| Bibliography of news nishikie related publications | ||||

| Introduction | General | Stories | Drawings | Topics |

General topics

•

Nakae 2003

Crime

•

Arakawa 2007

•

Bessatsu Rekishi dokuhon 1988

•

Gretton 1980

•

Mertz 1997

•

Rekishi dokuhon1990

•

Rekishi dokuhon1991

•

Schreiber 1996

•

Schreiber 2001a

•

Yamashita 1988

Suicide

•

Asahi 1987

•

Brown 2001

•

Gates 1988

•

Komine 1935

•

Komine 1938

•

Komine 1940

•

Monestier 1997

•

Wetherall 1983

Society

•

Cooper et al 1971

•

Meech-Pekarik 1986

•

Miyatake 1997

•

Okazaki 1988

•

Yumoto 1999

Politics

•

Chaikin 1983

•

Eskildsen 2002

•

Eskildsen 2005

•

Kang 2007

•

Konishi 1977-1978

•

Tonichi 1928 (1970, 1983)

| General topics related to news nishikie stories |

Nakae Katsumi Includes a chapter on "The cost of information sources, kawaraban" (pp 69-72). One section discusses the changing prices of kawaraban during the Bakumatsu period, meaning the final decades of the Edo period (1600-1867). Kawaraban news sheets go back to at least 1615, and were generally called "yomimono" until the Bakumatsu period. The chapter also reviews a prohibition of suicide pact reportage in an effort to stem a contagion of love suicides in the early 18th century, and kawaraban coverage of the Ansei earthquake that killed 7,000 and seriously injured 2,000 Edoites, and destroyed some 14,000 homes in 1855. (MS, WW) |

| Crime |

Arakawa-ku Kyoiku Iinkai (editor) Forthcoming. (WW) |

Bessatsu Rekishi dokuhon (editor) Forthcoming. (WW) |

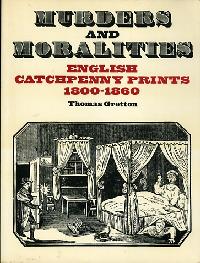

Thomas Gretton A very nice little survey of catchpenny prints in 19th-century England. The single-sheet ballads and broadsides were sold by hawkers and pedlars on city streets and at county fairs to entertain and inform the literate poor. The themes of their illustrated stories included murder, suicide, and execution, politics and religion, and morality. The author, a professor of art history, introduces over ninety examples to show the great variety of the prints -- some rather gruesome, others simply naive, bizarre, or comical. (WW, from blurb on back cover) |

John Mertz A fine introduction and analysis of how murder and other crimes were reported and tried in the early Meiji period, and the impact of such cases on Japanese literature. Several pages are given to the dokufumono (poisonous woman stories) inspired by cases in the late 1870s. He makes no mention of news nishikie, but the social milieu he describes is precisely that of news nishikie era. Mertz is a professor of Japanese at North Carolina State University. He specializes in the evolution of literature in the Meiji period and the relationship between literary change and the social history of the period. In one of his courses he explores how "Stories of love, crime, adventure, adolescence, and career success became imbued with new notions of democracy and nationalism." (WW) |

Rekishi dokuhon (editor) Forthcoming. (WW) |

Rekishi dokuhon (editor) Forthcoming. (WW) |

Schreiber, Mark Beginning with a serial rapist and murderer whose career began while American bombs were still falling on Tokyo in 1945, and ending with a doomsday cult's toxic nerve gas attack on the Tokyo subway that occurred while the book was being completed, this paperback covers 16 of Japan's most memorable crimes during the postwar period. Several incidents -- such as Japan's largest robbery up to that time, by a young man posing as a motorcycle policeman in 1968 -- remain unsolved to this day. Content is also devoted to how the vernacular media and other commentators reported on or analyzed the crimes, particularly in the sensational cases of ethnic Korean roughneck Kim Hee Roh and accused wife-killer Miura Kazuyoshi. Includes numerous rare photographs of the crime scenes. (MS) |

Schreiber, Mark From the Lord High Executioner (he really existed) to Nezumi Kozo -- a talented thief who stole from the rich, gambled it all away and was adored by the common people anyway -- this book covers 400 years of crime and punishment in Japan. Contents include introductions to famous lawmen and judges of the feudal era, including "Hei the Fiend," who headed the equivalent of old Edo's SWAT brigade; the difficulties in enforcing the nation's first ordinance against urinating in public; a demented cop who nearly assassinated the heir to the Russian throne; Japan's most famous Peeping Tom; and a deaf-mute serial killer who fantasized himself as a character in a samurai movie. Illustrated with numerous old woodblock prints and rare photographs. (MS) |

Yamashita Tsuneo Forthcoming. (WW) |

| Suicide |

Nihon no rekishi Number 69 Forthcoming. (WW) |

Ron M. Brown This is the finest study of the history of suicide in art, limited though it is to the art of Europe. (WW) |

Barbara T. Gates This thorough study of suicide in Victorian England includes some fine contemporary illustrations, mostly of women falling after jumping off bridges, not found in Brown 2001. (WW) |

Komine Shigeyuki, editor and publisher Komine Shigeyuki (b1883), a psychiatrist, pioneered the study of murder-suicides and romantic and other suicide pacts in Japan, and no one since him has quite matched the breadth and thoroughness of his research and writing on these subjects. (WW) |

Komine Shigeyuki (b1883), editor and publisher Forthcoming. |

Martin Monestier [J. Marutan Monesutie] This overview of methods in European suicide cases, past and present, is well illustrated with death scene photographs and depictions in woodcuts, engravings, oil paintings, and other graphic media. All manner of social predicaments, motives, and venues are represented. It is a good companion to studies that focus on suicide as a theme in just, say, art or woodcuts. Chapters include (1) How do people die?, (2) Why do they die?, (3) Who dies?, (4) Where do they die?, (5) Suicide and society, (6) Unfathomability, and (7) Riddles of history. (WW) |

William Wetherall This essay placed first in the specialist division of the Third Japanology Essay Contest Sponsored in November 1980 by the International Cultural Association of Kyoto with the support of The Japan Times and Matsushita Electric Industrial Company. A summary was read at a final screening on 15 January 1981 at Kyodai Kaikan in Kyoto. A slightly abridged version was published as "Anti-Suicide Traditions in Japan: Past and Present" in The Japan Times, 14 February 1981, pages 10-11. (WW) |

| Society |

Michael Cooper, Armichi Ebisawa, Fernando G. Gutierrez, and Diego Pacheco (edited by Michael Cooper) Given the religious nature of early political and economic relations between Japanese and Europeans, and the Jesuit backgrounds of most of the authors, this study naturally focuses on the history of early Christianity in Japan. Recognizing that art is an important part of their historical record, the authors make ample use of all manner of graphic material, black-and-white and color, to illustrate their narrative. In this sense, the book is incidentally an art history. (WW) |

Julia Meech-Pekarik This is a generally well organized and competently written overview of the Meiji period through woodblock prints. However, its focus on higher culture makes it less reliable as a guide to the popular and vulgar culture of news nishikie. Its brief remarks about Yoshiiku and the Tokyo nichinichi shinbun nishikie are rare in a book of this kind, and though they are among the most accurate they also mislead. Meech-Pekarik on Yoshiiku and

|

|

Illustrated serialized fiction already had a long history in Japan, but in the Meiji era even fledgling newspaper companies came to realize the commercial potential of this form. It is interesting to note that despite the obviously topical, newsworthy themes of Meiji prints, there was for a long time a strong prejudice against using woodcuts as newspaper illustrations; apparently they did not suit the rather lofty and high-minded tone to which most papers aspired. Only the smaller papers that catered to less literate audiences whose chief interest was entertainment and scandalous news felt free to indulge in such pictures, often of a comic variety. Between 1874 and 1881 a hybrid genre of single-sheet print called "color woodcut newspaper" (nishiki-e shimbun) occasionally depicted exciting events carried in contemporary newspapers. It included the title and date of the paper as well as a brief summary of the story, which was chosen as a model of virtuous conduct. Among the first of these was a picture by Yoshiiku based on an 1874 Tokyo nichi nichi shimbun article about a young girl who heroically saved her father from the murderous assault of an armed burglar. Yoshiiku was in fact associated with the Nichi nichi, and although these prints may sometimes have served as a colorful appendix in smaller newspapers, they were not published by the newspapers themselves. [Note 16] To the extent that the news media eventually began to hire staff drawers on a contractual basis, the illustrations most in demand were pictures of celebrities and highlights from recent sumo matches. That is not to say that newspapers initially favored photographs over prints, however. It was not until the 1880s, on the occasion of the eruption of Mt. Bandai, that the Yomiuri shimbun (founded in 1874) dispatched its first photographer, but even then cumbersome technical difficulties prevented this medium from coming into general use until some years later. Note 16. Some nishiki-e shimbun arbitrarily attached the names of nonexistent newspapers. See Higuchi [Hiroshi], Bakumatsu Meiji no ukiyo-e shusei [(Compilation of Bakumatsu and Meiji woodblock prints), Tokyo: Mito Shoya, 1955], 61. Yoshiiku's publisher was Fukuda Kumajiro, and his print is illustrated and discussed in The Far East, September 30, 1874. |

Meech-Pekarik begins the cited paragraph with a reference to woodcut illustrated fiction, and ends it with a remark on the start of photographic journalism. Between these continents is an ocean of commentary, which I have highlighted in purple, that is unrelated to either illustrated fiction or photographic journalism.

Vague correctness

Meech-Pakarik gets a few things right, though her correctness is vague. Not only did the newspapers not produce the prints, but the Tokyo nichinichi shinbun nishikie drawn by Yoshiiku do not appear to have been the brainchild of Tonichi, the newspaper. He was, for sure, "associated" with the paper, as he was one of the founders of Nipposha, which published Tonichi, and he oversaw the printing of the early issues of the paper.

But Yoshiiku did something for Tonichi that upsets what Meech-Pakarik would have us believe about woodcuts in early Meiji papers. Ironically, Tonichi epitomized the very sort of "lofty and high-minded" rag she claims would not have been interested in woodcut illustrations. Yet very first issue of this very literate paper ran a story about a murder that two years later was featured in one of Yoshiiku's Tonichi news nishikie. And right in the middle of the one and only page of this very first issue of Tonichi the newspaper, between the heavy Japanese and dense kanbun, was a woodcut illustration by Yoshiiku.

Eiri shinbun

It is also ironic that, had Meech-Pakarik stayed on the topic of serialized fiction, she would have had to write that this very same Yoshiiku, with other Nipposha founders and employees, started Hiragana eiri shinbun, later renamed Tokyo hiragana eiri shinbun and then Tokyo eiri shinbun, which became one the most popular illustrated newspapers of the Meiji period.

The masthead of the earliest issues of Eiri shinbun (for short) was designed by Yoshiiku. It featured the name of the paper in a banner unfurled by cherubs -- in the manner of the Tonichi nishikie and many of its copycats. Yoshiiku, of course, was only imitating himself, since he had just recently been designing the Tonichi nishikie -- and in fact he seems to have been the first to use Cherubs and Banners on woodblock prints in Japan.

Serialized fiction

More relevant to Meech-Pakarik's remarks about illustrated fiction, though, is the fact that, in 1878, Eiri shinbun began serializing a fictionalized version of an actual incident called "Kinnosuke no hanashi" (Story of Kinnosuke). This is thought to have been the start of serialized newspaper fiction in Japan. And every episode was illustrated by at least one woodcut, very likely drawn by Yoshiiku.

Meech-Pakarik's endnote (Note 16) also includes misinformation. Some news nishikie series bore the names of the newspapers that served as their story sources -- Tokyo nichinichi shinbun and Yubin hochi shinbun in Tokyo, for example. Others, like Osaka nichinichi shinbun and Nichinichi shinbun in Osaka, had no namesakes, as there were as yet no local dailies in the Osaka area where they circulated. Such news nishikie carried local stories but also took stories from Tokyo newspapers, such as TNS and YHS. When recycling a story from a Tokyo paper, the name and issue of the source were often noted on print. There was nothing "arbitrary" about the naming of such woodcuts, which in effect were newspapers. Hence the distinction made by Tsuchiya Reiko and others between shinbun nishikie (news nishikie which took the names of newspapers), and nishikie shinbun (news nishikie which bore distinct names and were circulated in lieu of newspapers).

Have brushes, will travel

It is also misleading to say that Yoshiiku's publisher "was" Fukuda Kumajiro. Yoshiiku was a free lance designer. For sure, Fukuda published some of Yoshiiku's work, including (as Gusokuya) the Tonichi news nishikie. But major designers like Yoshiiku and Yoshitoshi "had brushes and traveled" so to speak.

John Black Reddie and TNS-512

The 30 September 1874 issue of The Far East, a photo-illustrated newspaper published in Yokohama by the Scottish British Australian journalist John Black Reddie, is said to have carried the first news report in English about the Tokyo nichinichi shinbun nishikie series (Tsuchiya 2002:105). The article in question, entitled "Art in Japan", introduced TNS-512, the Tonichi nishikie which shows and tells how Kurako defended her father Amano against robbers (Tsuchiya in Kinoshita and Yoshimi 1999:104, n5). (WW)

Miyatake Gaikotsu This pocketbook edition is not of the original collection called Meiji kibun but is a selection of anecdotes from a number of Miyatake's works, including the work that originally bore this title, a collection of articles he wrote between January 1925 and June 1926). This edition uses present-day forms of characters and kana orthography, bold face to stress what in the original would have been marked with ticks beside the graphs, and brackets to enclose commentary. Country folk worshipping NipposhaMiyatake tells a very amusing story he calls "Nipposha o ogamu inakamono" [Country folk worshipping Nipposha], about people from the country who knelt on the ground and prayed before the two-story Nipposha building, a landmark of Meiji civilization and enlightenment in Ginza, because they thought 日報社 (Nipposha) was 日枝社 (Hiesha), which they equated with 日枝神社 (Hie Jinja) in Nagatacho. Apparently an old man sat at the entrance of the Nipposha building and sold good-luck charms. Yoshitoshi poked fun at this in one of his Tokyo kaika kyoga meisho [Famous places in comic pictures of the enlightenment in Tokyo], a parody print published in 1877, according to Miyatake (p 180). Other prints in this series were published as late as 1881. Nipposha was the publisher of Tokyo nichinichi shinbun and, by then, Tokyo eiri shinbun. Newspapers as Tokyo souvenirsMost interesting for us, however, is a story called "Tokyo miyage to shite no shinbunshi" [Newspapers as Tokyo souvenirs]. It runs two full pages and is worth translating in its entirety (pp 181-182). See also the review of Higuchi 1962.

This is a very dynamic view of nishikie in general and news nishikie in particular during the early Meiji period. It is easy to understand why Ono Hideo might have been attracted by it -- and puzzling why Tsuchiya Reiko did not give it more attention in her citicism of Ono's contention, possibly inspired by Miyatake, that all news nishikie were souvenirs, not news. See TNS Souvenirs to News under articles for further details and discussion. (WW) |

Okazaki Masao Subtitled "Stars of the angry spirits and strange legends," this book provides a useful overview and brief introductions to Edo's best known ghoulish apparations as depicted in Tokugawa and Meiji Period art. Contains over 30 pages of color plates, including numerous works by Yoshitoshi. Also includes several undated samples from the "Honjo Nanafushigi" [Seven strange wonders of the Honjo district] by Okada Kuniaki (岡田國輝). (MS) |

Yumoto Koichi (compiler) Actual reports of ghostly sightings, apparitions, and other paranormal phenomena as reported in vernacular newspapers (including several nishikie newspapers) between 1872 and 1900. Eight pages of color plates at front include two from Tokyo nichinichi shinbun (Nos. 445 and 1055) and one from Osaka Nichinichi Shinbunshi (Number 8). (MS) |

| Politics |

Nathan Chaikin 66 color and 55 black-and-white illustrations, maps, and bibliography. Illustrates the various episodes of the Sino-Japanese mainly through woodblock prints, mostly triptychs. The introductory text gives information on the war, and on the drawers and prints. Artists include Adachi Ginko, Kobayashi Kiyochika, Kunimasa IV, Kuniteru III, Ogata Gekko, Toshiaki, Toshihide, Toshikata, Toshimasa, Toshimitsu, Watanabe Nobukazu, and Yoshu Nobuyasu, among others. (WW) |

Robert Eskildsen The Taiwan Expedition of 1874 was the biggest single story in Japan at the time the Tokyo nichinichi shinbun nishikie were being published. Eight of its 114 prints deal with this war, based on stories reported to the Tonichi paper by Kishida Ginko, a Tonichi reporter who accompanied Saigo Tsugumichi's forces to the Taiwan and the Botan mountains where Saigo's forces clashed with villagers in the Battle at Stonegate. Japanese forces had been involved in wars on the Korean peninsula in the early centuries of the first millennium. Hideyoshi, in the last decade of the 16th century, invaded Korea supposedily as a first step to conquering Ming China. And there were other instances in which nominally "Japanese" forces engaged in military operations outside nominally "Japanese" territory -- such as actions against Ainu in Ezo. Depending on how one defines "Japanese" and "Japan" -- the expedition that somewhat unofficially went to Taiwan in 1874, to deal with native inhabitants who had murdered some 54 shipwrecked Ryukyu fisherman and crew in 1871, marked the first time in nearly three centuries for such a large contingent of Japanese to deploy outside Japan in order to conduct military and other operations -- and, in fact, most operations carried out in Taiwan by Saigo's army were not military. Whether Saigo's army was "Japanese", and whether it was "sent" to Taiwan by "Japan", are disputable. If consequences are more important than intent and process, however, there is no doubt that, as a result of what happened between 1871 and 1874, "Japan" established a "Japanese" presence in Taiwan that may be characterized as "colonial". Eskildsen and news nishikieThese musings about "Japan" and "Japanese" are mine. Robert Eskildsen, an historian who seems to be making the Taiwan Expedition his life work, acknowledges that Saigo, against the wishes of the government, went to Taiwan on the strength of a previously issued imperial order. Otherwise he does not equivocate about what Saigo's forces represented, or in whose service they went to Taiwan. He argues, not unconvincingly, that the expedition had "colonial intent" from the very beginning. Eskildsen's paper is a finger-exercise for a book he is writing on the expedition, and hence it should be read as a work in progress. It is particularly worth reading for us because Eskildsen introduces some of Yoshiiku's Tokyo nichinichi shinbun nishikie on the Taiwan Expedition, and also Yoshitoshi's Taiwan shinbun nishikie, and compares Yoshiiku's and Yoshitoshi's depictions of the Battle at Stonegate. He also shows one of many woodcuts Sensai Eitaku drew of the Taiwan Expedition for Murai Shizuma's Meiji Taiheiki -- in particular, a cannibal print, reportedly from Volume 8, which I have not seen.

This review is based on the web edition in the History Cooperative database. (WW) |

JAS issue focusing on colonialism in Taiwan The Journal of Asian Studies Once in a while an issue of an academic journal contains more than one article that is worth reading. This has five, beginning with Robert Eskildsen's excellent introduction to the other four. Taken together, they contain a enormous amount of interesting detail -- not just detail, but detail that is pressed into the service of understanding the human complexity of Taiwan's political history. Even the footnotes are fun. (WW) Robert Eskildsen Andrade, Tonio Barclay, Paul D. Tavares, Antonio C. Katz, Paul R. |

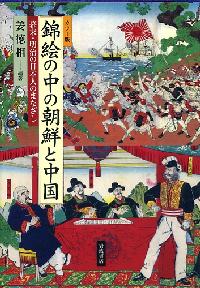

Kang Duksang, compiler and author, et al Among the most interesting books that feature woodblock prints are those that focus on social or political themes -- hot springs, fire fighting, illness, sumo. This book is about the relationships between Japan and Korea and China -- as and contemporary -- as portrayed in pictures drawn and published during the final decade or so of the Edo (Tokugawa) period, through most of the following Meiji period -- roughly the half century between the arrival of Commodore Perry in 1852-1853 and the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905. Kang divides the prints -- selected from many more like them -- into five groups reflecting the nature of the conflict they concern -- whether "castigation" (征伐 seibatsu) of Korea by Japan, "disturbance" (暴動 bōdō) by Koreans, or "war" (戦争 sensō) between Japan on one side and Korea, China, or Russia on the other.

These sections are followed by illustrated articles on related topics by Okubo Jun'ichi, Inoue Katsuo, and Mitani Takashi -- specialists in, respectively, Edo and Meiji art, Bakumatsu and Meiji Restoration history, and modern Chinese history. Kang DuksangKang Duksang (姜徳相 カン・ドクサン) was born in Chosen (as Japan called Korea after it became a Japanese territory) in 1932. As he graduated from Waseda University in 1955, he was probably in the prefectures with his parents at the end of World War II in 1945. As such he lost his Japanese nationality in 1952 when the San Francisco Peace Treaty came into effect. Kang, an academic historian, is a professor emeritus at Shiga Prefecture University. Most of his writing has been about early modern and modern Korean history, with some focus on Korea and Japan, and Koreans in Japan. He speaks from the position of a "first generation" Korean in Japan. Kang's present nationality is not clear. However, he has been closely associated with Zai Nihon Dai-Kan Minkoku Mindan Chuo Honbu [Korean Residents Union in Japan], which is affiliated with the Republic of Korea. And he was one of the founders of Zainichi Kanjin Rekishi Shiryo Kan [The History Museum of J-Koreans], located in Mindan's headquarters in Minami Azabu, Tokyo. (WW) |

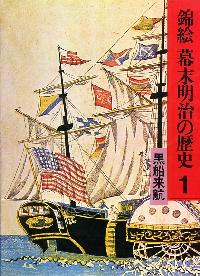

Konishi Shiro An very comprehensive collection of nishikie grouped and presented to illustrate Japan's social and political history during the final years of the Tokugawa period and throughout the Meiji period. All but a few pages at the back of each book are in color. Most of the prints are shown in their entirety, and all have captions identifying the title, drawer, and date if known, plus a comment about the theme. (WW) 1. Black ships arrive 2. Opening of Yokohama port 3. Uprisings at end of Tokugawa period 4. Civil wars leading to Restoration 5. New Meiji government 6. Civilization and enlightenment 7. Rebellion of disenfranchised samurai 8. Seinan War 9. Rokumeikan era 10. Promulgation of Constitution 11. Russo-Japanese War 12. Before and after Russo-Japanese War |

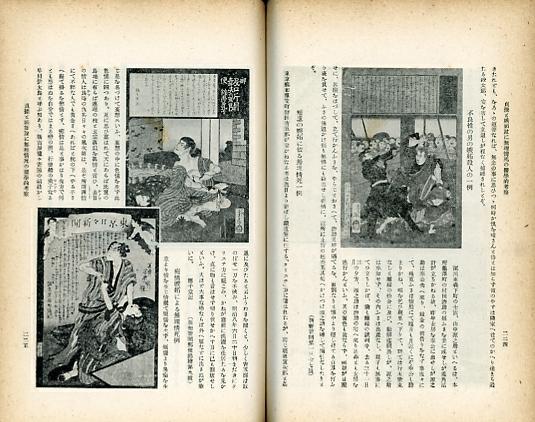

Tokyo Nichinichi Shinbun, Shakaibu The two volumes shown to the right, though their content is somewhat different, are both more recent editions of a book first published in 1928 by Marikaku Shobo. The book is a collection of articles serialized in Tokyo nichinichi shinbun from late in 1927 and published in January 1928. Boshin was the sexegenary name of the year 1868, when the Tokugawa shogunate was toppled and the emperor was restored as the formal sovereign of Japan. 1928, being just 60 years later, was also a Boshin year, as was 1988, the year of this 9th reprinting of the paperback. The 1970 edition came out roughly one century after the start of the Meiji period. Both volumes include somewhat different illustrations of contemporary materials. The more 1988 bunko edition includes a couple of news nishikie, and ends with an essay by film critic Sato Tadao called "'Boshin monogatari' no omoshirosa" [What is interesting about "Boshin monogatari"] (pp 277-290). The "Boshin monogatari" itself consumes about one-third of the book (1970 edition pages 15-93, 1988 edition pages 9-106). This is divided into two parts, the first covering the Toba-Fushimi War in Kyoto from the 3rd day of the 1st month of Keio 4 (27 January 1868), through the Ueno War involving the Shogitai in Edo on the 15th day of the 5th month (4 July). Tokugawa Yoshinobu, who had been with his regiments in Kyoto when they were defeated, returned to Edo and surrendered the castle to the restorationist government, which had been formed in Kyoto and came to Edo to take control of the shogunate. Tokugawa took refuge for a few days in the family temples at Ueno, then retired to his clan residence in Mito with the understanding of the new government. Tokugawa loyalists calling themselves the Shogitai remained at Ueno, and other groups and individuals opposed to the restoration government also gathered there. Within weeks they were confronted and quickly defeated by government forces. Another third of the book is given to a look back on life "Go-ju-nen mae" [Fifty years ago], meaning the first decade of the Meiji period, including the Seinan War of 1877, the last of a series of rebellions and wars that are all part of the "Tales of Boshin". The final third, called "Ishin zengo" [Before and after the Restoration], consists of separate chapters on the town magistrate offices (machi bugyosho) that figured greatly in the fairly orderly transition from shogunate to restorationist authority, and on the two largest groups of Tokugawa allies and defenders, Shinsengumi and Shogitai. The 1988 bunko includes full-page black-and-while images of Yoshitoshi's Meiyo shindan drawing of the Shogitai warrior Oka Jubee (p 68), and Yoshiiku's Tokyo nichinichi shinbun nishikie No. 988, depicting a newspaper account of an 1875 incident in which a man attacked an actor on stage for his excessive parody of Kakezara in the story of Benizara and Kakezara. (WW) |