Commentary

The incident reported in this story is a vehicle for the much longer commentary in which it is wrapped. The commentary is a humorous, even satirical take on "transformations" that defined the "enlightenment and civilization" at the start of the new "realm" of the imperial restoration.

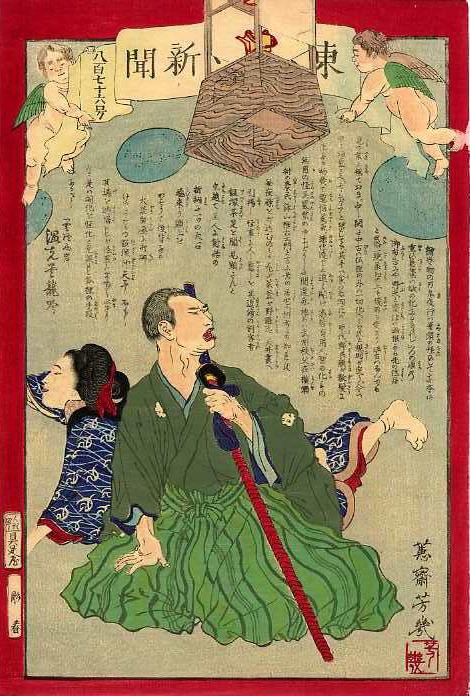

The gentleman depicted in the drawing appears to be the swordsman Iizuka, astonished by a mystery even his cropped head (see notes) was unable to fathom.

See TNS-909 Man becomes tanuki for another story of strange phenomena reported from Yokose village.

Notes

This is one of more convoluted stories in the TNS nishikie series. The structure of the lead is a good example of the trouble to which the writer goes to be both profound and funny.

絵巻物の百鬼 (き) 夜行ハ筆頭 (ふでさき) の怪 (くわい) にして赤本の重 (おも) ひ葛篭 (つゞら)ハ欲 (よく) の化たるなるベし

Emakimono no hiyakuki yagiyau [hyakki yagy#ō] ha fudesaki no kuwai [kwai, kai] ni shite akahon no omohi [omoi] tsudzura [tsuzura] ha yoku no baketaru naru beshi"

A は B にして C は D なるべし

A being B, C must be D

Taking A to be B, it follows that C is D

Hundred demons night parade 百鬼夜行 (Hyakki yagyō) refers to a well-known picture scroll by this name, which depicts all manner of folkloric beings and beasts moving in a procession at night. The term used her to classify the work as a "picture scroll" is 絵巻物 (emakimono) -- or "picture scroll genre".

Numerous representations of the procession are found in scrolls and single prints. The most famous scroll, a 16th-century work, is attributed to Tosa Mitsunobu (土佐光信 circa 1434?-1522?/1525?), founder of the Tosa school of Chinese-style painting.

The Hundred demons night parade of the picture scroll genre, being a mystery of the head of a brush, a heavy vine box of red books must be [mystery which has] transformed into greed.

red books, reflecting 赤本 (akahon), were story books with red covers -- opposed to "black books" (黒本 kurohon) and "blue books" (青本 aohon), and "yellow cover-paper" (黄表紙 kibyōshi) books. All such books were woodblock printed on pages bound in folio style. Most were to some extent -- some elaborately -- illustrated. Longer stories were published in multiple volumes.

Red books flourished in the early decades of the 18th century. Blue books, which had light bluish or yellowish green covers, came next and continued into the 19th century. Black books briefly flourished in the middle of 18th shortly after the appearance of blue books.

Content wise, red books were mostly otogibanashi (お伽噺) like Momotaro, and other fables about rivalries in the larger animal world, which could be told to children. Blue and black books were mostly tales of the historical and legendary sort that were popular on kabuki (歌舞伎) and jōruri (浄瑠璃) stages.

mystery reflects 怪 (kuwai, kwai, kai) -- which figures five times in this story -- once by itself (read "kwai"), once in 怪異 ("kaii" read "bakemono"), twice in 怪事 ("kaiji"), and once in 怪化 ("kaika") -- all of which see below.

transformed reflects 化たる (baketaru). This, with "mystery" (径 kai), sets up the "transformation of mystery" (怪化 kaika) pun at the very end of the story (see below).

vine box reflects 葛篭, which graphically represents "tsuzurako" -- 葛 (tsuzura), a kind of vine, the strong fibers of which were used to weave the earliest such boxes -- and 篭 (籠 kago, ko), a basket, box, or trunk. Here, though, the compound is glossed just つづら (tsudzura < tsuzura), the more common term for such wickerwork containers.

While some tsuzura were made from the woven fibers of the vine of this name, most were made of bamboo, and a few were made of cypress (hinoki). The woven surfaces were often covered with washi (Japanese paper), and the washi was then lacquered, which strenthened and sealed the container. Though widely associated with kimono, tsuzura could be used to store anything -- including, as here, printed matter.

official proclamation reflects 御布告 (go-fukoku), the contemporary term for a decree which had the force of a law or ordinance, issued by the Great Council of State (太政官 Dajōkan).

society reflects 世俗 (seken) -- "sezoku" in Sino-Japanese, but here 俗 is glossed けん (ken) -- either meaning society, social customs, or ordinary people.

boors and ghosts reside on the other side of Hakone reflects 野夫と変化ハ函根から先の住居 (yabu to bakemono wa Hakone kara saki no sumai).

野夫 (yabu) graphically means a "rustic man" -- a ruralite who sophisticated city folk view as unrefined, uncouth, boorish. The term is synonymous with 野暮 (yabo) -- a state of being ignorant and unrefined, or such a person.

The source of the expression is 野暮と化け物は箱根から先 (yabo to bakemono wa Hakone kara saki) -- meaning "boors and ghosts [are] on the other side of Hakone" -- said by Edoites who, proud of their big-city breeding, believed that unsophisticated people and the objects of their superstitions existed elsewhere.

先 (saki) means "ahead" when used in reference to the direction one is traveling -- hence, if heading toward Hakone from Edo, and speaking of "from" Hakone, it would be the "other side" -- meaning places like Osaka. Hakone was the divide between Kantō (関東) and Kansai (関西), respectively "east" and "west" of the Hakone Barrier (箱根関 Hakone no Seki), a checkpoint at Ashinoko lake in the Hakone mountains, through which travelers on the Tokaido, the general name of a network of roads that connected Nihonbashi in Edo with Koraibashi in Osaka.

The term "yabu" is also graphed 野巫 (yabu), meaning a rustic [rural, country] 巫医 (fui) -- a fusion of 巫 (miko) and 医 (kusushi) -- a spiritual medium cum medicine man -- a person who healed with prayers. "Fui" was sometimes used as a metaphor for a zen monk of inferior training and practice (Kojien). With the introduction of scientific medicine, "yabu" came to mean "quack" or "charlatan" as in 藪医者 (yabuisha) or "yabu doctor" -- in which "yabu" is graphed 藪 -- a thicket or bush.

remote past reflects 往古 -- "ōko" in Sino-Japanese but glossed simply むかし (mukashi).

somewhat opened middle past reflects 少し開た中古 (sukoshi hiraita mukashi), in which 中古 -- "chūko" in Sino-Japanese -- is also glossed simply むかし (mukashi). 開た (hiraita) reflects the 開 of 開化 (kaika), meaning "civilization" in my approach to this term (see below). It means "opened" or "unfolded" as in "civilized" or "developed" -- or "enlightened" in terms of the more conventinal English tagging.

reign of civilization reflects 開化の聖代 (kaika no miyo). Here 聖代 -- "seidai" in Sino-Japanese -- is glossed ミよ (miyo), a Japanese expression usually graphed as 御世 (miyo) or 御代 (godai, goyo, miyo). There is also 聖世 (seisei). These terms refer to either the imperial reign or to the realm ruled by supreme emperor. Though 代 and 世 somewhat overlap and at times are conflated, 代 is closer to "era" and "reign" while 世 is more like "world" and "realm".

開化 is graphically played out in transformed (化た baketa) and spread (開け hirake). "Transformed" is further played out as ghosts (化もの bakemono) and the mysterioius. See note on "civilization" below for how I am treating 開化 (kaika) in this translation.

squirrelman reflects モモンガア (momongaa), which was also written モモングワア (momonguwaa, momongwaa). The derives from ももんが (momonga), a type of flying squirrel. Here it means ももんじい (momonjii) -- a hairy aparition or bogeyman who, looking like a big version of such a squirrel, carries children off into the woods. A parent might say something like 早くねんねしな、ももんじいが来るよ (Hayaku nenne shina, momonjii ga kuru yo) -- "Go to sleep now, or the momonjii will come!" (Kojien).yaro heads transformed into cropped hair [heads] reflects 野良頭が散髪に化た (yarō atama ga zangiri ni boketa), meaning the older "yaro atama" style metaphorphized into the "zangiri" or "zangiri atama" (散切り頭) style that become fashionable among men after 1871, when samurai and others who had been obliged by their status to wear topknots were free to cut their hair, thus ending such distinctions.

"Yaro heads" refers to the hair style of the young male actors of "wakashū kabuki" (若衆歌舞伎), which came into vougue during the early decades of the 17th century after women were banned from kabuki, partly because of prostituion.

By the middle of the century, stylish young kabuki actors, who wore their hair in the "yaro atama" style, were also banned from the stage, again partly because of implications of prostitution -- kabuki being then a popular theatre which was used as a stage for a number of underground practices the government wished to suppress.

See note on cropped hair in TNS-813 Boy raised as girl for more details about this style of hair in the Meiji period and now.

ghosts and the mysterious reflect the graphic differences between 化 (ばけ) もの and 怪異 (ばけもの), which are both marked to be read "bakemono". The former would ordinarily be read "bakemono" in Japanese, while the latter would usually be read "keii" (also written 魁偉) in Sino-Japanese. Here the latter may be taken to graphically explain the former. In other words, "ghosts" are among the "mysterious" or "strange" (if not the "suspicious" or "dubious" or "questionable") phenomenon which are being prohibitted.

farmer reflects 農民, ordinarily read "nōmin" (farmer < agricultural folk) but here glossed ひやくしよう (hyakushō), which is usually graphed 百姓 or "hundred surnames" -- a Chinese term can mean anything from the general population under heaven, to farmers as a rural class.

Yokose village (横瀬村 Yokosemura) was located in what is now the town of Yokozemachi (横瀬町) in Chichibu county of Saitama prefecture. Bushu (武州 Bushū) was otherwise known as the province of Musashi (武蔵国 Musashi no kuni).

mysterious incidents reflects 怪事 (kuwaiji > kwaiji > kaiji) -- "kwai" as in the "Yotsuya kwaidan" (四谷怪談).

foxes and raccoon dogs reflects 狐狸の手段 (kori no shudan). Foxes (狐 kitsune) and raccoon dogs (狸 tanuki) are the famous in Japanese folklore are commonly cast as tricksters in folklore.

See note on tanuki in TNS-909 Man becomes tanuki, also set in Yokose village.

"civilization and mystification"

erringly seen civilization as mystification reflects 開化を怪化と見誤りし (kaika o kaika to miayamarishi).

The two "kaika" compounds are represented by "civilization" and "mystification" merely to facilitate the humor in English. The phrase actually means that foxes and raccoon dogs have "erringly seen development [of the country] as [a matter of devising more] strange [incidents] and ghostly [appearances]".

civilization

開化 (kaikwa, kaika) is the second part of 文明開化 (bunmei kaika), a slogan which practically defined the Meiji period -- usually (and benignly) translated "civilization and enlightenment".

Though 文明 (bunmei) is the term most widely used to mean "civilization" -- it is in fact metaphorically closer to "enlightenment" in the sense of "illumination" (明) through "literature" (文). Whereas 開化 (kaika) means to "open" (開 kai, hirakeru) and "change" (化 ka, bakasu) -- as in settle, cultivate, and otherwise transform -- hence "civilize" -- lands and people.

mystification

怪化 (kwaikwa, kaika) was a compound of 怪 (kai) -- something strange, incredible, weird, mysterious, and therefore possibly suspicious or freightening -- and 化 (ka) -- the result of a change or transformation -- a changeling, ghost, apparition.

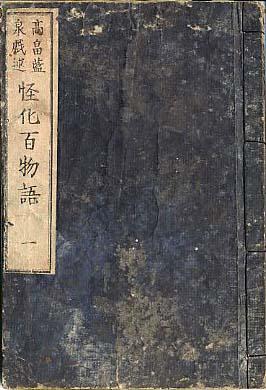

The compound was used in the titles of a number of Meiji works, including a collection of stories, by Takabatake Ransen, published at the time this print was produced (see below).

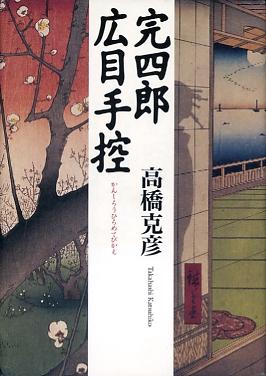

Today, too, the two "kaika" are sometimes swapped in wordplay, as in a novel by Takahashi Katsuhiko (see below).

Takabatake Ransen's "Kaika hyaku monogatari"The term "kaika" was well-known to TNS story writers. The most prolific was Takabatake Ransen (1838-1885), who by the time this print was produced had published a collection of stories entitled Kaika hyaku monogatari (怪化百物語 kuwawi kuwa hiyaku monogatari > kwaikwa hyaku monogatari). On the surface the title could be translated "One-hundred tales of the mysterious and changed". As a pun, "kaika" could also be seen as meaning "mysterious change" in the sense of "civilization as mystification". See 100 tales of kaika and kosetsu: Mysterious change and towntalk in Meiji and Heisei Japan in the Articles section for more images and a fuller account of this early Meiji work by Takabatake, and for a look at the Meiji volume of Kyōgoku Natsumehiko's Kōsetsu hyaku monogatari series, a Heisei work. |

Takahashi Katsuhiko's "Bunmei kaika"高橋克彦 Takahashi Katsuhiko This is Volume 4 of the Kanshiro hirome tebikae series. The first volume introduces Kanshiro as a disenfranchised samurai who becomes a "hiromeya" (広目屋) -- an informer, promoter, or publicist along the lines of a present-day advertising agent. Kanshiro is tight with social outcastes like the gesaku writer Kanagaki Robun -- and, through Robun, popular sketch artists and illustrators like Yoshiiku and Yoshitoshi -- who, in 1874 and 1875, when "Bunmei kaika" unfolds, are busy drawing the woodblock prints which convey reports of the incidents that involve Kanshiro as an amateur detective. See Kanshiro hirome tebikae: Takahashi Katsuhiko's Heisei gesaku serial for an introduction to the entire series. |