About the article

Web version

|

Authors

|

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Life in Japan

|

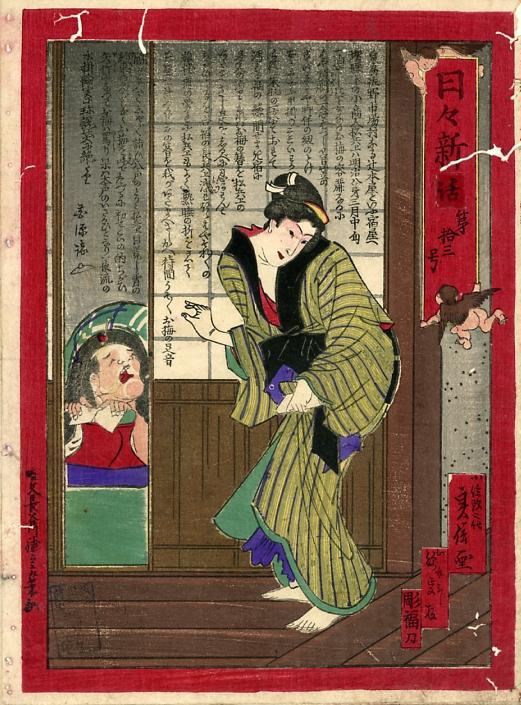

Nishikie with news

|

Rise and fall of news nishikie

|

Illustrated newspapers

|

TNS and YHS news nishikie

|

Newspaper and nishikie literacy

|

Translations and romanisation

Sidebars

Figure 2: Woodblock-printed newspapers

|

Figure 3: Shinbun suppression

Feature stories

Dog with woman's head (TNS 865a)

|

One majestic fold (TNS 726)

|

Raking fallen leaves (TNS 689)

|

Gifted wife (TNS 1015)

|

Three generations marry (YHS 650)

|

What the woman stole (YHS 527b)

Web version

"News nishikie: An arranged marriage that didn't last" was written by William Wetherall with some contributions from Mark Schreiber and vetting of translations by Akiko Sugimoto.

The article makes a number of original observations based on research first published on this website in 2004 and 2005.

The article features 18 color illustrations, 15 of which are of news nishikie. Six of the news nishikie are fully translated with commentary. Two illustrations show the practice of "shinbun suppression" on Osaka news nishikie.

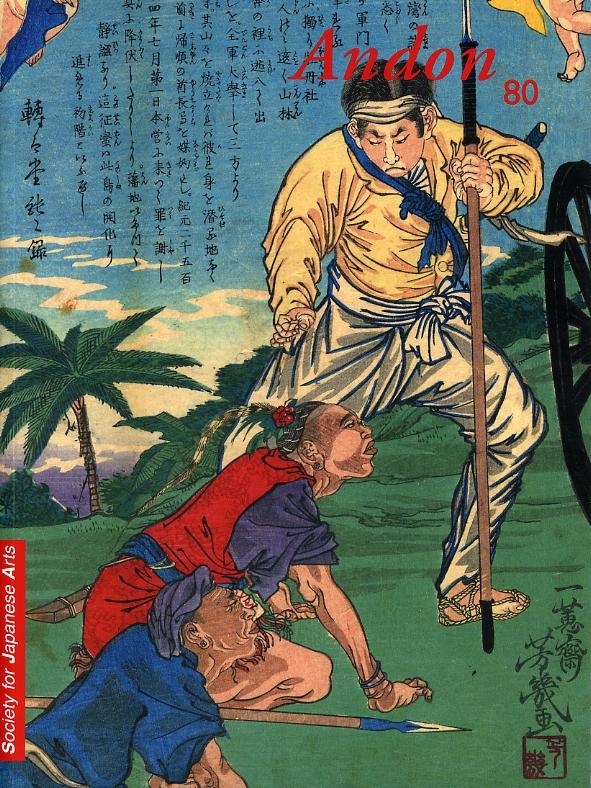

The version shown here restores some features of the original draft that were changed to accommodate Andon's style. The article was the cover story, and the editors laid it out essentially as I had designed it in manuscript -- including the captions. The editors, though, chose the cover image, from among those I submitted with the manuscript, without consulting me.

The issue also includes my review of a book with a chapter related to news nishikie: Written Texts - Visual Texts (Woodblock-printed Media in Early Modern Japan), edited by Susanne Formanek and Sepp Linhart (editors), Amsterdam: Hotei Publishing, 2005, Hotei Academic European Studies on Japan (ESJ) Volume 3. (WW)

Andon is edited and published by the Society for Japanese Arts in Leiden, The Netherlands.

The authors

The authors, both writers and researchers, have academic and journalistic interests in a number of subjects that reveal the human condition in Japan, where they reside. Their collaborations on a few news nishikie can be found elsewhere on this website.

Acknowledgements

Many of the interpretations in this article are based on original analyses of primary data compiled over the years by other researchers in Japan. As such, the authors stand on the shoulders of giants in the field, such as the late Ono Hideo (1885-1977), who pioneered journalism studies in Japan, and students of art and journalism history like Takahashi Katsuhiko and Tsuchiya Reiko. We list here only their single most recent and important work related to this article.

Ono Hideo, Shinbun nishikie [News nishikie], Tokyo: Mainichi Shinbun Sha, 1972.

Takahashi Katsuhiko, Shinbun nishikie no sekai [The world of news nishikie], Tokyo: Kadokawa Shoten, 1992 (first published in a slightly larger and somewhat different edition by PHP in 1989).

Tsuchiya Reiko (editor), Nihon nishikie shinbun shūsei [A collection of nishikie news in Japan] <A collection of illustrated ukiyoe newspapers [sic] as visual news media in early Meiji Japan>, Tokyo: Bunsei Shoin, 2000 (CD-ROM for Windows and Macintosh).

The authors also wish to thank Akiko Sugimoto for pointing out flaws in the early drafts of their translations. They take full responsibility for all oversights that may remain, and invite critical comments through their website, which is always being revised.

Unless otherwise credited, all images shown in the figures are scans made by the authors of original materials in private collections.

Introduction

Life in Japan

Imagine living in Japan in the early 1870s. It is larger, and more cultivated and civilised, than most countries in the world. From 1868, the victors of a civil war have set out to unite the country's dominions into an imperial state. Their aim is to build a nation that can cope with the impact that more intimate contact with other countries and their peoples is already having on your life.

You are one of about 40 million countrymen. You are not quite sure what to make of all the incidents and developments, about which you hear mostly (if at all) long after they occur, and then only in brief, by today's standards of intense reporting of important news. If you live in Osaka, you can read papers that arrive by sea from Tokyo a few days to a week later.

Otherwise your life is not much different from what it would be today. You cannot quite comprehend the enormity of the world or foresee how it will change. Mostly, you take each day as it comes and pray that life will get better. Your main concern is to survive as best you can within your own village or town, probably in much the same way as your parents and their parents before them.

You are probably a farmer. You can't read much, can write even less, and will die around the age of 40 never having journeyed to Tokyo or Osaka. You may well go to your grave, or be cremated, never having seen one of those new-fangled things called a newspaper. And you might never feel the texture of a colourful woodblock print (nishikie).

If, though, you are a member of the former warrior caste, a petty official or a merchant, an artist or writer, an actor or raconteur, you will be more literate. If you live in or near Tokyo or Osaka, or have opportunities to travel there, you will probably also have seen "news nishikie" at shops selling woodblock printed matter, if not among the publications being hawked by street vendors.

You might at times be tempted to buy a news nishikie or two for your own amusement or collection, or to give to friends or relatives you think might like the pictures and stories. But the odds are higher that, if you buy anything purporting to convey news, it will be a newspaper. And because they represent the new age, newspapers are becoming more popular than nishikie as souvenirs that you might take home to your friends and family.

Nishikie with news

"News nishikie" (nyuusu nishikie) is our name for "colour woodblock pictures with news-related stories". As many as 1,000 such prints are known. The majority were brought out between 1874 and 1876 by woodblock publishers who commissioned popular artists and writers to produce nishikie versions of human-interest stories instead of the usual historical tales. Most of the stories had also been reported in newspapers, but the writers recast them in more entertaining and didactic versions.

News nishikie were not newspapers. They were usually not newspaper supplements either, but independent publications with only tenuous, if any, connections with news companies. They appeared at a time when new methods of printing and disseminating pictures and stories, including illustrated news, were forcing woodblock publishers to innovate or perish. Wherever they were published, they were short-lived and sometimes controversial commercial ventures.

Most news nishikie did not, and could not, compete with newspapers as sources of news. They featured crime, suicide, accidents, rescues, male-female relations, and other stories of such general interest that it did not really matter if their versions came out weeks, months, even years later. Only a few news nishikie series were related to more recent events. Only one series, produced in Osaka, tried to become more like a newspaper, but it too ceased before it could achieve newspaper standards of promptness, credibility, variety, volume, and price.

While news nishikie may have been an early form of "visual news media", with emphasis on the word "news", illustrated newspapers reflected more the character of illustrated books. The founders of Tokyo's first daily newspaper later began the first news nishikie series and then the first illustrated paper. All were artists and writers who had worked together for many years, producing both nishikie, stories and illustrated novels, before they became newspaper pioneers. Even while building their newspapers, they continued to produce conventional nishikie and illustrated books.

The rise and fall of news nishikieMost early newspapers started as woodblock publications, and many woodblock artisans became newspaper people. In 1868, during the final weeks of the Tokugawa period, the book and nishikie writer Jōno Denpei (1832-1902), the nishikie publisher Hirooka Kōsuke (1829-1918), and the book dealer Nishida Densuke (1838-1910), helped Fukuchi Gen'ichirō (1841-1906), a samurai with political opinions, to publish Kōko shinbun (World news). They brought out 22 issues between late May and early July, when Fukuchi was arrested for his views. In 1872, while Fukuchi was abroad as a government official, Jōno, Nishida, Hirooka, and the nishikie artist and book illustrator Ochiai Yoshiiku (1833-1904), founded Tōkyō nichinichi shinbun (Tokyo daily news, from here refered to as Tonichi), Tokyo's first successful daily newspaper, now part of Mainichi Shinbun, which originated in Osaka. In 1874, Fukuchi joined his friends at Tōnichi as its editor and gained national fame when he personally covered the Seinan War in Kyushu in 1877. Becoming newspaper men did not keep Yoshiiku, Jōno, Hirooka, and others from engaging in their primary professions. In 1874, Gusokuya, a Tokyo nishikie publisher, enlisted Yoshiiku, and Jōno and other Tōnichi writers, to produce a series of nishikie versions of stories reported in past issues of Tōnichi. This first arranged marriage of news with nishikie bore the name Tōkyō nichinichi shinbun. But TNS, as we shall call this nishikie series, was not a Tōnichi supplement or otherwise directly related to the paper. Many other newspapers appeared in Tokyo after the Tōnichi, including Yūbin hōchi shinbun (Postal dispatch news, henceforth referred to as Hochi). In 1875, the nishikie publisher Kinshōdō engaged the artist Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839-1892), and a group of raconteurs and others who narrated and acted before live audiences, to produce nishikie versions of stories from past issues of Hōchi. This nishikie series, though not a Hōchi supplement, also bore the name Yūbin hōchi shinbun, so we are calling it YHS. Several news nishikie series also appeared in Osaka. The Osaka prints took many of their stories from Tokyo newspapers and even TNS and YHS, since Osaka did not yet have a successful newspaper. Some stories were local, however, and one, about two Kyoto lovers who disrobed before plunging into the Yodo river in Osaka, appeared in the 18 May 1875 edition of Hōchi, with a description of the Osaka nishikie that had featured it. However, the 29 May 1875 edition of Hōchi criticised both the YHS and TNS nishikie series, naming the artists Yoshitoshi and Yoshiiku, and a few Osaka series as well, claiming that their less than objective, if not untruthful, stories degraded the meaning of shinbun (news). By the end of June, the Osaka prefecture had forced nishikie publishers to remove "shinbun" from the titles of prints including this word. Most marriages of newspapers and nishikie were over by the end of 1875 -- a few months after the start and spread of illustrated newspapers in Tokyo, and shortly before the start of Osaka's first viable local papers. The only Osaka news nishikie series to begin after the 1875 crackdown on publishers ceased in September 1876. At the end of 1876, Gusokuya and Kinshōdō published a few more TNS and YHS prints, but these were unlike those of the discontinued main series. Most of these later prints featured local disturbances that triggered the Seinan War, which began in January 1877 and ended in September with the suicide of Saigō Takamori (1827-1877). The war inspired a spurt of news nishikie, both one-off prints and a few short series, some published during the war, some after, memorializing the victors and vanquished. |

Illustrated newspapers

News nishikie were conceived with the intention of making money, and they stopped when the promise of profit dwindled. The advent and spread of newspapers, increasingly illustrated, and the sheer fashionability of such newer media, hastened the extinction of this hybrid.

The same artisans who founded Tōnichi, and who brokered the marriage of news and nishikie, also pioneered illustrated newspapers. In the spring of 1875, Yoshiiku and the writer Takabatake Ransen (1838-1885), while producing TNS for Gusokuya, began publishing Japan's first illustrated paper, Hiragana eiri shinbun (Hiragana illustrated news, from here referred to as Eiri). They had stopped putting out TNS by that autumn, when Eiri began to be published daily, with Takabatake as editor and Yoshiiku as illustrator.

Eiri was set up as a subsidiary of Nippōsha, which published Tōnichi, and publicised its new sister not as a rival, but as a paper intended for people who wanted something written with more hiragana and fewer kanji expressions. As its name also implies, Eiri featured illustrations. It was also the first paper to serialise fiction: with pictures, of course.

What was the main inspiration for Eiri and other illustrated papers? Probably not news nishikie. There was already a long tradition of illustrating fiction and other stories with pictures. For many years, Yoshiiku and Yoshitoshi had been drawing illustrations for woodblock-printed books by popular writers, including Jōno Denpei. Even while doing TNS and YHS, they were illustrating books. Furthermore, the pictures they drew for papers were more like those they did for books -- full of the fine detail that carvers, and later engravers, loved.

Unlike other species of nishikie, news nishikie left no fertile offspring that we know of. Except in fashionable scholarship that leaps the decades -- and likens them to present-day tabloids, scandal-stirring weeklies, and gossipy magazines with stories built around paparazzi photos -- there are no genetic links between news nishikie and latter-day photo-journalism.

Photography, it is true, changed the way Meiji newspapers and magazines came to be illustrated. But even today, all major newspapers and magazines in Japan feature fiction, and even some non-fiction, illustrated by signed drawings -- in keeping with the traditions of their woodblock book roots.

Figure 2

Woodblock-printed newspapers

|

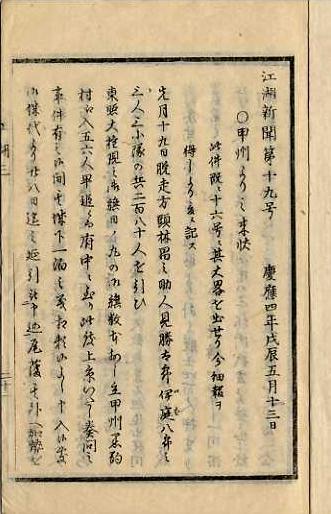

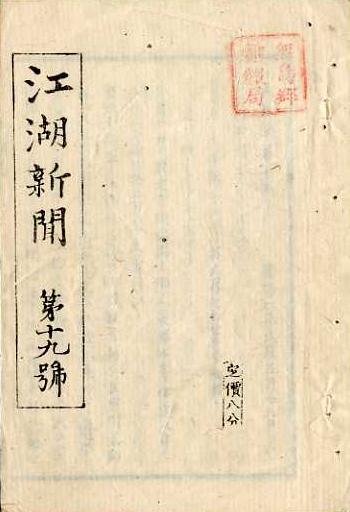

Figure 2: Two woodblock-printed newspapers showing differences in writing |

|

|

|

|

Figure 2a: Writing for the more literate Kōko shinbun (World news) No. 19, Keiō-4-Boshin-5-13 (1868-7-2), two days before the Shōgitai standoff at Ueno. Cover right, Page 1 left. Only two kanji have furigana to help read them. Kaeriten marks on the left side of the last column of text to the left facilitate reading a phrase written in Chinese syntax. |

|

|

|

|

Figure 2b: Writing for the less literate Yūbin hōchi shinbun (Yūbin postal dispatch) No. 27, Meiji-5-Jinshin-11 (1872-12), with illustration of postal steamer flag. Cover right, Page 9 (with flag) left. More kanji have furigana. Some kanji have furigana on both sides: Sino-Japanese pronunciations on the right, Japanese meanings on the left. Phrases in Chinese syntax have both kaeriten and furigana. |

|

Figure 3

Shinbun suppression

|

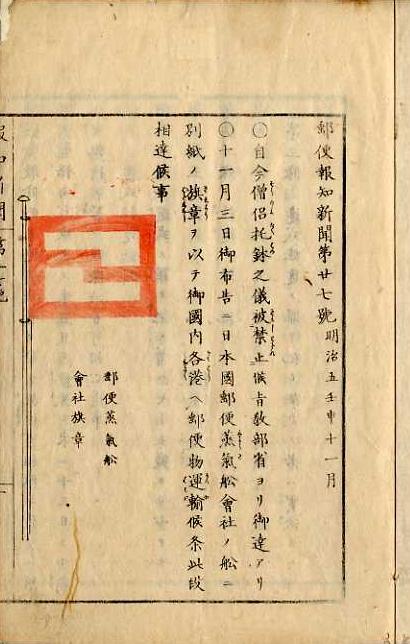

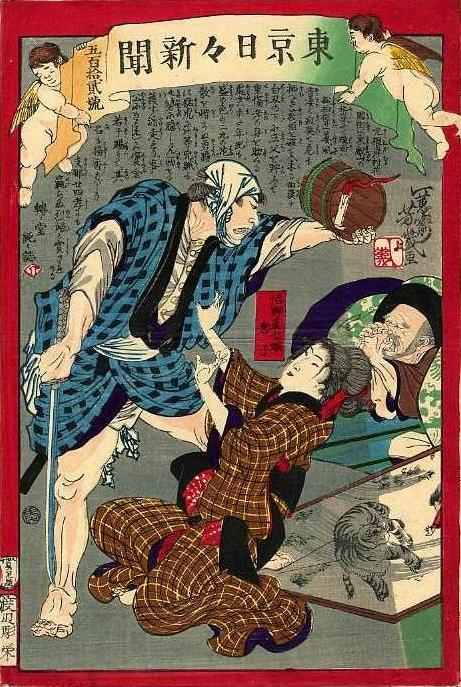

Figure 3: Suppression of "shinbun" (new tidings = news) on Ōsaka news nishikie Two examples of suppression of "shinbun" (news) on two chūban Ōsaka news nishikie. Names and addresses of writers and publishers also had to be disclosed with stamps on prints. | |

|

Figure 3a: "wa" pasted over "bun" "wa" pasted over "bun" to change "shinbun" to "shinwa" (new stories). Nichinichi shinbun (Daily news) No. 13b, mid 1875 (no seal). A merchant's signal to a maid who had promised to visit his room that night is intercepted and used by another guest at the inn. |

Figure 3b: Pigment of "shinbun" smeared Pigment of "shinbun" (news) but not "shi" (paper) smeared. Ōsaka nishikiga nichinichi shinbunshi (Ōsaka nishikie daily newspaper) No. 33, mid 1875 (no seal). Burglars are scared off when the master of the house recites a poem. Based on a story from Hōchi No. 535 (1874-12-15). |

|

|

TNS and YHS news nishikie

In this article we will present six stories selected from the two largest Tokyo news nishikie series -- Tōkyō nichinichi shinbun, or TNS, and Yūbin hōchi shinbun, or YHS. These nishikie are not to be confused with the newspapers whose names they bear, which are here called Tōnichi and Hōchi. In other words, TNS and YHS are nishikie, and Tōnichi and Hōchi are newspapers.

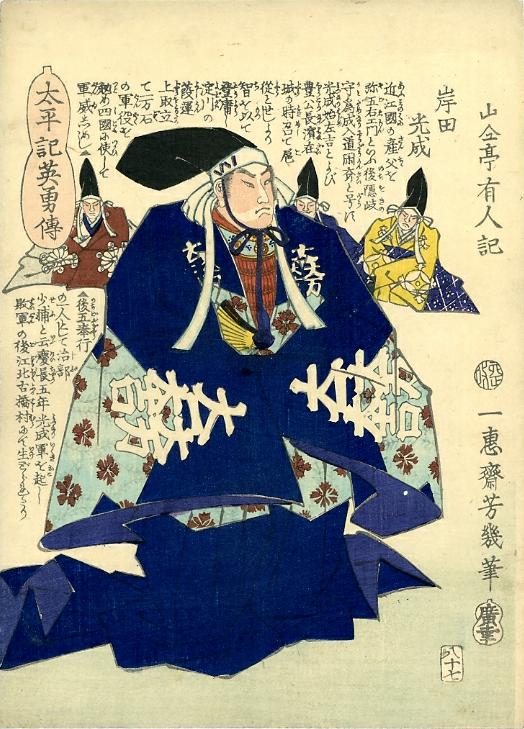

Over 100 TNS prints were published by Gusokuya between August 1874 and August 1875. Some were reprinted by Tsujibun. All prints in the main series were designed by Yoshiiku, mostly with text written by Takabatake Ransen, who usually signed his stories as Tentendō Shujin or Tentendō Dondon, and by Jōno Denpei, who generally signed his work Sansantei Arindō. Both were writers of fictional stories who also engaged in journalism and editing. Yoshiiku and the writers, although Tōnichi employees, freelanced for Gusokuya and other publishers. Most blocks were carved by Watanabe Horiei or Katada Horichō.

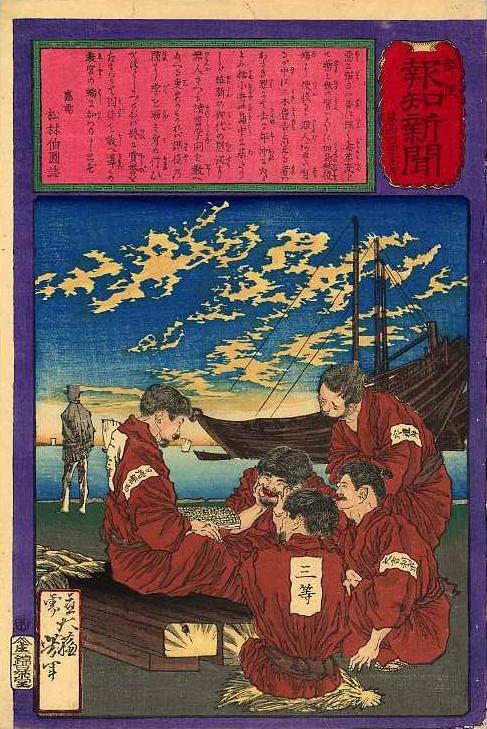

About 60 YHS prints were published by Kinshōdō between February and December 1875. All were drawn by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839-1892), some with the assistance of (if not entirely by) his student and employee Toshimitsu (our tentative reading of the name on the prints). The most prominent writers were Shōrin Hakuen (1834-1905), a narrator and actor, and San'yūtei Enchō (1839-1900), a rakugo storyteller and writer. Most were carved by Horita or Horigin.

Yoshiiku and Yoshitoshi were students of Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1861). They were rivals in a publishing world that was competitive yet also like an extended family. Both artists had known, and worked with, all the principal TNS and YHS writers since the 1860s and early 1870s, producing both nishikie stories and illustrated story books. Even while TNS and YHS were being published in the mid 1870s, they were working with the same publishers and even carvers.

Watanabe Horiei carved and Shōrin Hakuen wrote the stories for Yoshitoshi's Meiyo shindan (New tales of honour) series, which Gusokuya published in late 1874 while bringing out the TNS print series. The Meiyo prints were among many others that sought to profit that year from public interest in memorializing those who died in the wars that gave birth to the Meiji era in 1868, including the battle at Ueno. Both Watanabe Horiei and Katada Horichō carved some of Yoshitoshi's YHS drawings for Kinshōdō while also carving Yoshiiku's TNS drawings for Gusokuya.

Newspaper and nishikie literacy

Japanese is usually written in a mix of two scripts, kanji and kana. Kanji are Chinese characters, some created in Japan, used to represent Japanese words of Chinese, Japanese, and other origins. Kana are standard abbreviations of Chinese characters used to represent the morae, or basic sound groups, of Japanese. A word like ikken'ya has five morae (i+k+ke+n+ya) but only three syllables (ik+ken+ya). Morae, not syllables, are significant in Japanese poetics.

Kanji literacy requires a few years of education. Kana literacy can be achieved in a matter of days, much faster and more easily than alphabetic literacy in English, for example. Most early Meiji newspapers were written for people with fairly high levels of kanji literacy. Articles contained many kanji and readers were expected to know their pronunciations and meanings. Only later did more readable papers, with fewer kanji and more kana readings with the kanji, appear.

Nishikie generally used fewer kanji and often featured furigana, or kana written beside kanji to indicate their meaning through their pronunciation. The stories were also told in the more vernacular styles preferred by their writers, typically authors of popular fiction and orators of humorous tales.

The kana beside the kanji on the news nishikie we have translated show how they were meant to be pronounced in order to facilitate the metre of the narrative. For stories were written not only to entertain and nurture the heart, but to please the mouth and delight the ear.

As a language, Japanese can accommodate any degree of brevity, clarity, and levity. For the most part news nishikie stories are told in a brisk and crisp style with plenty of humour. Their plots are well developed and their narratives are laced with wordplay and allusions to familiar tales and literature. Many are minimalist to a fault and could serve as models of excellent storytelling in any language today.

Note on translations and romanisation

News nishikie can still be read today with the same sense of excitement, delight, horror, pathos, sorrow, titillation, and amusement that moved the people who bought them fresh off their blocks, still smelling of pigment, and read them, perhaps aloud. In this sense they remind us how little human nature has changed, despite our ability today to share our images and translations of them, at the speed of light, all over the world.

Our aim in translation is to convey the metaphors and phrasing of the stories as they were originally told. We have therefore strived for English that stays as close to the Japanese narrative as possible and is understandable without being too awkward.

(Parentheses) show Japanese expressions and/or additional meanings based on the original text. [Brackets] show either clarifications and explanations not in the original, or meanings of Japanese words that have been romanised rather than translated. Other than in titles of publications, and in quoted materials using italics, italics are used in this article only to mark katakana words and other instances where there is foundation in the original text for such highlighting. Otherwise all Japanese words are treated like English words.

The numbers on TNS and YHS prints indicate the issues of Tōnichi or Hōchi from which the stories on the prints were taken and not the order in which the prints were published, sometimes weeks, months, even years after the paper. The "a" and "b" designations differentiate prints that have the same number because their stories appeared in the same edition of the paper. These designations follow Tsuchiya 2000 (see acknowledgements).

Our term "news nishikie" (ニュース錦絵 nyuusu nishikie) includes both "nishikie shinbun" (錦絵新聞 "nishikie news"), probably the most common expression in their time, and "shinbun nishikie" (新聞錦絵 "news nishikie"), another contemporary expression. Our term also conflates "nishikiga" (錦画) and "nishikie" (錦絵), in which "ga" (画) and "e" (絵) represent different kanji that are both pronounced "e" after "nishiki" (錦).

We have romanised the kanji differently because it is important to distinguish prints entitled Ōsaka nishikiga shinbun (大阪錦画新聞) from others entitled Ōsaka nishikie shinbun (大阪錦絵新聞), though both would be read "Ōsaka nishikie shinbun" and be translated "Osaka nishikie news".

Dog with woman's head (TNS 865a)For this first story only, both the newspaper and nishikie accounts are presented, in order to show how news nishikie stories often differed from their newspaper sources. Newspaper version of "Dog with woman's head"

Commentary on newspaper versionThere are no full stops, commas or paragraph breaks in the original. The full stops in the translation correspond to breaks marked in the original by terminal conjugations. The aims and styles of the introduction to Takachiho and the account of the murder are different. The introduction, in a series of short statements, describes the people of Takachiho as formed by their harsh isolation from the benefits of social organization made possible by good government. As we shall see in the next story, a similar standard of geographical determinism was used to judge some Taiwanese. The description of Hyūga as "now within the jurisdiction of Miyazaki prefecture" reflects the fact that the Miyazaki prefecture was created just the year before -- but not for long. In 1871, when domains ruled by samurai clans were nationalised as semi-autonomous prefectures under appointed governors, Hyūga became Mimitsu and Miyakonojō prefectures. These were combined into Miyazaki prefecture in 1873. Miyazaki was merged into Kagoshima prefecture in 1876 and again became a prefecture in 1883. These changes reflect the instability in local politics that precipitated the Seinan War of 1877. Some of the fiercest battles of the war were fought around Takachiho, which sided with Saigō Takamori. The story of the murder is told in three long objective breaths without moralizing. Today a crime reporter would begin with time, place, and discovery of the body, then reveal the background and investigation, more in the manner of an Agatha Christie mystery. This story, however, is told in real time, more like a Lieutenant Columbo drama in which we watch a crime develop from its motivation to commission, then segue to the finding of the body, investigation, and arrest. |

||||

Nishikie version of "Dog with woman's head"

Commentary on nishikie versionThe cartouche identifies the man as "Farmer Gitarō of Takachiho village". The nishikie version frames the story very differently, to accommodate both some wordplay and the conclusion. Unlike the newspaper article, the nishikie story calls Takachiho the "vestige of the age of the gods" -- telling those who may have forgotten, or never learned, that Takachiho was the place where the Sun Goddess Amaterasu arrived and created the Yamato nation, according to Japan's oldest legends. This laid the foundation for the didactic observation at the end -- typical of nishikie stories, but not of newspaper articles. The ending appears to allude to a well-known line from the Analects (C. Lúnyŭ, J. Rongo), which many people would have studied when learning to read. "The Master [Confucius] said, The virtues [moral powers] of the middle way [moderation] indeed extend everywhere." Onkokudō just substituted "land of the gods" for "middle way" -- and replaced "extend everywhere" by a concrete example of Heaven's omnipresence. Narrative style of nishikie storiesSome news nishikie stories are written in segments of one or more couplets of 7/5 or so morae -- although one would never know this just from looking at the text. This, too, underscores the oral foundation of written narratives. The text of this story is separated by 26 periods into 27 segments, many of which are phrases rather than sentences. The following 5 segments consist of 7 couplets.

There is some wordplay in the narrative, such as "arashi" in the last segment of the above passage. It is written with a kanji meaning "windy and stormy mountainous climate" and furigana reading "arashi". On the surface "arashi yori" means "due to the severe mountainous conditions" and explains why Gitarō was able to do what he did. But anyone who heard or read "tare shiru hito mo" (someone who knew) would expect "nashi" or "araji" (does not exist) to follow. As distinctions like "shi" and "ji" were often not marked in writing, readers were accustomed to recognizing intended readings from context, and listeners too would readily have caught such a pun. |

|

|

|

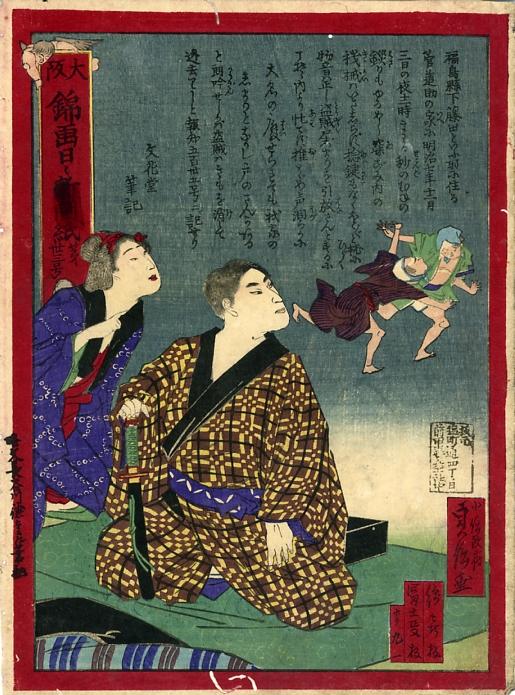

Figure 4a: Officers at scene of robbery Officers at scene of robbery and murder of former samurai. Nichinichi shinbun No 7, chūban published mid 1875 (no seal) by Watamasa, drawn by Sadanobu II, carved by Kyūichi, written by Kagen (Sadanobu II), no source for the story. |

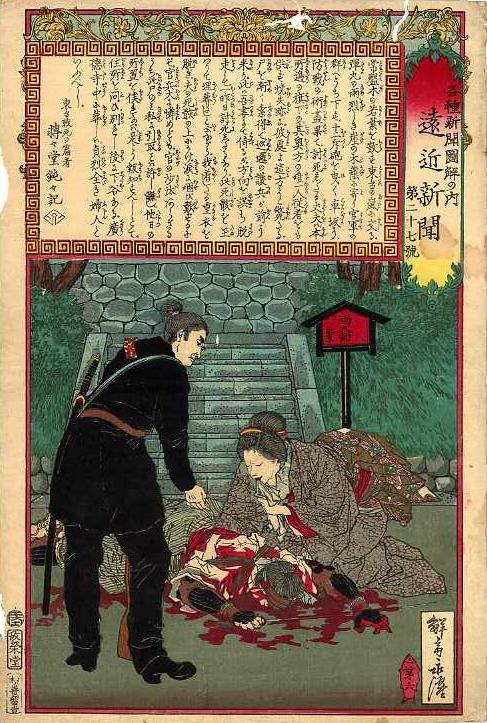

Figure 4b: Daughter protects father Daughter protects father from attack by robber. Tōkyō nichinichi shinbun, TNS No. 512, ōban published 1874-10m (seal) by Gusokuya, drawn by Ikkeisai Yoshiiku, carved by Watanabe Horiei, written by Tentendō Dondon [Takabatake Ransen], based on a story from 1873-10-22 Tōnichi. |

One majestic fold (TNS 726)Story

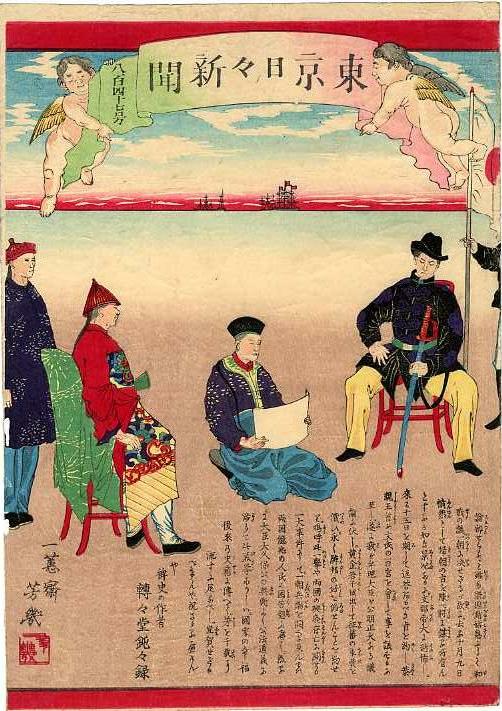

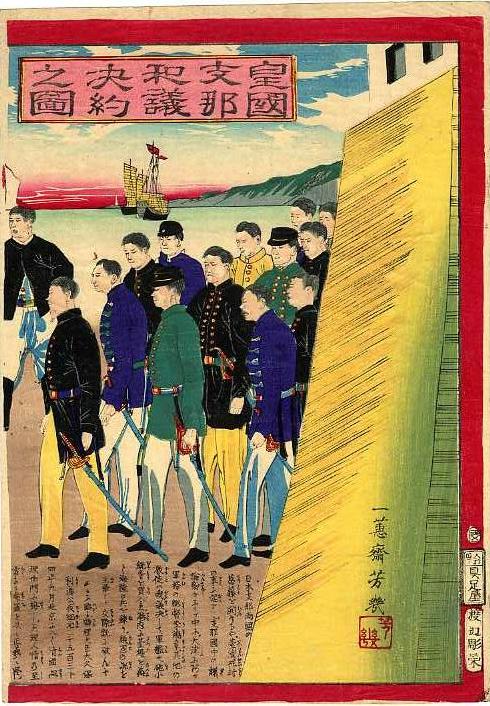

CommentaryThe cartouche reads "Taiwan Botan maiden". The story is full of the sort of euphonic and semantic wordplay that characterises such narratives. The most notable here are "hatsukagusa" / "koto no ha no hadzukashi" and "yae" / "hitoe" / "yashio". Both the flower and the place are written with kanji which are read mŭdān and mean peony in Chinese today. The writer has shown different pronunciations -- "botan" (hiragana) for the flower, "bootan" (katakana) for the place. The "n" in "bootan" is pronounced "ng", and in fact on some maps the place was written "Bootang". Botan village (J. Botansha, C. Mŭdānshè), on the southernmost peninsula of Taiwan, was the object of a Japanese expedition in the spring of 1874 to punish villagers who had massacred over fifty shipwrecked Ryūkyūan (Okinawan) fisherman in 1871. The expedition was led by Saigō Takamori's younger brother, Saigō Tsugumichi (1843-1902), the general who gave the girl the simple kimono. The first goal of the Meiji government was to nationalise the provinces and peripheral island groups like Ezo (Hokkaidō), the Ryūkyū Kingdom (Okinawa), and the Bonin (Ogasawara) and Volcano (Iwojima) islands. Taiwan, Karafuto, and Korea became part of Japan's sovereign domain through treaties concluded between 1895 and 1910. The verb "hirakeyuku" means to open out, settle, cultivate, and otherwise develop or civilise a territory and its people. It is the Japanese equivalent of the Sino-Japanese term "kaika" in "bunmei kaika". Benignly translated, this slogan defined the "civilisation and enlightenment" the Empire of Japan sought to bring to its homelands and neighbours. Now imperial benevolence was spreading to Taiwan to civilise tribes that China, though claiming the island, had not been able to hold accountable for their acts. Kishida Ginkō (1833-1905), Tōnichi's most flamboyant reporter, who had helped James Hepburn (1815-1911) edit his famous Japanese-English dictionary in Shanghai in the late 1860s, accompanied the expedition to Taiwan. His numerous dispatches appeared in the paper and inspired a number of TNS prints. Eight of the 108 prints in the main TNS series are about the Taiwan Expedition. Of the four triptychs in the main series, three involve this expedition. The prints cover all aspects of the war -- the battle with Botan tribesmen, efforts to cultivate the villagers and other natives after the fighting, negotiations with the Qing government in Beijing, and waving the flag in celebration of the diplomatic settlement. One even shows Kishida being carried across a stream by a native man. The drawing and story on TNS 726 were inspired by a number of Tōnichi articles that came out during June 1874, when the girl's village was attacked and she was captured. An article in the 26 June 1874 edition of Tōnichi (No. 726) includes this description.

The Peony girl was brought to Tokyo for a few months from mid 1874 to show the public what the Taiwan Expedition had been all about. This print was not published until October, shortly before she was taken back to Taiwan. |

|

|||

|

Figure 5b: China conciliation treaty Japan and China sign 1874 treaty resolving Taiwan issues. Tōkyō nichinichi shinbun, TNS No. 847, ōban triptych published 1874-11 (seal) by Gusokuya, drawn by Ikkeisai Yoshiiku, carved by Watanabe Horiei, written by Tentendō Dondon [Takabatake Ransen], based on a story from 1874-11-9 Tōnichi. |

Raking fallen leaves (TNS 689)Story

CommentaryReading this story is like hearing a pure fundamental which lacks the harmonics that give natural sounds their tonal qualities or colours. Takabatake knew that those who saw this nishikie would resonate with his narrative. They would recognise the names in the two cartouches -- Amano Hachirō (1831-1868) and Nakamura Tokusaburō. They would recall the tensions that had gripped Edo in the days leading up to the battle at Ueno, just weeks after the arrival of the coalition of samurai who had defeated the Tokugawa army in Kyoto, sent the last shogun packing to Mito, and started a new government sanctioned by the emperor. They would have known that, despite the peace that had come with the start of the Meiji era, the civil wars were not quite over. And there were reports of battles in Taiwan, wherever that was. Some would have been among the throngs of well-wishers at Ueno on 15 May 1874. Or the following day they may have read in Tōnichi about the groups that had offered funds to "condole the spirits under the [yellow] springs (senka / izumi no shita) [underground world of the dead]". First listed was the Kishōza in Hamachō, which contributed 25 yen in gold. This kabuki theatre, built just the year before, was the forerunner of the Meijiza in Nihonbashi Hamachō in Chūō ward today. The Tōnichi article went on to note that Takabatake Ransen and Maeda Natsushige had been seen at Ueno on the 15th. They had written an "unusual book" called Matsu no ochiba [Fallen leaves of Pines], or Tōdai senki [Eastern heights war chronicle], of stories about the heroes. The writers had brought together their hands at the [memorial] service [in thanks] that they "had already received permission and publication was near." Many people, still reckoning time according to the lunar calendar, officially abandoned after 1872, would have recalled that the battle of Ueno hills did not occur on "15 May" but on the morning of the 15th day of the fifth month of the fourth year of Keiō, or Boshin, a lunar calendar date corresponding to 4 July 1868 on the solar calendar. On the morning of this early summer day, in the mist of a warm seasonal rain, government forces commenced firing on holdouts at Ueno. What is now the park was then the Buddhist sanctuary of the Tokugawa clan, built to protect their political interests in Edo castle from demons to the northeast. By evening, the Shōgitai and others had been routed. Many were killed, and those not downed by bullets took flight. Some melted into the new order. A few joined remnants of resisters in places like Aizu-Wakamatsu. Amano was captured and died in jail that December. Many of the temples and about 1,200 homes in the area were burned. Fukuzawa Yukichi (1835-1901), a Bizen province samurai turned linguist-cum-educator, recalled that while the battle was raging he was giving his first lecture at his new Keiō Gijuku boarding school, now Keiō University. He remembered hearing the cannon fire, and that some of his students had climbed onto the roof and gazed at the smoke. Since 1957, Keiō University has somewhat unseasonably celebrated 15 May as Francis Wayland Day. For on that bloody morning of 1868, Fukuzawa and his students were reading The Elements of Political Economy by the American Baptist clergyman and educator Francis Wayland (1796-1865), an early president of Brown University. |

Gifted wife (TNS 1015)Story

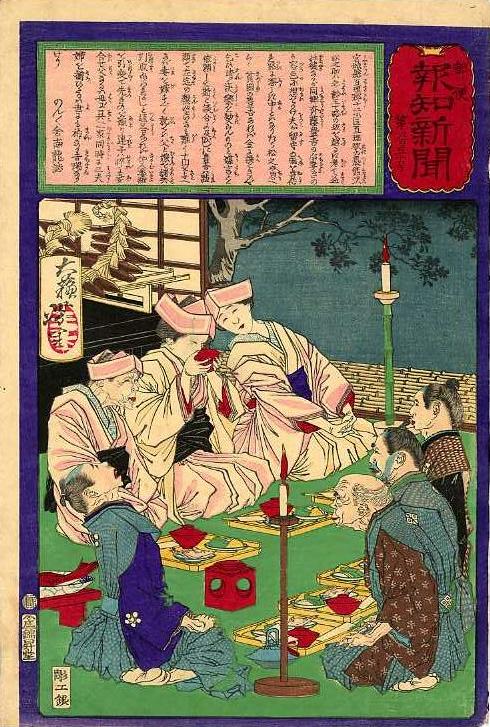

CommentaryShe was twenty two or three according to the original Tōnichi article. As the big sign in the drawing says, Rodayū was a seller of haraharagusuri, a popular remedy for all manner of gastrointestinal discomforts -- still made and sold today in Osaka. Anatomically "hara" means stomach or abdomen -- while "harahara" is an onomatopoeic expression for feelings of unease and fear, or for the sounds of burning or fanning, or of falling leaves, dew or tears, among similar conditions -- hence the wordplay at the end. Rodayū was the husband's stage name as a performer of jōruri -- epic ballads narrated on stage to the accompaniment of a string instrument. Tentendō uses gidayū, the Kansai term for jōruri, to rhyme with the husband's name. Performing gidayū became Rodayū's principal occupation. His wife's beauty made her more famous than the remedy handed down in his family. As Rodayū is presenting a guest in his home with a gift, he speaks to his wife's lover in terse but polite terms. The tension thus built is released with their eviction and tears -- which become the butt of two wordplays, one involving the name of the medicine, the other the unexpected (fukaku no) turn of their indiscretion (fukaku). Tentendō turned an ordinary newspaper account into a playful story suitable for oration -- told in 19 couplets divided into 12 segments translated here as 9. His own telling of the story has echoes of the chariba, or comical jōruri, that Rodayū might have told on stage. Shinbun zue (News illustrated), a news nishikie published in Osaka, featured the same story in its No. 38 issue. Unlike other prints in this series, No. 38 has no publisher, drawer, carver, or writer signatures. Its story is attributed to "Tōkyō nichinichi shinbun" and follows the newspaper account very closely. Its illustration shows a woman with noshi attached to her back, and a man with a cartouche reading Rodayū. The noshi in both drawings is an exaggerated version of the kind of small ornament that would have been attached to practically any gift formally given to congratulate or wish well. A typical noshi was made of strips of dried abalone that had been flattened and stretched to represent the spread and continuation of fortune. The strips were often wrapped in colourful papers as shown in the drawings. Today noshi are mostly printed images on paper attached to seasonal gifts, or on paper wraps or envelopes used to give money at weddings or graduations. |

Three generations marry (YHS 650)Story

The three-generation marriage story was widely circulated. The version told on this nishikie was based on an article in the 25 April 1875 edition of Hōchi. The story was also reported in the 6 May 1875 edition of Tōnichi (No. 1005). The Tōnichi article inspired another news nishikie version, Ōsaka shinbun nishikiga (Osaka news nishikie) No. 9, which attributes the story to "Nichinichi No. 1500" [sic]. The newspaper articles state that Matsunosuke had lost his wife the previous year. His mother was over 60 and not able to do all the cooking, and his son was 20. Toyokichi, a neighbouring farmer, was over 50 and poor, and Kino, his second wife, was still young. When they married, she had brought with her a daughter by her previous husband, and soon her father had also come to live with them. The Tōnichi article said that Matsunosuke had to pawn his rice paddies to raise the money. The two men exchanged statements in writing. People sighed with grief when the parents, children, and grandchildren married at the same time. The Osaka nishikie version concluded on a note that suggested why the witnesses sighed. After hearing repetitions of Takasago, a popular wedding song from the nō play by this name, they had to watch the san-san-ku-do (three-three-nine-times) ceremony, in which each spouse-to-be takes three sips of sake from each of three cups. |

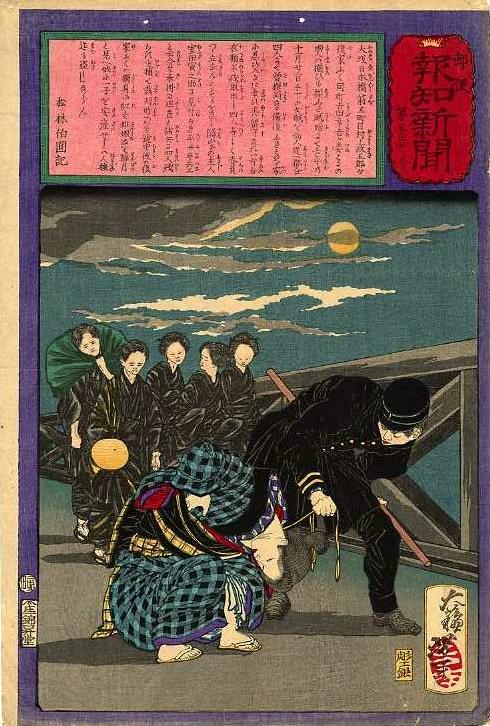

What the woman stole (YHS 527b)Story

CommentaryThe newspaper article said that Fuku had become pregnant "although she had no husband" (otto aru mi ni arazaredo), while Hakuen implied that a "single woman" (dokushin) was not expected to be pregnant. Neither version calls Fuku a "widow" (mibōjin, one who has not yet died) but refers to her as a "goke" -- her role as the woman Murakami left in this world to care for his family. Neither expression censures Fuku for not being forever faithful to her deceased husband, a standard of virtue applied to some but not all widows. The newspaper version compared the women to two female thieves of yore -- Mikazuki no Osen and Kijin no Omatsu. Since no violence occurred in the commission of the Osaka crime, such a comparison would appear to be undeserved. While neither version provides details of Fuku and her child's fate, magistrates during the time tended to be lenient with female offenders. Certainly Fuku was nothing like Omatsu, the legendary she-devil of northern Japan, who would entice a samurai to assist her in crossing a river then cut his throat, as depicted in Yoshitoshi's 1886 diptych. |