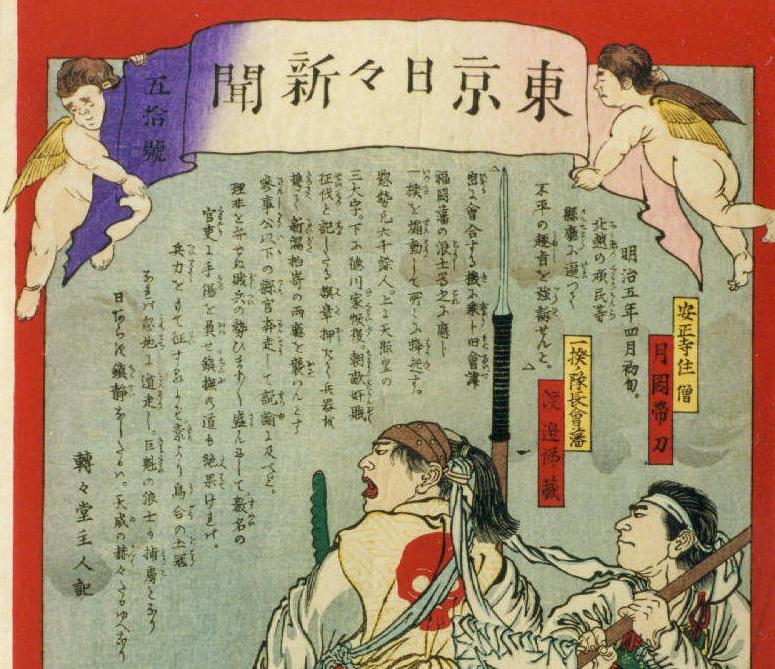

Print informationNameThe masthead consists of two chubby cherubs holding a banner at either end. Read more about these plump putto, speculation about their origin and variation in news nishikie, and related art problems in Cherubs and Banners. Titles in cartouches on woodblock prints rarely ran horizontally. When they did, like this one, they read right to left -- the directional convention for horizontal titles and headlines until sometime after World War II. The kanji read Tokyo nichinichi shinbun -- the name of the newspaper which ran the original Hokuetsu riots story in the spring of 1872, a couple of months after it began publishing. This nishikie, though, was printed in the fall of 1874. Later we will ponder why this story was chosen for resurrection in a news nishikie. News nishikie in Tokyo, though not newspapers and not published by newspaper companies, typically bore the name of the newspaper from which they took their stories. Or they were some combination of "shinbun" (news) with "zukai" (illustration). In Osaka, which did not have its own daily papers until late 1875 and early 1875, news nishikie names were usually some combination of "Osaka" with "nishikie/ga" and "shinbun" (news) or "shinbunshi" (newspaper). Some Osaka news nishikie had "nichinichi" in their title, in emulation of daily papers. Though some scholars call Tokyo varieties of news-related nishikie "shinbun nishikie" (news nishikie) and their Osaka cousins "nishikie shinbun" (nishikie news), both are referred to on this website as simply "nyuusu nishikie" (news nishikie). See On "nishikie shinbun under Articles for further discussion of this and other terminology problems. Issue number and date of storyThe numbers on most news nishikie with actual newspaper names, like Tokyo nichinichi shinbun and Yubin hochi shinbun, are the issue numbers of the paper which ran the articles that inspired the nishikie stories. The issue numbers jump, and many issues with lower numbers were printed later than issues with higher numbers. News nishikie with non-newspaper names, however, were generally numbered serially, beginning from No. 1, without regard to the issue numbers of the newspapers from which they may have obtained their stories. The number on the print being introduced here, which I have dubbed Hokuetsu riots, appears on the purple fold at the left of the banner as three kanji reading Number 50. However, the Hokuetsu riots story was reported in Issue 48 of the paper, and so the number on the nishikie is wrong. Does this make it more valuable, like the stamp with the inadvertently inverted biplane? Unfortunately, this analogy doesn't fly. It doesn't stick either. If the publishers noticed the error, they never corrected it. Misnumbering comes to light when tracing the original article, as Ono Hideo did for his beautifully illustrated 1972 book called Shinbun nishikie. For each print he shows in the book, Ono gives the date of the issue of the paper in which its story was originally reported. In addition to transcribing the story on the print, he sometimes cites and comments on the original story. Regarding the story on the "Hokuetsu riots" print, he observes that it was reported in the Meiji 5-4-13 (19 May 1872) edition of Tokyo nichinichi shinbun, which was Issue 48, not 50. Only a few news nishikie were misnumbered. Tsuchiya Reiko has noted some errors in tables of known news nishikie prints in the back of Tsuchiya 1995, and other errors on Tsuchiya 2000, a CD-ROM which has images of most known prints.

DrawerThe signature and seal of the drawer appear above the foot in the lower-left corner of the print. Here Yoshiiku signs as Ikkeisai Yoshiiku, his most common signature on TNS prints, closely followed by Keisai Yoshiiku. He signed only a couple of TNS prints as Ochiai Yoshiiku, the name by which he is most widely known. Yoshiiku signed the drawing, and so his signature was carved into the block. The seal, also printed, reads just Yoshiiku. Yoshiiku drew all of the numbered TNS prints. Two unnumbered triptychs were drawn by Seisai Yoshimura, and another was drawn by Hayakawa Shozan, a year or so after Yoshiiku moved on to other projects. PublisherThe three kanji written vertically in the box on the red border immediately to the left of Yoshiiku's seal read Gusokuya, the name of the publisher who produced the first-runs of all Tokyo nichinichi shinbun nishikie. The three kanji written in a somewhat stylized manner, right to left immediately above the publisher's name, read Ningyocho, the location of the print shop. CarverThe carver's name is Katada Horicho. Carvers, engravers, and tattoo drawers today commonly adopt a handle beginning with Hori, which means carve or engrave. Most TNS prints were carved by Watanabe Horiei. Carvers were practically as mobile as artists. Watanabe Horie, affiliated mainly with Gusokuya, carved about 80 of the roughly 110 prints in Yoshiiku's TNS series in 1874 and 1875. At the same time, he carved most of Yoshitoshi's Meiyo shindan drawings for Gusokuya in the fall of 1874, and three of Yoshitoshi's Yubin hochi shinbun (YHS) news nishikie drawings for Kinshodo in early 1875. Katada Horicho did the blocks for seven TNS and two YHS drawings. |

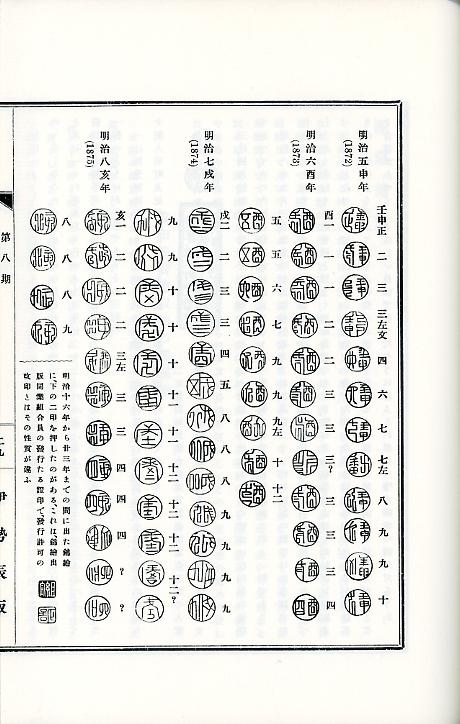

Seal of approval and date of printWhen was Hokuetsu riots published? Before numbers 1 and 3, and after number 472. Make sense? Only if you keep in mind that, by 1874 when plans were announced to publish a nishikie version of stories selected from Tokyo nichinichi shinbun, the newspaper, the paper had been coming out every day for over two years. Except for the Taiwan Expedition and a few other "breaking news" developments, the nishikie stories didn't appear in a particularly timely manner. Though nishikie Number 50 should be Number 48, and Issue 48 of Tokyo nichinichi shinbun was published on 19 May 1872, we know that the nishikie was printed around September 1874. How? Because, immediately above the publisher's cartouche is the seal of approval of the official who inspected the drawing before it was carved and just before it was printed. If you study the seal, then compare it with the seal at the very bottom of the middle row of the table of seals in the image to the right (click to enlarge it), you will see that the seal was used in the 9th month of Meiji 7, or September 1874. The "aratamein" or "kaiin" (‰üˆó), as the seal is called, gives us only an approximate earliest date of the print. The printing could have been delayed for a while after approval. And the print could be from a batch that was printed a few months later in response to demand for more copies. Not all early prints have an approval seal, however, so count your blessings when you see one. One year later, in September 1875, the publishing edict of 1869 was heavily revised. The pre-publication inspection system, which had begun during the Tokugawa period, came to an end. Publishers were now required to print the year, month, and day of issue on all publications, including some woodblock prints. |

PictureThis is one of the brighter and more colorful of the Tokyo nichinichi shinbun nishikie, or any news nishikie for that matter, thanks to the abundance of white with the light yellow and green, and the smatterings of red, black, brown, and blue. ImpressionThe impression of this print is particularly good. The registration, where colors meet at a black line, is very clean. The impression and colors of a print can suggest that it came from a later printing. Second, third, and later printings inevitably reflected physical changes in the blocks as they were used in one printing, then washed, dried, and used again in a later printing, possibly by a different printer using different inks. See Woodblock Publishing for more about how woodblocks prints per published, from conception to printing and distribtuion. PerspectiveYoshiiku uses perspective to great effect here, putting the bamboo staves between us and the men, warning us not to approach them. The banner is also more conspicuous because it is closer to us, and the warrior is more prominent than the priest. Yoshiiku uses the same technique, though the perspective effect is not as pronounced, in Sumo Firemen to draw our attention to the telegraph poles and lines in the foreground. Dramatic elementsYoshiiku captures the Buddhist priest and Aizu warrior from an angle intended to show the skull on the back of the warrior's blouse, and the slogans on the banner erected behind him. His mouth is open and we can hear his demands. We have no doubt he means business and would not want to be on the receiving end of his anger. The slogans on the banner tell us what he might be saying. He seems to be inspired by Amaterasu, the progenitor of the imperial family. This does not mean he supports the Meiji Restoration, but simply that he is not opposed to the imperial family. The slogan on the right tells us very clearly that, in fact, he would rather there had not been an imperial restoration, that power should be returned to the Tokugawa clan. The other slogan tells us he thinks traitors should be punished. |

StoryHere we will look at the writer, writing, language, structure, and selection of Hokuetsu riots as a work of journalism and moral instruction. A complete translation of the story and commentary on its background and significance appear on the foregoing link. WriterThe scan of the top half of Hokuetsu riots shows the story in greater detail. To the left of the story, in bolder script, is the name of its writer, Tentendo Shujin. Tentendo was the gesaku writer Takabatake Ransen. He wrote most of the earlier stories, and all of the later stories, on TNS prints drawn by Yoshiiku. The gesaku writer Jono Denpei, writing as Sansantei Arindo, was second most frequent writer of Yoshiiku's TNS stories. In April the following 1875, about half a year after the Hokuetsu riots nishikie came out, Yoshiiku and Takabatake started Hiragana eiri shinbun, Japan's first illustrated newspaper. Written for the kanji-challenged masses, mainly in kana and full of black-and-white pictures drawn by Yoshiiku, the paper quickly became very popular. By fall they had stopped producing Tokyo nichinichi shinbun nishikie, and in December Takabatake moved to the Yomiuri shinbun, which began publishing a newspaper in November.

NarrativeNote that the text of the story is integrated into the picture. This was a common practice on nishikie series in the 1850s and 1860s, particulary series that featured famous and infamous historical figures. The drawers and writers of news nishikie in the 1870s were well-versed in this practice of integrating the narrative with the image, though some news nishikie enclosed the story in a rectangular cartouche. LanguageNote that most of the kanji (Chinese graphs) are provided with furigana (rubi) readings for the benefit of people who could read kana (moraic script) but had less facility with kanji. Furigana also clarified the readings of unfamiliar place and personal names. The furigana for some kanji specified their pronunciations in Japanese rather than their readings in Sino-Japanese. This practice was an attempt to vernacularize the narrative -- i.e., tell the story in a manner more familiar to the ear than the eye. This is not imply that Sino-Japanese readings would not have been understandable if heard without recourse to visual confirmation of the text. Contrary to a popular myth sometimes repeated by scholars, alleging that Japanese writing heavily depends on the eye to be understood, practically all Japanese texts are understandable as language -- i.e., as they would be understood if only heard and not read. This is true because kanji in Japanese, like hanzi in Chinese, are essentially morphemic elements, deeply rooted in language, meaning speech. Otherwise such graphs would be useless as script with which to represent sounds that are meaningful to the brain that hears them through the ear. However, script itself is visual, and the brain behind the eye can either decipher it into the language it is meant to encode, or not. And news nishikie texts are not "reader friendly" by today's standards. The kana orthography is "old" or "historical" by "new" or "present-day" standards. Imagine -- to use the simplest anaology -- learning "nite" and "thru" in school today and suddenly encountering "night" and "through" in a 19th century publication. Kanji used to signify verbs are not always followed by okurigana, which means the reader has to supply conjugations from context. Some kanji and kana are abbreviated or written in what are best described as "standard non-standard" forms. (Ono 1972:6) When introducing news nishikie stories in their books, scholars like Ono Hideo, Takahashi Katsuhiko, and Tsuchiya Reiko have sometimes transliterated the original texts for the benefit of present-day readers. However, both the Ono Collection Database and its CD-ROM, and the Bunsei Shoin CD-ROM I am calling Tsuchiya 2000, have full and fairly faithful transliterations of the original texts. StructureLike most nishikie stories, Hokuetsu riots is told in the manner of a news report, beginning with a lead and answers all the basic questions -- when, where, who, what, how, and why. But it also addresses the "so what" of the incident, in the manner of an editorial or op-ed. Unlike straight news, which strives to describe without moralizing, news nishikie stories are intentionally illuminated by moral commentary. The structure of the Hokuetsu riots story is shown in the following table. Parts in boldface are from the nishikie version. Parts attributed to Ono Hideo are from the newspaper version or from an article in Shinbun zasshi, another news pamphlet Ono both cites and paraphrases. Unattributed parts include information from other sources and my own commentary. |

|

When |

The 1st third of the 5th month of the 5th year of Meiji -- the middle of May 1872. The uprising began on Meiji 5-4-4 -- 10 May 1872 (Ono 1972:147). |

|

Where |

Hokuetsu. Niigata and Kashiwazaki prefectures. Prefectural halls. |

|

Who |

The "obstinate people and others of Hokuetsu" (Hokuetsu no ganminra) and disenfranchised Aizu-Fukuoka samurai. Frustrated farmers, disgruntled Buddhists, and alienated former samurai. |

|

What |

Over 6,000 people besieged the prefectural halls. Three or four thousand peasants stormed Kashiwazaki's prefectural hall. From there the movement spread to Niigata. As they moved through the countryside toward the prefectural capitals, the rioters burned some barns and storage sheds. As many as 20,000 people were involved. Violence erupted when some of the leaders were arrested. The captain of the rebels and one official were killed. Four rebels were seriously wounded, and other people, including some officials, sustained light to heavy wounds. There was some concern about the safety of a foreigner who was residing in the region. (Ono 1972:147). The uprising began in Kanbara, then a town in Kashiwazaki prefecture, now a city in Niigata. |

|

How |

The peasants were led by disenfranchised samurai from the domains of Aizu and Fukuoka. Officials suppressed the riot with military force only after they had exhausted "the path of placation" (chinbu no michi). The samurai were remnants of pro-Tokugawa factions that imperial forces had subjugated four years earlier. Since then, all domains in the country had been prefecturized, and samurai had lost their privileged status, including their right to carry swords. Yet there were still pockets of anti-imperial resistance -- idealists, grudge bearers, and opportunists looking for chances to stir things up and revolt against the new government. |

|

Why |

The rioters had complaints. The farmers were unhappy about their economic conditions. The priests were unhappy about the official embrace of Shinto at the expense of Buddhist power. The samurai were unhappy about the loss of their domains and the privileges they had enjoyed under the Tokugawa shogunate. |

|

So what |

The "glory of imperial authority" (ten'i no kakukaku) brings peace. Imperial authority is righteous and benevolent. It is the foundation of the state, and the state will not countenance rebellions by seditious ruffians. Bear this in mind the next time you think about joining a mob and marching against the imperial state. |

SelectionWe would be remiss not to ask why, of all the stories published in Tokyo nichinichi shinbun, a particular story should be chosen for a nishikie version. This question becomes especially important when the story is two years old and involves a continuing and serious political threat like seditious elements that are able to spark peasant rebellions in disaffected rural areas. Some of the stories selected from earlier issues probably reflect the personal interests and whims of Yoshiiku and his writers. One can imagine Yoshiiku waking up one morning with an urge to draw some blood (there's more than one way). He remembers a story that ran in the Tonichi (newspaper) a few months ago. He and Tentendo jankened for who got to choose the next TNS (news nishikie) story, and Yoshiiku won.

But what about the story of the Hokuetsu riots? Whose call was it, and why? Neither Yoshiiku nor Takabatake are known to have been particularly political persons. Yet they were able, ready, and willing to repeat the mantras of the imperial order they appear to have supported. And they were in good company at Tokyo nichinichi shinbun, which evolved into an even more pro-government paper after the loyalist Fukuchi Gen'ichiro became its chief editor that summer of 1874. The spring of that year had witnessed a nasty rebellion in Saga, which had left many people dead, some executed, like Eto Shinpei, who had recently been the Minister of Justice. Satsuma, also in Kyushu, was another hotbed of disaffected former samurai who were ripe for a fight, in Japan if not Korea or Taiwan. In fact, a Kyushu-mounted expeditionary regiment had gone to, saw, and conquered a whole tiny village of Taiwanese savages that spring for having greeted some shipwrecked Ryukyuan (Okinawan) fisherman with death in 1871 -- and Tokyo newspapers and news nishikie were championing the overdogs all the way. What went through the minds of Yoshiiku and Takabatake as they produced the Hokuetsu riots print will never be known. Whatever they thought, their graphic and verbal narratives suggest they probably sympathized with the forces that quelled the riots and brought the "glory of heavenly authority" to the ignorant and stubborn masses -- just as the Japan had begun to spread the August Mercy of the August Realm of Emperor Meiji to Taiwan. What was good for the nation was good for the rest of Asia. And the publishers and artisans of the woodblock industry contributed their own mass and energy to the gathering momentem toward imperial order throughout the region. |