Fingerprinting in Manchuria

Before and during the tenancy of Manchoukuo

By William Wetherall

First posted 1 August 2007

Last updated 15 December 2009

Manchuria and Manchoukuo

•

1924 South Manchuria Railway

•

Jo Suichin on Manchuria

•

Tanaka Hiroshi on Fushun coal mines

•

Fushun prison and war criminals

•

Pingdingshan incident

•

Wang Hong Yan on coolies in Manchoukuo

•

Excerpts from SMR progress reports

•

1939 Special Kenpeitai

•

Puppet Palace Museum

•

Sources

Manchoukuo national handbooks

1945 29-page handbook

•

1945 8-page handbook

•

National precepts

•

9.18 History Museum

Fingerprinting in Manchuria and Manchoukuo

Fingerprinting was carried out by various Japanese authorities in parts of Manchuria under Japanese control from as early as 1924 for the purpose of labor management. Fingerprinting related to control of labor migration, and as a countermeasure to subversive activities, spread after 1932 when Manchuria became Manchoukuo, an independent state largely created by, and tethered to, Japan.

The South Manchuria Railway Company, which had jurisdiction in Railway Zones and in mines and other industrial facilities operated by this government corporation, adopted fingerprinting in 1924 as a means of controlling its employees. Later, Manchoukuo also adopted fingerprinting to discourage unpermitted migration at a time when there were labor shortages in critical industries.

Police maintained by the military and civilian governments of the Kwantung leased territory, and the gendarme (kenpei, military police) units of the Kwantung Army in Manchuria and later Manchoukuo, fingerprinted some people in their efforts to deal with both banditry and subversion. The Special Kenpeitai established in the Manchoukuo capital of Hsinking in 1939 had a fingerprint unit to facilitate identification in its anti-subversive operations.

Prison wardens and police in Manchuria also took fingerprints of prisoners and suspects. Manchoukuo's national police forces included the Metropolitan Police Board at Hsinking and provincial police forces under provincial governors.

Nationals of Manchoukuo were also fingerprinted for identification purposes in handbooks issued to nationals from 1945.

1924 South Manchuria Railway Company

In 1987, on the eve the first major revision of the Alien Registration Law since its enforcement from 1952, Tanaka Hiroshi published the first article to link the fingerprinting provisions that came into effect from 1955 with practices that began in Japanese companies in Manchuria as early as 1924.

|

On 18 September a bill to revise the Alien Registration Law passed the extraordinary [session of the] Diet. When you think that on this day, 56 years ago, the "Manchurian Incident" began, you cannot help but feel the irony of history. For former "Manchoukuo", which Japan created with the "Manchurian Incident", is the place of origin of the fingerprint impression system that is the object of this revision bill. |

Tanaka, then a professor at Aichi Universiety, noted that the preceding year, prime minister Nakasone Yasuhiro had returned from a state visit to the Republic of Korea and, according to a young researcher familiar with the history of the Fushun coal mines, Japanese authories first took fingerprints in 1924, for the purpose of controlling workers at the Fushun mines of the South Manchuria Railway Company (Tanaka 1987, page 21-22).

Tanaka had gone to China with eighteen others concerned with the fingerpring system -- including researchers, attorneys, and civil movement persons the South Manchuria Railway Company (南満州鉄道株式会社) carried out fingerprinting for the purose of controlling laborers coal mines in Fushun coal mines (撫順) in Manchuria, east of Mukden (奉天 Fengtien, now Shenyang 陳陽), around 1924 .

Jo Suichin on Manchuria

Jo Suichin

Attention is drawn to the quotation from Jo Suichin (徐翠珍 Jo Sui Chin), who is referred to as a "Chinese" (中国人) born in Japan. Her nationality is not clear from what has been published about her.

The following Kyodo story ran in the English language press in Japan at the height of the anti-fingerprinting movement in 1987. It is probably a translation of an article that appeared in local papers in Japanese. I have transcribed it from a facsimile of a clipping that was reproduced in an anti-fingerprint movement newletter.

Kawakubo Kimio (川久保公夫), a professor of European economic history, but also a student of Taiwan and Chosen under Japanese rule, passed away in 2002 at the age of 82. An obituary in 台湾月報, which features abstracts of newspaper articles in ROC newspapers, called him "a friend of Taiwanese human rights" (台湾人権之友).

|

Fingerprinting in Manchoukuo (Mainichi Daily News, 12 August 1987) |

|

Fingerprinting Existed In Beijing (Kyodo) -- Fingerprinting as required under Japan's Alien Registration Law dates back to pre-World War II days to Manchukuo, a puppet state established by the Japanese military in 1931, according to a Japanese survey team. Kimio Kawakubo, vice president of the Osaka University of Economics and Law, told reporters this was discovered when his team carried out a survey in an area of northeastern China formerly known as Manchukuo. Kawakubo said his team had met about 20 people in northeastern cities in Liaoning and Jilin provinces, including Shenyang and Fushun. He said some Koreans in Manchukuo were unable to enter elementary school because they refused to be fingerprinted and some Chinese were also punished for refusing. Manchukuo's security division established the Fingerprinting Administration Bureau and the way it administered alien fingerprinting is similar to the methods used by the Japanese government today, Kawakubo said. Hiroshi Tanaka, a member of the team and a professor of Aichi Prefectural University, said the Manchukuo administration introduced the fingerprinting system to prevent laborers from fleeing and anti-Manchukuo elements from entering the area. |

Some of the generalities in the above article are a bit misleading. Fingerprinting in greater Manchuria, including Manchoukuo, was carried out by more than one agency, at different times, in different regions, and for a variety of reasons. These agencies included the South Manchuria Railway Company, the Special Kenpeitai, and the government of Manchoukuo.

Nationals of Manchoukuo were also subject to fingerprinting in "national handbooks" issued by the government.

Tanaka Hiroshi on Fushun coal mines

Tanaka on Fushun coal mines

Tanaka Hiroshi reported in 1987 that the South Manchuria Railway Company (南満州鉄道株式会社) fingerprinted Chinese, Chosenese, and others in connection with labor management at coal mines in Fushun coal mines (撫順) in Manchuria, east of Mukden (奉天 Fengtien, now Shenyang 陳陽), around 1924 (Tanaka 1987, page 21-22).

In addition to building and running railways, South Manchuria Railway operated what is now -- in the People's Republic of China -- the world's largest open pit coal mines. SMR also operated iron works and other industries within reach of its tracks.

Tanaka reported that he interviewed five former employees of the Fushun coal mine, all Chinese from Shantung (山東) peninsula. One testified that the Japanese army blocked both ends of the road through his village, rounded up healthy men, and placed them in a concentration facility (集中営). On the way to Fushun by boat and train, the men were handcuffed in pairs to prevent them from escaping.

The men were fingerprinted first at the concentration facility, then again at the mine where they were deployed. The work was hard, the life miserable, and men would run off. If captured, their prints would be matched and they would be returned to the mine and tortured.

Tanaka does not state when this was supposed to have happened. Presumably it was after 1937, when Japan occupied the peninsula.

Tanaka wrote that fingerprints were impressed when workers received wages. According to South Manchuria Railway materials he does not identify, fingerprints were also used at time of employment.

Tanaka reported some interesting figures about the use of fingerprinting when screening potential employees. According to a fiscal 1937 report in the same materials, those found to be unqualified for employement included 1,022 who had reapplied for employment before two months had passed since they had been laid off, and 304 who had been laid off for bad conduct. Twenty-five percent of the unqualified applicants were discovered through an examination of their fingerprints (ibid, page 22).

Fingerprinting spread from their introduction in 1924, according to Tanaka. Another early example of their use, he wrote, was to deal Chinese employees of the Manchuria-Mongolia Wool Weaving Company (満蒙毛織株式会社) at Fengtien also (Mukden, Shenyang) who went on strike in October 1926.

Tanaka observed that several labor mobilization and control laws in Manchuria in 1938 and 1939 resulted in the fingerprinting of all ten fingers on labor cards (労働票) which served as identification documents. These laws were (ordinance details according to Wang 2000): (1) State General Mobilization Law (国家総動員法), Imperial Ordinance No. 19 of February 1938; (2) Labor Control Law (労働統制法), Imperial Ordinance No. 268 of December 1938; and (3) Vocational Capacity Registration Order (職能登録令), Imperial Ordinance No. 232 of September 1939.

Fushun prison and war criminals

In 1936, Japan built a prison at Fushun (撫順典獄). By November 1945 the facility was taken over by Soviet forces, and was under communist Chinese control until March 1946 when nationalist Chinese forces took Shenyang. The nationalists put communist party members and other anti-Kuomintang elements in the facility and renamed it "Liaoning Prison No. 4" (遼寧第四監獄). In November 1948 the communists regained control of Shenyang and renamed the Fushun prison "Liaoning Prison No. 3" (遼寧省第三監獄).

In 1950, the year after the founding of the People's Republic of China, the facility was renamed "Lushun War Criminal Administrative Office" (旅順戦犯管理所). It had about 1,300 inmates, consisting of war criminals from the Japanese, Manchoukuo, and KMT armies.

In 1950, the Soviet Union transferred some 1,062 Japanese prisoners it had sent to Siberia in 1945 to the People's Republic of China as a gesture of USSR-PRC friendship. PRC placed the men in war prisoner administrative offices. Some 969 of them ended up in the Fushun War Criminal Administrative Office (撫順戦犯管理所), aka "Fushun War Criminals Administrative Center".

About eighty percent the Japanese prisoners handed over to PRC were military personel. The rest were bureaucrats and police officers. The Soviets had sent about 60,000 Japanese POWs to Siberia in 1945. Most of those who survived the ordeal had been repatriated to Japan by 1949.

In October 1950, during the Korean War, the prisoners were moved to Harbin and divided between two facilities, higher ranks in one, lower ranks in another. After the war reached a stalemate the following year, some 669 non-commissioned officers were returned to Fushun after the war reached a stalemate. Re-education began in earnest from 1952.

Military tribunals were held in 1956. Most of the Japanese inmates were repatriated to Japan that year. Some 45 were found guilty but the maximum sentence was twenty years. Former Japanese inmates have claimed -- in what has been called "the miracle of Fushun" -- that were well treated and, in time, recognized their offenses against Chinese and repented. Doubters claim they were brainwashed.

Soviet occupiers also sent the last emperor Pu Yi (1906-1967), and a few Manchurian generals who had collaborated with Japan, not to Siberia but to a spa near Khabarovsk, very close to the border with Manchurian China and home as it were. Pu Yi, and the generals, were turned over to PRC in 1950 and placed in the Fushun facility.

Pu Yi underwent ten years of re-education -- and also experienced the miracle of conversion "from devil to human being" -- before his release to live in Beijing in 1959.

The Fushun facility was closed in 1986 and turned into a historical museum. In 1988, some members of the "Association [liaison committee, network] of returnees from China" (中国帰還者連絡会) or "Tyuukiren" (中帰連 Chūkiren), an organization founded in 1957 by former Fushun inmates, sponsored the construction of the "Monument of apology to the martyrs who died resisting Japan" (向抗日殉難烈士謝罪碑) at the site.

Chukiren's members have been very active in promoting their essentially PRC view of the history of Sino-Japanese relations. They are also the objects of deconstruction by historians who claim the men were brainwashed to brainwash other Japanese upon their release and return.

The civil war in Manchuria

When passing control of Manchuria over to Republican China in later handed after as part of the Allied Forces and handed about one-thousand Japanese POWs allegedly involved in war crimes to the communist government of China after Chinese military tribunals tried 517 Japanese as B-class and C-class war criminals. All but 59 were convicted. 148 were executed. 23 (48 percent) of the 48 tried in Shenyang were executed, compared with 46 (39 percent) of the 118 tried in Guangdong and 31 (40 percent) of the 78 tried in Beijing.

The Soviet army invaded Japanese outposts in Manchuria shortly after midnight of 8 August 1945 -- i.e., early on the morning of 9 August -- a few days before Hirohito accepted the terms of the Potsdam Declaration and ordered Japanese forces to cease fire. The Soviet Union accepted the surrender of Japan in Manchuria -- including the surrender of the Manchoukuo government -- under the terms of the Instrument of Surrender signed in Tokyo on 2 September 1945 and General Order No. 1 issued the same day.

Within months of Japan's surrender, Manchuria had become a battleground for communist and nationalist armies contending for control of the region.

The USSR withdrew its occupation forces from Manchuria in March and April 1946. The Soviets moved dismantled Japanese factories to Siberia and left Japanese military equipment to communist Chinese forces concenterated in Inner Mongolia and northern Manchuria.

As Soviet forces withdrew from the south, Republic of China forces moved north into the region along railways and roads from Beijing (Peking) and Tianjin (Tientsin), and from Dalian (Talien). The nationalists take Shenyang (Mukden, Fengtien) from communist forces then lose Changchun (Hsinking) further north. Then the communists take Harbin and withdraw from Changchun. A shakey truce, along a line south of Harbin, endures for several months.

In the meantime, nationalist forces are spread too thin throughout northerneastern China, while communist forces have absorbed elements of the Manchoukuo army. Both sides break the truce, and U.S. trucemaster General George Marshall orders an end to American support of either side. U.S. Marines withdraw from Manchuria in September 1946.

Communist forces, stronger with defections after victories elsewhere in northeast China, push south from Harbin, bent on taking all of Manchuria. By September 1948 the nationalists have withdrawn from Changchun. By November Shenyang has fallen to the communists, who by December control the entirety of what had been Manchoukuo and the Kwantung Leased Territory, where the USSR would retain rights in Port Arthur until 1955.

Peking falls in January 1949. The People's Republic of China, founded on 21 September, formally takes its first breath on 1 October. The nationalist capital, which had moved from Chongqing (Chungking) to Nanjing (Nanking), then back to Chongqing, is forced to flee to Chengdu (Ch'engtu).

By December 1949, the Chengdu captial is abandoned by remnants of the government of the Republic of China, which completes its evacuation to the province of Taiwan, retaining control of the Fukien province islands of Matsu, Quemoy, and Tachen in the wake of its escape.

Pingdingshan incident

A village at the foot of Pingdingshan (平頂山) in Fushun was the scene of what some historians allege to have been a massacre of over 3,000 Fushun miners and others by Japanese Imperial Army troops on 16 September 1932.

There is now a large memorial on the site, completed in 1972 on the fortieth anniversity of the incident. The main hall covers a 5-by-80 meter grave excavated in 1970. Hundreds of skeletons are strewn in the strip.

More realistic estimates run from 400 to 800 dead and wounded in retaliation against raids on Japanese facilities and military personnel by guerrillas and bandits on the first anniversary of the Manchurian incident which precipitated the establishment of Manchoukuo that spring.

Pingdingshan redress lawsuits

In 2002, the Tokyo District Court recognized that the incident at Pingdingshan resulted in tragic deaths. However, it rejected the claims by survivors seeking redress, in view of the fact that first ROC in a treaty with Japan in 1952, and then PRC in a joint communique with Japan in 1972, had agreed that issues of compensation for acts by Japan in China were settled.

Courts have generally regarded these settlements as tantamount to the party states abandoning the rights of their nationals to demand reparation. The Tokyo High Court confirmed the lower court's ruling in 2005, and the Supreme Court rejected the final appeal by the survivors in 2006.

Wang Hong Yan on coolies in Manchoukuo

Wang on coolies and fingerprinting in Manchoukuo

1937, the fifth-year anniversary of the founding of Manchoukuo, was taken as an occasion for making sweeping administrative overhauls to facilitate the next five years of development. The year was punctuated by the so-called "China Incident" of 7 July 1937, which precipitated the start of what China considered a war with Japan. The year ended with fall of Shanghai and Nanking in the Republic of China -- and, in Manchoukuo, the nominal end of extraterritoriality with the transfer of properties and the Kwantung Bureau, the Japanese Embassy, the Chosen Government General, and the South Manchuria Railway Company (including the Railway Zones and other SMR properties) to Manchoukuo jurisdiction.

Wang Hong Yan, one of Tanaka Hiroshi's students, made several observations about labor issues in Manchoukuo in a doctoral dissertation (Wang 2000).

Wang writes that the implementation of a five-year development plan in Manchuria in 1937 led Japan to expand immigration of coolie labor, thus reversing its recent attempts to limit the entrance of migrant laborers from China. By 1940 some 1.3 million new migrants had come into Manchuria, he says.

However, because of limitations on how much money Chinese could send back to their families, and labor supply and demand factors in China and Mongolia, the influx of coolie labor into Manchuria dropped to about 920,000 by 1941. Soaring prices, lower wages, and high mobility rates led to the implementation of fingerprinting, beginning at the Fushun collieries, as a measure for prohibiting labor migration. However, Wang says, labor shortages, especially at the coal mines, were severe.

Excerpts from SMR progress reports

Excerpts on Manchuria labor migration from SMR reports

Some of the most dynamic, if somewhat propagandist, accounts of labor migration in greater Manchuria are found in the six volumes of the "Progress in Manchuria" reports published in English by the South Manchuria Raiway Company between 1929 and 1939.

See Manchuria reports: Building a model railroad for an overview of all six reports.

The first Report on Progress in Manchuria, 1907-1928 (The South Manchuria Railway, Dairen, March, 1929) makes this observation in connection with migration into Manchuria (page 13).

|

Of the immigrants arriving during the 1922-25 period, 50 per cent. or more, according to statistics taken at Dairen, where such estimates are most accurate, were merely seasonal labourers who returned to their homes in the late fall, when the harvest work was finished. That is to say, a little less than half remained as permanent settlers in Manchuria. But a marked increase occurring in 1926, and the still more extraordinary increase in 1927, constituted virtually a new phenomenon. Civil war between the South [nationalists based in Nanking] and the North [war lords, imperialists in Peking] was again raging in 1926. Especially in Shantung [Shandong], Chihli [Hobei] and Honan provinces, warfare, the prevalence of banditry, tax extortion, etc. drove out the native population, who were desperately seeking refuge and the benefits of peace and order which Manchuria only offers. In the late fall of 1926, contrary to the tendency during the same season of any previous year, many hundreds of thousands of Chinese immigrants arrived and continued to enter in increasing numbers throughout 1927 during which, it was estimated, no less than 1,178,254 persons arrived. Of these, 5999.542 landed at Dairen, 182,558 at Yingkou, 68,558 at Antung, and 327,645 were carried by the Peking-Mukden [Beijing-Shenyang] Line. The refugee immigrants bringing with them their families and chattels, came with the determination to settle permanently in Manchuria. The statistics taken at Dairen show that the number of those returning to their home provinces greatly decreased, as follows: [table of statistics omitted] |

The Second Report on Progress in Manchuria to 1930 (The South Manchuria Railway, Dairen, April, 1931) goes on to say this (page 21).

|

When the war was moving in the direction of Peking and Tientsin [in 1928], and the situation became so menacing as to threaten the Japanese interest in Manchuria, the Japanese Government sent both belligerents a Memorandum of warning, which intimated that Japan would take appropriate steps to keep the belligerent armies out of Manchuria. . . . As before stated, what Japan wishes, as far as possible, is that Manchuria be not involved in civil war or other disturbances. It is a matter of simple fact that Manchuria, especially South Manchuria, is a region in China where civilized people can live and trade with more guarantee of safety. Russia in former times undoubtedly deserved credit for maintaining peace and order in North Manchuria, especially in the zone of the Chinese Eastern Railway. But, after the Bolshevik revolution . . . . |

The Sixth Report on Progress in Manchuria to 1939 (The South Manchuria Railway Company, Dairen, May, 1939) -- the last volume in this series -- concludes with these paragraphs (pages 136-138).

|

44. Chinese Coolie Immigration Into Manchuria The Chinese mass immigration into Manchuria passed the million mark during 1927, 1928, and 1929. In 1927 was reached the peak, no less than 1,159,000 entering and only 316,000 leaving, thus chalking up a net gain of 843,000. Since 1930, however, it gradually declined and reached, largely a new low mark of 414,000 in 1932. During 1932, moreover, 498,000 left Manchuria, thus spelling a net loss of some 84,000. With the establishment of Manchoukuo and the gradual restoration of peace and order, Manchuria once more began to attract Chinese immigrants and the wave of mass immigration started to rise again. The establishment of Manchoukuo had changed the whole outlook for the free Chinese immigration into Manchuria. The new State deemed it necessary, at least during its formative period, to effect a rigid control of labor and immigration, especially for political and economic reasons, and it began to develop a national policy of controlling free Chinese immigration into Manchuria. This policy of control became clearer with the passage in 1933 of the "Regulations Governing the Entrance of Foreigners." It was reenforced in 1934 by the creation of the Labor Control Commission and the establishment of the Tatung Kungssu [大東公司], the former to study the demand and supply of labor and to decide upon the necessary amount of labor, and the latter to exercise the actual control over the Chinese immigration into Manchuria through the adoption of a permit system. This policy of control became definite with the passage in 1935 of the "Regulations Governing Foreign Laborers." With these plannings, regulations, and organizations the effective control of Chinese mass immigration into Manchuria was finally established during 1935 (For detailed discussion of this development, see Fifth Report, Section 45). As a result of such a policy of control, the Chinese coolie immigration into Manchuria began to decrease since 1935. The following figures, according to the Tatung Kungssu, give a summary view of the situation at a glance. [ Omitted -- Four tables of migration data for 1936, 1937, and 1938 by arrival and departure, industry of employment, province of origin in China, and province of destination in Manchuria ] In reviewing the above figures, one should remember two fundamental factors affecting the labour situation in Manchuria today. The one is the general construction activities which have been proceeding in Manchuria since the establishment of Manchoukuo, greatly preenforced by the new Five-Year Industrial Plan, which annually requires an increasing number of coolies. The other is the current China [Marco Polo Bridge] Incident which broke out in July, 1937, and which affected the sources of coolie supply in China. As a result, the country [i.e., Manchoukuo] has been witnessing a shortage of labor supplies during 1937 and 1938. It is for this reason that the Labor Control Commission at Hsinking decided on December 5, 1938, to make a positive effort in inviting 1,000,000 Chinese coolies from North China during 1939. this number was later reduced to 910,000. The Tatung Kungssu has already started a campaign to realize such a large-scale importation of Chinese coolies into Manchuria for the first time since the establishment of the new State. |

1939 Special Kenpeitai

The Special Kenpeitai was set up in Manchoukuo as the Kwantung Army was being routed by Soviet forces in what Japanese historians call the Nomanhan Incident. The incident was an undeclared war between Japan and the Soviet Union over the border between Manchoukuo and Mongolia.

The Special Kenpeitai, or "Special Legal Military Corps" (特設憲兵隊 Tokusetsu Kenpeitai), was created on 1 August 1939, by the Kwantung Army, to augment the military police (憲兵 Kenpei) units (隊 tai) already deployed throughout greater Manchuria, as a countermeasure to what the military regarded as an increase in anti-Japanese espionage in the regions under Japanese control, as well as in bordering regions of Mongolia, China, and the Soviet Union.

The special corps was headquartered at Kwanchengtzu (寛城子 WG Kuanchentzu, YP Kuan1chéengzĭ) in Hsinking (新京 WG Hsingching, PY Xīnjīng), the capital of Manchoukuo, known both before and after the rise and fall of the state as Changchun (長春 WG Ch'angch'un, PY Ch´ngchūn).

Before examining the particulars, though, an overview of the Nomanhan Incident and its political fallout would be helpful. The incident took place on the watch of Hiranuma Kiichiro, who helped introduce fingerprinting to Japan when an official of the Ministry of Justice.

Hiranuma Kiichiro and Nomanhan

Hiranuma Kiichiro served as prime minister from 5 January 1939 to 30 August 1939. As a nationalist, he was more interested in focusing on the consolidation of Japan's military and political position in China. He was therefore against forming of an alliance with Germany and Italy, which were beating the war drums in Europe, as such an alliance would risk confrontation with the United Kingdom and the United States in the event aligned themselves against Germany.

Things didn't go quite as Hiranuma had hoped, either in on the war front with the USSR or on the diplomatic front in Europe. By the end of August, he and his cabinet had resigned over foreign policy failures related to the signing of the German-Soviet Nonaggression Pact in Moscow on 23 August and the defeat of the Japanese Army in the Battle of Khalkhyn Gol, which had been raging since May.

The battle takes its name from the river that ran through the battlefield. Japan regarded the river as the border between Manchoukuo, which it controlled, and Mongolia, supported by the Soviet Union. Mongolia and the Soviets located the border several kilometers to the east of the river, near the village of Nomonhan. Japanese historians call the war the Nomonhan Incident -- one of several border disputes between Japan and the USSR at the time, by far the largest and most disastrous for Japan.

Hiranuma's cabinet resigned the day before the battle ended, and Hitler attacked Poland the day after, thus beginning World War II in Europe.

Japan signed the Tripartite Pact with Germany and Italy on 27 September 1940. On 13 April 1941, Japan and the Soviet Union signed a neutrality pact. On 21 June, Germany invaded the Soviet Union.

Japan attacked Pearl Harbor and commenced its campaign in Southeast Asia on 7 December 1941, banking on the USSR, busy with Germany on its western front, to honor the neutrality pact. It did -- until the war in Europe ended in May 1945. On 8 August 1945, the Soviets, as promised in the secret Yalta Agreement of February, invaded Manchuria, and a week later Japan surrendered.

| Special Kenpeitai with fingerprint unit created in Hsinking, Manchoukuo in 1939 | |

Japanese textThe Japanese text is a somewhat reformated version of material selected from postings on a website of uncertain provenance (see Source). A couple of characters, which appear to have been misentered or corrupted in scanning, have been corrected. English translationThe translation is mine (William Wetherall). Highlighting and bold emphasis is also mine. SourceThe material is attributed to 日本憲兵正史:特設憲兵隊の創設 [The correct history of Japan's military police: The establishment of the Special Kenpeitai]. This source appears to be the first volume of the following two volumes published by the National Kenpeitai Friendship Association. 全国憲友会 Zenkoku Kenyūkai 日本憲兵正史 日本憲兵外史

1983年, 1400ページ (限定版) I have not yet been able to consult these volumes, to determine whether the posted materials are direct extracts or paraphrases, or to otherwise confirm their veracity. |

|

|

特設憲兵隊の創設 [ 省略 ] 昭和十四年八月一日、ノモンハン事件の最中、関東憲兵隊に特設憲兵隊が創設された。創立の趣旨は敵性諜報謀略に備え、無線探査と科学捜査、鑑識によって原因を糾明し、あるいは検挙した諜報謀略員を培養して敵の企図を諜報し、軍の作戦行動を容易にするなど、その任務は時局柄極めて重要であった。 [ 省略 ] 創立当時の編成は次のとおりである。 昭和十四年八月一日(新京・寛城子) 特設憲兵隊隊長 副官印 本部付 第一分隊長(無線探査) 第二分隊長(無線探査) 第三分隊長(指紋) 第四分隊長(法医・細菌) 第五分隊長(写真) 第六分隊長(科学) [ 省略 ] |

Establishment of Special Military Police Corps [ Omitted. ] On 1 August 1939, in the middle of the Nomanhan Incident, the Special Legal Military Corps [Military Police Corps] (特設憲兵隊 Tokusetsu Kenpeitai) was established in the Kwantung Legal Military Corps (関東憲兵隊 Kantō Kenpeitai). The purport of its creation was to provide for [defend against] enemy espionage (諜報謀略 intelligence and strategy ), scruitinze its causes by wireless exploration [radio survillance] and scientific investigation and identification, or to cultivate arrested agents (諜報謀略員 espionage personnel) and [gather] intelligence on enemy plots, and facilitate strategic movements of the military, et cetera, and that mission, in the current situation, was extremely important. [ Omitted. ] The composition [of the special corps] at the time it was founded is as follows. 1 August 1939 (Hsinking, Kwanchengtzu) Corps Commander Adjutant Headquarters Commander 1st Section Commander (Wireless exploration) 2nd Section Commander (Wireless exploration) 3rd Section Commander (Fingerprinting) 4th Section Commander (Forensic medicine and germs) 5th Section Commander (Photography) 6th Section Commander (Science) [ Omitted. ] |

|

第三分隊(指紋担当) 万人不同と終生不変が指紋の特性である。わが国の指紋法は、明冶四十年、司法省では現行刑法に定められた再犯加重を行う場合、再犯者なることを何によって証拠立てるのか、という点が問題になった。ところが、当時、ドイツの警察制度を視察研究して帰朝した平沼麒一郎(後の首相)の提案によって、昭和七年八月十七日、司法省訓令で分類性を統一したが、これが日本において実施された統一指紋法である。すなわち、犯罪捜査および刑事裁判など、警察的に用いられる基礎が確立した。そして憲兵司令部がこれに着目した。 一方、満州においては、満州事変後、すでに南満州鉄道株式会社が、労働者(主として満人苦力)の不正移動や賃金支払に当たり、誤払防止を目的に、日本における指紋法をそのまま取入れて実施したのが、最初のことであった。 その後、満州国が独立、首都新京に指紋管理局が創設されたが、日本より多数の技術者を迎え、日本の指紋法に若干の修正を加えて実施したのが、満州国指紋法であった。 第三分隊(分隊長四宮祐二少尉)の任務は指紋の実用的処理および現場指杖の検出、採取の教育訓練であった。後にソ満国境全線および満州国主要都市において、住民および軍人、軍属の十指指紋を採取収集管理して、謀略防衛または各種犯罪の犯人割出しに利用されたことは、意外に知られていない。 |

3rd Section (In charge of fingerprinting) "None-the-same-in-10,000-people" and "unchanging-through-life" are the characteristics of fingerprints. In 1907, in the Ministry of Justice, the point became an issue, as to how in the event of carrying out an increased punishment for a repeated offense as determined in the operating penal code, by what could it be proven that [a culprit] was a repeat offender. However, at the time, because of a proposal by Hiranuma Kiichiro (later a prime minister), who had [just] returned having visited Germany to study its police system, on 17 August 1932, [the Justice Ministry] by a Justice Ministry instruction unified classifications, and this is the uniform fingerprinting that was implemented in Japan. In other words, a foundation from which [fingerprinting] could be used policingly, [in] crime investigation and [in] penal matter courts, became established. And the Kenpei [military police] headquarters fixed its eyes on this. Meanwhile, in Manchuria, after the Manchurian (Mukden) Incident of 1931, the South Manchuria Railway Company implemented fingerprinting methods used in Japan in order to prevent malfeancse in illegal movements and wage payments of laborers. After this, Manchoukuo became independent, and a fingerprint bureau was established in the capital of Hsinking, [it] welcomed a number of fingerprint technicians from Japan, and implemented [fingerprinting] addiding some modifications to the fingerprint method of Japan, but it was a Manchoukuo fingerprint method. The mission of the 3rd Section (Section Commander Second Lieutenant Shinomiya Yuji) was [both] practical processing of fingerprints and education and training in the detection and extraction of on-site [such as crime scene] fingerprints. That later, [along] the entire border of the Soviet Union and Manchuria and in the major cities of Manchoukuo, [the division] extracted, collected, and managed [controlled] ten-finger fingerprints of residents, military personnel and military affiliated [persons, and that [the fingerprints] were used in defense against conspiracy in indexing criminals by type of crime, is not [as well] known as expected. |

Shinomiya YujiShinomiya is first identified as a warrant officer (准尉), then as a second lieutenant (少尉), which was one rank higher. Either there is a mistake in the text, or he was promoted. |

|

Puppet Palace Museum

Pu Yi's home now a museum

Tanaka's article features a low resolution image of an identification certificate of a Chinese man showing his photograph and a fingerprint. The caption attributes the certificate to the 偽皇宮陳列館 or "Sham [puppet] emperor's palace exhibition hall" (伪皇宫陈列馆 Weihuanggong Chenlieguan "Exhibition Hall of Imperial Palace of Puppet Manchurian State") in Changchun.

The capital city of Jilin province is awash with historial museums, many of them about the Japanese occupation of Manchuria. This one is now called 伪满皇宫博物院 (Weimanhuanggong Bowuyuan) or "Museum of Imperial Palace of Manchu State" [偽滿皇宮博物院 Sham Manchu emperor's palace museum] -- the palatial residence of Pu Yi, the Last Emperor, part of the Jilin Provincial Museum.

Sources

Tanaka 1987

田中宏 Tanaka Hiroshi

指紋押捺の原点:中国東北部(旧満州)を歩いて

Shimon ōnatsu no genten: Chūgoku Tōhokubu (Kyū Manshū) o aruite

[The starting point of fingerprint: Walking Northeast China (Former Manchuria)]

朝日ジャーナル Asahi jaanaru [Asahi journal]

一九八七年一0月九日号

9 October 1987, pages 21-23

Takara 1988

高良鉄美 Takara Tetsumi

外国人登録法の指紋押捺規定の合憲性

Gaikokujin tōroku hō no shimon ōnatsu kitei no gōkensei

[The constitutionality of the fingerprint impression provisions of the Alien Registration law]

琉大法学、第42号、1988

Ryūudai hōgaku (University of the Ryukyus Repository), No. 42, 1988

Pages 43-55

Wang 2000

王紅艶 Wang Hong Yan

「満洲国」の労工に関する史的研究:華北からの入満労工を中心に

"Manshūkoku" no rōkō ni kan suru shiteki kenkyū: Kahoku kara no nyū-Man rōkō o chūshin ni

[Historical research concerning coolies in "Manchoukuo": Centering on coolies entering Manchuria from Northern China]

Doctoral disseration, Hitotsubashi University, May 2000

Graduate School of Social Sciences, Faculty of Social Sciences

"Northern China" refers to the present-day provinces of Honan, Hobei (Hopei), Shandung (Shantung), Shanxi (Shanhsi), Shaanxi (Shanhsi), and the municipalities of Beijing (Peking) and Tianjin (Tientsin) districts.

Wang graduated in Japanese from Hubei University in 1988 and studied Japanese at Aichi University until 1993. He received an MA and a PhD in sociology from Hitotsubashi University in 1996 and 2000. His main research themes have been labor problems in Manchoukuo and the history of Sino-Japan relations.

Wang is a protege of Tanaka Hiroshi (b1937), the first listed of the four members on his dissertation examination committee. Tanaka, who graduated from Hitotsubashi Univeristy in 1963 and later became a professor at Aichi University, returned to his alma mater in 1993, and Wang also transferred there. Tanaka became emeritus at Hitotsubashi in 2000.

|

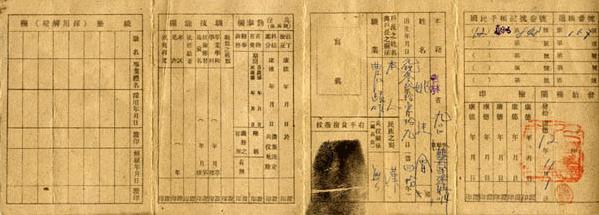

Manchoukuo national handbooks during World War II Controlling labor migration with photographs and fingerprints |

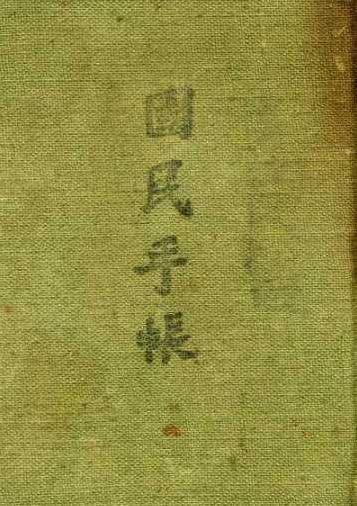

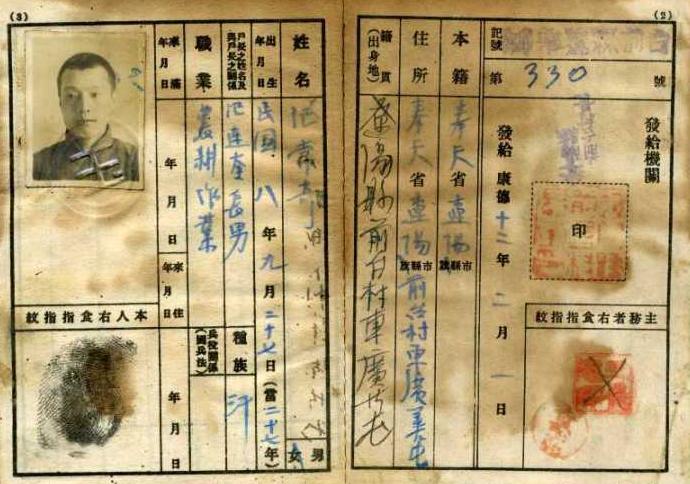

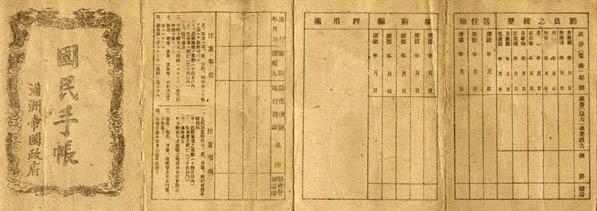

Manchoukuo national handbooksThe Government of the Empire of Manchoukuo issued handbooks and identification certificates to nationals called 國民手帳 (Kokumin techō). The certificate was a strip of paper printed on two sides and folded twice. There was a box for a photograph and a box for a finterprint. There was also a box for noting the bearer's racioethnic status. Such documents were written in Chinese, but some content -- such as instructions in the use of the documents and content related to moral education -- was also written in Japanese. The two versions of such documents that I have seen show some variation in terminology. |

|

29-page bound Manchoukuo national handbook issued to Mongolian cultivator |

|||||||||

|

The following images were copped and cropped from a larger set of images posted by Kato Masahiro (加藤正宏). The transcriptions and explanatory information are mine. The images are part of an article titled 満州国で日本語教育を受けて [Receiving a Japanese language education in Manchoukuo]. The article is one of a series Kato has been writing on the history of Changchun (長春 Ch´ngchūn). Kato went from teaching world history at a high school in Hyogo prefecture to teaching Japanese at universities in China. So far he has taught three two-year stints, first in Xian, then in Changchun, and most recently in Shenyang. His website -- 加藤正宏の中国史跡通信 [Kato Masahiro's reports on Chinese historical sites] -- contains a number of very interesting features on the history of particularly Northeast China, the heart of Manchuria. |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

NumbersNote that all the numbers are written in characters. AgeThe man's year of birth is the number of years from the first year of the Republic of China in 1912. Hence "Minkuo (Mínguó) 8" is 1919. Since the first year of Kangte (Kāngdé) was Minkuo 23 or 1934, the man's age in years -- including the year in which he was born, and the present year -- is 27. |

|||||||||

|

8-page foldout Manchoukuo national handbook issued to Han farmer |

||||||||

|

The following images were copped and cropped from the collection of military memorabilia on 鎮魂の旧大日本帝國陸海軍 -- which also calls itself "Requiem / Imperial Japanese Army & Navy". The transcriptions and explanatory information are mine. The "鎮魂 (requiem)" link is quiet photographic essay on events between the Manchurian Incident and the Tokyo Tribunals -- quiet once "Kimigayo" stops playing. The name of the website translates "Former Imperial Japanese Army and Navy of calm souls" and literally means the military forces of the Japanese Empire that continue to exist as calm souls. The site was established in the year 2664 of the Imperial Era, and message to visitors is dated the 6th month of 2667. I visted the site on the 8th day of the 12th month of 2667. The website features what may well be the largest single collection of images in the known universe of anything and everything related to the rise and fall of the Japanese Imperial Army and Navy -- though its webmaster and sponsors may not care to describe it this way. By all means visit the site -- but mute your speakers, because the sound tracks that accompany every feature are truly annoying. |

||||||||

|

||||||||

NumbersNote that some of the numbers are written as arabic figures. This suggests a lower level of formality on the part of the official who entered the numbers. |

||||||||

National labor handbook laws

The issuance of national identification documents in Manchoukuo was inspired by spread in use of national labor handbooks in the prefectures and other territories that were part of Japan or under Japanese control.

Shen Tiantian (沈恬恬), in the Division of Studies on Cultural Forms and Japanology at the Graduate School of Letters of Osaka University a graduate student at Osaka University (大阪大学文学研究科文化形態論日本学専攻), describes some developments in labor handbook laws as follows (source details below, translation mine).

|

The "National Labor Handbook Law" (国民労務手帳法) was applied to the South Pacific Islands from 1 May 1924. (12) Also, on the basis of a Karafuto implementation order for the National Labor Handbook Law, national labor handbooks were adapted to Karafuto from 20 July 1942. (13) Furthermore, on 21 December 1943, the "National Handbook Law" (国民手帳法) in which the "National Labor Handbook" (国民労務手帳) was versioned up was promulgated in "Manchoukuo" (満州国), and was executed from 1 January 1944. |

Source沈恬恬 Shen Tiantian |

Manchoukuo national precepts

The postologist Naito Yosuke (内藤陽介) has blogged some stamps and other information related to Manchoukuo during the Pacific War (viewed 8 December 2007). One stamp is particularly interesting, as it relates to the introduction of moral precepts that made their way into Manchoukuo's national handbooks. Though Naito does not talk about the handbooks, he accurately summarizes the precepts.

On 8 December 1942, the government of the Empire of Manchoukuo issued a printing of its standard 3-fen stamp overprinted with the slogan "興亜自斯日 / 8. / 12.8" meaning "Enhance Asia from this day / 8th year / 12th month 8th day" -- meaning 8 December 1941. Japan launched its war to rescue Asia from European from all colonial powers but itself on the 8th of December in the 8th year of the reign of Pu Yi, who on 1 March 1934 became the emperor of the country founded on 1 March 1932.

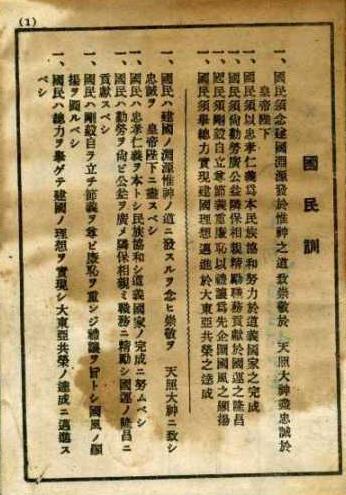

Also on this first anniversary of the war, the government of Manchoukuo established "National precepts" with National Assembly of Manchoukuo Proclamation No. 17 (Naito). There were five precepts, covering everything from Ameterasu, loyalty, modesty to achieving the aims of the Great East Asia Co-Posterity -- in Chinese followed by Japanese.

National precepts in National Handbook

Manchoukuo's national precepts, as featured in the National Handbook in Chinese and Japanese, were as follows (my transcriptions and translation).

To be continued.

|

National precepts in Manchoukuo National Handbook |

||

| Chinese | Japanese | English |

|

|

|

|

Shenyang's 9.18 History Museum

The national handbooks issued in Manchoukuo have gotten quite a bit of publicity in China. The aquisition of such a handbook by the 9.18 History Museum in April 2002 was widely reported as news throughout the country.

A number of websites carried a version of the following brief (translation mine).

4月20日,一件日偽時期“國民手帳”被遼寧省瀋陽市“九一八”歷史博物館收藏。“國民手帳”是日偽統治時期日本侵略者發給中國百姓的,相當於現在的身份證明。這種手帳是1945年2月下發的,內有當時瀋陽市敷島區區長高垣四郎的名字和印章。

On 20 April [2002], a Japan-period "National handbook" was collected by the "918" History Museum of Shenyang city in Liaoning province. A "National Handbook" was equivalent to a present-day identification certificate which, during the Japan-rule period, Japan invaders issued to China commoners [one-hundred surnames]. This kind of handbook was issued from February 1945, and contains the name and seal of Takagaki Shiro, district head of then Fudao district, Shenyang city.

Xinhua Net report

A longer article by Shí Qìngwĕi (石慶偉), a Xinhua News Agency reporter in Shenyang, was featured on Xinhua Net (新華網) and carried by other on-line news services.

Shí's article reports that the handbook was contributed to the museum by a 75-year-old Shenyang man who had had it in his personal collection.

The article noted that the handbook was made of paper, was 14 cm long, 7.5 cm wide, and 0.3 cm thick, was bound in a grass-green canvas cover, and on the font there were the three characters of "Fengtien province" in red and also the four black characters of "National Handbook", and it had 29 pages.

It notes that the handbook included the five-article "National Precepts" in Chinese and Japanese, and had entries ranging from the name of the issuing organ, to particulars about the bearer, and fingerprints.

Fudao district (敷島區 Fūdăoqū) is identified as the presentday Beishichang area (北市場地區 Bĕishìchāng dìqū) of Shenyang city.

The brief cited above appears to be a paraphrase of a paragraph in Shi's article, which attributes the explanation of the handbook to an annonymous expert.

"9.18" History Museum

The "9.18" History Museum ("九・一八" 歷史博物館 ) displays memorabilia related to what is most widely known as the Manchurian Incident (満州事変 Manshū jihen) or the Mukden (WG Fengtien, PY Fengtian) Incident (奉天事変 Hōten jihen). Its name reflects 18 September 1931, the day members of Japan's Imperial Kwantung Army are alleged to have dynamited an short stretch of ordinary track belonging to the South Manchuria Railway, near lake Liutiao in Fengtian, present-day Shenyang.

In China, the apparently staged sabotage is most commonly called the "9.18 incident" (九・一八事變 Jiŭyībā shìbiàn). It is also known as the Liutiao Ditch Incident (柳條溝事變 Liŭtiáogōu shìbiàn), though the track, only slightly damaged, did not bridge anything, and does not seem to have run along anything resembling a ditch, canal, or other waterway.

The museum is located in the Dadong district of Shenyang city (No. 46, Wanghuananjie, Dadongqu, Shenyangshi), in the vicinity of Liutiaohu (柳條湖). The original museum, which opened on 18 September 1991 to mark the 60th anniversary of the Manchurian Incident, stands in the middle of the plaza of the much larger museum, which opened on the same day in 1999.

The older museum is called "The Broken Calendar Monument" (残暦碑) in English -- a somewhat quaint reflection of an expression that literally means "remaining calendar monument" -- the vestiges of a calendar left behind, bequeathed, abandoned. The edifice, built of stone-blocks, represents a calendar frozen open at 1931.9.18, when it was riddled with bullets and blasted by bombs. Though now closed, it remains a dramatic favorite of photographers.

The huge billboard has a guide map and overviews in Chinese, English, and Japanese. I have not been able to access the museum's website.

"九一八" 历史博物馆 (The "9.18" Historical Museum)

"Never forget '918'" (勿忘 "九・一八") reads a slogan on a memorial in the plaza and at the exit of The "9.18" History Museum in Shenyang. On 18 September, a large memorial bell is struck fourteen times, once for each of the years that Manchoukuo existed, from 1932 to 1945. The tolling of the museum's bell is joined by the ringing of other bells, the sounding of sirens, and the blasting of horns throughout Shenyang city and Liaoning province.

Dominating one side of the museum's bell -- making it one of the most popular props for hands-on I-was-there photographs -- is calligraphy reading "Never forget national humiliation" (勿忘國耻).

National Defense Education Day

In the Spring of 2001, in preparation for observing the 100th anniversary of the 1901 Boxer Protocol or the 1931 Manchurian Incident, there were movements in the Chinese government to establish a "National Humiliation Day" (国耻日 guóchĭrì).

One candidate was 7 September 1901, when the Qing Dynasty was forced to sign the Boxer Protocol. The treaty gave the United States, Great Britain, France, Russia, Germany, Japan, Italy, and Austria-Hungary -- as well as Belgium, Spain, and The Netherlands -- unprecedented extraterritorial rights in China, as settlements of incidents which provoked the invasion and occupation of Peking by allied armies of the first eight of these countries to suppress the so-called Boxer rebellion or uprising in 1900.

Another candidate was 18 September 1931, which is taken as the start of the "Fifteen-year [Sino-Japanese] War" (1931-1945).

Another candidate which would have implicated Japan was 7 July 1937, when the Kwantung Army issued an ultimatum to China to permit its troops to cross the Marco Polo Bridge in Peking on the pretext of looking for a missing Imperial Army soldier. Japan commenced its invasion and occupation of Peking and the rest of northern China the following day. By the end of the year, Japan had invaded and occupied Shanghai, Nanking, and numerous other Chinese cities. The "7.7 Incident" or "Marco Polo Bridge Incident" is taken as the start of the "Second Sino-Japanese War" (1937-1945).

The first candidate appears to have been the stronger because it encompasses more history -- and, unlike the other two, it does not single out Japan as the only Japan that humiliated China. But the idea of an official National Humiliation Day was tabled as too controversial, both domestically and internationally.

Instead, at its 23rd meeting on 31 August 2001, the Standing Committee of the Ninth National People's Congress enacted a law on national defense education, which sets the third Saturday of September as "National Defense Education Day of the Whole People" (全民国防教育日).

The proximity of the third Saturday of September to the Manchurian Incident was a clever way to kill several birds with one diplomatic stone. There are numerous historical museums and sites in China dedicated to remembering the misfortunes of the Fifteen Year War and which country was most responsible. All resonate with the bell that rings on 18 September.