Photographic stories

Composing moments in life

By William Wetherall

First posted 18 December 2015

Last updated 6 January 2022

View finding

WYFIWYMGTSOWTWOWYTYS What you frame is what you might get to see of what there was of what you thought you saw

California

Bear River Trestle

•

Donner Lake

•

Empire Mine

•

Grass Valley

•

San Francisco

•

Spenceville

•

Yuba River

•

Banner trails

Japan

Crusades

•

Cybernetics

•

Evacuation

•

Mt. Fuji

•

Growth

•

Higanbana

•

Isezakicho

•

Joy

•

Kinship

•

Lotus

•

Mob

•

Parfait

•

Road

•

Snow

•

Tanzawa

•

Thatching

View findingWYFIWYMGTSOWTWOWYTYSWhat you frame is what you might get to see of what there was of what you thought you sawFor reasons I can't remember, it fell to me to take possession of the family camera when we made our one and only trip back to Iowa in 1958 to meet who was left of my father's family there. It was a common Kodak box camera that used 120 roll film, which had become the standard of snapshot home photography. It was probably the same one my parents had used to take most of the family pictures up to that point. It was not my first time to use the camera. I had previously borrowed it to take pictures of some of my friends, who also took pictures of me with the camera. I also used it to take pictures of some girl friends. I have contemporary prints, and in many cases the negatives, of most of these early pictures, some in black-and-white, some in color. Baldamatic III bought my own first camera, the Baltamatic II I am using in the image to the right, by the summer of 1962, while working at San Francisco Naval Shipyards. One of the electrical engineers I assisted at Hunters Point, in a job created for engineering students, was an amateur photographer. Jim -- or "Mac" as he was also called, based on his family name, which unfortunately I have forgotten -- had prints of his work on the wall behind his desk. He had several cameras, including a 4x5 and a Hasselblad 6x6. For many years I dreamed of someday owning a Hasselblad. In the late 1970s I considered a number of made-in-Japan 6x6s, and was torn between Mamiya and Minolta models, but decided that I preferred the rectangular aspect ratio and the compactness of 35mm films and cameras, and so I bought my third and last single-lens-reflex Pentax. In the early 1960s, though, my interest in photography was limited to wanting only a quality camera that would let me control basic settings. There was also the matter of not having much money. Considering my needs and budget, Jim recommended the Balda, which had a range finder and decent lens, as a good 35mm entry model. Jim didn't pull the Balda out of a hat. I had mentioned it to him. And by coincidence he had one. I mentioned it because Wilton Vincent, an uncle of mine, actually an in-law 2nd cousin twice removed, had recently bought one. Wilton was the first to inspire my interest in 35mm cameras. He and Theo -- my mother's 1st cousin once removed, hence my 2nd cousin twice removed, who I knew as an aunt -- were our closest relatives geographically and socially. They liked to travel, and Wilton, a Methodist minister, swore by ratings in Consumer Reports for everything he bought, from straight-edge razors to cars. 35mm cameras, which had been around for a few decades, were just then breaking into the general consumer market. In those days, only people who took an interest in photography, and were willing to manually focus and measure the light, and fiddle with film and shutter speeds and F stops, bought them. But even in San Francisco, practically no photography shops had Baldamatics. Baldas were made in Germany, and my amateur eyes saw the Baldamatic as a poorman's Leica. Today I think of it as a 3-speed bicycle with training wheels compared to a 10-speeder. My earliest Baldamatic prints are dated 1962. At the time I took only color. I shot both negative film and transparancies, but mainly transparancies, until the late 1960s, when I abandoned positive film except for a couple of rolls I took in the late 1980s with my last Pentax. Pentax SpotmaticsI bought my first SLRs -- two identical Asahi Pentax Spotmatics -- in 1966 while serving in the U.S. Army as a laboratory technician in the 106th General Hospital at Kishine Barracks in Yokohama. One had a silver body, the other a black body. I continued to take transparancies with them, but I also began to shoot monochrome film, which was still very much the standard of artistic photography. I often carried both cameras, the silver body with a 50mm f/1.4 lens, the black body with a 135mm f/3.5 lens, my favorite for people shooting. Black and whiteSometimes I loaded both Spotmatics with color, other times one with color and the other with black and white. My interest in black-and-white was inspired by William Harvey, who was serving in the 106th as a radiology technician. Bill later went to medical school and became a diagnostic radiologist. He got a bit of heckling because his name is reminiscent of a famous anatomist. Bill honed his photography skills by developing and printing black-and-white film in a corner of the radiology lab. I still have most of the Pentax negatives and some of the enlargements Bill made in the radiology lab. Half a century later, scans of his prints are generally superior to scans of the negatives. New homes for the SpotmaticsDuring the summer of 1963, and up to the start of my military service that fall, I worked on a survey crew with the Tahoe National Forest in Nevada City. Christopher Wiegman, my party chief, taught me the practical skills that I hadn't learned in the surveying courses I took at Sierra College in the fall semester of my freshman year as an engineering major. I got only a C in the course, which reflected my boredom with it. In 1963, Kit and his family were living at his mother's home in Nevada City. By 1966, when I mustered out of the Army, they were living in a home he and his wife were still building just off Highway 49, also within walking distance of the Forest Service office, where during the winter he helped design roads using data collected during the summer. I had kept in touch with him, and he arranged for me to return to work with the Tahoe from early 1967. I worked on several crews, though mainly on his crew, until I returned to Berkeley that fall. When returning to school, I sold Kit one of my Spotmatics with 50mm, 28mm, and 135 lenses and a set of filters. I gave the other, with a 50mm lens and a Kenko Skylight filter, to my father. That left only a telephoto zoom lens, which I sold for slightly more than I paid for it, through a Market Street, San Francisco camera shop that accepted items on consignment. I had used the telephoto lens only once or twice and it was in like-new condition. The buyer was delighted by the price, which was substantially cheaper than an import. I myself had bought it at a substantial discount through the Navy Exchange in Yokohama, which was open to all U.S. military and government personnel and their dependants, and some U.S.-employed Japanese. The buyer, Kaare Myksvoll, was a civil engineer for the city. By coincidence he had graduated from the College of Engineering at Berkeley in the early 1960s about the time I was studying electrical engineering. He had immigrated to the United States from Norway and naturalized. He invited me to dinner one night, at his home in what is now called the Inner Sunset district, and his wife fell asleep while listening to us talk about photography. That was the only time I met him. Pentax MXI would not own another camera until 1978 or so, three years after returning to Japan in 1975, to begin what turned out to be a permanent stay -- so permanent that I am a Japanese national. I was about to be a father, and I toyed with the idea of buying a 6x6, but opted for the more familiar and, for my purposes, useful 35mm format. I thought of buying a Nikon, which of course ranked first on practically everyone's list of qualiaty through-the-lens cameras. But I ended up bying an Asahi Pentax MX, black body, with three lenses, a set of filters, and a few other accessories. I bought everything through a student at the English school where I taught a couple of days a week. He owned a small photography shop and gave me a substantial discount. I visited his shop only once and remember only that his name was Satō or possibly Saitō. It could well have been something else. Age has taken its toll on my memory. All of the hundreds of pictures I took of my children growing up -- of my daughter born in 1978, and of my son born in 1982 -- I took with the Pentax MX, which I still have. It lay unused for about a decade, during which the lenses were invaded by a fine filament mold -- a common syndrome of complex lenses. I had the lenses cleaned around 1990, which was not cheap, and continued to use the resuscitated Pentax until the late 1990s, when I bought the first of the three digital cameras I have thus far owned. For the past 17 years, the Pentax MX and all its accessories have sat in a box in my closet. Everything is clean, but alas some filament mold has reinvaded the lenses, and focusing has become difficult. Ten years ago I would have been dumb enough to attempt to clean the lenses myself, simply because tearing things apart and putting them back together appeals to me. But not now. Polaroid, Sony, Kodak, and CanonNone of my digital cameras have been anything near professional grade. The first digital camera I bought, in early 1998, was a Sony Mavica MVC-FD7 with a 10x optical zoom lens and a built-in 3.5 inch floppy disk drive for storing images. The resolution wasn't bad for close-up work and portraits but was horrible for group shots and scenery. And even the better images were too poor to be worth printing anything larger than a wallet-sized picture. Within just a few months, a number of better cameras came out, with higher resolutions and flash memory. And by the summer of 1998, barely half a year after I had bought the Sony, I had given it to some students in the photography club at the school where I taught a couple of days a week, and bought a Kodak DC260 Zoom. The Kodak would be my work horse until 2007, when it finally gave out, and I bought the 10 megapixel Canon PowerShot A640 I continue to use with satisfaction. I take mostly medium size shots that average a bit over 1 megabyte. They are satisfactory for up to A4 prints and website presentation. Professional photographers and high-end hobbyists will laugh at this history of camera possession, which includes, I forgot to mention, a brief flirtation, while in Berkeley and Japan in the early and mid 1970s, with a Polaroid SX-70. It never met my expectations, except for documenting before-and-after repairs and other matters at the apartment house I managed. Hence my return to the Pentax family in the late 1970s, after I had returned to Japan and had both the money and the incentive to buy a real camera. Photography contestI mustered out of the Army and returned to Grass Valley in the fall of 1966. Shortly before leaving Japan, I bought an issue of Asahi kamera (朝日カメラ), which had an advertisement for the magazines monthly photo competition. Before resuming my studies at Berkeley in the fall of 1967, I entered a color photograph I had taken in a park near Kishine of two children being treated to sweets by their grandmother. This is the only work I have ever entered in a contest. Though it didn't place, it remains my favorite attempt to capture a moment of totally spontaneous and innocent delight -- and I have titled it simply Joy (see below). As of 2015, both Kit, who I last saw in a Glenbrook, Grass Valley parking lot in 2011, just long enough to say hello to -- and Kaare, who I never saw again after the dinner at his home -- were living at the same addresses they were when I sold them the camera equipment. In the nearly half century interval, I have lived at 8 different addresses, including 1 in Grass Valley, 2 in Berkeley, and 5 in Japan including 1 in Urano, 1 in Tokyo, 1 in Nagareyama, and 2 in Abiko. Karel van WolferenIn the late 1960s, in the office of George De Vos, an anthropology professor at Berkeley, I met a young Dutch journalist and photographer by the name of Karel van Wolferen. He would later be one of my best friends. Some people know him as one of the world's finest journalists. Fewer people know that he is also one of its finest photographers. Our friendship began in the late 1970s after I had returned to Japan to write my doctoral dissertation. I had opportunities to witness his photoshooting with all manner of cameras, but most significantly an 8x10, which at times I helped him lug around and set up in the countryside somewhere in Japan. Karel, at his various residences in Japan in those days, had a lab for printing and enlarging his photos. Today he works with the highest quality digital cameras and elaborate software that allows him to compensate for all manner of distortions introduced by even the highest quality cameras and lenses. He also writes some of the most interesting and insightful evaluations of vintage lenses adapted to digital cameras, and critiques of contemporary trends that he finds to be what I would call anti-photographic. Exhibits of his work have been mounted in China, Japan, America, and Europe. Nothing compares with seeing actual prints of his work, but representations in his The.me articles amply show the range of his aristry. I have gotten into arguments with Karel about composition, for which I believe there to be "rules". This is not to say that I understand them, or his version of them. Karel, however, adamantly denies that there are "rules". I counter that to speak of "rules" in the same breath that one speaks of "art" is not a contradiction. To the extent that "art" is structured, all art conforms to rules. The rules of art, I would argue, are not so sacroscant that they should never be broken, but the art of rule-breaking is to know when, and how, to break a rule. And an artist, like a criminal, has to take responsibility for breaking rules, even self-made rules. Karel has generally followed certain rules since his earliest black-and-white studies of life in Japan in the 1960s. I would even aver that at times he makes the rules exemplified in his work -- for that is exactly what artists do. Post-processingIn the 1960s I sometimes bought Popular Photography, from which I gradually learned the relationships between settings and films, the effects of filters, and the significance of depth of field -- but most importantly, for me, the difference between a casual snapshot and a consciuosly composed picture. My earlier pictures show an obsession with composition that at times compromised concerns I should have had with the subject matter or lighting. I am of what I call the WYFIWYMGTSOWTWOWYTYS school -- meaning "What you frame is what you might get to see of what there was of what you thought you saw". In other words, I am willing to live with what I get with nothing but the camera and the choices I make when looking through the view finder and snapping a picture. Today I would put subject matter, composition, and illumination on the same level of importance. The art of photography is to get them all "right" at the same time. I am willing to crop a better composition from a picture that in hindsight includes more than I think it should, and occasionally I have done this. I have also, as when designing a book cover for a friend, cloned out a few details around the main subject of a photograph. And sometimes, though rarely, I have rotated an image to improve its alignment. But you can't add anything you missed. You either get it or you don't. In principle, I do not engage in other forms postediting. I leave colors to the quality of the film and the paper or the scanner. I don't fix red eyes or doctor hot spots. When scanning old negatives and prints, I remove surface dust but leave scratches and folds, and don't compensate for fading or discoloration. On a few scans of old black-and-white shots, I have covered conspicuous white blotches with patches copied from adjacent areas. William Wetherall |

California

While I settled in Japan and became a Japanese national, I am not -- as some people may think -- a world traveler. I am more like a bear that pretty much stays in his valley, on his side of the river and ridge, and doesn't wander too far either upstream or downstream.

The Wetherall family, which originated in San Francisco in the late 1930s and early 1940s, lived mainly in the Sunset District, and spent a lot of time in Golden Gate Park. We took day trips to picnic, hike, or swim, at places like Mount Tamalpais and Santa Rosa north across the Golden Gate Bridge, and San Mateo, Palo Alto, Santa Cruz, and Carmel south of the city. Summer vacations were spent camping in redwood forests on the Eel River along the coast north of San Francisco and at Big Basin near the coast to the south. Once we ventured as far inland as the Dardanelles in the Sierras to the east.

Our move to Grass Valley in 1955 ended such day trips and summer vacations, partly because my father became very busy, but mostly because Grass Valley was in the mountains. We practically lived in the woods. Our home was part of a development that was carved out of the woods, and we were a 2-minute walk -- a minute if you jogged -- from the entrance to woods that are now part of the Empire Mine State Park. Our lot included a dozen very large cedars and pines that were left on the property when the house was built. My brother and I could, and did, walk through the woods to get to school.

Northern California

When I say we considered California our "home" I do not mean the entire state. When I was growing up, there was serious talk about splitting the state in two -- north and south. The north had water. The south needed water.The north had build many dams, partly for flood control, and partly to provide water to the south. The population of the south had grown to the point that significantly out-numbered the north, and this translated into political influence in Sacramento, which was just about where the state might be divided.

Northern secessionists didn't get their way, of course. But many northerners are proud not to be part of the madness they see in the tangle of freeways connect Los Angeles with the municipalities that sprawl around it and created -- when I was growing up -- southern California's world-famous smog. Similar problems affected the Bay Area centring on San Francisco, and the Sacramento area, but no where to the extent they came to practically define the south.

I have joked that Northern California is between the United States and Japan -- an independent state that trades water for Hollywood films. Dividing the state wouldn't be anything new. When the area was under Spanish rule, the Provincia de las Californias (Province of the Californias) consisted of Alta (upper) and Baja (lower) California. Spain's defeat by the United States in the Mexican-American war of 1846-1848 was settled by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, in which Spain ceded itsforced onto the remnant Mexican government, ended the war and specified its major consequence, the Mexican Cession of the northern territories of Alta California and Santa Fe de Nuevo Mexico to the as a province of Spain

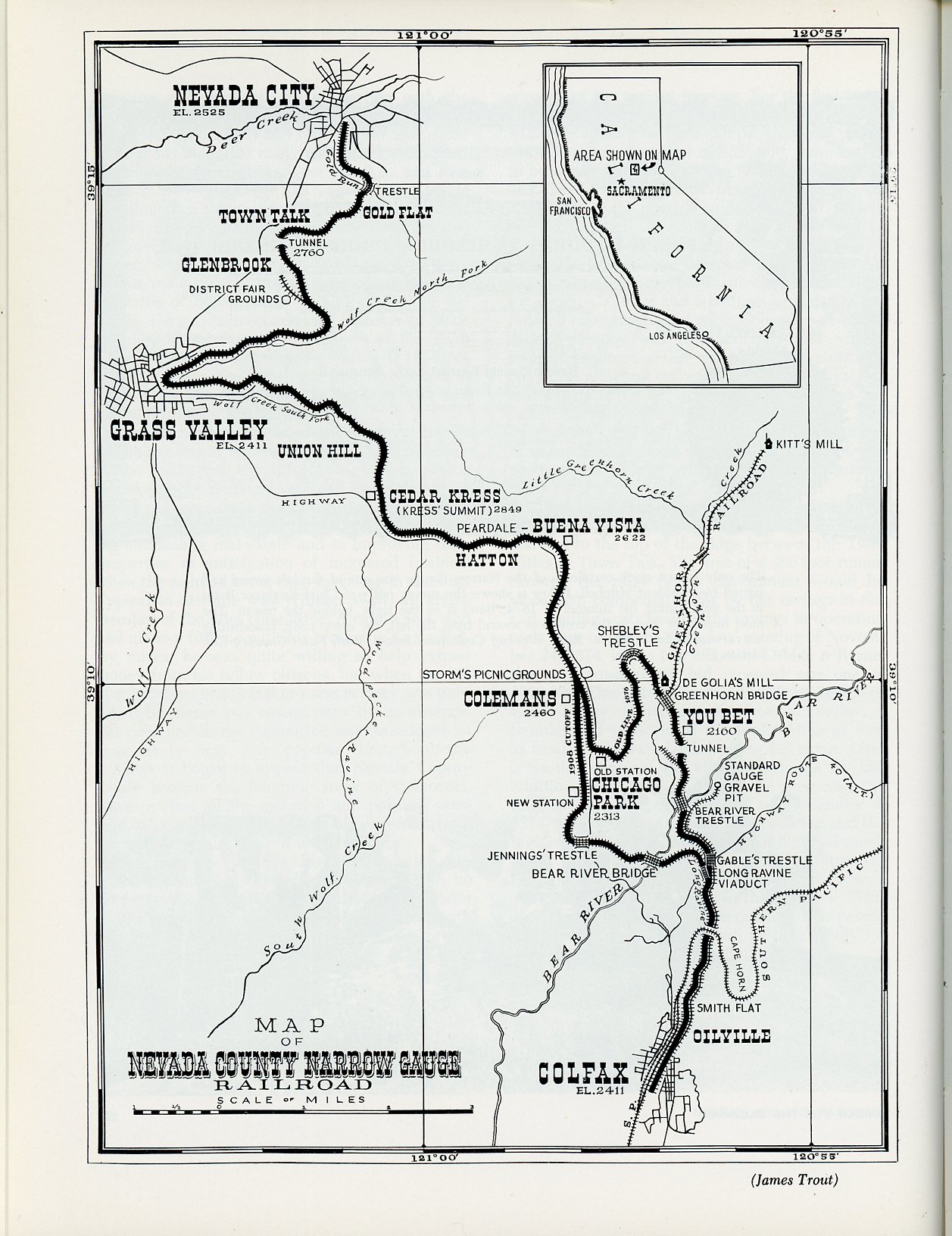

Nevada County Narrow Gauge RailroadThe Nevada County Narrow Gauge Railroad (NCNGRR) operated between Colfax in Placer County, and Grass Valley and Nevada City in Nevada County, from 1874 to 1942. It was nicknamed "Never Come, Never Go" (punning NCNG) on account of its sometimes unpredictable operations. One account relates the frustrations of a woman who boarded a mixed train in Colfax for Nevada City. Mixed trains carried passengers and freight, hence stopped not only for passengers to board and deboard, but to load and offload frieght and pickup or drop off rolling stock. When finally the train reached Town Talk, between Grass Valley and Nevada City, the woman plead with the conductor to hurry the train, as she was going to have a baby. The conductor told her she shouldn't have boarded the train in such a condition. The woman said she wasn't in that condition when she boarded. (Wyckoff 1986, page 45) Colfax was a station on the Central Pacific Railroad, later Central Pacific Railway, a standard gauge line that plied between the San Francisco Bay Area and Sacramento in California, and Salt Lake City and Ogden in Utah. Practically all of the line ran through Nevada County, and was built to connect Grass Valley and Nevada City with the transcontinental main line. The principal developers and original owners of NCNGRR were gold mine operators. Timber interests, and communities along the proposed route, also coveted rail access to the Central Pacific trunk line at Colfax as well as to Grass Valley and Nevada City. Chronology1846-1848 Mexican-American War, during which the United States takes the Mexican territory of Alta California. Sets stage for the colonization of what would become the American states of California (31st, 1850), Nevada (36th, 1864), and Utah (45th, 1896), and parts of Colorado (38th, 1876), Wyoming (44th, 1890), New Mexico (47th, 1912), and Arizona (48th, 1912). 24 January 1848 Gold discovered in the vicinity of Coloma, a settlement along the South Fork of the American River in what became El Dorado County, county seat Placerville -- south of Placer County. Name derives from Cullumah ( Culloma, Koloma) -- the Nisenan name of the valley and a village on the river. 1849 Gold miners settle in camp they called Nevada on Deer Creek in 1849. First mine and sawmill built on creek in 1850. Nevada became county seat of newly formed Nevada County in 1851 and was incorporated on 19 April 1856. The name of the town was officially changed to Nevada City in 1864 when Nevada Territory, created from Utah Territory in 1861, became the 36th state in 1864. 1850 Gold discovered on Gold Hill in a settlement near Nevada known as Boston Ravine and then Centerville. Gold also discovered at nearby Ophir Hill, which became part of the Empire Mine in 1854. The post office established in the settlement in 1851 was called Grass Valley, and this became the name of the town when it incorporated in 1860. 9 September 1850 California becomes the 31st state of the Union. Its statehood was expedited to secure a federal foothold in what was then America's most rapidly colonializing territory, thanks to the gold rush. 1851 Nevada County county formed from part of the original Yuba County, parts of which also formed Placer and Sierra Counties. The County seat was Nevada, which was renamed Nevada City in 1864. Most of the territory that makes up the foothill counties that originally defined Yuba County was inhabited by, and belonged to, a tribe whose descendants stylize themselves as Nisenan. Such people are thought to have lived in the territory for about 10,000 years. Nisenan descendants refute the popular association of the tribe with Maidu, digger, or Southern Maidu people, although some sources equate Nisenan with the Southern Maidu who inhabited the American, Bear, and Yuba River watersheds, and proximal parts of the central valley. 1861-1865 The War of the Rebellion, in Union legalese, until the early 20th century, when "the Civil War" came into widespread use. The United States of America fought against the Confederate States of America for a number of reasons, including the desire to end slavery, but mainly to bring the succeeded slave states back into the Union. 1861The Central Pacific Railroad was incorporated in Sacramento on 28 June 1861. Its route was authorized in Washington, D.C. on 1 July 1862, a ground breaking ceremony was held in Sacramento on 8 January 1863, and freight and passenger trains began plying between Sacramento and Newcastle in June 1964 -- all during the War of the Rebellion. The Central Pacific was built with large numbers of Chinese laborers, who quickly made up more than half the labor force. The tracks and tunnels over the Sierras at Donner Pass were completed in 1867. Passenger service over the Sierras from Sacramento to Lake's Crossing, now Reno, began in 1868. Construction of the Union Pacific Railroad broke ground in Omaha, Nebraska, on 2 December 1863. Central Pacific and Union Pacific tracks were joined at Promontory in Utah on 10 May 1869, thus completing the 1st transcontinental railway in North America. 5 days later, the 1st transcontinental train reached Sacramento. By the end of the year, Central Pacific was serving Oakland Terminal at San Francisco Bay, where it made connections with Western Pacific. Central Pacific and Western Pacific, and several other westcoast lines, were consolidated in 1870. The Southern Pacific Railroad leased Central Pacific Railroad in 1885, rebranded it Central Pacific Railway (CPR) in 1889, and merged it into Southern Pacific in 1959. The Union Pacific bought Southern Pacific in 1996. 28 October 1864 The Union newspaper founded in Grass Valley. Later issues carried the motto "Founded in 1864 to Preserve The Union . . . One and Inseparable". Though no longer published on Mill Street in Grass Valley, and no longer locally owned, the paper continues to be read mainly by residents of Nevada County centering on Grass Valley and Nevada City. 1867 The United States purchases Alaska from Russia. Alaska incorporated as a territory on 24 August 1912. 20 March 1874 Colfax to Grass Valley and Nevada City railway route approved by California government. 4 April 1874 Nevada County Narrow Gauge Railroad incorporated with headquarters in Grass Valley. 20 June 1874 U.S. Congress grants NCNGRR rights of way through public lands. January 1875 Construction begins. 11 April 1876 First train from Colfax reaches Grass Valley. 20 May 1876 First train reaches Nevada City. 25 August 1896 Original wooden trestle over Bear River, which marked the boundary between Placer and Nevada counties, partly burns, disrupting service until a section of the Howe Truss was rebuilt with a stronger design. 1898 Spanish-American War in spring and summer results in the United States acquiring The Philippines, Guam, and Puerto Rico, among other Spanish territories. During the summer, the United States annexes the Kingdom of Hawaii, which becomes the Territory of Hawaii on 30 April 1900. 1 September 1907 Ground broken for construction of new steel bridge over Bear River on new cut-off. The bridge was designed to handle a standard gauge track in the event NCNGRR decided to add a 3rd rail (Wyckoff 1986, page 62). The cut-off bypassed the northern swing up Greenhorn Greek, from where it spilled into the Bear River to You Bet -- then north across the creek, and back south and west to Chicago Park -- in favor of a shorter direct route west and north to Chicago Park. The cut-off required relocating the Chicago Park station. It also required a steel bridge about 1 mile downstream of the wooden trestle that crossed Bear River to Greenhorn Creek. The new bridge became the highest railway bridge in California at the time. 8 November 1908 Trains run people from Nevada City and Grass Valley, and Colfax, to see the completion of the new bridge (Wyckoff 1986, page 62). 1912 The territories of New Mexico and Arizona become the 47th and 48th states of the United States, completing the Union's "sea to shining sea" contiguous empire. 1938 Passenger service on NCNGRR discontinued. By the time the cut-off was built in 1907-1908, some people in Nevada County had automobiles. By the 1930s, automobiles had become the most common mode of transportation, and busses and trucks had also eaten into NCNGRR's passenger and freight services. 29 May 1942 Last commercial train runs as area gold mines were closed during World War II. NCNGRR began selling off and scraping its assets -- locomotives, rolling stock, tracks, machinery, and facilities. Gold was not an essential metal for military purposes. Incentives were offered men who worked in mines producing essential metals, and younger men were enlisting or being drafted, all of which caused severe labor shortages in gold mines. 25 July 1942 Last trip organized by employees, for employees, in defiance of orders not to have a celebratory trip because passenger service insurance had been canceled. Bob Paine gives an account of the trip in his memoirs as published in Robert M. Wyckoff's Never Come, Never Go! (pages 46-47). 1945 The Empire Mine reopened in 1945. But most other gold mines remained closed because they had filled with water or otherwise became inoperable due to lack of hands or funds to maintain them. 1956 The Empire Mine closes because the price of gold did not sustain production costs and demands for higher wages. The Empire closed a year after the Wetherall family moved from San Francisco to a home at the top of Silver Way in Grandview Terrace, directly across Colfax Highway from the main headframes of the Empire Mine, between Grass Valley and Union Hill. I walked to school in Union Hill through woods owned by the mine, and I swam in the pool behind the Bourn Mansion through a friendship with a classmate, Susan Bechaud, whose father -- a neighbor -- was a minerologist at the mine. The mansion, and the woods I walked through, are now part of the Empire Mine State Historic Park. 1959 Alaska becomes the 49th state on 3 January and Hawaii becomes the 50th state on 21 August. The 48-star flag was still official when I graduated from Nevada Union Senior High School in Grass Valley with the class of 1959 on 12 June 1959. The 49-star flag became official on 4 July 1959, and the 50-star flag first officially flew on 4 July 1960. Friday, 23 August 1963 An attempt to demolish the Bear River Bridge with dynamite breaks its back and one section falls. But most of the bridge is left hanging over the river. Monday, 26 August 1963 A second attempt succeeds in toppling the entire bridge. 1964-1975 American Vietnam War. |

||||||||||||||

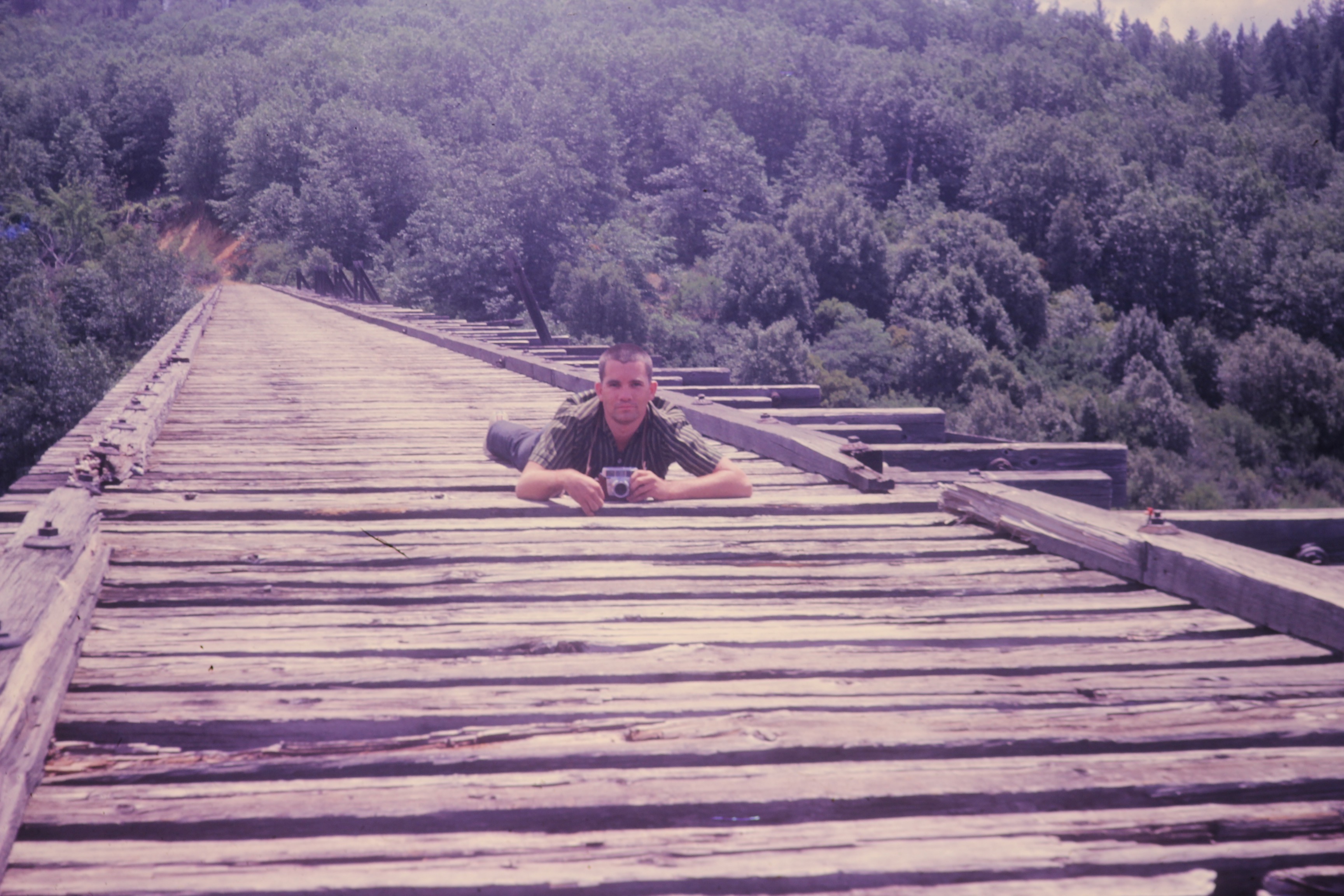

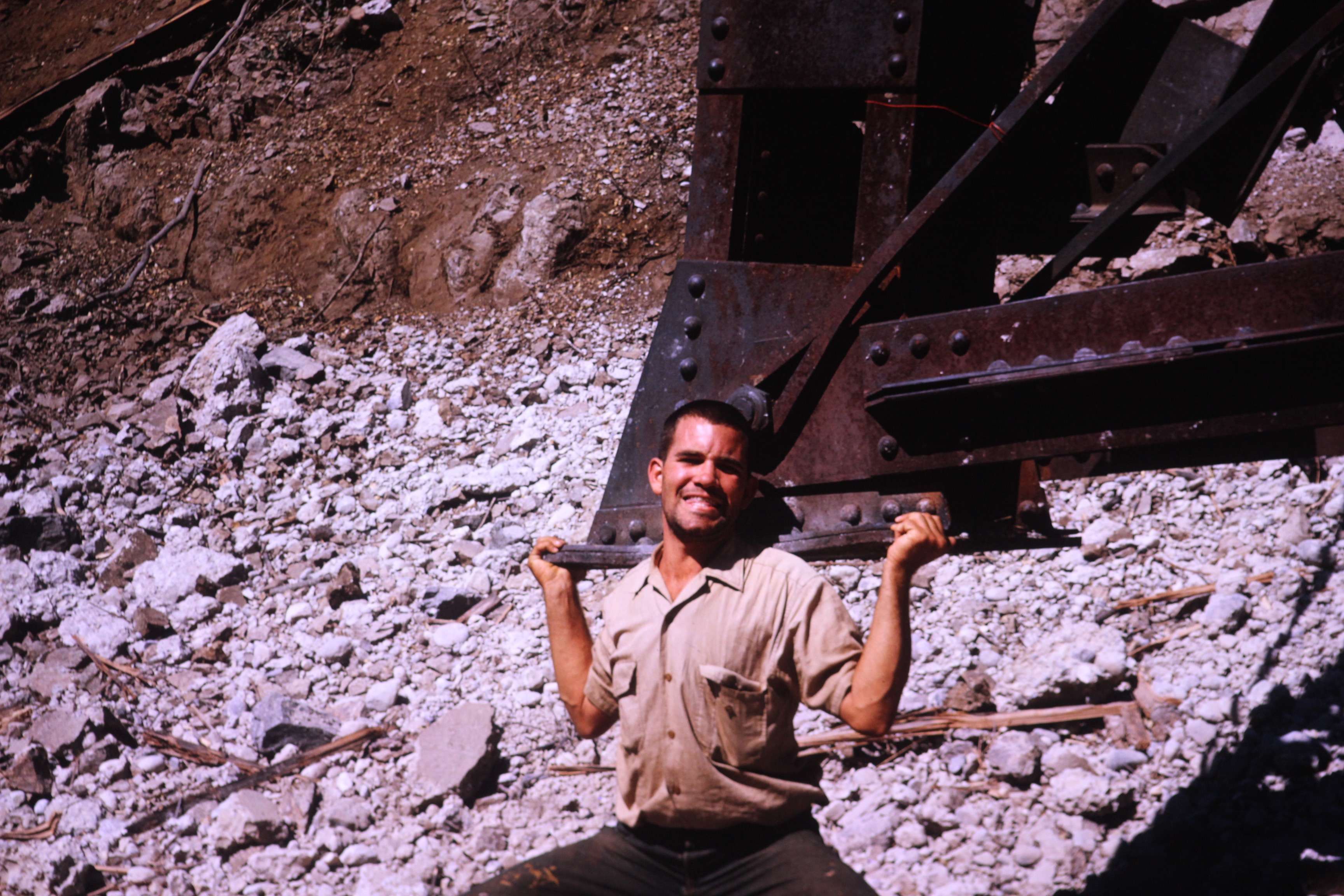

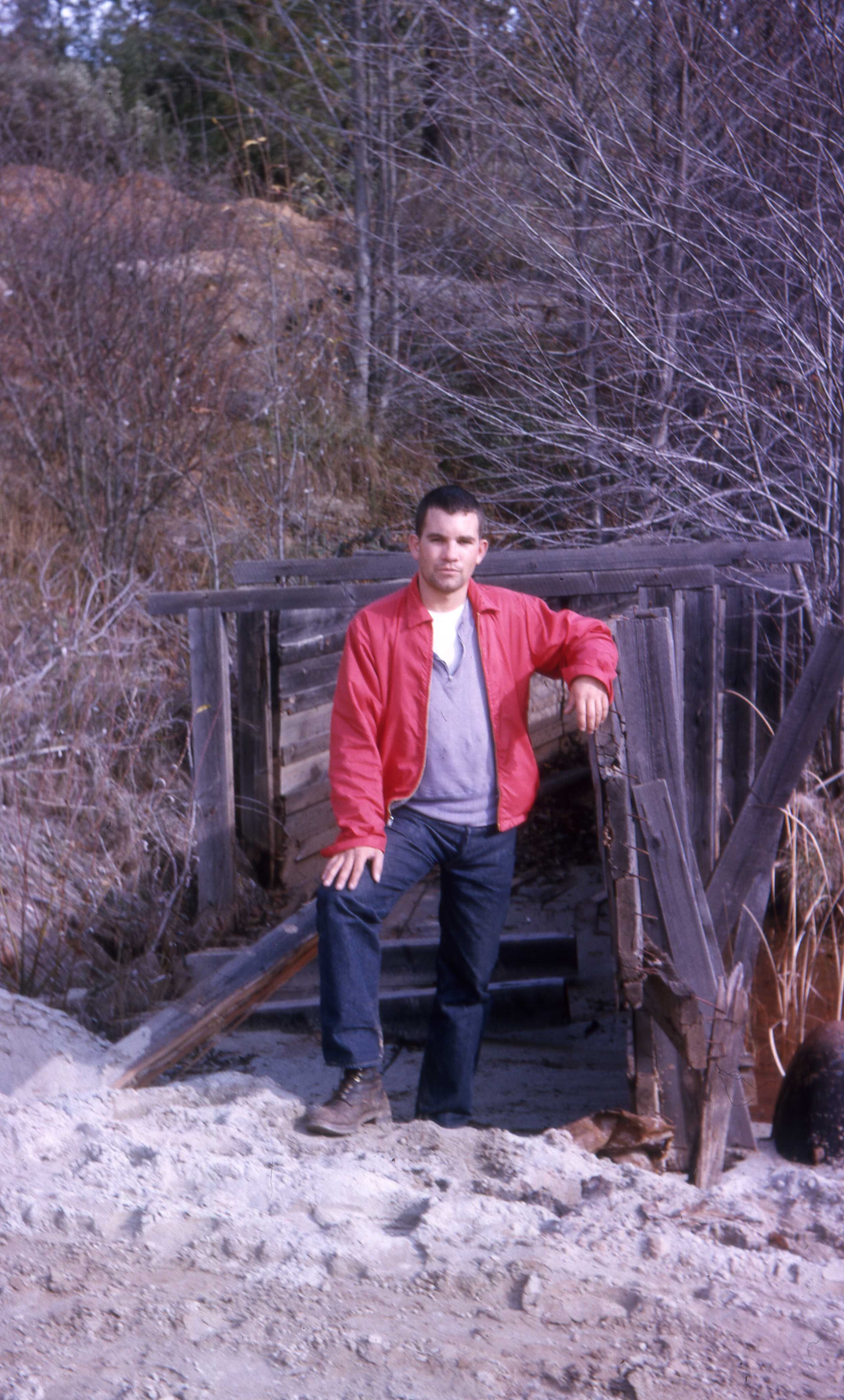

1963 photographs of Bear River Bridge before and after its demolition

Click on photo to enlarge ClassmatesAll the photographs on this panel were taken by Bob Lobecker on the occasion of 2 expeditions to the NCNGRR Bear River Bridge shortly before and after its demotion in late August 1963. Bob and I were classmates at Nevada Union High School in Grass Valley (Class of 1959) and at Sierra College in Auburn (Class of 1961), with John Phelan, a mutual NUHS and SC classmate and friend. The 3 of us had majored in pre-engineering at Sierra and passed the entrance exam of the College of Engineering at the Univerisity of California at Berkeley to enter the Department of Electrical Engineering from our junior year in the fall of 1961. Bob and John began at Cal as planned but I obtained a 1-year leave of absence to work another year in the Electronics Division at San Francisco Naval Shipyard (Hunters Point), where John and I had worked summers as engineering aids. Bob had worked summers on survey crews for the Tahoe National Forest headquartered in Nevada City. I began my junior year at Cal from the fall of 1962 a year behind Bob and John. By the summer of 1963, John had graduated and begun working for Pacific Telephone, Bob had to complete some course work so was still living in Berkeley, and I was working on a survey crew with the Tahoe National Forest, which preferred to hire local boys and was not then required to recruit summer help from the cities -- unlike when I worked for forest service in the late 1960s. Bob would sometimes come home on weekends to hike and prowl around old mines with me and a couple of my survey party work mates, Rene Barker and Dan Le Du. Rene was the sole graduate of Alleghany High School in 1962 and had started studying geology at a state college. His family still lived in Alleghany, between the Middle Fork and North Fork of the Yuba River, north of Grass Valley and Nevada City. His father was a geologist for the Sixteen-to-One Mine and also taught school in Alleghany. Dan Le Du, who lived in Grass Valley with his parents, had just graduated from NUHS in my sister's class, and planned to study engineering at Sierra and then Cal. His father had worked in local gold mines. See Donner Lake below. While at Cal, I had weathered the Cuban Missile Crisis in October and November 1962, but by the spring of 1963 I'd become so politically alienated by the prospects of working in the defense industry that I began auditing humanities courses and sat out my engineering finals. I was placed on academic probation for a year and decided to work for the forest service until I could figure out what to study. At the time Bob and I visited the railway bridge at Bear River, I was in the process of being drafted and faced the prospects of being assigned to a missile battery for 2 years. The following month, I enlisted for 3 years, which allowed me to chose my army occupation. I became a medic and ambulance driver and ended up a hospital laboratory technician. |

|

|

Bear River Narrow Gauge Railroad Bridge

|

||

|

|

|

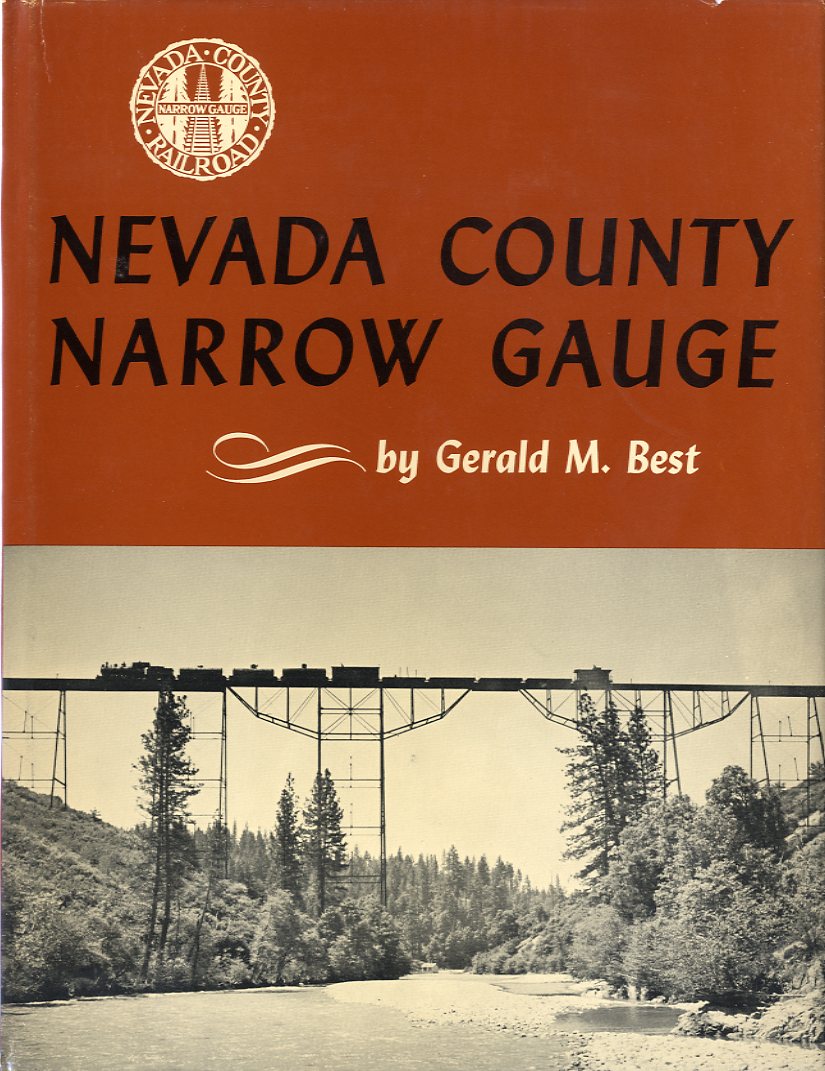

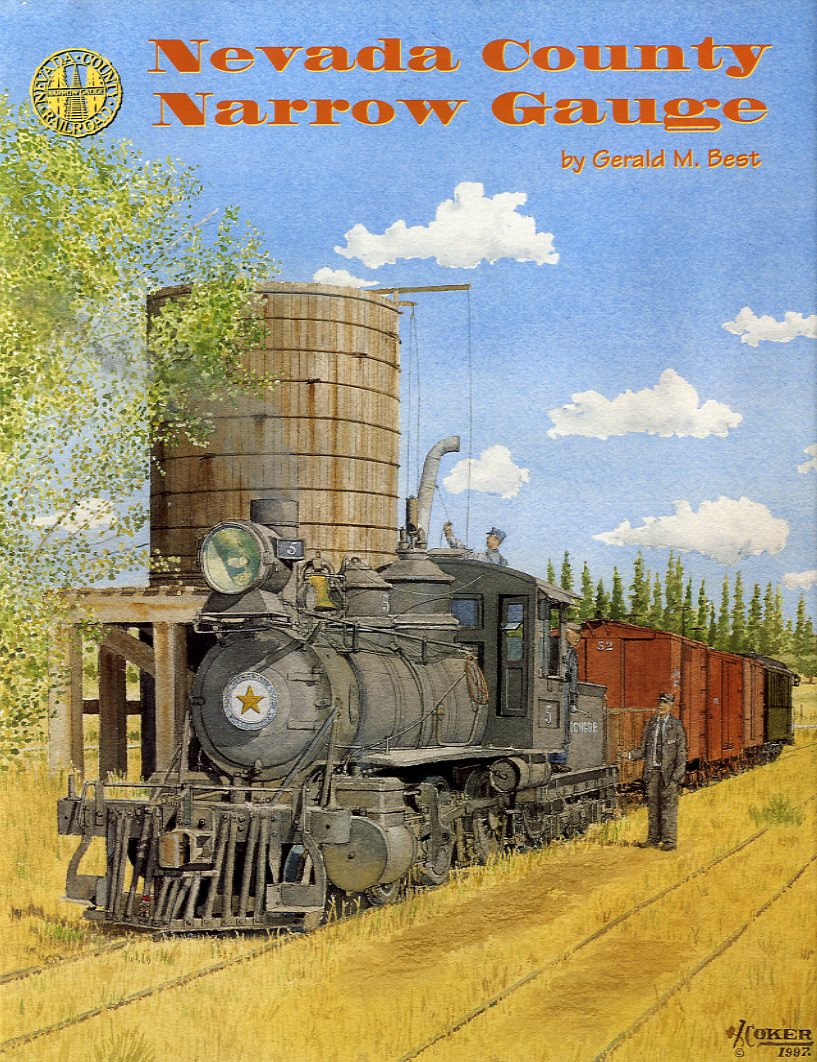

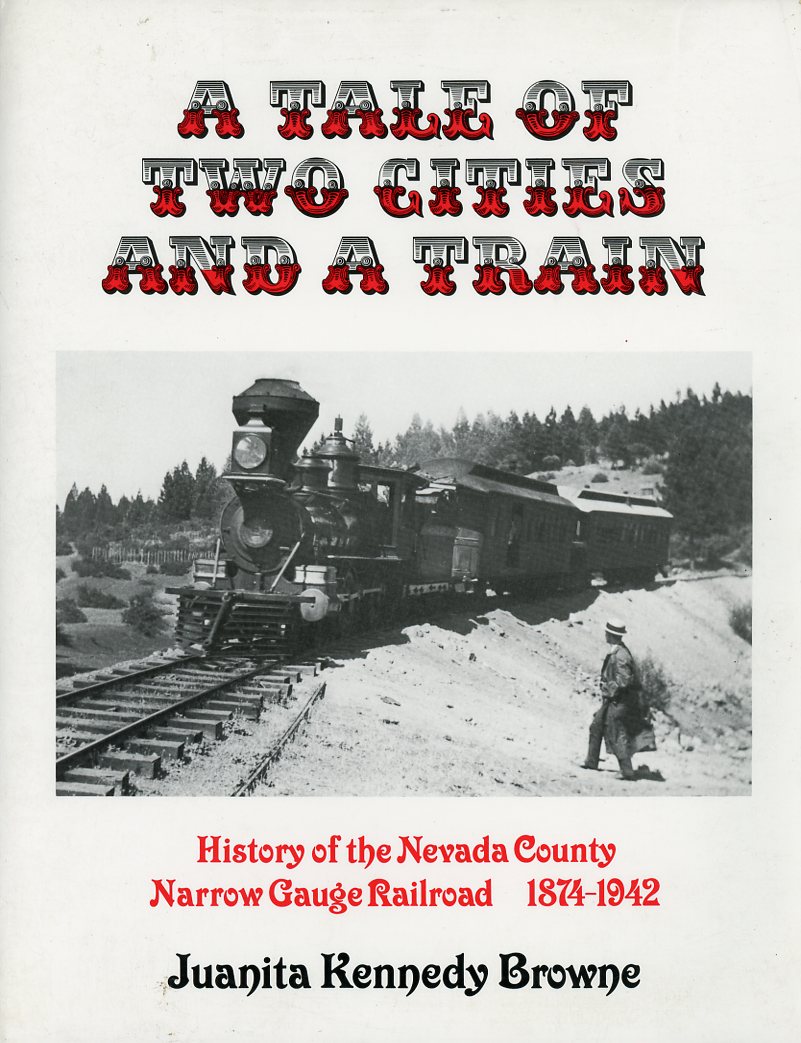

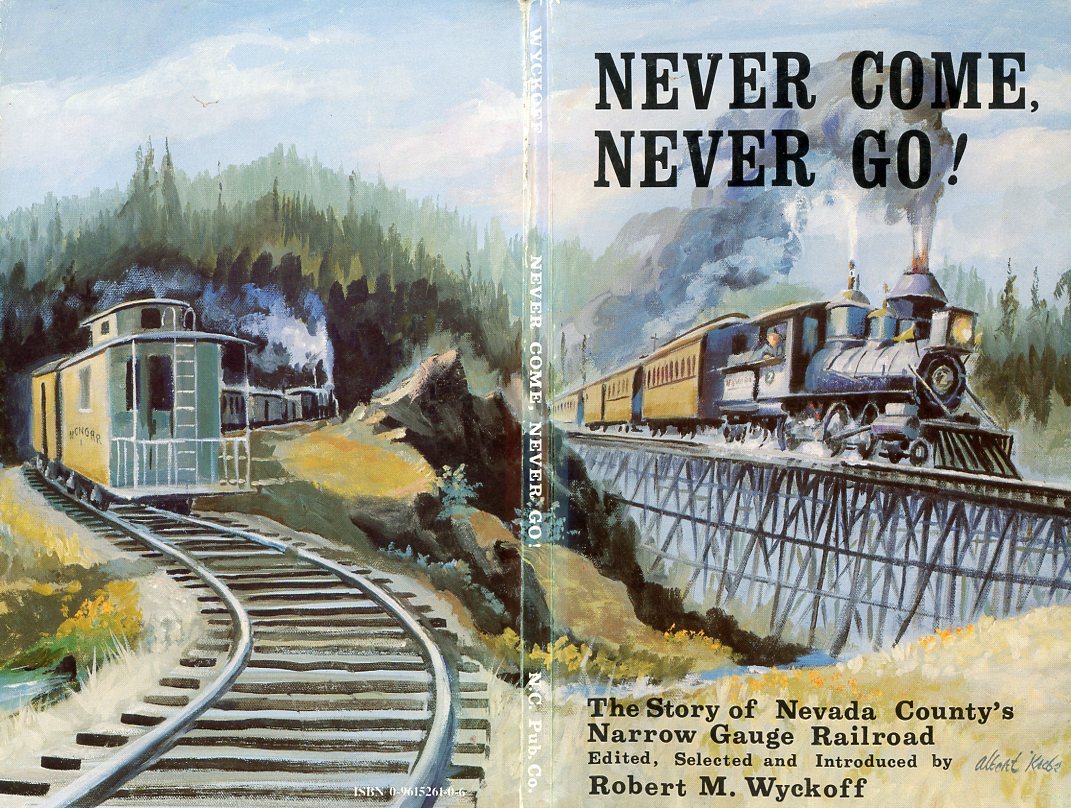

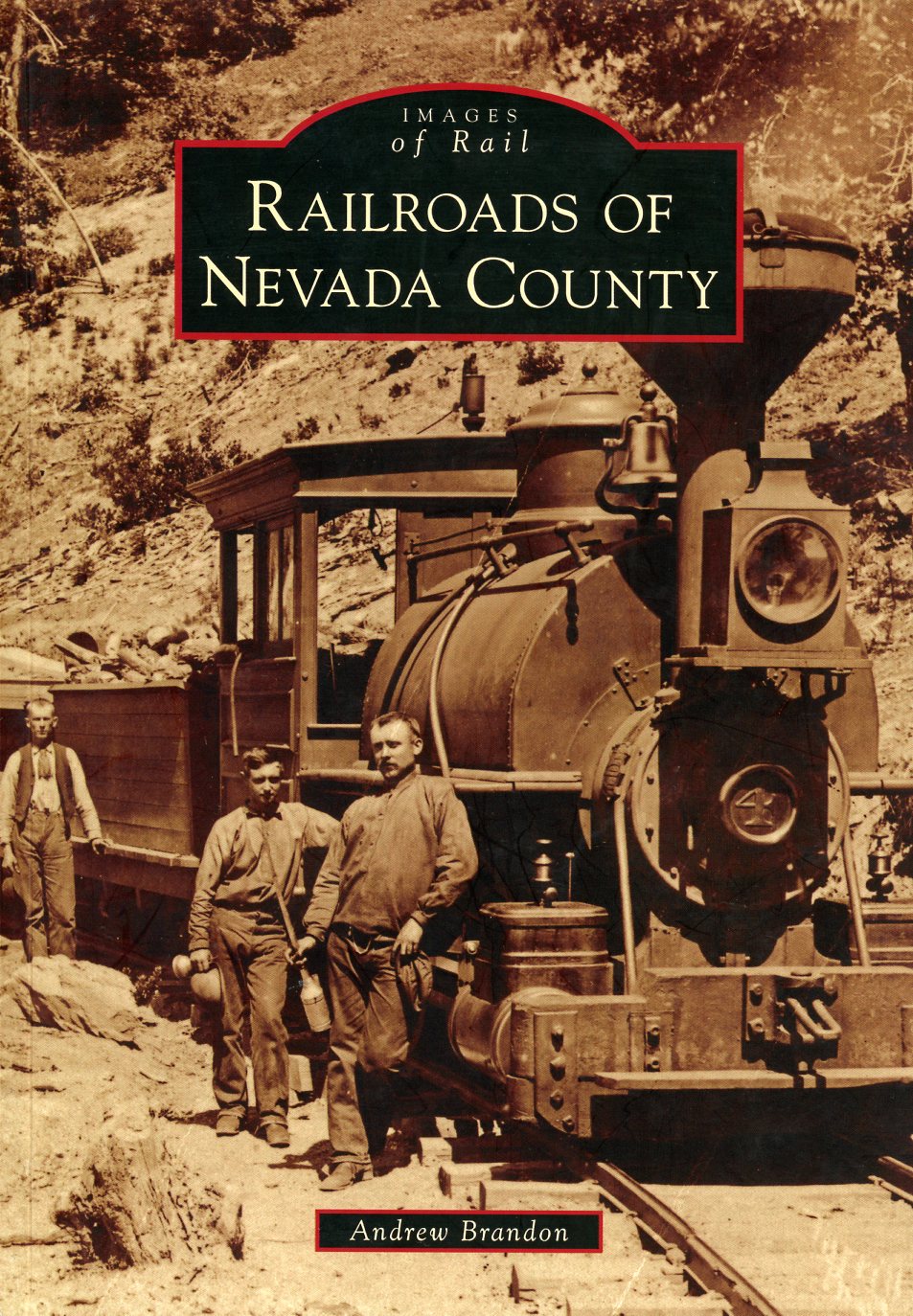

Books on Nevada County Narrow Gauge Railroad

Empire mineThe entrance to the Empire Mine was about a 10-minute walk from my home on the corner of Silver Way and Copper Avenue on Grand View Terrace north of Colfax Highway. The mine was just south of the highway, known today as State Route 174, which runs between Grass Valley and Colfax. Before it's closure in 1942, the Nevada County Narrow Gauge Raidroad ran between Colfax and Nevada City, via Grass Valley (see above). I was home for Christmas and New Year's on military leave, between basic training at Ft. Ord near Monterey, California, and medical corpsman training at Ft. Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas. I had an impulse to shoot some pictures around the mine, and went hiking by myself with my Baldamatic II and a tripod a day or two before I board a Greyhound bus in Grass Valley and made my way to San Antonio on Greyhound busses out of Sacramento and Los Angeles. The Empire Mine ceased operation during a labor strike in 1956. Operations were officially terminated in 1957, and post-closure work was completed in 1961. After this, there was virtually no one on the premises. The State of California did not purpose the mine property for the purpose of creating the present Empire Mine State Park until 1974. In the winter of 1963, the usual "No Trespassing" signs were evident, but there was no security. There was a caretaker, but I didn't see him, and if he was there, he either didn't see me or ignored me. For I simply walked through the front yard of the mine, by the head frames, all manner of rusty machinery, and the stamp mill and cyanide plant, into the area in the back where the tailings from the cyanide plant filed a dammed ravine. I had played around the area before. There was small a pond, and the remnants of a wooden canal with a water gate, through which water could be flowed into the sprawling lake of tailings. The tailings had the appearance and consistency of a gray sandy clay. Rain water would collect on the surface, but it would quickly evaporate, and you could walk across the dunes. across which one could walk when rain water before. there area in the back where the dregs of the cyanide and mercury processing were dumped in what had INVESTIGATEcyanide and mercury processing diverted into unlined tailing ponds mine’s toxic waste legacy. Sand Dam area near the mine’s former cyanide plant, which has tailings with unsafe concentrations of mercury, cyanide and arsenic. e need to close it off to make sure kids don’t get in the sediment,” movements to privatize the park in order to pay for the continuing clean-up operation opposition to corporate control, which would separate the toxic legacy problem from history, which needs to protected from coporate and even state interests that would reduce the historical attraction of the park, which is a major tourist draw for the local community. Additionally, samples taken from the Magenta Drain ? a major channel designed to funnel water from the Empire Mine’s 370 miles of tunnels into nearby Little Wolf Creek ? showed concentrations of arsenic approximately 40 times greater than acceptable state and federal safety levels. The Magenta Drain continues to discharge water from the mine into the creek to this day, the complaint said. Dam built in XXXX after the city of Grass Valley passed an ordinance prohibitting the mind from allowing its waste water to flow into Wolf Creek, which runs through the city. Little Wolf Creek runs close to the mine and into |

Grass ValleyForthcoming |

San FranciscoForthcoming |

SpencevilleForthcoming |

Yuba RiverForthcoming |

Banner trailsForthcoming |

Japan

Forthcoming

Crusades (Kishine, Yokohama, 1966Everyone else took pictures of the chapel out of view to the left of the cross. Or of the chapel with the cross. I took pictures of the cross with the ammunition magazine. The chapel was the most prominent building at Kishine Barracks, where it contrasted with the boxy ferro-concrete buildings that had been built shortly after the Korean War as quarters at what was then a rest and recreation facility. I was a member of the 106th General Hospital that arrived in late December 1965 to convert the base to a full-service medical facility with an initial capacity of 600 beds. By mid-January we were receiving wounded soldiers from Vietnam. I was a laboratory technician in the Pathology Service, which was responsible for all clinical tests involving blood, urine, feces, sputum, pus, semen, spinal and other fluids, tissue from biopsies and autopsies, and blood banking. The U.S. Army is supposed to be non-denominational, but almost all military bases of any size have a non-sectarian Christian chapel. Like other such edifices, perhaps to be that much closer to heaven, the chapel at Kishine sat on the top of a rise toward the north side of the base. It also had its own parking lot, presumably to accommodate worshippers who lived off-base and drove. I took several shots, some of which had better backgrounds than this one but at the expense of putting the "Ammunition Storage" sign too far in the distance. I thought of shooting the sign with the cross in the background, but I wanted to include at least part of the fairly large hill of the neighborhood to the east of the base. I also wanted the perspective created by the cross and the fence along the north boundary of the base. Weapons and crosses are inseparable in the American military, which defends "one nation under God" with a Protestant more than Catholic, and Christian more than Jewish spirit. We had a Jewish chaplain at Kishine, but as I recall there were no representatives of Buddhist, Hindu, Shinto, or other pagan spirits. My faith, or rather my lack of faith, would not have mattered to the unit chaplain, though. He was obliged to come to even my death bed in an attempt to qualify my agnostic ass for heaven. If he were to ask whether I'd made peace with "your God" I wouldn't tell him to go to hell. I'd look him in the eye, as I imagine Thoreau did to whomever is supposed to have asked him this question, and tell him I'd never quarreled with "my God" as the Army preferred to phrase it. The problem is, I couldn't even be sure I had a God -- but if I did, and if I had met him, her, or it, I could not have stopped myself from quarreling with the person or thing -- not because I'm a quarrelsome person, mind you, but simply because I can't resist playing Devil's Advocate. In basic training we had regular sessions called "Chaplain's Hour" at which trainees were urged to be spiritual. We were reminded that "faith" was an important if not essential source of a soldier's loyalty and fighting spirit. This notion was even embedded in the Code of Conduct that we were required to memorize in boot camp. The code began and ended with these numbered paragraphs.

The highlighted phrase suggests that "God" came before "country" and that the "country" was subordinate to "God" to the extent that soldiers were expected to "trust" both. The "my" was supposed to make it seem as though there was room for a personal God, as opposed to a collective or shared one-and-only God. I can hear someone say, "Find your OWN God, dude! That's MINE you're praying to" as he waves a hand toward an armory and ammunition dump. If I had to brainwashed to resist brainwashing, I would have preferred the "whatever gods that be" as in William Ernest Henley's "Invictus", sung in the voice of a man whose "head is bloody but unbowed" thanks to the gods who gave him an "unconquerable soul". I remain an agnostic. I take many thoughts to bed with me, and don't easily fall asleep. I'm not dyslexic, but living in Japan as long as I have, I've gotten used to reading some Japanese expressions from right to left, even bottom up, and this sometimes effect my thinking in English. At times I lie awake all night wondering if there really is a dog. The morning, noon, and evening news assures me that the Crusades are alive and well. The armies of the gods that be are patrolling their sacred territories, sniffing even the posts of the fences of coveted territories. Coveting thy neighbor's wife is disallowed, but hungering for market share and power, in the name of the state or stock holders, appears to be sanctioned by the dogs that be. The next World War may well begin with a dogfight. |

Cybernetics (Hakusan, Abiko, 2014)I would like to have captured the entire shovel on the cherry picker to the right but I couldn't. I was standing on a ledge of dirt 30-centimeters wide, with my back flush against the cinder block wall on the property line behind me. Had the ledge caved in, or if my 26-centimeter shoes had slipped, I would have slid to the bottom of the 2-meter-deep hole, which was 3-meters across, between me and the cherry picker. The machine was parked over the weekend where you see it, at rest after tearing out the stump of the huge camphor tree immediately across the fence on my property line, which is just to the left of the shovel. While I was deciding where I had to be on the ledge to get the best composition possible, the woman next door stepped into her front garden. She didn't notice me, but watching her pick up leaves and such, I couldn't resist framing her in arch of the cherry picker as she stooped over in the opposite direction. My neighbor was not emulating the cherry picker. Rather the cherry picker was designed with what she was doing in mind. She scanned the ground and determined what she wanted to pick up. Her eyes sensed where the object was in relation to her hands. Her brain processed this information and manipulated her limbs and fingers to move in order to pick up the object and move it to another determined location. The machine merely extends the reach and strength of the human operator who becomes its "brain", thus enabling it emulate what he would do if he were bigger and stronger. The word "cybernetics" practically defined me in the late 1950s and early 1960s when I fancied myself becoming an electrical engineer -- or rather an electronics engineer. "Electrical" sounded like house wiring. "Electronics" involved vacuum tubes and other components of circuits in radios, televisions, and stereo amplifiers -- and, of course, oscilloscopes, which every electronic hobbyist dreamed of having. Both I and John Phelan, one of my best friends and accomplices in youthful electronic adventures, built an oscilloscope -- he as part of an electronic's correspondence source, I in the form of a Heathkit. I traded the oscilloscope I built to Burton Miller (1941-2013), another high school and Sierra College classmate, for part of his HO train collection. I then built another Heathkit, though a different, more compact model, which in time I closeted along with the manual. Years later I brought both to Japan, and a few years ago I gave the scope to my son. He occasionally turns it on to impress his friends. It still displays a trace that responds to signals, such as an audio output -- on Tokyo's 100-volt, 50-cycle current, no less. It smells just like it did in the late 1950s and early 1960s -- that smell of soldered wire that I consider the electronic equivalent of being in a bakery. The manual remains in my files at my residence in Japan. What we called "servos" were motors used in various "control systems" -- such as those that keep an airplane or rocket on course. A simple analogy would be a thermostat, which maintains (stat) the temperature (thermo) of a room, for example, at a preset value. If the temperature becomes too high or too low, sensors that measure the difference between the actual and desired temperatures send a signal to the heater to turn it down or up as the case may be. This is precisely what happens in your brain and body you are doing anything that amounts to slaving your muscular movements to your senses. And it is precisely what happens in the brain and body of the operator of a cherry picker as he or she demolishes a home, tears up the foundation and plumbing, loads the debris in trucks -- and, with different fittings, including a shovel, does the other work required to prepare a lot for a new home. The lot next to my home was cleared of 1 older house and 3 camphors to permit the building of 3 houses. One of the camphors was immediately next to my property. See Growth for a photographs of the two rounds I had the fellers cut from its trunk just above the stump and set in my garden with the cherry picker. |

EvacuationHelicopter blades don't stop in mid air, like those in the photographs to the right, except on high-speed film shot at a fast shutter speed in strong available light. The light that day couldn't have been better. I was standing immediately to the east of one of the 4-story ward buildings of the 106th General Hospital, at Kishine Barracks in Yokoyama. The name of the base reflected the name of neighborhood in which it was located, and fact that it had built shortly after the Korean War, mainly as a rest and recreation (R&R) facility military personnel in Korea and elsewhere in the region. It was fully self-contained facility with a chapel, baseball field, and swimming pool in addition to a movie theatre, clubs for officers and enlisted men, the indespensible PX, and a medical clinic. I was a member of the original complement of hospital personnel that were flown to Tachikawa in the Tokyo area from Ft. Bliss in El Paso, Texas, where the unit built up strength for a couple of months before being ordered to Japan. The unit had been based at Ft. Bliss as a semi-mobile field hospital, with a skeleton complement of personnel, who worked at William Beaumont General Hospital at the Ft. Bliss. The 106th was thus the STRAC (Strategic Army Corps) component of WBGH, which was included in the unit's address. But the 106th's tents and equipment were warehoused in readiness for deployment wherever it might be needed in a crisis or war. All equipment except the tents and mess facilities was shipped ahead of us and waiting at Kishine Barracks when we arrived in later December 1965 to set up the hospital. Most services were operating within a few days, and by January we were beginning to feel at home. I was a medical laboratory specialist in the 106th's Pathology Service as noted under Crusades above. I cannot remember when the first helicopter arrived. The one shown in the picture does not have medical markings, which does not mean it couldn't have brought patients. If it did, then the medical staff required to assist in bringing the patients to a ward would have been standing beside me ready to step out and help unload the stretchers or assist ambulatory patients.But perhaps this one brought some VIPs or materials that could not be delayed by conventional transportation. Hearing it coming, I stepped outside of the lab, which was immediately beside the block of wards to the to the west of the area came to be used as a helicopter port. If, by change, The 3-story building to the left (south) of the top picture is the smaller of 2 batchelor officer's quarters (BOQ). As its sign states, the low building just beside it is the Golden Dragon Club. Above the roof of the club you can see the top of the arch over the entrance to the base (bottom picture, not mine), and the building in the background (to the east) is the movie theater. The helicopter is a Huey, the workhorse of the Army at the time. I cannot comment on on its features except to say that it is the shorter model. If configured for use as a medevac ambulance, it could carry up to 4 stretchers in addition to a medical corpsman or other attendant -- the typical load of the standard M-43 3/4 ton 4x4 Ambulance Truck that I been trained to drive and attend as a medical corpsman at Fort Ord before I became a lab tech. The 106th also had a couple of M-43 ambulances. The driver of the one you see in the picture to the right accidently (I presume) backed through a fence and fell to the asphalt below it. The officer looking down at it was Lt. James Terry, the microbiologist I worked with at the pathology laboratory. As the duty officer that day, he had to write up the mishap. I documented him doing his duty with one of my trustee Pentax Spotmatics. He lived in the officer's quarters and had a car. The number of patients that arrived at one time varied. Sometimes they came by the busloads in busses configured with racks for stretchers. Some patients were ambulatory and could walk to their ward. The small Hueys, which could bring 4 patients on stretchers and more if they were ambulatory, could bring only two badly burned patients, as more space was needed for IVs and other support equipment and essential medical personnel. We got mainly wounded who had been evacuated by a helicopter or a field ambulance to an evacuation hospital in Vietnam. Extremely light wounds were treated in Vietnam. More serious wounds were treated to the point that the soldier could be transported to a hosptial outside Vietnam for further treatment. We got two kinds of wounded -- those we could treat and rehabilitate, usually in a matter of weeks, after which they would be returned to duty in Vietnam -- and those who we treated and stabilize to the point that they could be transported back to the United States for further care and recovery, including long-term rehabilitation for those with injuries they would have to live with the rest of their lives. At first we were primarily an orthopedic surgery hospital, meaning that we had a high ratio of orthopedic surgeons to other specialists. Mostly we got patients whose shattered limbs and joints could be mended, some with more need than others for long-term rehabilitation. A few patients required some degree of amputation, though out of necessity most amputations were performed in Vietnam, from which an amputee was sent directly back to the United States for further treatment and rehabilitation. So mainly we got patients whose injuries, though severe, had good prospects of being repaired. We also had malaria wards, for soldiers who were sent to us for recovery from malaria, but also for those who came to us with wounds who also turned out to have malaria. All patients were screened for malaria, as well as for intestinal parasites. And all wounds were cultured for bacterial infections. All this, of course, was lab work. So the mere sound of a helicopter, or notice that a convoy of busses was on its way, spurred us into action. The paved area area could accommodate as many as four helicopters, one in each corner, but that was a tight fit. I witnessed mainly serial arrivals, offloading, and departures. Helicopters usually came during the day, but a few came at night -- which was hazardous to say the least. Busses could come any time of day. There were also at least one, and as I recall later two neurology wards, which accommodated mostly patients suffering from from what was then commonly called "combat fatigue" but which involved more than simply weariness from battle and facing death. While I was there a burn ward was set up, and shortly after I left the 106th General Hospital became a regional burn center. The burn patients I witnessed and worked with had up to 30 percent burns, which can be critical but usually not fatal. who we found, through universal screening, to have malariasoldiers who we foundmay or not have been wounded but had malari, and a neuropsychiatry ward, U.S. Army reports on medical support in Vietnam made the following observations about the role of the 106th General Hospital concerning "secondary care" for surgery patients, especially those that required orthopedic surgery, and "burns" [bracketed remarks mine]. Secondary careSecondary wound care, which included the management of wound closure, wound breakdown, wound infection, stabilization of long bone defects, and similar problems, was not ordinarily handled in Vietnam. Although reexploration for surgical complications indicated by fever, pain, excessive drainage, or vascular compromise was encouraged whenever and wherever they appeared, most secondary wound care took place after the patient was evacuated to the 106th General Hospital, in Yokohama, Japan; the U.S. Air Force Hospital at Clark AFB [Philippines]; Tripler Army Medical Center in Hawaii; or CONUS [continental United States]. Source Orthopedic Surgery in Vietnam, Medical Department, United States Army Surgery in Vietnam, Orthopedic Surgery, Editor for Orthopedic Surgery, Colonel William E. Burkhalter, MC USA (Ret.), Chapter 1: The Soldier and His Wound in Vietnam, Colonel John A. Feagin, Jr., MC, USA (Ret.), The Milieu, Care of the Soldier's Wound, page 9. BurnsThe most unfortunate aspect of the burn injuries incurred in Vietnam was that more than half were accidental and therefore preventable. Burns associated with enemy fire, while fewer in number, accounted for almost 70 percent of the fatalities because of their severity and associated wounds. A factor in the high mortality was that most combat burns occurred in an enclosed space, such as an armored personnel carrier or a bunker, and were, therefore, complicated by inhalation injuries. Burn cases were stabilized in-country and then evacuated to the 106th General Hospital in Japan, where a special burn unit had been established. Of the burns treated by the 106th, 27 percent returned to duty, 66 percent were evacuated to the burn unit at Brooke Army Medical Center, Fort Sam Houston, Tex., and 7 percent died. Source VIETNAM STUDIES, MEDICAL SUPPORT OF THE U.S. ARMY IN VIETNAM 1965-1970, by Major General Spurgeon Neel, DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY, WASHINGTON, D.C., 1991, CHAPTER III: Care of the Wounded, Nature of Wounds, Burns, page 56. |

FishingForthcoming |

Mt. FujiMt. Fuji -- Fuji-san (most commonly) or Fuji-yama (occassionally) -- is probably the globally best-known symbol of Japan. Despite what Japan's 1947 Constitution says about the Emperor being the symbol of the country, people in Japan and elsewhere, who have no idea what the emperor looks like, or even that there is an emperor, are likely to recognize Mt. Fuji. Mt. Fuji, like many mountains, has been considered sacred and forbidding. Few people dared to climb it until the late 19th century. Fuji consists of several volcanic cones, the result of older and more recent eruptions, which have figured in the geological history of the region. One of Fuji's volcanoes was last active in the early 1700s. Everytime a more active volcano spews fumes or lava, or an earthquake strikes the area, some Fuji observers warn that it due to blow. Like the "big one" that experts say is someday bound to jolt the entire country off its geta, the prospects of Fuji popping and leaving but a scar on the face of the earth keeps some people awake at night. Mt. Fuji's dominant crater is visible from many locations within a range of about 300 kilometers. It is easy to see from many places in the Kantō plain, where "Fuji-mi" (富士見) or "Fuji-view" place names are common -- including Fujimi-shi, a city in Saitama prefecture. Among the rewards for working at the 106th General Hospital at Kishine Barracks in Yokohama for 9 months during the Vietnam War were the views of Mt. Fuji on the horizon above the Tanzawa range on clear sunrises, noons, and sunsets.

TriangulationI took the photograph of Mt. Fuji and Skytree only 200 steps from my home in Abiko. If I were to cut across my neighbor's garden on a straight line, it would take only 100 steps. On the right is Mt. Fuji, 146 kilometers away from my neighborhood vantage point in Abiko, on a line bearing 237 degrees. On the left is Skytree, 25 kilometers away and bearing 226 degrees. Mt. Fuji is 119 kilometers from Skytree on a line that bears 240 degrees. Mt. Fuji, Skytree, and my vantage point define the vertices of a triangle. Can you compute the angles of the triangle? Hints Compass bearings are measured clockwise from the North. There are 360 degrees in the full sweep of the compass -- from North (0°), then East (90°), South (180°), West (270°), and back to North (360°). The sum of differences between the bearings of all lines that define the circumference of any enclosure of any shape, from a triangle to a circle, is 360 degrees. However, the sum of the internal angles of a polygon varies from 180 degrees for a triangle, to 360 degrees for a quadrangle, 540 degrees for a pentagon, and so on, according to the formula (n-2)*180° where "n" is the number of sides. As the number of sides approaches infinity -- as it would in the case of a circle -- the sum of the internal angles also approaches infinity. On a map of Japan, I could draw bearing lines from Mt. Fuji and Skytree, observed from my Abiko vantage point, and in theory they would intersect where I stood. This is the principle of triangulation -- one of most common pre-GPS-era methods of confirming one's position on the ground -- i.e, by measuring the bearings to two known visible landmarks relative to one's own position. At night before the GPS age, navigators, explorers, and surveyors shot the stars. |

|||||||||

Growth (Hakusan, Abiko, 2014)You are looking at the top of the 2nd and smaller of 2 rounds cut from the trunk of a neighbor's camphor tree just above the stump. The tree was just on the other side of our common property line. I have not yet attempted an accurate count, but my guesstimate is that the tree had been there for about 70 years. A demolition crew cut it and 2 other camphors of similar size on the other other side of the lot near the main gate of the neighbor's house, to make room for 3 new houses. The neighbor's house had been about 50 years old. The woman, who survived her husband, taught tea ceremony until she could no longer walk well enough to shop and care for the house, which was one of the oldest and largest in the neighborhood. It a huge front garden by Japanese standards with large boulders and a number of small trees and bushes in addition to the camphors. There were about 2 meters of space on its east and west sides, and roughly 3 meters between the northern back side which faced faced the south side of my lot. The camphor nearest me filled the western window off my 2nd-story study, bedroom, and veranda. It sheltered a number of nests, most musically those of bush warblers that serenaded the neighborhood on summer mornings. The south side of front garden is now overshadowed by the walls of two homes that I can practically touch, the setbacks are so small. In summer I get enough sunlight for a small vegetable patch. From late fall to early spring, most parts of the garden don't see the sun. Snow, though rarely very heavy, is slow to melt, and at the height of winter, one night's hoarfrost will form before the previous night's hoarfrost has thawed. The long approach to my home, along the south side of my lot, is an ice corridor. The in the photograph is about 80 centimeters across. The stump was over a meter. The scar represents what I surmise was a lightning strike about 20 years into the life of the tree, which survived another 50 years. If it hadn't been cut, it might have gone on for a few hundred years. There is no accounting for the loss of old trees in the neighborhood, which used to be dotted with camphors. The first wave of subdividing the larger farms and estates in the area took place about 50 years ago. The lots then ran about 100 to 150 tsubo -- 8-12 percent of an acre figuring 1,224 tsubo/acre. At land princes today, few middle-class people can afford more than 35 to 50 tsubo, or 3-4 percent of an acre. But this is enough for the footprint of a 3-4 bedroom home with small setbacks and short eaves. Many people today actually prefer the smaller, more crowded lots in order to avoid the upkeep required for lots with more space around the homes. The newer style homes prefer a slab of concrete to park a car or two immediately in front of the house, in lieu of a wall, gate, and small front garden, and a parking slot along the side of the house. The fire hazards created by older wooden homes when too closely spaced are no longer a problem, as newer homes, though most are still framed with wood, are generally closed with inflammable materials. Fewer windows and no back doors, and stronger window gratings and other security measures, mean less risk of a break-in. My own home is an anomaly, built on a long narrow 60-tsubo. The footprint has a setback of about a meter on the sides and half again as much in the back, which leaves a postage-stamp garden in front. This lot is set back by a 24-meter long, 2.7 meter wide approach which comes to about 20 tsubo. It's all very tiny by suburban and even urban American standards, but rather comfortable by Japanese standards. I am blessed by the fact that my northern neighbor's house is a rare 1-story model and is surrounded by a very large, park-like garden, which produces all manner of vegetables and fruits, and is home to a number of toads and rain frogs. The trees attract birds, the blossoms bees, and the soil moles, which have a free run of my property too. See Snow for a wintry view of this home. |

HiganbanaForthcoming |

HomeForthcoming |

||||

IsezakichoForthcoming |

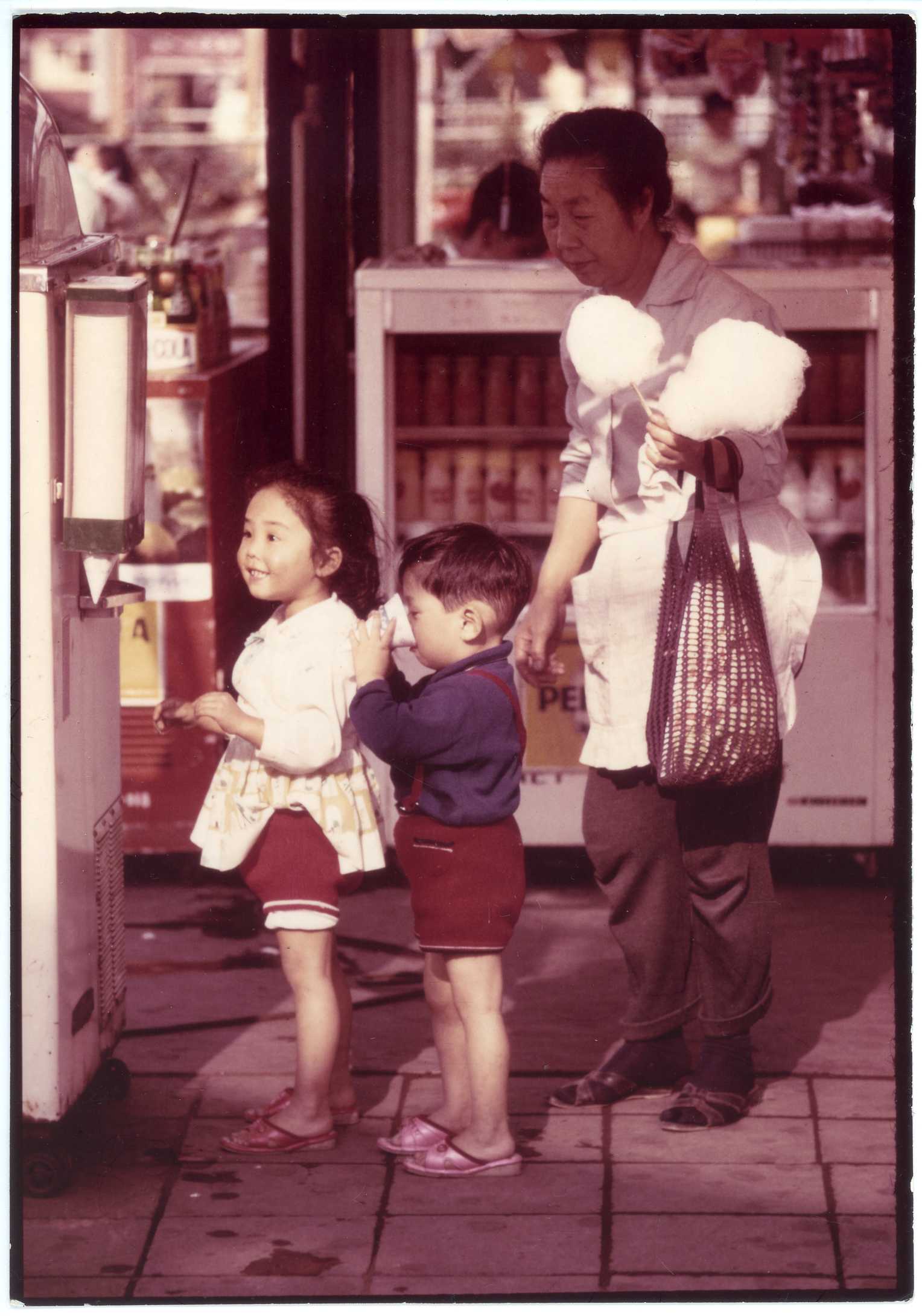

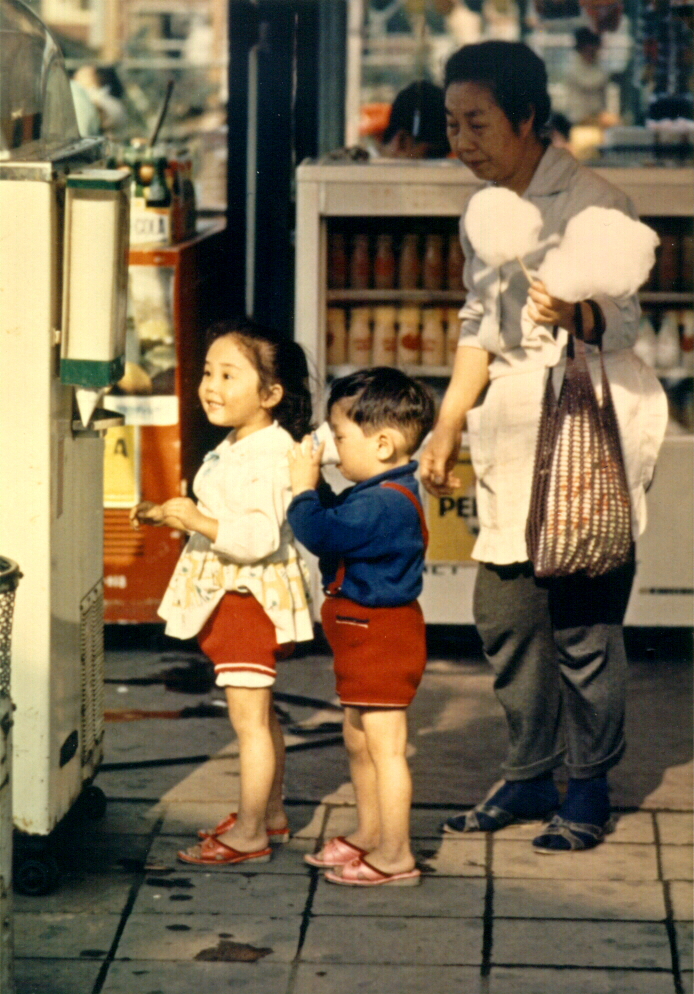

JoyThe image to the right is 300dpi scan of a duplicate of the print I sent to Asahi kamera (アサヒカメラ) in 1967. The print measures roughly 12.5x18 centimeters or 5x7 inches. The print is an enlargement of a color positive. The information I was required to supply with the submission is recorded on the back of the duplicate copy as follows.

The submitted print is only slighly cropped from the original 35mm composition. The crop is based on my instsructions to the printer, which I marked on an enlargement of a full uncropped contacty print of the slide. The print was made on a smooth surface semi-glossy paper. I don't remember its specs, but the resolution is extremely high. The image to the right was scanned at 300dpi, but the definition holds up even at 1200dpi. By comparison, a print I later had made on matte paper, directly from the transparency, while truer in color, is even to the naked eye of lower resolution (the leftmost of the paired images to the right). I did not request hand processing, and I suspect the printer let his printing machine decide the image area, which inevitably slips a bit around the original picture (a common problem when scanning film). The resulting composition is inferior. Again by comparison, the 3200dpi scan I made of the original transparency, entrusting the image area to the scanner, resulted in practically the same inferior composition, and a somewhat darker image, though again seeminly truer to color (the rightmost of paired images). I cannot at this date, nearly half a century after taking the picture, and practically that long since the semi-gloss and matte prints were made, say to what extent they have suffered changes in color over time -- except to say that, never mind how carefully I have stored them, changes are inevitable. What hasn't changed -- is the story told by the expressions on the faces of the girl, her brother, and their grandmother. I am, of course, just guessing their relationship. But what else could they be to each other? The children resemble each other, and you could imagine that the girl will look like the women when she's her age. The woman could be a maid, but the demographic odds are against it. The boy is too engrossed in his soft drink for anything else to matter. The girl has dropped the 10-yen coin her grandmother has given her into the slot and is watching the conical paper cup fill, anticipating the flavor of the softdrink -- possibly for the first time. Judging from the different sizes of the cotten candy that remains on the sticks, the children have already had some of it. The woman probably bought nothing for herself but just took quiet delight in watching her grandchildren have fun. |

|||||

KinshipForthcoming |

LotusForthcoming |

MobForthcoming |

ParfaitForthcoming |

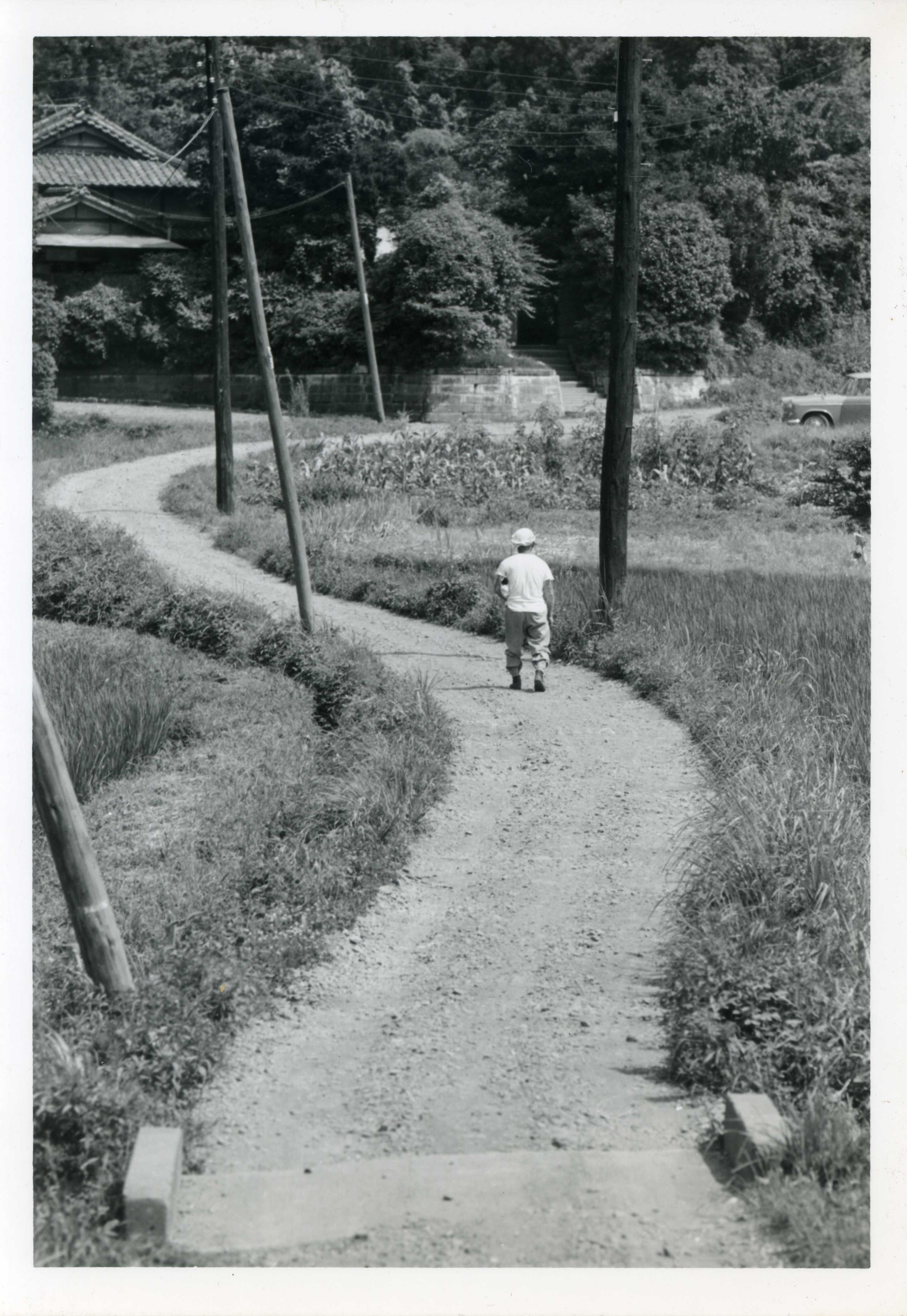

RoadI took this shot while walking around the Shinohara area between Kishine Barracks and Shin-Yokohama station in Yokohama in 1966. The military base is now a park. I have not been able to pinpoint the location of the road winding through the fields and its intersection with road running along the fields and the foot of the forested hills in the background. Practically all the fields in the larger area are gone, and the suburban sprawl has all but destroyed the older geographical features. VerticalsWhen framing a picture, I look for a vertical reference. The edge of a wall, door, or bookcase when indoors, or when outdoors the edge of a building or telephone pole. The reference may be in the foreground or background, but wherever it is, all other verticals in the picture are considered in relationship to it. If imperative that dominant verticals appear to be parallel, then I position the camera in order to align them. If, say, taking a photo of hallway, which has pillars and doors or other verticals, I might take a pillar to the left of the picture as the vertical reference, and angle the camera so that a door frame on the right is parallel to the piller. The problem I faced when shooting the picture of the winding road is that the most dominant verticals are not parallel, All of the poles were leaning in different directions. The only candidates for alignment were the house in the background and the man. The eaves of the house on the left and the car on the right served as horizontal references. In the end, I opted to make the man in the center the primary vertical reference. I had been walking a short distance behind the man, and I didn't take an interest in the road across the field it until suddenly he turned right. When I reached the road, he was about halfway between the main road and where I caught him in the picture. I immediately began framing -- making composition and orientation decisions -- and looked for a moment to shoot. And I shot just this one shot, with a 150mm lens on a Pentax Spotmatic, and continued walking. The image shown here is my scan of an enlargment made by Bill Harvey in the X-Ray department at the 106th General Hospital at Kishine Barracks in 1966. |

SnowForthcoming |

TanzawaForthcoming |

ThatchingForthcoming |