Tokyo's 1872 Ishiki kaii jōrei

Policing public order, safety, hygiene, and morality

By William Wetherall

First drafted 18 November 2007

Last updated 9 June 2021

Social order

Police powers

•

Punishments

•

Ishiki offenses (infractions)

•

Kaii offenses (mishaps)

Sources

Yubin hochi shinbun (No. 27)

•

MOJ version (1872)

•

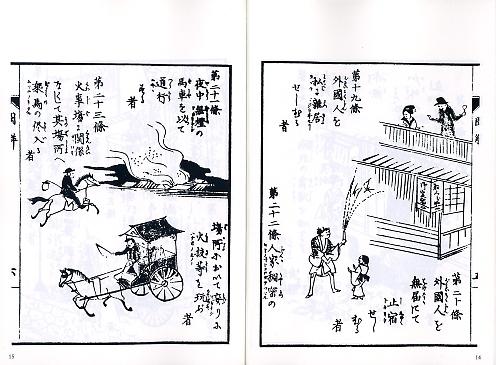

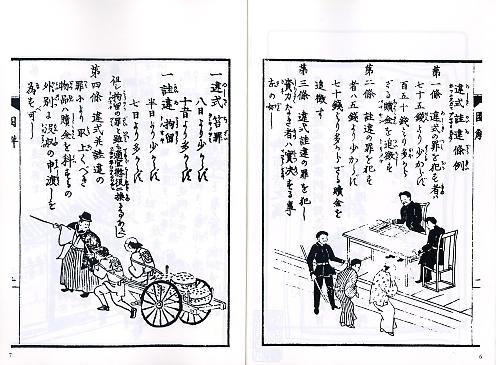

Ishiki kaii zukai (Nagoya 1878)

•

Recent commentary

Social order

On Meiji 5-11-8 (8 December 1872), barely three weeks before Japan would begin to officially use the Gregorian calendar, the governor of Tokyo (Tokei) prefecture (東京府) promulgated an ordinance called Ishiki kaii jōrei (違式詿違條例). This, literally, was a body of articles concerning (1) "ishiki" (違式) or "violated conventions" and (2) "kaii" (詿違) or "implicit violations".

Very roughly speaking, "ishiki" -- the more serious offenses -- were violations of a stipulated standard -- contraventions of regulations or laws, transgressions, infractions. Whereas "kaii" -- the less serious offenses -- were acts of negligence, mishaps, or accidents that disturbed the public, damaged property, or injured others. Like most such labels, whether in Japanese or English, such terms do not define themselves, and are best understood through examples (see below).

The 1872 Tokyo ordinance, consisting of 53 articles, was an attempt to discourage a number of behaviors -- which in some quarters might be considered customary or at least not objectionable -- that the government regarded as contrary to public hygiene, safety, order, and decency in the new country's capital province. Many amounted to what today are part of traffic safety, public health, and consumer protection laws.

New legal order

During 1868, the Tokugawa government, under the Tokugawa clan, was replaced by an imperial government organized under the nominal authority of the emperor.

Until this change, the Tokugawa clan had been delegated by the imperial court to oversee all of Japan's affairs, within the provinces and with other countries. The clan did so with the help of its closest allies, and in accordance with mostly century-old standards.

The leaders of the new imperial government had overthrown the Tokugawa shogunate with the intention of introducing an entirely new political and social order in the country. They sought, in short, to nationalize the provinces into a state that in not too many years would be able to stand shoulder to shoulder with the Euroamerican countries with which Japan had signed unequal treaties in the 1850s and 1860s.

The treaties, with the United States, Great Britain, and other non-Asian countries with interests in East Asia, established open ports with foreign settlements in which these states would exercise their own laws. Extraterritoriality was an acknowlegement that Japan was not yet legally competent in the eyes of the other states, and in signing the treaties Japan accepted the challege to reform its legal system to the point that they would recognize Japan as a peer among the world's powers.

New social order

Even before the new leaders took the reigns of government, however, some local Japanese societies had begun to move in the directions the leaders proceeded to lead the entire country. Under the final years of the Tokugawa government, life around the ports that had been opened to foreign commerce, and of course in Edo, had visibly changed, as is clear from many nishikie and some photographs from the period.

Once Edo was renamed Tokyo or Tokei, which designated its new status as the capital of a state and not just the locality of a castle, change accelerated. Practically everything began to rapidly change -- from social classes to modes of travel, communication, housing, dress, coiffure, cuisine, entertainment, publishing, writing, speech, even thought, and use of foreign languages -- and of course law and its enforcement concerning all imaginable matters, including public behavior.

Some quarters of society drifted to the brink, one could argue, of chaos or anomie, as happens when a society's compass becomes eratic and people lose their bearings. New ways of life, including new freedoms, burst the seams of older standards. The new authorities were challenged not only by new excesses, but also by familiar behaviors that had generally been tolerated but now became problems.

Not just outside pressure

A lot of ink has been spilled in English and Japanese to the effect that the Ishiki kaii jorei of 1872 was mainly an instrument of "westernizing" Japanese morality. But this was not the case.

Only a few of the articles in the ordinance concerned behaviors that might be construed as particularly offensive to some "Westerners" or "Christians" or "Victorians" or others in a position to witness the behaviors and express their feelings about them to authorities. The bulk of the articles addressed matters that would require some degree of regulation in any society -- regardless of pros and cons within the society or forms of "outside" pressure.

It is true that "nudity" was likely to embarrass or invite the glare of some of the aliens, men and women, who had begun to frequent the streets of Tokyo, among other towns near open ports, in greater numbers. But it does not follow from this that the proscription of nudity in public -- the most commonly cited example of "Westernization" in the 1872 ordinance -- did not also reflect the sensitivities of Japanese who thought bodily exposure in public to be vulgar.

Ishiki offenses (infractions)

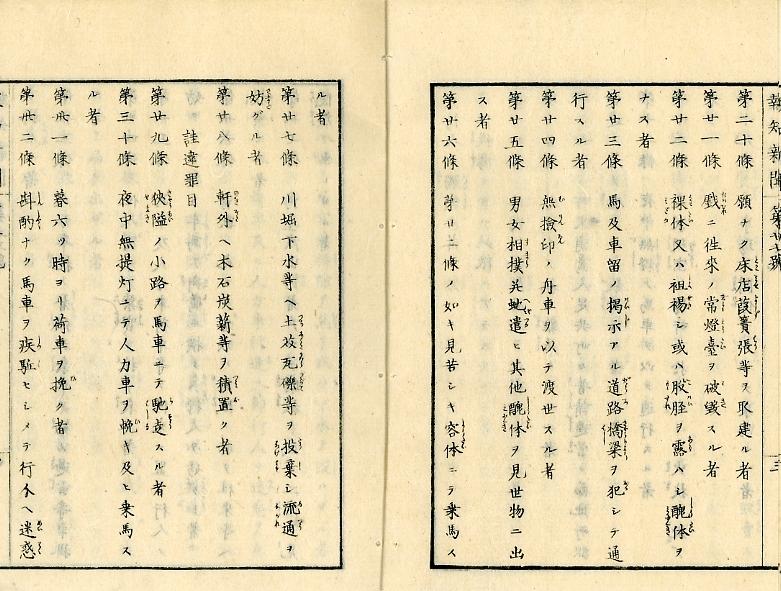

A number of the offenses, though, had to do with decency and morality -- such as selling spring (erotic) pictures (Article 9), needlework on the body (tattooing) (Article 11), mixed bathing (Article 12), being naked, or exposed from shoulders to waist, or baring one's loins, or otherwise forming an unsightly body in public (Article 22), sumo between a man and woman, snake handling, or otherwise displaying an unsightly body as a spectacle (Article 25).

It was also an offense to give lodging to an outlander without permission (Article 14), or personally "mix residence" (雑居 zakkyo) or "cohabit" (promiscuously live) with an outlander (Article 15).

Kaii offenses (mishaps)

A woman was not without reason to cut her hair (Article 39), or urinate or deficate in front of stores or along thoroughfares (Article 49).

Sources

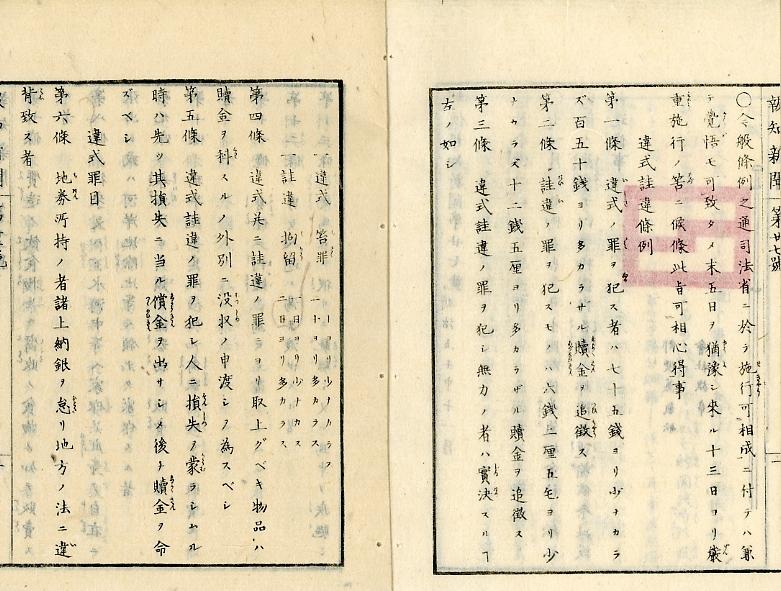

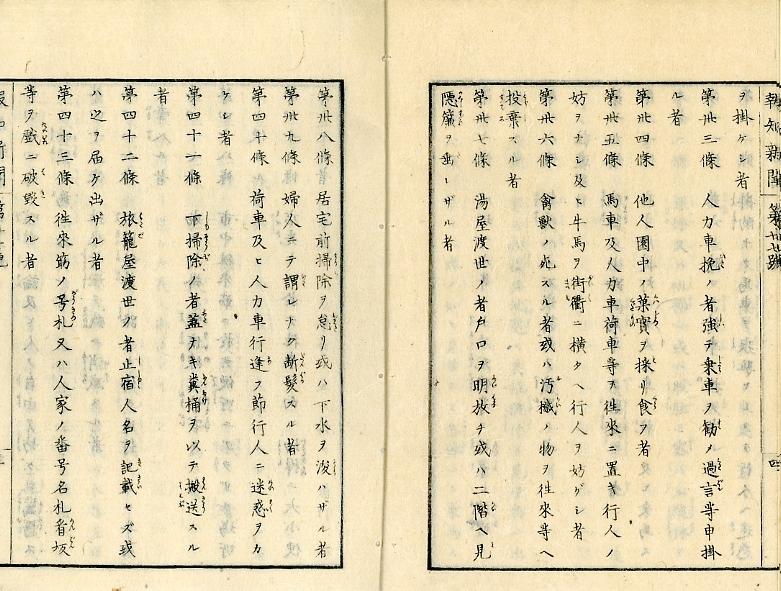

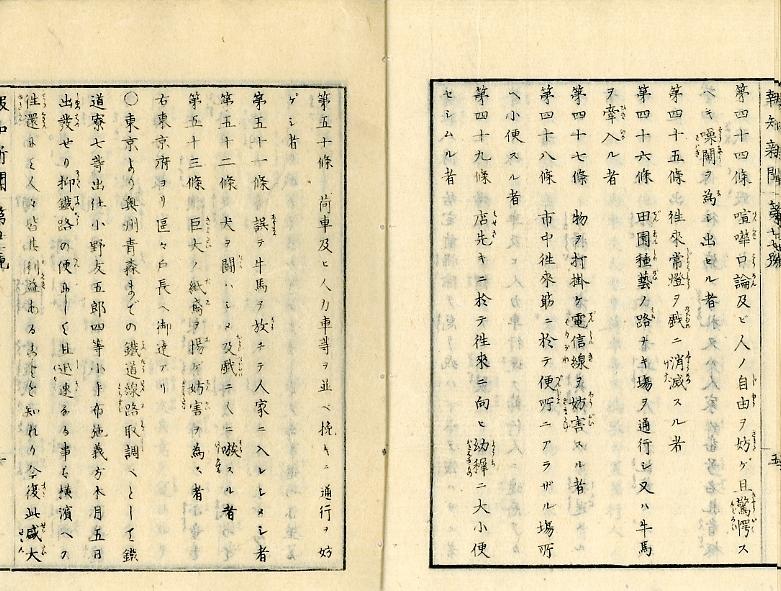

The version of Tokyo's Ishiki kaii jōrei described here is the 53-article original as printed in Yūbin hōchi shinbun immediately after its promulgation by Tokyo prefecture. The version adopted by the Ministry of Justice is one article longer (see below).

Comments on the 54-article MOJ version are based on a printed version in a collection of late-19th-century Japanese laws readable online through the National Diet Library (see next). Comments on revisions and the eventual lapse of the Tokyo ordinance are also based on this collection and on other sources are as noted.

National Diet Library Meiji era database

Early Meiji ordinances can be found through the National Diet Library Dajokan database, which links to scans of texts in NDL's Recent era digital library, officially dubbed "Digital Library from the Meiji Era". See Meiji volumes of Horei zensho in the "Legal terminology" section of the "Glossaries" feature of this website for more information about HRZS and the NDL databases.

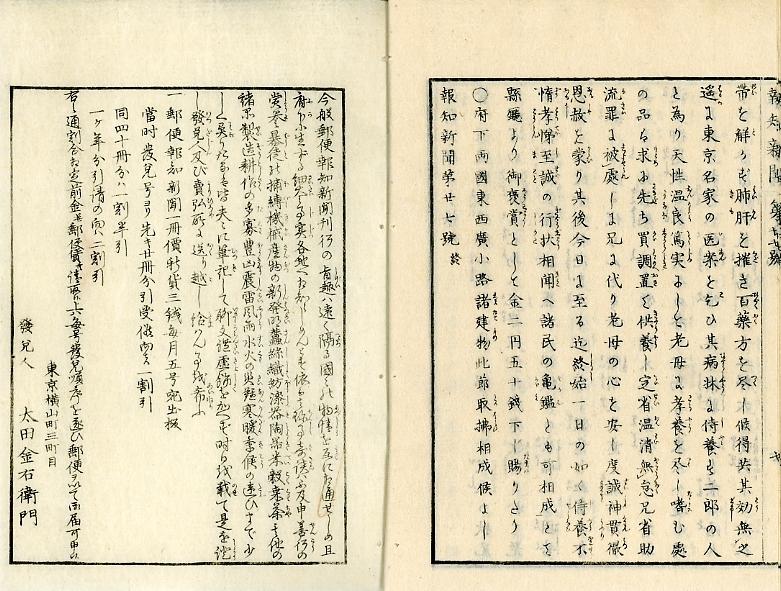

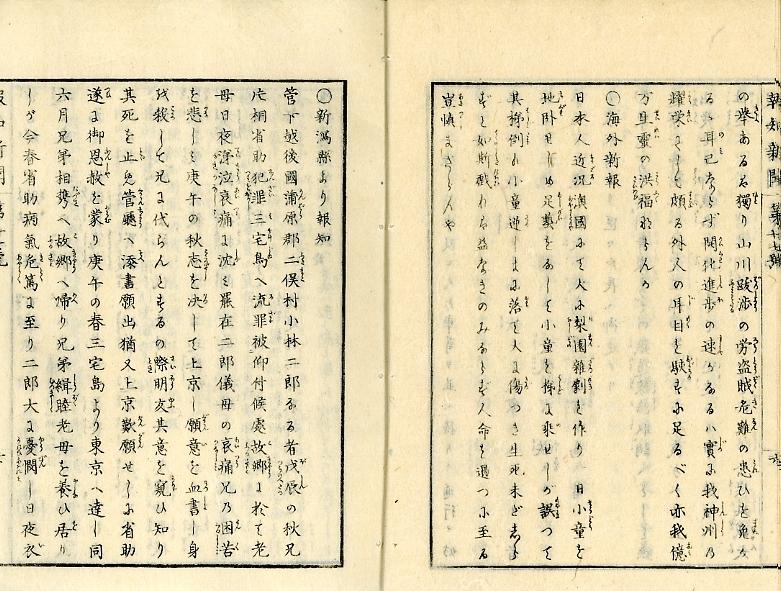

Yubin hochi shinbun (Number 27)

All citations of Ishiki kaii jōrei in this article are from the copy of the ordinance as published in the 27th issue of Yūbun hōchi shinbun at the end of 1872. The cover date of this issue is "Meiji Jinshin-nen 11-gatsu", a sexegenary cycle version of Meiji 5-11, a lunar date roughly corresponding to December 1872, which was on the eve of Japan's official adoption of the solar calendar.

Official use of the lunar calendar ended on Meiji 5-12-2 (31 December 1872). The following day became Meiji 6-1-1 (1 January 1872).

The cover date was shared by four or five other issues published that month. For more about the founding and development of Yūbin hōchi shinbun, and details about its early issues, including Number 27, see Hochi early issues: News dispatches by postal conveyance at the News Nishikie site.

Practically the entire issue of Number 27 was given to the 53 articles of the Tokyo prefecture ordinance. The ordinance filled nearly ten pages (1b-6a) of what was then a 7-folio, 14-page news pamphlet published about five times a month.

Ministry of Justice ordinance (1872)

Immediately after Tokyo issued the Ishiki kai jōrei, the Ministry of Justice (司法省 Shihōshō) issued an essentially identical ordinance. The MOJ version, which had an addition article, was enforced from Meiji 5-11-13 (13 December 1872), just 5 days after the Tokyo ordinance.

The MOJ version had 54 articles -- one more than the Tokyo ordinance -- as a result of adding an additional article, as Article 46, following Article 45. Articles 46-53 of the Tokyo ordinance thus correspond to Articles 47-54 of the MOJ version.

Over the next few years, new articles were added, and older articles were revised while some were deleted or merged, practically monthly. At times the ordinance had over seventy articles.

The expanded and revised MOJ ordinance lapsed with the enforcement from 1 January 1882 of the first "Penal code" so-called (刑法 Keihō) promulgated by Great Council of State Proclamation No. 36 of 17 July 1880.

A copy of the MOJ version can be found in "Complete book of laws and ordinances" (法令全書 Hōrei zensho, HRZS), Volume 7, Meiji 5, pages 1349-1355).

Early Meiji ordinances can be found through the National Diet Library Dajokan database, which links to scans of texts in NDL's Recent era digital library, officially dubbed "Digital Library from the Meiji Era". See Meiji volumes of Horei zensho in the "Legal terminology" section of the "Glossaries" feature of the Yosha Bunko website for more information about HRZS and the NDL databases.

Ishiki kaii zukai (1878)

The Ministry of Justice, in adopting Tokyo's ordinance, signaled that its articles were to be regarded as a standard for other prefectures. signaled to and imm's adoption and of Tokyo's ordinance with an addition article -- one articlepromted many prefectures as a to promulgate their own versions. The , which typically had more articles.

Recent commentary

Among several Japanese studies on various local adaptations of the Tokyo ordinance, the following article is one of the more interesting with respect to the manner in which Haruta categorizes the various offenses. A PDF file of the article is available from 別府大学機関リポジトリ or "Beppu University Information Library for Documentation" (BUILD).

春田国男

違式詿違条例の研究

(文明開化と庶民生活の相克)

Ishiki kaii jōrei no kenkyū

(Bunmei kaika to shomen seikatsu no sōkatsu)

[ A study of Ishiki kaihi ordinances

(The conflict of civilization-and-enlightenment and the lives of the common people) ]

別府大学短期大学部紀要

第13号 (1994), ページ 33-48

Kunio HARUTA

A research of Ishiki Kaii ordinance

(The conflict of Westernization and the common people's life in Japan)

Bulletin of Beppu University Junior College

Number 13, 1994, pages 33-48

Do not be misled by the odd "Westernization" of Haruta's English title and abstract. His report actually shows that most of the "ishiki" and "kaii" were about maximizing the qualify of life in an urban society in ways unrelated to "westernization".

To be sure, some of changes rushing upon Tokyo prefecture were inspired by novelities inspired by the increasing presence of Euroamericans in the country. But society in the new prefecture, shaken from the foundations that had disciplined life in Edo even as the Tokugawa government was losing its grip elsewhere in the country, was long overdue for corrections and clarifications in the rules of conduct essential to organized life.

The following English sources include somewhat different but useful overviews of the ordinance in relation to other contemporary laws and their enforcement.

William Röhl

Administrative Law (Part 2.2) of Public Law (Chapter 2)

In William Röhl (editor)

History of Law in Japan Since 1868

Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers, 2005

(Handbook of Oriental Studies Section Five, Japan)

Civilization and Enlightenment (Chapter 7)

In David L. Howell (author)

Geographies of Identity in Nineteenth-Century Japan

Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005