Catch 51: A Han-Japa Odyssey

By Kunioki Yanagishita

Translated by Kunioki Yanagishita and William Wetherall

Posted 16 April 2021

Updated 23 May 2021

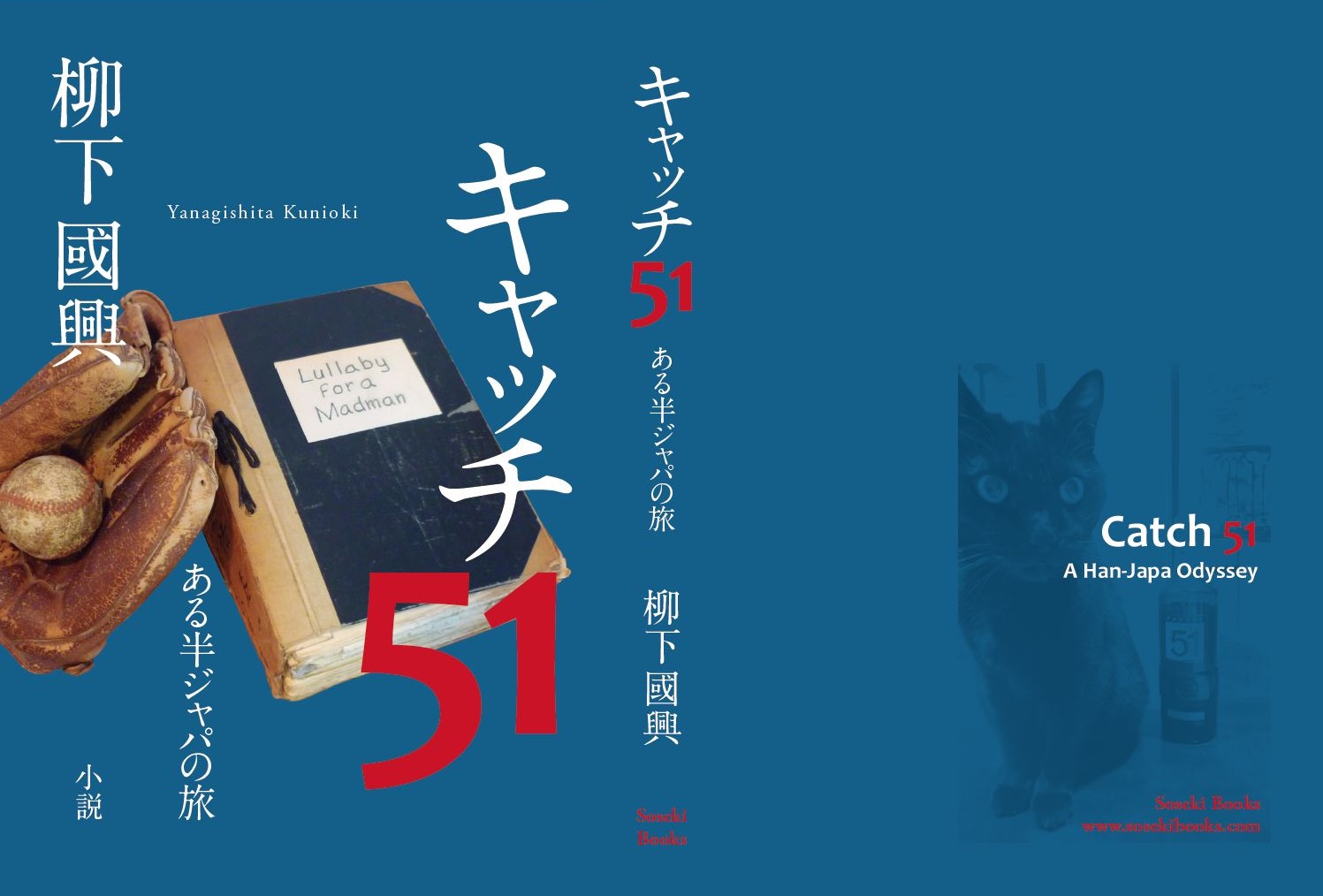

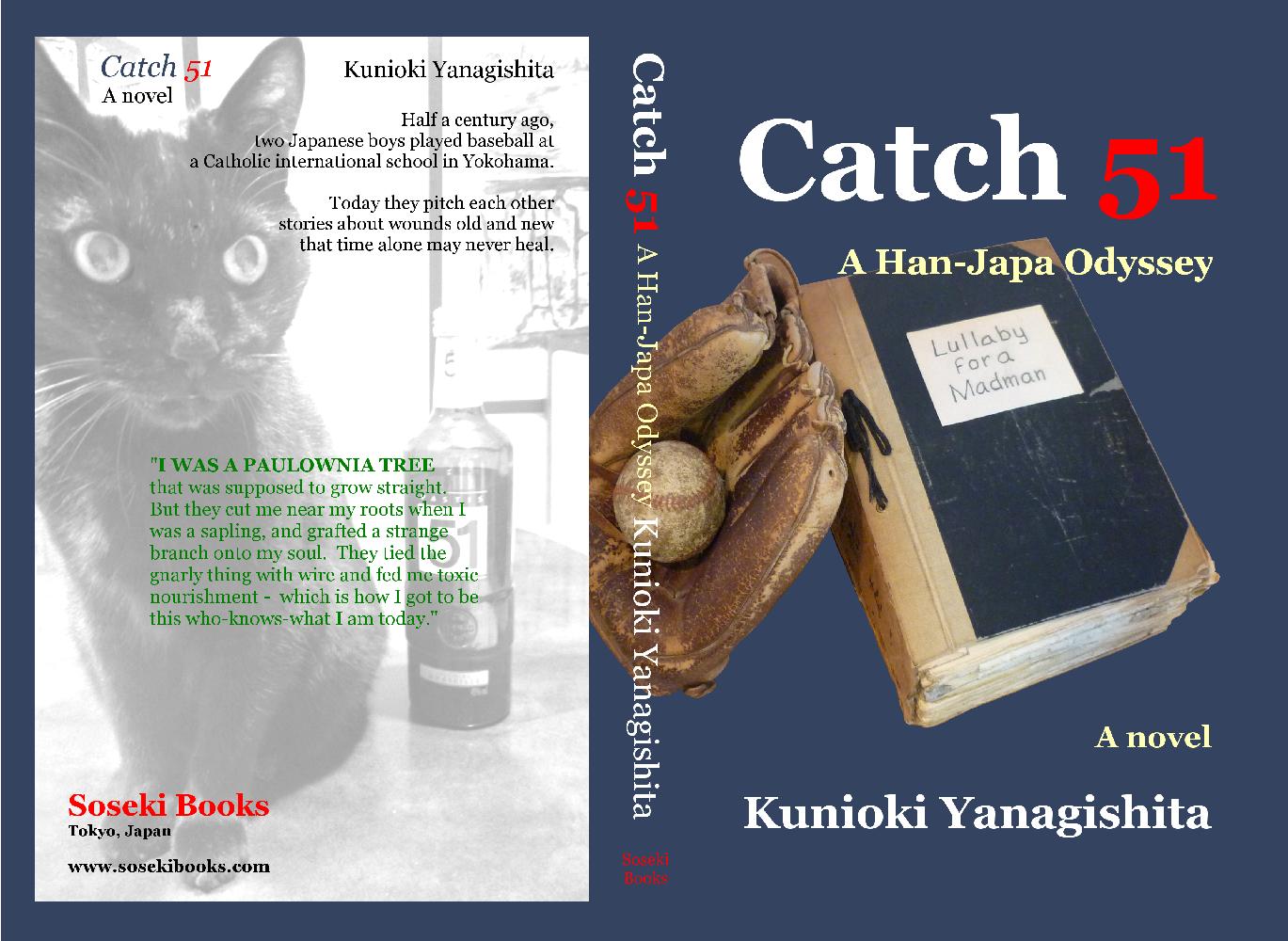

öº » Yanagishita Kunioki Kunioki Yanagishita The Japanese and English editions were published simultaneously. The novelCatch 51 is narrated by Kimiyoshi Sugawara, born and raised in Yokohama, whose parents, both Japanese, send him to St. James, a boys Catholic school run in English by foreign brothers of the cloth. Yoshi's favorite brother, who teaches literature and coaches the baseball team, turns out to be a pedophile -- and Yoshi nearly becomes one of his victims. In college, Yoshi -- unversed in Japanese literature and history on account of his parochial Americanized education -- is dubbed a "han-Japa" by a dorm mate who regards him as a half-baked Japanese. Decades later, the "half-Jap" label continues to haunt him as much as his memories of sexual abuse. One morning, while Kimiyoshi is reading a newspaper report of an on-going sexual abuse scandal at a Christian school in Tokyo, the phone rings. He picks up the receiver and is called by a name he hasn't heard or wanted to hear since high school. The caller is Robert Takeshi Toriumi, a St. James school friend he hadn't seen for 51 years. Kimiyoshi, who had turned his back on his youth and severed ties with school friends, agrees to meet Bob for lunch. And the two men, who had played catch when boys, begin to pitch each other stories about wounds old and new that time alone may never heal. The storiesÚ Stories Joe Joe ¶lÌqçS Lullaby for a Madman ¹WF[Y Saint James jbt KCU s°Ç Insomnia Äï Reunion ¼Wp Han-Japa «¹ Footsteps ÒÐî Author and Translators Author and translatorsKunioki Yanagishita (author and translator) was born in Yokohama in 1944 and graduated from International Christian University. He is a translator, and a bunraku and kabuki script translator and English commentator. His many English translations include Kenzaburo Oe's novel A Quiet Life (Grove, Japanese title Shizuka-na shiatsu) and overseas lecture Who's Afraid of the Tasmanian Wolf? (Rainmaker, Japanese title Tasumania urufu wa kowaku nai?). His Japanese translations include Dick Gregory's nigger (Gendai Shokan). William Wetherall (co-translator) was born in San Francisco in 1941 and graduated from the University of California at Berkeley, specializing in Japanese literature, society, and history. A researcher, writer, and novelist, his literary translations include Oe Kenzaburo, Oda Makoto, Takagi Nobuko, Matsumoto Seicho, Nishino Tatsukichi, Yanagishita Kunioki, and others. He has lived in Japan since 1975 and has Japanese nationality. |

Writing and translationA personal journey through two languagesKunioki Yanagishita was born in Yokohama in 1944 to a Hawaii-born mother and a Japan-born father. The stories of Catch 51, while fictional, are partly based on his own experiences at St. Joseph College or "St. Joe" in Yokohama through high school, and International Christian University (ICU) in Mitaka for college, in the 1950s and 1960s. He personally grappled with the stigmas that came from feeling "half baked" as a Japanese formally educated more in English than in Japanese -- though in time, through a lot of self-study and an interest in language and literature, he would become both fluent and savvy in both of his native parental tongues. From 1st draft to 1st editionYanagishita began writing the novel in the 1980s, and I first read it in the early 1990s in a binder-bound manuscript printed from a word processor. Ōe Kenzaburō introduced the first draft to Kōdansha, but the publisher turned it down, probably because of its bulk and narrative rawness -- a "rant" in Yanagishita's words. Many years later, Yanagishita significantly cut and partly revamped the story, but a different publisher turned it down, again for uncertain reasons. Then in 2016 he published it in an Amazon Kindle edition as 51 de kyatchibooru (TPÅLb`{[) under the name Yanai Kei (öä\). When I heard about the Kindle version, I bought a reader and read it mostly on trains and in waiting rooms. It was definitely a lot better -- more manageable in length and tighter as a story. The narrative compelled reading, but as a novel I thought it had some rough edges. Translation and revisionYanagishita then informed me that he had translated the Kindle edition and wanted me to join the project as a co-translator, much as I had when we worked together on what began as his English translation of Ōe Kenzaburo's 1990 novel Shizuka-na seikatsu as A Quiet Life, which Grove published in 1996. Working with Yanagishita's draft translation, while consulting the Kindle version, I did a lot of editing and some rewriting. A lot of fat was cut, some descriptions were dramatized, some characters were fleshed out, and some new scenes were added. Yanagishita reworked the Japanese version in line with the English revisions, and made more cuts and additions, which were worked back into the English version. An attempt was made to start the novel with the reunion and reveal the schoolday experiences later. But Yanagishita preferred the original order with some original scenes moved to unfold in real time. I suggested the prologue to set the stage. By this point I had provided the title and sub-title, and the story titles. Structural translation in actionIn the editing and rewriting process, the Japanese controlled the English when the narrative originated in Japanese. But at times the Japanese originated from a narrative created in English, in which case the English controlled the Japanese. The object of this give-and-take was a single coherent narrative in two languages. I adopted the view that the editing and rewriting were about narrative, not language. First and foremost, a writer needs to know what to show and not show, what to tell and not tell, and how the show and tell were to be conveyed in the course of developing characters and plots, and pacing larger and smaller stories -- all in the service of inducing readers to turn the pages. This may be taken as a definition of my approach to translation, namely, that narratives -- the structural elements of a story, including its logic and style -- and not languages -- are the proper objects of translation. In other words, the aim of translation is loyalty to the gods of narratives, not to the Caesars of languages. Trust the Japanese as written, trust the capacity of English to convey the same narrative with comparable efficacy -- and trust the reader's ability to figure things out without commentary. Kawabata and MurakamiProfessional Japanese-English translators commonly embrace various degrees of free translation because it's easier to retell the story as one thinks it might be told in English, than to closely emulate the narrative elements of the Japanese story. The best-known English translations of Japanese fiction are full of English wording and phrasing that depart from the Japanese narrative and style. Edward Seidensticker's English version of Kawabata Yasunari's Yukiguni as Snow Country is generally very smooth and inviting -- at times even beautiful. And there is no doubt that Seidensticker captured the larger flow and essence of Kawabata's narrative -- never mind his style. But if you read and grasp the narrative logic of Kawabata's Japanese, and understand why he chose to tell the story the way he did, then Seidensticker's version is not only different, but inferior -- less logical, less imaginative, less elegant -- where he has departed from the original. Reading only Snow Country, one experiences a wonderful story. Reading Yukiguni, aware of its narrative effects and how Kawabata crafted the narrative create them, one experiences a great story -- a wonderful story in higher resolution with more texture and depth. Narrative degradation is a problem in practically all commercial and not a few academic translations, in which the voice of the original is weakened by disregard for the an author's narrative choices. See The light at the end: Kawabata Yasunari's "Yukiguni" and Murakami Haruki's Lost Voice: Translating narrative style. Why co-translate?I was motivated to participate in Yanagishita's Catch 51 project as a celebration of our half-century of friendship, which began in 1970. And I was intrigued by the prospects of simultaneously publishing the novel in both languages, which walked the walk and talked the talk of the same narrative. This was not exactly Yanagishita's intention when he asked me to lend him a hand. He did not expect me to insist that he register a publishing company named Soseki Books and publish the novel under its imprint. And neither of us anticipated that we would spend two years whipping the Yanai Kei version of the original novel into a yet somewhat different version. I certainly did not set out to impose a theory of translation on my contributions. But as I wrangled with the differences I noted between Yanagishita's draft translation of the Kindle version and the Japanese, I recalled encountering similar problems when working with him on what became a co-translation of Shizuka-na seikatsu. Unlike when we co-translated Ō3's novel, which we had to accept as published, when working out the translation of Catch 51, we were free to improve the original -- which is what we did. The process of batting ideas back and forth, to improve both the original and the translation, sharpened my understanding of the possibilities and limitations of structural translation, which for me was an invaluable experience. Yanagishita and I have agreed over the years to disagree over many issues related to language and culture, among other aspects of the human condition. Catch 51 was a labor of contested writing, sometimes involving long and heated multiple email exchanges. In hindsight I belive it was worth it, and I feel very privileged to have had the change to learn and grow from his patience with my impatience. Cover artI thought both the title and the cover of the Yanai Kei Kindle version wrongly gave the impression that the novel was about baseball, which barely figures in the story. Yet when it came to retitling it, Catch 51, however seemingly meaningless, struck me as short and catchy. It also presented cover design possibilities. As for the cover, I suggested the composition of the photograph that Yanagishita's wife set up and took on a table in their home. The glove is one I bought in Sacramento during the summer of 1956, between the 9th and 10th grade, with a Grass Valley, California classmate, Phil Carveth (1941-1995 RIP). We had been playing baseball on school and summer teams -- he at 1st base and on the mound, I mostly at 3rd base, sometimes at 2nd or short, and a wannabe pitcher in a pinch. The binder contains authentic family stories that Yanagishita's grandfather wrote many decades ago. The label is one I printed on a discolored index card with a fat hand-sharpened carpenter's pencil. I cropped the glove and binder, against a transparent background, using Gimp. The photograph of the black cat beside the bottle of Pastis 51, taken in the Yanagishita home, was also doctored a bit with Gimp. The cat is a member of the Yanagishita family. The poster on the wall in the background is a lithograph of a painting by Bob Dylan. This much about the story is true. |