The empire of passports and IDs

Documents essential for travel and work

By William Wetherall

First posted 1 December 2009

Last updated 15 December 2009

Last edited 6 August 2017

Identification

Passports and other certifications of affiliation, status, and authorization

Imperial Japanese passports

1866 Servant

•

1878 Heimin

•

1922 Interior Shizoku

•

1924 Interior family

•

1937 Chosen family

Imperial Korean passports

1905 Korean gentleman

Imperial Manchou national handbooks

1945 Mongol cultivator (29 pages)

•

1945 Han farmer (8 pages)

US immigration documents

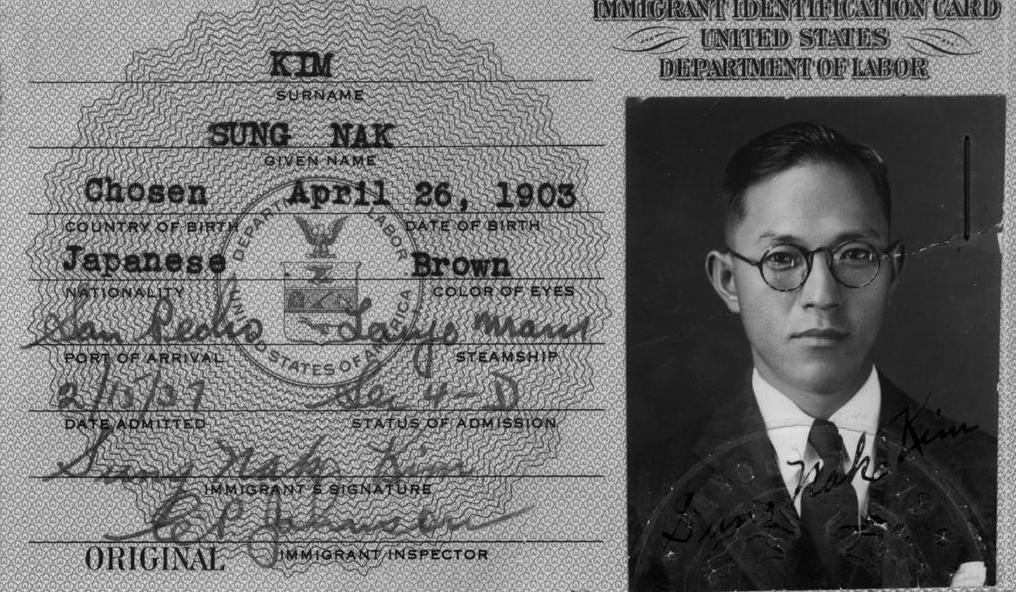

1937 Immigrant ID Card for Chosen Japanese

Personal identification

How do you prove who you are? In interpersonal encounters, you depend on your ability to recognize someone you already know, and expect people who already know you to recognize you. If you are famous or infamous enough to appear on the evening news, night after night, total strangers will recognize you -- or mistake you for the person if there is some resemblance.

Similar (or different) gross physical features suggest similarities (or differences) in gender, race, social class, cultural patronage, country of origin, among many other aspects of apparent identity -- and you could easily be wrong in your estimates of who another person really is -- as others could be of you.

Fingerprints, DNA, and numerous less obvious visible and invisible physical traits, some requiring elaborate technology to reveal or confirm, can be used to differentiate individuals for many purposes, from authentication of identity at a port of entry, to correlation of crime scene evidence with a suspect.

Passports

A "passport" is literally a document that one needs to "pass" through a "port" of any kind across any sort of border. The "border" can be within the same country.

States issue a variety of passports, some for general use, others for official or diplomatic use. Some states issue different kinds of general-use passports for different statuses of nationals. Some semi-autonomous jurisdictions within states issue their own versions of the state's passport (Hong Kong).

In international travel, passports are used to differentiate between nationals and non-nationals, and even between various classifications of nationals and non-nationals, for purposes of vetting people's identities and determing who may cross a check point. Nationals and non-nationals alike may be prevented from passing, or conditions may be attached to crossing.

In most circumstances, nationals and non-nationals with valid documents, following established procedures, are allowed to cross borders -- into and out of ports including airports, or across borders in the case of land travel. Validity of documents and properness of procedure are essential.

A Japanese man who was widely reported to have set off to cross the Pacific in a balloon had failed to clear his departure from Japan with exit-enter-country [immigration] control authorities. Authorities planned to detain the man and investigate his actions when, whether by baloon or other means, he returned. Unfortunately, he disappeared without trace.

Passport particulars

The data page of a passport identifies the bearer by name, gender, date of birth, and nationality, and and also contains information about the passport, including the issuing authority, a serial number, and dates of issuance and expiration.

The message page is a boiler plate statement, usually from the issuing state, addressed to other states, to the effect that the issuing state requests other states to treat the bearer well and render protection and assistance if needed.

Both the data and message pages, and other printed content of the passport, are typically in at least two languages. English and French are probably the most likely second languages to be used on passports of countries that do not officially use either of these languages.

The French EU passport shows the message in all EU languages.

Machine-readable passports

Convenient, quick, and secure border crossing has become essential in this age of mass global air travel. The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), a UN Specialized Agency, sets and recommends passport standards, which most states immplement in their passport designs and recognize in their mechanical passport readers.

ICAO's strategic objectives as of 2005 were as follows (ICAO website).

- Safety - Enhance global civil aviation safety

- Security - Enhance global civil aviation security

- Environmental Protection - Minimize the adverse effect of global civil aviation on the environment

- Efficiency - Enhance the efficiency of aviation operations

- Continuity - Maintain the continuity of aviation operations

- Rule of Law - Strengthen law governing international civil aviation

ICAO requires that all contracting states issue machine readable passports (MRP) compliant with its standards from 1 April 2010 and that all non-MRPs should expire by 1 April 2015. The legal and technical issues are extremely complex. The argument for global-standard MRPs is as follows (from paper on "Reinforcement of Compliance in the Production of Machine Readable Passports (MRPs)", presented by the New Technologies Working Group (NTWG) at 19th meeting of the Technical Advisory Group on Machine Readable Travel Documents (TAG-MRTD), Montreal, 7 to 9 December 2009 (pdf file retrieved 2 December 2009).

The value of a MRP is significant; it provides a globally interoperable travel document; it is more secure than a handwritten travel document and it is formatted in a way that is recognisable to border authorities, visa officers, airlines etc.; it provides a more effective method of checking watch lists. The project proposal stated 'The overall aim will be to reduce the number of countries that appear on the list of non-MRP issuers'.

MRPs are of a uniform physical format and incorporate uniform security features that permit personal identification for all the above purposes.

The data page is printed with optical readable characters. Some of the essential information is coded by numbers. The information may also be contained on an embedded electromagnetic storage device of the kind used on smart cards.

Some states issue biometric passports which use the technology of smart cards. An embedded storage device has encrypted information about the issuing authority and the bearer, including a digital photograph of the bearer.

Some states also issue ePassports, which are smart cards. The cards contain the usual encrypted information and require recognition by a public key.

Nationality

States, in their domestic laws, have used various terms to identify their national affiliates -- subjects, nationals, non-national subjects, citizens, non-citizen nationals, et cetera. A state's laws, taking such variation in domestic usage into account, may refer to affiliates of other states as "subject or national" or "citizen or national" and the like.

Today, "nationality" is the internationally recognized term for affiliation with a state. A person who lacks a nationality is "stateless". Some people have more than one nationality, but are generally permitted to declare only one nationality at a time in situations that require classification of a person's legal status -- such as when entering or leaving a country, or in legal actions that require determination of applicable laws.

Visas and other permits

While a country's nationals generally have a right to be the country -- though not necessarily the right to be unconditionally free to leave or enter the country, or to live freely in the country -- aliens generally require specific permission to transit, travel, sojourn, or reside in a country. The most common kind of permit is called a "visa".

A visa determines the parameters of an alien's activities in a country. Most visas are for limited activities and limited terms. Some countries use the term "visa" only in reference to a "limited activity" status, while unrestricted long-term or permanent statuses of residence are not classified as visas (Japan, for example).

Immigrant

The term "immigrant" generally means a person who is permitted to enter a country and remain permanently. Some countries do not have "immigrant" visas since aliens must be residing in the country to apply for permanent residence (Japan, for example).

The United States has both quota and non-quota immigrant statuses. Quota immigrants are treated according to conditions that limit the number of immigrants permitted to take up permanent residence in the United States from a particular region of the world in a given year. Non-quota immigrant statuses are those that are granted on the basis of personal circumstances regardless of quota conditions.

Imperial Japanese passports

I have seen a number of older printed Japanese passports, with issue dates ranging from 1878 to 1937. I possess three passports of similar design, one issued in 1911, the other two in 1924.

All these passports use the term 旅券 (ryoken) or "travel certificate" -- the standard term for "passport" in Japanese by 1878. Before then, a variety of other terms had also been used.

Broadly speaking, there were two stages in the history of printed passports up to 1945. First stage (1878-1926) passports, consisting of single folded sheets, were called 海外旅券 (kaigai ryoken) or "outside [beyond] seas [overseas] travel certificate [passport]". Second stage (from 1926) passports, of booklet form, were called 国外旅券 (kokugai ryoken) or "outside [beyond] country travel certificate [passport]".

In this section, I will show and tell examples of 1878 and 1937 passports found on other sites, as well as the 1911 and 1924 passports in my own possession. First, though, I will summarize the three-part overview of the history of passports in Japan as presented in virtual exhibits on a National Archives of Japan website.

National Archives passport exhibits

The National Archives of Japan (国立公文書館) has a three-part passport history exhibit on its ぶん蔵 (Bunzō) website.

Late Tokugawa and early Meiji passports

The first part begins with a bright-eyed girl Clara (くらら) telling Dr. Bunzō (ぶん蔵博士), a friendly-looking professor with rimless glasses, wavy longish hair, and a moustache, that she will be going to Paris over the coming vacation. She proudly shows him her passport and they begin to discuss the history of passports.

Dr. Bunzō explains that the first passport-like documents in Japan were issued in Keiō 2, or 1866, some 13 years after the appearance of Commodore Perry off Japan's shores. The earliest passports were limited to travel for study and commerce in countries with which Japan had signed treaties, he says. However, the content of the 1866 passport shown in the exhibit suggests that passports were also issued to permit Japanese to leave Japan for purposes of work (see next section).

Passports changed after the start of the Meiji government in 1868. Even then, however, there were several names for such documents other than 旅券 (ryoken) or "passport" -- including the following, according to the robotic bureaucrat-cum-techie docent Archivo (アルチーボ), who helps Dr. Bunzō explain things to Clara.

印章 inshō "seal" [of permission]

通行免状 tsūkō menjō "passage permit"

海外証書 kaigai shōsho "overseas certificate"

海外旅行免状 kaigai ryokō menjō "overseas travel permit"

海外行免状 kaigai-yuki menjō "overseas-going permit"

Other sources also give 海外行御印章 (Kaigai-yuki go-inshō) or "overseas-going official-seal [of permission]" as a common term for what, from 1878, became 海外旅券 (kaigai ryoken).

Brochure-style passports (1878-1926)

The second part of the passport history exhibit shows passports of the kind that were printed on single folded sheets of paper.

There is a readable scan of the entire 12-page text of Japan's first passport regulations, called 海外旅券規則 (Kaigai ryoken kisoku) or "Overseas passport regulations", dated Meiji 11-2-20 or 20 February 1878. Hence 2 February is "Passport Day" in Japan.

The exhibit includes examples of a 1878 passport representing the earliest printed design. See the next section for an image and particulars.

The exhibit also shows examples of April 1893 and December 1905 revisions. Both examples provide information about the "head of household" (戸主 koshu).

The 1893 design was rather different. The example shown on the Bunzō site was used on 22 February 1895 to a "commoner" (平民 heimin) who was 27-year and 8-months old. He was being permitted to travel to "Hawai country" (布哇國 Hawaikoku) for "agricultural" (農策 nōsaku) purposes.

Security measures

As travel increased, so did the problem of forged passports. As a countermeasure, watermarks reading 日本帝国海外旅券 (Nippon Teikoku Kaigai Ryoken) and elaborate brown or green printed borders, were introduced from 1905.

An example is shown for such a passport issued on 8 May 1919 (Taisho 8) to a man born on 26 September 1873. The passport appears to specify that the man is bound for "Hawai" (布哇) -- apparently no longer "Hawai country" (布哇國), because in 1898 the United States had annexed it as a territory. The front page has a maroonish dark brown border

The 1911 and 1924 passports in my possession are of this design (see below).

Emigrants

This was not -- as Dr. Bunzō explains in a balloon to the travel-minded Clara -- an age for taking casual pleasure trips overseas, since travel by ship across vast oceans was arduous and time-consuming.

In time, passports were commonly issued to people who were recognized as "migrants" (移民 imin) emigrating from Japan to other countries. The first such emigrants were issued passports for the Kingdom of Hawaii, then nominally an independent country, in 1885.

Passports specifically for use by emigrants appeared from 1909. An example is shown of such a passport issued on 3 March 1911 to a Hiroshima-prefecture "commoner" (平民 heimin). The man's name is written below the term 移民 (imin), which has been printed in vermillion. He was 18 years and 6 months old.

Passport size

The passports had gotten smaller -- from a huge A3 size in 1878 to a smaller but still large (by present-day standards) B5 size from 1893. Clara is pleased to hear this -- but she worries that such small (?) pieces of paper could be lost. Not a problem, says Dr. Bunzō, because passports then, unlike today, were issued for one-time use only and became invalid if and when the bearer returned to Japan.

Photographs

The observant Clara wonders why she has not yet seen any photographs. Archivo explains that photos began to be attached from 1917 -- part of an international movement, he says.

Booklet-style passports (since 1926)

The third part of the passport history exhibit concerns the issue of newer booklet-style or "handbook-form" passports, which were introduced as a result of an international conference in Paris in 1920. Japan began using such passports from 1926.

The issuance of so-called "emigration passports" (移民用旅券) apparently ended, Dr. Bunzō says, because a number of countries had been refusing visas to people with emigration passports. By this the good doctor is probably alluding to the 1924 national-origin quota in the United States, which essentially excluded from immigration people from "Oriental" countries as racially unwelcome in the land of the free and the home of the brave.

The first booklet-style passport, designed in 1924, began to be used from 1926. This passport got at least a newer cover, with a differently designed chrysanthemum emblem, in 1938.

Both covers state 大日本帝國外國旅券 (Dai Nippon Teikoku Gaikoku Ryoken) or "Great Nippon Empire Foreign Country Travel Certificate" at the top, and show English "Passport of Japan" and French "Passeport du Japan" at the bottom, below and above the chrysanthemum emblem.

Sources

All passports shown on the above two Bunzō passport history exhibites are attributed to the Diplomatic Record Office of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan (外務省外交史料館) [DRO of MOFA].

The following article, apparently by a currator or researcher at this facility, is cited as a source of the explanations.

柳下宙子

戦前期の旅券の変遷

外交史料館報

第12号 (外務省外交史料館、1998)

Yanagishita Hiroko [Sorako?]

Senzenki no ryoken no hensen

[Changes in prewar passports]

Gaikō Shiryō Kan hō

[Bulletin of the Diplomatic Record Office of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan]

Number 12 (Diplomatic Record Office of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, 1998)

Construction of 1878-1926 passports

My own observations of the passports in my possession, issued in 1911 and 1924, are somewhat different.

Generally, it appears that all passports from 1878 to 1926 consisted of a single sheet of paper which was folded down the center with the crease on the left. Thus folded, they opened in the manner of a brochure that was published in a European language -- i.e., from left to right -- rather than in Japanese, which would be read from right to left. The A3 and B5 sheets folded into respectively A4 and B6 brochures. A4 is the most common larger "letter paper" size in Japan. B5 is most common smaller letter paper size. Both are also common sizes of magazines. A5 and B6 are common monthly magazine and book sizes, could be put in handbags or larger pockets.

The fronts of the 1878 and 1905 style brochure were in Japanese while the backs showed translations in other languages -- four from 1878 and two from 1905. Both sides of the 1893 passport brochure were in Japanese. Apparently foreign language translations were on the other side.

The inside of the brochure was used for visas and information related to transit, and for revenue stamps. And, from no later than 1917, a photograph was attached on the right side of the inside of the brochure, so as to be seen when opening the cover.

Seals on 1878-1926 passports

The vermillion seals on the cover pages of all three styles of this first series of passports were printed. These seals used the term 海外旅券 (kaigai ryoken) or "overseas passport" as follows.

|

旅 国 日 |

Nippon Tei- |

Nippon Em- |

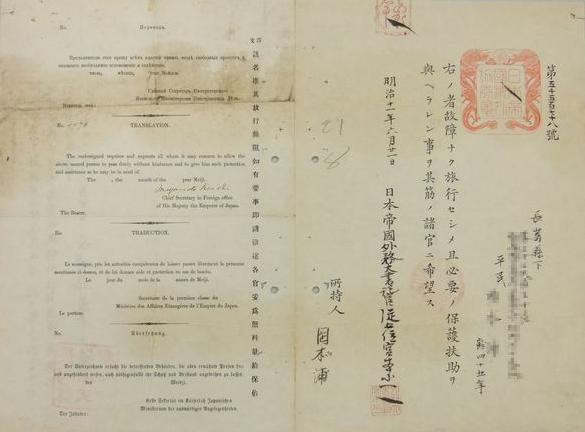

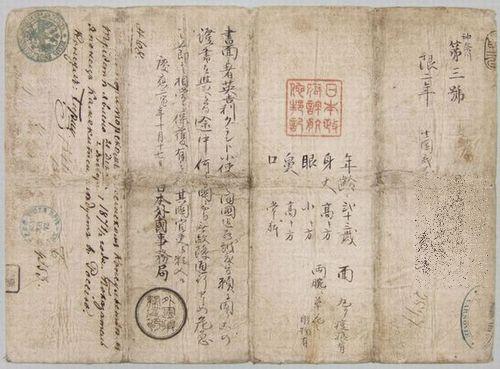

1866 Japan Foreign Office passport for Kanagawa servant of British subject

The earliest passports, issued in the late Tokugawa and early Meiji periods, were written mostly in hand, and their content seems to have varied according to their purpose. The two examples I have seen, though issued on the same date, and bearing the same seals, are visually very different.

Passport No. 1

The first passport was apparently issued on Keio 2-10-17 (23 November 1866) to an acrobat named Sumidagawa Namigorō (隅田川浪五郎), who is supposed to have led the "Nippon Imperial Troupe" (日本帝國一座) of performers to the 1867 Paris Exhibition via America.

According to a partial image I have seen, the passport was issued by the Japan Foreign Affairs [Bureau] (日本外國事務 [局]), apparently an office of the Foreign [Affairs] Magistrate (外国奉行) of the Tokugawa government in Edo. The seal below the name of the issuing office reads 外國事務局章 or "Foreign Affairs Bureau Seal". The seal suggests that the graph 局 should have been included in the name of the issuing office.

Passport No. 3

The third passport was issued on the same date, by the same office, and with the same seals, as shown and described below. This passport includes the graph 局 in the written name of the issuing authority, which corresponds to its name in the seal .

Number 3 was to a Kanagawa man for the purpose of accompanying a British subject as a servant. Kanagawa was the domain which included the port of Yokohama, which was opened in 1859, along with four outher ports, to foreign trade.

A large parcel of land was set aside as a settlement for foreigners. Foreign legations and other foreign organizations, and residences and other facilities for foreigners, were located there. Foreigners were generally restricted to the settlement, within which they had extraterritorial rights, under the laws of their own countries as enforced by their consulates and consular courts.

Many local people, however, were employed in the settlement by foreign organizations and individuals. Such settlements became venues for Japanese interest in foreign affairs to learn foreign languages and otherwise establish connections with outlanders.

Above 1866 Foreign Office passport

Above 1866 Foreign Office passportCompliments Bunzo, NA, DRO4 Right Front Japanese particulars Back English translation Click on images to enlarge |

|

The images to the right were copped from from ぶん蔵 (Bunzō), which attributes them to the Diplomatic Record Office of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Both images were compressed, and the bottom image was rotated to the right, as the page would have to be oriented in order to be read in English.

Construction

The document consists of a single sheet of thick washi paper measuring, according to Dr. Bunzō, 22.6 cm vertically by 31.8 cm horizontally. This was a little bit smaller than a sheet of ōban washi or, in present-day terms, a sheet of B4 paper.

The sheet was fold down the middle to make a roughly B5 brochure that opened the right, and down the middle again then once across, resulting in B7 pocket-size document that, of course, had to be unfolded to read.

Content

The front side had a physical description of the Kanagawa man on the right (front of the brochure). The diplomatic message in Japanese appeared on the left (back), followed by what appears to be a signed statement in another language, possibly English.

The back side had a complete translation of the Japanese on the outer page, meaning the physical description of the bearer and the diplomatic message. The translation is written so as to read the length of the sheet of paper when entirely unfolded.

Seal

The square vermillion seal on the first page reads as follows.

|

侘 府 日 |

Nippon Sei- |

Nippon Govern- |

Transcriptions

The following table shows transcriptions of part of the Japanese text on the front sice of the 1866 Number 3 passport and corresponding parts of the English translation on the other side.

The transcriptions were made from my own visual inspections of the rather small images of as posted on the Bunzō website of the National Archives of Japan. The transcriptions are partial as I was not able to clearly recognize all of the writing.

|

1866 Japan Foreign Office passport issued to Kanagawa servant of British subject |

|

|

Front side (right) |

Back side (top) |

|

神奈川 第三號 限二年 [未読] [未読] [亀吉] [未読]

年齡 弐十三歳

身丈 高キ方

眼 小キ方

鼻 高キ方

口 [未読]

面 丸ク痘痕有

[疱瘡?]

両腕ハ草花

彫物有

|

No. 3 Kanagawa Limited years 2 (Two) Birth place [unread] Name of the [bearer?] Kamekichi [unread]

Age 23

Stature Tall

Eyes Small

Nose high

Mouth [moustache?]

Face Round with

pock mark[s?]

On both [arms?] the [Flowers?]

[are?] tattooed

|

|

Front side (left) |

Back side (bottom) |

|

書面者英吉利クラント小使 ・・・[以降省略] 慶應二寅年十月十七日 日本外國事務局 [SEAL] (外國事務局章) |

This passport is supplied to the above mentioned person upon the request of Mr. Grant, a British subject, to have him accompany to England as Servant. 17th day of the 10th month of the 2nd year Keio [?] (Tora)

The Foreign Office

|

1878 Imperial Japanese passport for commoner

The 1878 passport I have seen was issued by the foreign minister of 日本帝國 (Nippon Teikoku) or "Empire of Japan" to a man described as a 平民 (heimin) or "commoner" in status. The translation page has boiler plate in four languages -- from top to bottom Russian, English, French, and German.

The Japanese text and the foreign language versions are very simple. The English section is completed.

1922 Japanese passport for Interior man (Shizoku)

I have seen a rough image of a 1914 passport, and I possess one 1922 and two 1924 passports. All three passports were of similar design.

Their covers, printed in the manner of a security document, are framed with an elaborately engraved guilloche border. The frame of the 1914 passport is green, while those of the 1922 and 1924 passports are a maroonish brown.

These passports were folded in the center to show the Japanese side as the front cover and the English and French side as the back cover. They were again folded in thirds. Folded like this, the passport could have been carried in a pocket, or first -- for better protection -- slipped into an envelope.

Judging from the passports in my possession, the other side or "inside" of such "brochure" passports had a small photograph of the bearer in the center of the right side. Free space on both the right and left sides was used for stamps and jottings of authorities when entering or leaving a country.

A small photograph, if pasted in the middle, would have escaped creasing. Taller photos, and smaller photos pasted higher on the page, were inevitably creased.

Additional pages and other related documents were inserted into the brochure by pasting them along the top or in a corner. Some such pages were hinged to the the top of back page with a pair of printed official seals.

These passports were called 日本帝國海外旅券 (Nippon Teikoku Kaigai Ryoken) in Japanese and "Imperial Japanese Government Passport" in English. Like the 1905 Korean passport, the foreign language translation page had only English and French. Apparently Russian and German had lost their status as passport languages in Japan.

1914 passport

I have seen a 1914 passport posted on a website called "Social studies photographs" (社会科の写真) created by Kimutoshi (/shakai/rekisi.htm). The attribution reads 函館北洋資料館 2005.2.19, presumably meaning that Kimutoshi took the photograph on 19 February 2005 at the Hakodate-shi Hokuyō Shiryō Kan" (函館市北洋資料館).

The elaborate frame is green. A vermillion stamp above the name of the bearer reads 移民 (imin) meaning "migrant" -- meaning, in this case, someone permitted to leave Japan for the purpose of settling overseas, hence an "emigrant".

The French part of the 1914 passport is completed. The image is not especially clear and I am unable to determine where the man was bound.

Kimutoshi remarks that the passport was issued to a person who "crossed [the sea] as a migrant" (移民として渡る人). He also observes, based on the first page, that the man was "5-shaku 1-sun tall" (身長五尺一寸) and an "older son" (長男), and that the Minister of Foreign Affairs at the time was Katō Takaaki (加藤高明).

Katō Takaaki (1860-1926) served as Japan's 16th, 19th, 26th, and 28th foreign ministers in 1900-1901, 1906, 1913, and 1914-1915. He was Japan's 24th prime minister, serving year, from 11 June 1924 to 28 January 1926, at the end of the Taisho period.

1922 passport

This passport, in my possession, was issued on 27 May 1922 to a man who was both a head of household (戸主 koshu) and a descendant of a former samurai by household registration status (士族 shizoku).

The man was born on 22 June 1888, hence was one month short of his 34th birthday when he received the passport -- in Germany. The passport was issued by a Japanese plenipotentiary, apparently to replace another passport. The passport authorized the bearer to gravel to all Euroamerican countries (欧米各国 Ōbei kakukoku) for medical research.

The passport bears the five-digit number 27524. Small characters printed in the center of the bottom part of the decorative frame on the first page translate "Produced by the Printing Bureau August 1905".

To be continued.

1924 Japanese passports for Interior man and family

I have two passports issued in Japan to a man and his wife on 23 April 1924. The passports bear successive six-digit numbers 549306 and 549307.

The passports were issued in Osaka prefecture to a medical doctor and researcher, Yamaguchi Sachu, and his accompanying wife, Yamaguchi Ikuko.

The first numbered passport describes Yamaguchi Sachu as "adopted son-in-law" (婿養子 mukoyōshi) of the head of household (戸主 koshu) of his household register of record. The second numbered passport describes Yamaguchi Ikuko as "the wife of the adopted son-in-law" (婿養子ノ妻 mukoyōshi no tsuma) of the same head of household. Presumably Ikuku was the household head's daughter.

The passports allow their bearers to travel to or through a long list of territories, cities, and countries, accompanied by his wife. The particlars are hand-written in Japanese on the Japanese side, and typed in both English and French on the translation side.

The English particulars for Yamaguchi Sachu's passport read as follows. I have spaced the information, and justified everything to the right, for convenience in reading. All information that has been typed into the printed form is underscored.

|

Yamaguchi Ikuko's passport describes her as "Mrs. Ikuko Yamaguchi, age 20 years full." Other particulars are the same.

The Japanese side of Yamaguchi Sachu's passport states that the purpose of his travel is "medical research and observation". The purpose of Yamaguchi Ikuo's travel is given as "accompanying her husband". These purposes are not stated on the translation sides.

Baby born in Germany

Ikuko was 13 years younger than Sachu. It is not clear how long they had been married. Of considerable interest is the fact that Ikuko gave birth to a child while on their journey.

The child's passport was attached in the form of a single sheet of paper with a photograph, sealed into Ikuko's passport, by the Consul general of Japan in Hamburg on 18 August 1925. Presumably the child was born in Germany.

The child appears to be only a few weeks, at most a few months, old. Its date of birth, sex, name, and other particulars are not stated.

The inserted sheet is headed "Kaiserlich Japanisches / Generalkonsulat / Hamburg" and states in English that "This passport is good for United States of America and Hawaii".

The stamps authenticating both the photograph, and the objectives of the passport, are seals of the "Kaiserlich Japanisches / General-Konsulat / Hamburg" with corresponding Chinese characters.

The light blue printed seals which secure the pages attached to Sachu's and Ikuko's passports read "Services Diplomatiques et Consulaires / Japon" in French around the outside, and 日本帝國 / 在外公館 in Sino-Japanese. In English, the French means "Diplomatic and Counsular Services / Japan" and the Sino-Japanesse means "Japan empire / Resident-abroad government-office" -- i.e., "Overseas [diplomatic] agency".

To be continued.

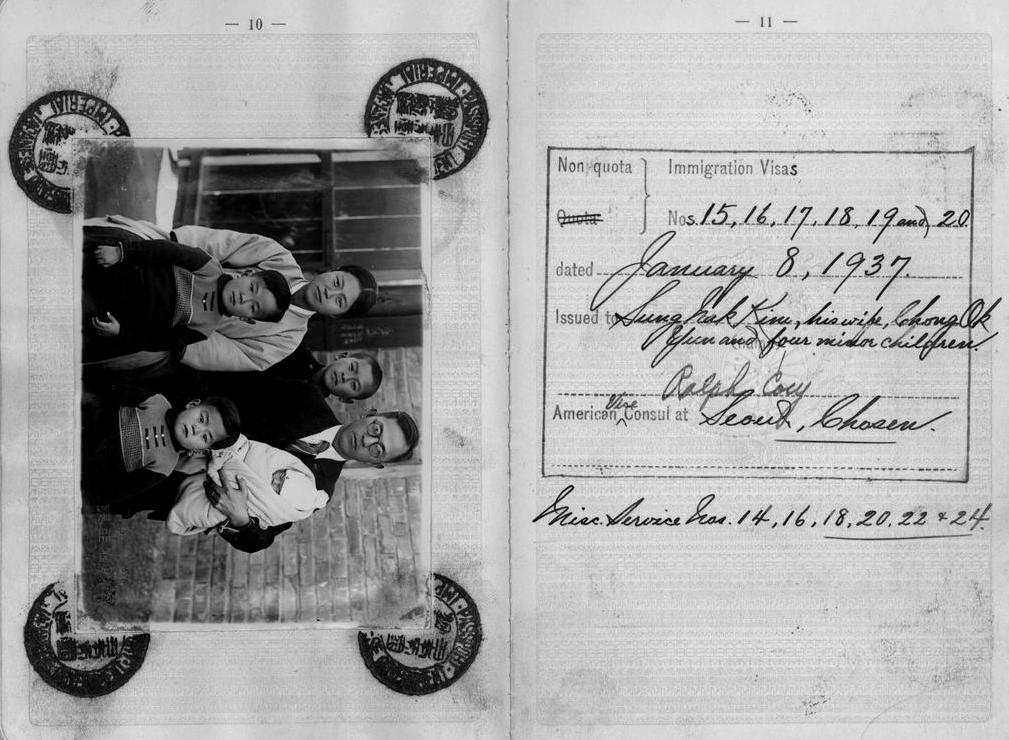

Circa 1937 Japanese passport for Chosen Japanese and family

From 1926, passports were issued as booklet of the kind familiar today, though of somewhat different size.

The example shown here was issued to a Japanese man of Chosen terriotiral affiliation and his family, namely his wife and four children, to facilitate their emigration from Chosen, Japan to the United States as non-quota immigrants.

Since Chosen was part of Japan, people affiliated with Chosen through population registers were Japanese. As such they were issued Japanese passports for purposes of emigrating from Japan.

Shown here are pages 10-11 of a passport issued by the Imperial Government of Japan no later than 8 January 1937, the date of a visa issued by a Vice Consul at the American Consulate in Seoul, Chosen. The passport itself was probably issued the previous year.

For a look at the passport bearer's Immigrant Identification Card, also issued by the American Consulate in Seoul, on the same day and by the same consul, see 1937 US Immigrant Identification Card below.

Here I will explain the significance of both pages -- Page 10, which shows a photograph of the bearer and his family, the Page 11, which show a US visa stamp and immigration particulars.

Family photograph (Page 10

The photograph has been attached to the page by the issuing country in a manner that was fairly common throughout the world at the time -- with an official seal in each corner. The seals made it difficult to change the photograph. The seals used to protect the authenticity of the photograph on this passport appear to be simply impressed rather than embossed, which would have required dies.

In the center of the seal are two columns of highly stylized Chinese characters that, while blured, appear to read 日本帝國 / 海外旅券 (Nippon Teikoku / Kaigai Ryōken), meaning "Nippon empire / Overseas passport. Top and center of the seal, in the concentric ring around the characters, is "・PASSPORT・". Running counterclockwise from this -- down the left, across the bottom, and up the right of the ring -- is "IMPERIAL JAPANESE GOVERNMENT".

US immigrant visa stamp (Page 11)

There is also an image of a stamp dated 8 Janauary 1937 in the Japanese passport of the person who was issued the above immigrant identification card. The stamp is for six numbered immigration visas -- one for the passport bearer, the others for his wife and four minor children.

"Quota" is crossed out leaving "Non-quota" as the visa category, which corresponds to the status provided on the identification card. The stamp is signed by the same American Vice Counsul at "Seoul, Chosen" who signed the identification card. The visas were issued in "Seoul, Chosen" -- which, like particulars entered on the visa stamp, have been penned in hand.

Because the United States recognized Chosen as part of Japan, it considered subjects of Chosen as Japanese. Under contemporary national-origin quota rules, Japanese would not ordinarily not have been admissible to the United States as quota immigrants. However, there also provisions for admitting aliens as non-quota immigrants.

For a fuller discussion of the implications of "non-quota" and the identity of Sung Nak Kim, see 1937 US Immigrant Identification Card below.

|

Circa 1937 Imperial Japanese passport issued to Chosen Japanese man and family |

||||||||||||

|

The following image was copped and cropped from Kushibo's Monster Island! blog. |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

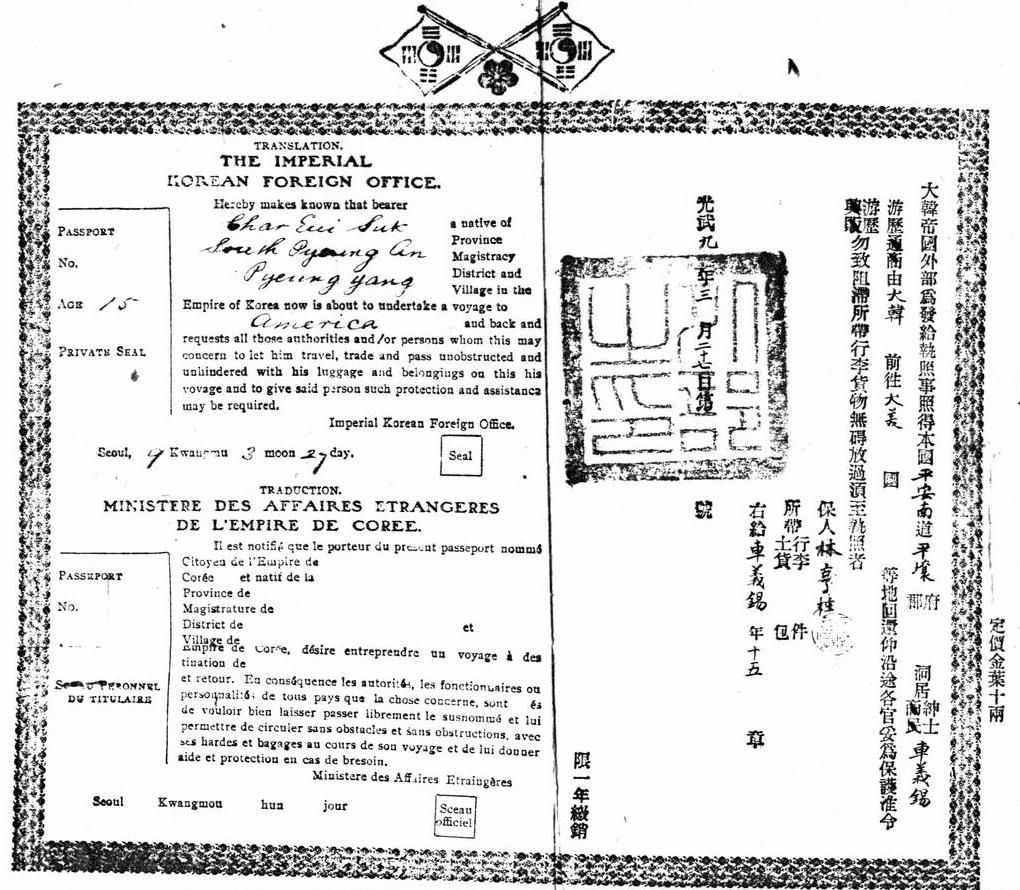

Imperial Korean passports

I have not personally collected passports or other travel documents related to Korea or Chosen. I have, however, examined the image of a 1905 Korean passport posted by someone who goes by the handle of Kushibo and has a blog called Monster Island! (actually a peninsula).

The image of the passport is featured on a blog article called "Korea vs Corea". I first stumbled onto the article a few years, before it was incorporated into the present "Monster Island!" blog.

The purpose of the article is to dispute the popular view that "Corea" is the proper term for the country that Japan began to spell "Korea" in order that it come below Japan in alphabetic listings.

While Kushibo is to be credited with bringing together a variety of artifacts that undermine the "C" to "K" conspiracy theory, he is stronger on "show" than "tell", as his descriptions of some of the artifacts are incorrect or misleading. Despite these shortcomings, his article is recommended reading.

Kushibo, who I take to be male, describes himself as a "forean" who has strong interests in all manner of Korean affairs. He appears to be a native speaker of English, and from his self-introduction he is fluent if not bilingual in Korean. He also claims to have some proficiency in Japanese.

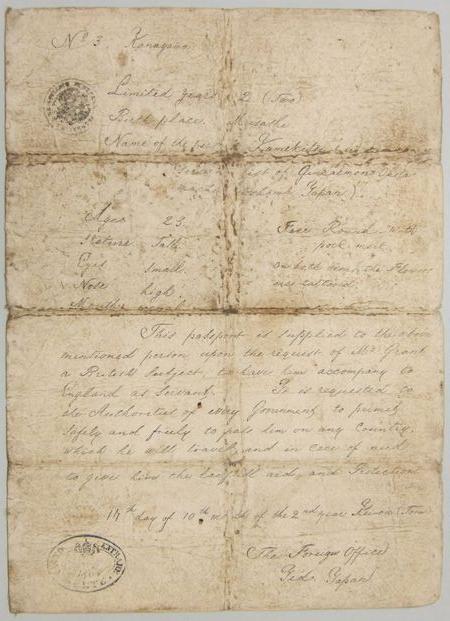

1905 Imperial Korean passport

The passport shown here was issued by the Imperial Korean Foreign Office in Seoul on the 27th day of the 3rd month of the 9th year of 光武 (E Kwangmu, F Kwangmon). As a solar date it would be 27 March 1905. As a lunar date it would be a day in April or May.

The "data page" to the right is in Chinese. The "message page" to the left is in English and French.

The name of the issuing country is 大韓帝國, which in the formally printed English and French translations is rendered "the Empire of Korea" and "l'Empire de Corée".

The name of the bearer was Char Eui Suk, a "gentleman" (紳士) rather than "merchant" (商民), who was traveling to "America" for "travel" (遊歴) rather than "trade" (通商). He is said to have been 15 years of age, which may represent a count of one year at the time he was born.

The English describes the bearer as "a native of [locality] in the Empire of Korea" whereas the French says he is a "Citoyen de l'Empire de Corée et natif de la [locality]". The corresponding Sinific term for "native / natif" is 居 meaning "residing" or "domiciled" in the noted province, city or district, and village.

The passport was valid for one year.

Design

The 1905 passport appears to be designed in the same manner as Japanese passports at the time, which of course were designed in the manner of passports in many other countries.

The certificate was folded down the center to make a brochure with the right side as the front cover. A photograph was probably attached to back of left side. Visa and other information stamped or written at various points in transit would also have been on the other side.

Period

The passport was issued during the Russo-Japanese War.

In 1904, shortly after the war began, Korea had become a protectorate of Japan. Japan had long been involved in governmental reforms in Korea, and Korea had adopted a number of Japanese administrative methods.

By the end of 1905, within months after the war, Korea had desigated Japan as its proxy in foreign affairs, which meant that Japan oversaw matters the issuing of passports to Koreans and visas to aliens coming to Korea.

|

1905 Imperial Korean passport issued to a "gentleman" |

||||||

|

The following image was copped and cropped from Kushibo's Monster Island! blog. |

||||||

|

||||||

Imperial Manchou national handbooks

Toward the end of World War II, in order to control labor migration within Manchoukuo, the Imperial Manchou government issued national handbooks to many of its subjects, complete with photographs and fingerprints to discourage identity changing or switching.

For an account of such handbooks, and images of two different kinds of handbooks with translations, see Manchoukuo national handbooks in the "Fingerprinting in Manchuria" section of the "Fingerprinting" feature of this website.

Of the two handbooks shown here, one uses the term "race" (人種) as the classification, while the other uses the term "ethnonational category" (民族之類).

1945 Manchoukuo handbook (Mongol cultivator, 29 pages)

For images and translations of an 8-page foldout national handbook issued by the Government of the Empire of Manchou on 1 February 1945 to a male cultivator of the Mongol "race", see 29-page Manchoukuo national handbook in the "Fingerprinting in Manchuria" section of the "Fingerprinting" feature of this website.

1945 Manchoukuo handbook (Han farmer, 8 pages)

For images and translations of an 8-page foldout national handbook issued by the Government of the Empire of Manchou on 1 April 1945 to a male farmer of the Han "ethnonational category", see 8-page Manchoukuo national handbook in the "Fingerprinting in Manchuria" section of the "Fingerprinting" feature of this website.

US immigration documents

Forthcoming.

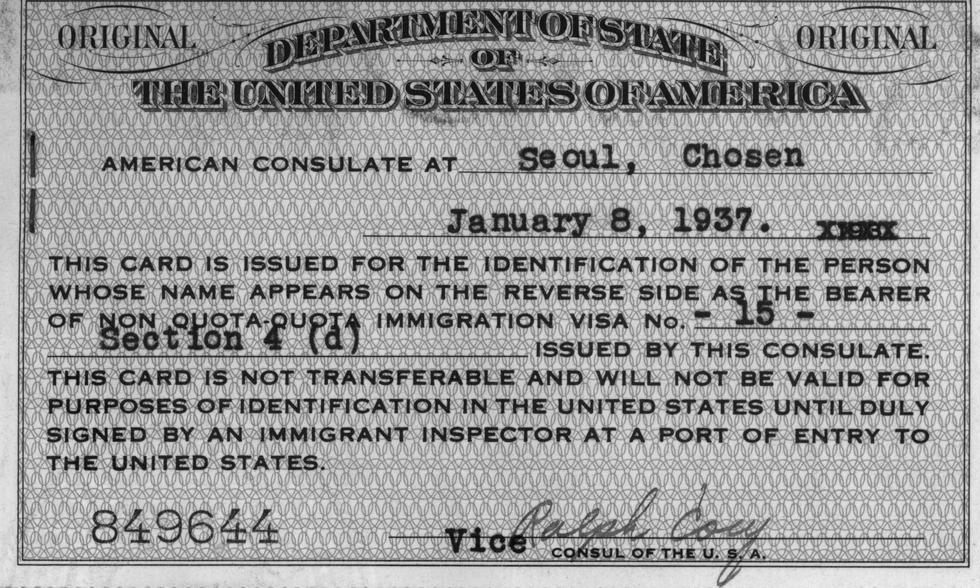

1937 US Immigrant Identification Card for Japanese man from Chosen

Unlike many countries in the world, the United States permitted immigration from abroad -- meaning entry to the US for purposes of taking up permanent reisdence. American consulates therefore issued immigrant visas in accordance with a variety of immigration laws.

Since the United States had recognized Japan's annexation of Korea as Chosen, and accepted the conditions that Japan placed on foreign legations in Chosen, the American Consulate in Seoul, as it called itself, issued visas to Japanese subjects in Chosen who had cause for travel to the United States. This included immigrant visas.

The national-quota system introduced in 1924 essentially excluded aliens originating from Asian countries. However, immigration was possible under provisions for non-quota immigration.

The Immigrant Identification Card shown here was issued by the American Consulate in Seoul to Sung Nak Kim. According to the card, Kim was born in Chosen and was of Japanese nationality.

Kim was issued card to facilitate the non-quota immigrant visas the same American consulate had granted him, his wife, and four children. The visas were entered in a family passport issued by the Imperial Government of Japan. For a look at the passport photograph of the family and the visa, see 1937 Imperial Japanese Passport above.

Two sides of identification card

The first side of the US immigration card represents the issuing authority, namely the American Consulate in Seoul, which was under the Department of State. It states only the legal authority -- the visa number, and the classification of the visa according to the section, paragraph, and clause of the immigration law -- for issuing the visa to the person identified on the other side.

The second side of the card represents the Department of Labor, which oversaw the administration of non-quota visas. This side of the card also states the status of admission in terms of the section, paragraph, and clasue of the immigration law.

1937 immigration from Chosen to the United States

Kushibo also shows two items related to a Japanese man of Chosen status who was issued an immigrant visa to the United States in 1937 -- an immigrant identification card and an immigrant visa.

Kushibo calls the card a "1937 'green card' (U.S. alien registration card) of Japanese national listing Chosen as country of birth". Metaphorically it might be a "green card" but it is certainly not an "alien registration card". As presented, it is merely an "Immigrant Identification Card".

|

1937 US Immigrant Identification Card issued in Seoul, Chosen to Sung Nak Kim, Japanese |

||||||

|

The following image was copped and cropped from Kushibo's Monster Island! blog. |

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

Linda Shin on Sung-nak Kim

Who, though, was Sung-nak Kim?

He appears to have been a Christian minister -- hence he and his family qualified for a non-quota visa.

His name crops up in some English sources in the United States.

I've been a subscriber to Amerasia Journal since its start in 1971. The third issue includes the following article by Linda Shin.

Linda Shin

Koreans In America, 1903-1945

Amerasia Journal (UCLA Asian American Studies Center Press)

Volume 1, Number 3, November 1971

Pages 32-39

In the penultimate paragraph, immediately after she claims that "Koreans [in America] unanimously supported the move to intern Japanese-Americans during the war and in other ways declared their allegiance to the Allied cause" (page 37), Shin makes this observation (page 37, and page 39 note 33).

|

In spite of their aspirations, Koreans in the United States found themsleves largely frustrated by the postwar solutions worked out by the great powers. At the Potsdam Conference, it was decided to divide Korea at the thirty-eighth parallel, with the Americans Military Government ruling the southern sector only. As Syngman Rhee began to rise to power within the American sector, those who were not part of his organization in the United States found themselves alienated. A fifteen-man delegation of Koreans from America to Korea in the post-war period was forced to leave when it found itself frozen out by Rhee and the American military authorities. [Note 33] Hence the division of Korea and Rhee's assumption of power in the South, together with the cultural dislocation felt by some Koreans after their long years in America, worked to alienate Koreans from America in Korea and provide for their continued residence in the United States. Thus, many Koreans found themselves doubly exiled. 33. Interview with Reverend Sung-nak Kim, Fall, 1969. |

Korean-American Oral History Project

The following item is listed on page 4 of a 5-page PDF file served by the Online Archieve of California (OAC). The file is called "A Finding Aid for the Korean-American Oral History Project, 1970-1979" and relates to Collection No. 1414, UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections, Manuscript Division.

Box 1 15A, 15B no.57 Rev. Sung-Nak Kim.

Physical Description: [Recording is in] Korean.

An abstract describes the project, conducted through the Asian American Studies Center UCLA, as follows (retrieved 10 December 2009).

Abstract: The Korean-American Oral History Project at the UCLA Asian American Studies Center was founded to develop oral history source materials on Korean American history during the 1903-45 period, and to facilitate their use by researchers. The tape-recorded oral histories of Korean American immigrants to the United States made by Sonia Shinn Sunoo form a part of that project. The collection consists of 31 cassette tape recordings of interviews with Korean immigrants to the United States.

Sonia Shinn Sunno is said to have gifted the tapes in 1985.