarly, I will consider the ero-guro writers, translators (Arabian Nights, Decameron, Sade's Juliette) and editors Umehara Kokumei and Sakai Kiyoshi, who published the influential erotic-grotesque-nonsense monthly Grotesque (1928-1930), as well as its precursor Kamashastra (1927-1928). I will analyze the implications of the fact that Umehara and Sakai published the first erotic-grotesque-nonsense monthly in Shanghai where they moved in 1926, vowing to "bring the ero-guro revolution to China." |

Driscoll, now on the faculty of the Department of Asian Studies at the University of North Carolina, continues to show considerable interest in Taisho/Showa erotica. His contribution to the 2005 AAS Annual Meeting (Chicago, 31 March - 3 April) was entiteld "Hentai = Modernity" and treated "the articulations of a surprisingly "liberal" rendering of hentai (perversion) in Japanese sexology, psychoanalysis and the mass culture discourse of the ero-guro-nonsense in Japan in the Taisho and early Showa periods" (Session 108: Perversion and Modern Japan: Experiments in Psychoanalysis).

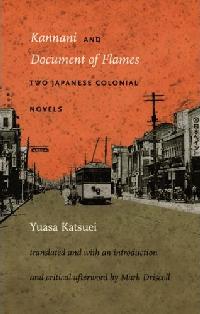

Driscoll's translation of two Yuasa novellasDriscoll, who specializes in Japanese media and cultural studies, and colonialism and postcolonialism in East Asia, recently published the following book, which closely relates to these topics. Yuasa Katsuei The back cover of this important contribution to studies of the period when Korea was under Japanese rule describes Yuasa as follows. |

||

|

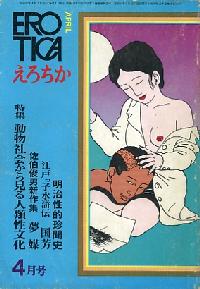

ErochikaMeiji seiteki chinbun shi has gotten very little attention other than in writing about sexology or sexual censorship. Numbers 34 (April 1972) and 35 (May 1972) of Erochika [Erotica], a sexology journal published by Misaki Shobo, has extracts from Volumes 1 and 2. To be continued. |

|

Censorship studies

Umehara Hokumei (1901-1946) was one of the more industrious sexologists of his time -- the "ero/guro" era of the 1920s, spanning the late Taisho and early Showa periods. He was a member of a very small but active society of collectors, translators, and publishers most people in Japan today have never heard of.

Many people would be puzzled, if not outright embarrassed, by the sort of content they would find in Umehara's journals, such as Kaamashasutora [Kamashastra] and Gurotesuku [Grotesque]. Like his compendia of unusual news stories, he distributed limited editions of such publications to interested parties directly, so as not to arouse the censorial lusts of the police and other guardians of imperial morality.

In the review of the Taisho reproduction of Kinsei kyogi den (see Articles), we saw that, by the Taisho period, the graphic violence so commonly found in late Tokugawa and early Meiji woodblock prints was regarded as something shocking. The sexual frankness of woodblock prints, popular novels, performing arts, religious practices, and even some newspaper and magazine fare during the same periods, was likewise not as readily acceptable by the Taisho period and Showa periods.

In one of the prefaces to Meiji seiteki chinbun shi, and in remarks on the colophons, Umehara makes it clear that he is very aware of the risk he was running in publishing a compendium that focused on sex and contained reproductions of graphic images that then, as now, would generally be regarded as pornographic.

To be continued.

Shared discoveries

What makes research truly pleasurable -- despite it being ninety percent sheer grind with little to show at the end of the day -- is the discovery of something that had always been there. What makes it truely rewarding is to share the thrills with those who made it possible.

Does a book exist if no one knows about it?

The main limitation of archival research is that there are simply too many publications, in too many archives, to possibly sift through them all. The main risk of depending on bibliographies and lists of references compiled by other researchers is that many books and articles of possible interest never come into their nets, or they toss back those they consider unimportant.

I have spent some of the best days in my life sitting on the floors in stacks at one or another library, just thumbing through books and journals, searching for something of possible interest -- something I would not know exists until it flashes before my eyes and compells me to take a closer look. It is not that a volume collecting dust does not exist if no one takes it off the shelf and opens it. It is just that its existence has no meaning for someone in whose brain its title and contents have yet to gain entry and recognition.

Eyes and ears of others

Archival research is mostly -- and probably best -- done alone. Libraries are full of people so engrossed in their quest they are barely aware of others. Yet there is nothing more valuable to a lone reseacher than sympathetic colleagues, and even friends of friends, who have some inkling, however vague, about the object of one's obsession.

That we are able to introduce Umehara's work on this website is due entirely to the alertness of Ofer Shagan, a collector of all things beautiful. Shagan knew Mark Schreiber, knew that Mark was interested in news nishikie, and had seen this website.

One day in May 2006, Shagan spotted Volume 1 of the work under review up on Yahoo! Auction. He picked it up for Mark, sent him an image of the cover and another showing the book open to pages which happened to include pictures of two news nishikie, one of which Mark recognized. He promptly called to tell me about the find and forwarded the images to me.

I took the mystery surrounding the identification of the volume from there. Within minutes I had found fragments of information about its publication and contents. I also found the two-volume set pictured and described here, offered by an antiquarian book dealer.

Cracker Jack

We had no idea what the volumes actually contained. The title, and other information I'd found on-line, suggested they were compendia of Meiji newspaper stories of a sexual nature. Yet waiting for them to arrive was every bit as thrilling as digging into a Cracker Jack box, not knowing what sort of toy you're going to pull out.

When I saw that each volume had about 100 stories from newspapers, and about 30 news nishikie with transcriptions of their stories, I knew we had stumbled onto something important in terms of how Umehara used news nishikie, along with newspapers, to reveal the social history of the Meiji period.

Ono, Takahashi, Tsuchiya

Ono in 1972, Takahashi in 1986, and Tsuchiya in 1995 did not mention this compilation or its sequel, Meiji/Taisho kidan chinbun taishusei, which also features news from nishikie alongside news from papers (see review below). Were they not aware of Umehara's work? Or did Ono, Takahashi, and Tsuchiya simply not think his work important?

Tsuchiya calls Meiji no nishikie shinbun [Meiji nishikie news], a 1930 work by Miyatake Gaikotsu (1867-1955), "still today the most detailed catalog of the entire body of nishikie news" (Tsuchiya 1995:16, 2000). Miyatake, pushing 60, wrote about "Tokyo omiyage to shite no shinbunshi" [Newspapers as Tokyo souvenirs" in 1925, the year before Umehara, in nearing his mid-20s, published Meiji seiteki chinbun shi. And the year after Umehara's volumes came out, Miyatake published "Nishikie shinbun no ryuko: Tokyo, Osaka, Kyoto" [Popularity of nishikie news: Tokyo, Osaka, Kyoto].

But whereas Miyatake and Ono Hideo (1885-1977) were both, in the 1920s, writing articles about news nishikie and wondering what to call them as a genre, Umehara spoke of neither "nishikie shinbun" (Miyatake's term, favored by Tsuchiya) or "shinbun nishikie" (Ono's term, at least for those published in Tokyo), but only of "nishikie" (but using "ga" to represent "e"). Whereas Miyatake was a seasoned and already very famous man of Meiji, and Uno was already collecting kawaraban and news nishikie and laying a foundation for studies of journalism in Japan, Umehara was interested only in gathering and collating unusual news stories as raw material of Meiji and Taisho social history. And very unlike Miyatake and Ono, Umehara showed no particular interest in the history of newspaper journalism and woodblock prints.

Still, the extent to which Umehara integrated news from nishikie, into his compilations of news from papers, would seem to deserve at least honorable mention in an overview of Taisho and early Showa retrospectives on Meiji news media.

Sexual reflections

The lithograph at the front of Meiji seiteki chinbun shi aptly reflects the scope of the compilation. The title given in the table of contents is "Dankon nagashi" [Flow of penises]. It shows an oval mirror in which penises are bobbing in a river, while on the banks a murder is in progress, and a policeman is chasing someone, possibly a rapist. The mirror is surrounded by flames and the frame is burning. Glaring over the upper right part of the mirror, from its back, is Konsei Daimyojin, also known as Konseijin, the god of the phalluses and male sexuality.

Konseijin was once worshipped all over Japan at shrines that displayed phallic and ktenic icons of stone or wood. Phallo-ktenic worship is now limited to a few shrines still famous for their festivals. The most spectacular are those in which young women parade a huge phallus, hewn from a log, through crowds of tourists armed with cameras and camcorders. Most such icons disappeared as a result of movements to suppress such public displays of sexuality.

The caption of the lithograph begins with a citation from an article that appeared in the 44th issue of Tokyo nichinichi shinbun, published on 14 April 1872 (Meiji 5-4-8). In the course of describing the picture, the article remarks that recently geisha [geigi] at Ryogoku Yanagihashi, and others, have been enshrining Konsei Daimyojin on god-shelves.

To be continued.

Stories and texts

The two volumes of Meiji seiteki chinbun shi contain a total of about 250 stories, roughly 190 from newspapers and 60 from nishikie. The newspaper stories are presented in order of their date of publication. The nishikie stories are interspered with the newspaper stories.

All the nishikie stories are transcribed in the captions that are associated with the nishikie. The captions also give the name and number of the nishikie. The transcriptions are generally accurate, but Umehara does not reproduce the furigana readings, and sometimes he has changes the okurigana and kanji. For all practical purposes, though, he has simply copied the text on the print.

The great variety of stories imply that, in Umehara's parlance, "sexual" applied to practically every aspect of human relations between the sexes, from infidelity and jealousy, to murder and suicide when provoked by sexual betrayal. But he is also interested in all the ways in which men and women find or leave each other.

Three generations marryA widower covets the wife of a poorer man who had remarried. He offers to buy her, and accepts the other man's condition -- that he also take the woman's elderly father and her daughter by her first husband. The widower accepts because he now has a bride for himself, a bride for his coming-of-age son, and a groom for his widowed mother. This story is clearly "unusual". But it also helps delimit the parameters of "sexual" in Umehara's understanding of the term. |

Cop chases naked thiefLegal and Medical Advisory This has got to be the most completely naked women ever to grace a woodblock print. The policeman's stuffy uniform, and the woman's utterly stichless skin, are truly spectacular contrasts in color. The cherubs seem to be cheering her on. She could well be their mother. The pigment used to color the woman's (and the cherubs') skin is a shade or two pinker that the latterday crayon called "Flesh" in the United States. This label has become politically incorrect in multicolor America but survives as "Hadairo" [skincolor] in polychrome Japan. This print is prima facie evidence that the "yellow" peril is a comorbid condition consisting of paranoid delusions and color discrimination disorder. The policeman, too, is undoubtedly suffering all manner of hallucinations. |

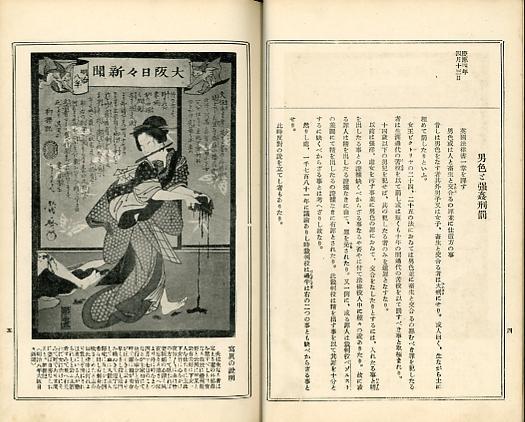

Newspaper illustrationsUmehara reproduced a few of the illustrations that appeared in some of the newspaper stories. Such illustrations increased with the start of Tokyo hiragana eiri shinbun [Tokyo hirigana illustrated news] in 1875, shortly before the demise of news nishikie. The right page of the scan to the right shows the end of a two page story that appeared in the 13 December 1877 (No. 749) edition of Tokyo eiri shinbun [Tokyo illustrated news] as the paper by then was called. Umehara calls the story "Kirisuzume worn by both husband and wife" -- as shown in the picture, in which the woman, who is older, bigger and stronger, is chasing the man and grabs him by the his hair. Summer and winter, they both wore the cheap, thin, nearly sleeveless garmets called "kirisuzume" as they spent all their money and time drinking and fighting, day and night. Everywhere they went they made a general nusiance of themselves and frequently got in trouble. The story ends with the husband paying a 10-sen fine to get his wife out of jail. This particular story was one of the 19 stories from Volume 2 selected for facsimile reproduction in Erochika No. 35 (May 1971, pages 16-17; see commentary above). |

Umehara Hokumei (1901-1946), editor Volume 1 [Jo]Blue leather boards with gilted titles ContentsPreface -- 2 pages, dated New Years 1929 PlatesAll plates consist of one black-and-white image of a woodblock print, printed on one side of a leaf of glossy paper. Of the 22 plates, 17 are photographs of news nishikie. The first 11 plates are interspersed every eight leaves. The first plate comes between the frontispiece and page 1, the second between pages 16 and 17, the third between pages 32 and 33, and so forth, the last between pages 160 and 161. Ten plates (all but the first) show one news nishikie with a caption transcribing its story. The other 11 plates are collected at the end, between the Addendum and the colophon. The last seven show one Tokyo nichinichi shinbun nishikie each with no caption. To be continued. |

Volume 2 (Chu)Black cloth boards with gilted titles ContentsPreface -- None To be continued. |

Volume 3 [Ge]

Commentary forthcoming.

Prints on endpapers

The same prints decorate the endpapers of both of the above volumes. The choice of prints reflects Umehara's selection of stories, which span the whole spectrum of human behavior.

Picture of the New Shimabara Pleasure Quarters in Teppozu in Tokyo

The front endpapers show the middle and left panels of a triptych entitled Tokyo Teppozu Shin Shimabara Yuk[w]aku no zu or "Drawing of the New Shimabara Pleasure Quarters in Teppozu in Tokyo". This woodblock print, drawn by Ichiyusai Kuniteru (c1830-1874), was published in 1869, a year after the facility was built.

"Teppozu" is the common name for the part of present-day Chuo-ku nearest the mouth of the Sumida river. It is situated on the west bank of the river and faces Tsukudajima and Ishikawajima islands.

Teppozu [firearm district] got its name from the fact that, during the Edo period, the area was used for cannon practice by clans holding the Tokugawa government post of Teppokata, which authorized them to manufacture firearms and train government soldiers in their use. Part of the area was also called "Insatsuyagai" [printshop town] because many publishing and printing businesses and workshops were located there.

The New Shimabara Pleasure Quarters was finished in 1868 to provide a controlled place of entertainment for foreigners living in the adjacent Tsukiji Foreign Settlement, which was also opened that year. "Shimabara" was taken from the name of the largest pleasure quarters in Kyoto.

The new entertainment district had some 130 establishments and 1,700 pleasure girls. However, the venture flopped. Not many foreigners in Yokohama had reason to move to Tsukiji, much less frequent New Shimabara, which was closed in 1872. The following year a fire destroyed a number of hotels in the Ginza/Tsukiji area, and train service between Shinbashi and Yokohama began, further convincing foreigners, who could do most of their business in Yokohama, that there was little point in moving to Tokyo. Many of the establishments and denizens of the New Shimabara moved to New Yoshiwara. [Most of this summary was paraphrased from the history of Tsukiji Kyoryuchi (Tsukiji Foreign Settlement) on the Sampomichi Research Center website.]

Fifty [government regulatory] articles in pictures

The back endpapers show a significant part of a triptych called Etoki Gojugo-jo or "Fifty [government regulatory] articles in pictures". The print was drawn by Kikugoe and published by Itosho around the beginning of the Meiji period (seal not yet read).

The print humorously illustrates and comments on fifty regulatory notices [ofure] issued by the government to control various aspects of early Meiji life, from eating beef to socializing with foreigners.

To be continued.

Stories and texts

Commentary forthcoming.

Priest kills womanCommentary forthcoming. |

Widow kills son and selfCommentary forthcoming. |

Lemon sirup and outlaw moneyCommentary forthcoming. |

Blasts of the past

Umehara's collection of unusual news reports from the Meiji and Taisho periods is very convenient today as a source of stories on diverse themes of interest to social historians. In making his collection so large, and in limiting its distribution, Umehara obviously didn't intend it for mass consumption. In fact, the market for Meiji and Taisho nostalgia was inunndated by several smaller and more readily available publications.

One very popular book was Miyatake Gaikotsu's Meiji kibun (see review elsewhere in this Bibliography). The articles on which this book were based came out in 1925 and 1926, and most likely Umehara was aware them. Miyatake had already gained a reputation as a commentator on the more unusual aspects of the human condition.

In the late 20th century, newspaper publishers have used their centennial anniversaries as opportunities to sell nostalgia in the form of multi-volume retrospectives of life in Japan as it has survived in their archives. Most such publications have focused on photographs and other graphic material. Fewer, like Kidan, chindan, kodan (Asahi 1979), have featured mostly articles.

William Wetherall and Mark Schreiber This article introduces six prints through translations of their stories, with commentary on the texts and incidents. The article begins with an overview of news nishikie as a short-lived genre of souvenir prints representing a commercial marriage of convenience between nishikie woodblock prints and newspapers. News nishikie were briefly popular as novelties in an era of novelty. However, their value as commodities quickly dropped as newspapers spread and incorporated illustrations of the kind long familiar to readers of woodblock-printed books and even some late-Edo newspapers. The authors view news nishikie as objects to be understood from the standpoint of those who produced and consumed them -- rather than in terms of "visual news media" theory, which has more to do with present-day academic fashions than with contemporary society. (WW) See "News nishikie: An arranged marriage that didn't last" for a web-version of the entire article. |

| CD-ROMs and other electronic media related to news nishikie |

Tokyo Daigaku Shakai Joho Kenkyujo The cover of the case shows an English title (The Birth of the News / Visual Media in 19th-Century Japan) but nothing else is in English. Instructions explain how to launch the presentation. Items can be selected from a number of prepared topical lists, or from lists generated by keyword searches. Individual items are presented as a thumbnail image beside a database template that displays information about the item, including commentary on the item and transcriptions of stories printed on the item. Clicking the thumbnail displays a medium size image. Another click will display the full image in a PDF file. The medium and larger images, and some of the information associated with the items, including the transcriptions, can also be viewed on the Ono Collection database posted on the web (see Ono Hideo Collection). (WW) |

Tsuchiya Reiko (compiler, annotator) This is the most comprehensive offering of news nishikie images available in any medium. High-resolution images of over 800 prints from a number of museum and private collections. Information on the prints -- including bibliographic data, story transcriptions, and background commentary -- is organized in an almost fully searchable database. Acrobat ReaderThe CD-ROM is operated through an Adobe Acrobat Reader plug-in that is installed by a simple set-up procedure, and all material is presented through the mediacy of Acrobat Reader. All image and text files can be printed through Acrobat Reader. Text files on the CD-ROM can be opened and captured in a text editor. However, images are embedded in password-protected PDF files to prevent capturing. One work around is to capture the screen (including offscreen portions) and then crop out the image. The CD-ROM includes images all of the Tokyo nichinichi shinbun (TNS) and Yubin hochi shinbun (YHS), and other news nishikie, that are listed in tables appended to Tsuchiya's Osaka no nishikie shinbun. A majority of the TNS images are attributed to prints in the Araya Bunko (Mainichi Shinbun). All other TNS images are attributed to the Nishigaki Bunko (Waseda University). No TNS images are of prints in the Ono Collection (Tokyo University). YHS images are attributed to many sources, but again not the Ono Collection. Other news nishikie reference materials also suggest that there are several fairly large collections of TNS prints but fewer large collections of YHS prints. BlurbsAll the TNS and YHS scans have a blurb at the top in Japanese, Romaji, and English. As the following examples show, the romaji is kunreishiki, and some of the English is barely understandable.

Database recordsWhile a given image file is being displayed, clicking an icon on the task bar will open a window that displays the database record associated with the image. Clicking a field will display the content of the field in the window. The fields include two choices of transcription, and the drawer, writer, publisher, date, and a "memo" field that is almost always empty. TranscriptionsThe default field displayed in the database window is a transcription of the text on the print, including (in parentheses) all furigana (rubi) readings. One can also choose a version of the transcription without the rubi. The records of many prints also include a transcription of the original story. All these texts can be displayed, and printed, horizontally (default) or vertically. Text files of stories and original articlesText (filename.txt) files of the transcriptions are in the "chushaku" folder on the CD-ROM. The files in the "yomi" sub-folder are the full transcriptions of the stories with rubi and are the ones that should be used when translating. The files in the "yomi2" sub-folder do not include the furigana readings, which are crucial to understanding intended pronunciations and even meanings. Transcriptions of original articles, when available, are in the "sansho" folder. Bitmap files of seals, signatures, and other particularsThere are thousands of bitmap (filename.bmp) files in the "thumbs_b" directory on the CD-ROM. There are individual files the date seals or date stamps, drawer signatures and seals, publisher information, and other particulars, for each print. These files are vieweable while examining images and associated database records. But like the text files, they can also be opened, or copied, directly from the CD-ROM. Overview articleIn the overview article, names of drawers, writers and publishers for which information is available in the database are hot linked to database records that feature more information. Cliking "Gusokuya", for example, will take you to more information about this publisher than is generally available on the Internet or other news nishikie sources. Tables of printsThe table of prints is more exhaustive than any found elsewhere. Unlike the tables in the back of Tsuchiya 1995, the tables on the CD-ROM include seal dates and also the dates of the original stories when available (as they are for most TNS and YHS prints). The tables are divided by place of publication, and Tokyo prints come first. Navigation and searchingWhile the navigation is a bit unfriendly, this CD-ROM is a very valuable resource. Records can be searched by clicking preselected keywords on topical menus, and there are numerous such menus in Japanese and English. Records can also be fairly freely searched by Boolean queries. Accuracy and reliabilityTsuchiya is named as responsible for "compilation" (henshu) and "commentary" (kaisetsu). However, the content of the database was developed and vetted by over a dozen others. And it appears that no one sat down and crosschecked every detail with a mean and merciless eye for errors of commission and omission. As a result, there are enough discrepancies that careful researchers will want to use any information on this disk without crosschecking with the original. Still, this CD-ROM database is a remarkable achievement, and Tsuchiya deserves every bit of the recognition she has received for its production. (WW)

Further information in Japanese |