Soshi kaimei myths

Confusion then, misunderstanding now

By William Wetherall

First posted 25 June 2007

Last updated 14 October 2023

Setting the stage

In brief

•

Nationalization

•

Chosen registers

•

Governors-general

•

Legal integration

•

Racial assimilaltion

•

Timing

Name-change policy

•

Intentions

Operation

•

Resistance

•

Compliance

•

Legacy

•

On Korean time

1939 decrees and ordinances

Sources

•

Translations

•

Decree 19

•

Decree 20

•

Ordinance 221

•

Ordinance 222

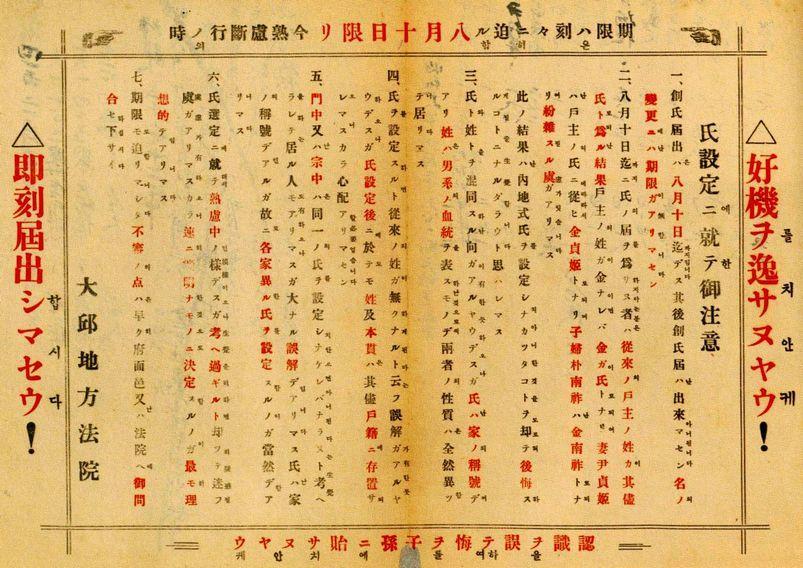

1940 handbill urging establishment of family name

Fiction as history

Yuasa Katsue (1946)

•

Yuasa Orokko (1944)

•

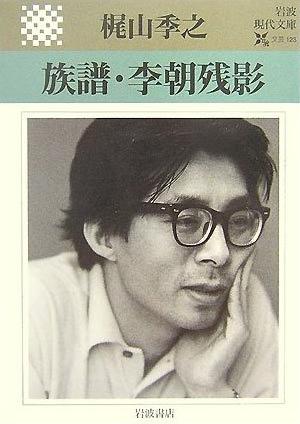

Kajiyama Toshiyuki (1963)

•

Richard Kim (1970)

•

Soh on Richard Kim (2008)

History as fiction

Robinson 2007

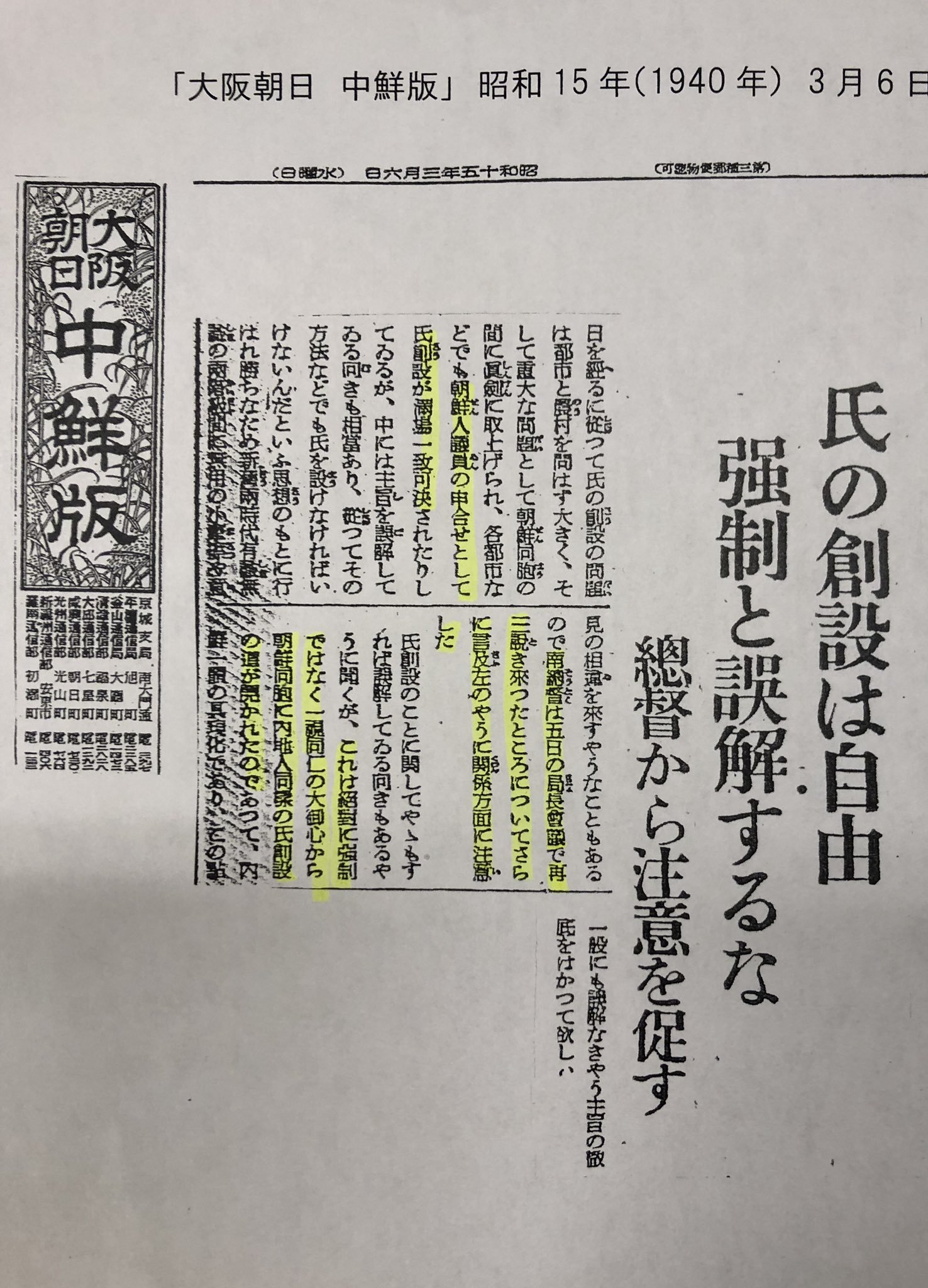

Click on article to enlarge Many images of this article -- and of other contemporary name-related reports in Japanese- and Chosenese-language newspapers -- have been clipped by researchers who have published them in books or posted them on blogs -- as Yamada did -- to present, as he says, "immoveable evidence" (ugokan shōko 動かぬ証拠) that many present-day accounts of the name-change ordinances and their enforcement are incorrect. This copy of the article is unique in that the poster, former House of Representatives member Yamada Hiroshi (山田宏 b1958), also showed the newspaper's masthead -- as he did with the name-related reports he clipped from the 3 August 1940 North Ch!sen edition (北鮮版) and the 16 August 1940 West Chōsen edition (西鮮版), among others. Yamada ticks many of the boxes that qualify him as a "rightist" and "revisionist" in the eyes of those who would critize his attempt to set the historical record straight. |

Overview

Name change policy by any name

Most people contend that Imperial Japan forced Chosenese to change their "Korean" names to "Japanese" names. The Government-General of Chosen mandated the adoption of a family name that everyone in a Chōsen household register would share, in accordance with Interior family law. Japanization of family or personal names was allowed, not required.

The 1939 name-change rules enforced from 1940 had two parts. The first part mandated the creation of a "family name" by designating an existing Chōsen-style clan name, or by adopting an Interior-style family name, as a family name. The second part was an entirely optional provision that had been part of Korean family law before Japan annexed Korea as Chōsen in 1910, for adopting a new personal name, which from 1940 (unlike earlier) could be an Interior-style name.

Some Chosenese wanted Japanized names, or the greater flexibility of Interior marriage and adoption laws. Most ignored the ordinances, and some, contrary to GGC policy, were pressured to Japanize their names. Many, however, maintained their Chōsen-style lineage names and openly used these names in both Chōsen and the prefectural Interior.

Newspaper reports

Numerous reports GGC's name decrees and ordinances and their enforcement were published in Japanese and Chosenese language newspapers. The larger, nationwide Interior newspapers published regional editions not only for regions within the Interior, for for regions within Chōsen and elsewhere outside the Interior.

The newspaper article to the right was published in the Wednesday, 6 March 1940 (Shōwa 15-3-6) issue of the "Central Chōsen edition" (Chūsen-ban 中鮮版) of Ōsaka Asahi (大阪朝日).

The main headline reads as follows (structural translation and [bracketed clarifications] mine).

氏の創設は自由 / 強制と誤解するな

Shi no sōsetsu wa jiyū / Kyōsei to gokai suru na

Establishment of family name free [choice of head-of-household] /

Don't misunderstand that [filing a notification

to establish a (new) name] is compulsory

Heads-of-households were obliged to choose a name to be used as the family name for all members of the household. They had two choices -- (1) not file a notification, which meant that the head-of-household's surname would become the family name -- or (2) file a notification, to declare (a) which surname in the household register would become the family name, or (b) declare a new name, even an Interior style name (previously forbidden), to be used as the family name.

The smaller subhead reads "Sōtoku ga chūi o unagasu" (総督が注意を促す) or "Government-General urges caution" -- meaning that heads-of-households should be wary of attempts force them adopt Interior style family names, and people generally should not believe rumors to the contrary.

All manner of evidence shows -- and all researchers who have done their homework have shown -- that not a few Chosenese adopted a Chōsen-style surname for use as a family name, whether by notification or default. Moreover, not adopting an Interior-style family name did not stop Chosenese from becoming police or military officers -- or even members of the Interior government's National Diet, since Chosenese males living in Interior election districts, who satisfied age and residence requirements, and paid taxes, could vote and run for public offices.

Note on nomenclature

In this article, as in all more recently written articles on Yosha Bunko websites, I have romanized 朝鮮 as "Chōsen" but used "Chosen" (or later "Tyosen") when citing contempary official English sources which refer the territory as such. People in Chōsen household registers were called 朝鮮人, which I romanize "Chōsenjin" except when citing official and other wources that have "Chosenese" (or later "Tyosenese").

"Japan" includes the Interior, Chōsen, Taiwan, and Karafuto. "Japanese" include Interiorites, Chosenese, Taiwanese, and Karafutoans.

These are the legal realities of history, and calling Chōsen and Chosenese "Korea" and "Koreans". Excluding them from "Japan" and "Japanese" make it impossible to understand contemporary and post-empire primary documents that objectively refer to them as such -- and, more importantly, distinguish "Chōsen" and "Chōsenjin" from say "Kankoku" (Korea) and "Kankokujin" (Koreans), which refer to at least two different things.

Here I will always cite and transliterate 朝鮮 and 朝鮮人 from Japanese texts as Chōsen and Chonenese. I will also use these terms when speaking in my own voice of 朝鮮 and 朝鮮人, but will write "Chosen" when used in received English texts, such as those published by the Government-General of Chosen. And of course I will faithfully cite texts that speak of "Korea" and "Koreans" but, when necessary, will bracket these terms with [Chōsen] or [Chosenese].

Setting the stage for name-change policy

In 1939 the Government-General of Chosen issued two GGC decrees and two related ordinances that concerned two entirely different "name" policies that would enter into force from 1940. The first was "create a family name" (sōshi 創氏) and the second was "change a personal name" (kaimei 改名).

The aims of these policies were complex but involved the following considerations.

- The name-change policies were not an end unto themselves. They were part of a more general objective of making Chōsen family law conform to the standards of Interior family law. This would facilitate compatibility in inter-territorial private matters, such as adoption and marriage between Chōsen and Interior families, in which the choices and effects of marriage and adoption in the two territories would be on a par.

- In matters of marriage and adoption, Interior law was far more liberal than Chōsen law. Some Chosenese were known to want an Interior-style law because it would liberate them from the traditional restrictions of Chōsen law. Liberalization of Chōsen standards, while giving households more freedom of choice, would not have prevented traditionalist households from observing the more restrictive standards.

- The name-change policies were not essential to the liberalization of marriage and adoption standards, but had more to do with "packaging" of the household system from the "bloodline" system of Chōsen (which mandated that individuals preserve their bloodline identities in lieu of a household identity) to the "non-bloodline" or "corporate family" system of the Interior (which mandated that individuals adopt the name of the family regardless of their bloodline).

- A number of Chosenese wanted the freedom to adopt Interior-style (Japanese-style, Yamato-style) names. Again, this freedom did not restrict the freedom of Chosenese to maintain Chōsen-style names. Reasons for coveting an Interior-style name were personal or familial. Some Chosenese saw the adoption of Interior-style names as symoblic of their assimilation. Their territorial status would not have changed, but they might feel that much closer to Interior neighbors if living in the Interior or fraternizing with Interior subjects in Chōsen, or if (as was also not uncommonly the case) they had Interior relatives through marraige or adoption. Outside Japan (i.e., outside the Interior, Chōsen, Taiwan, and Karafuto), such as in China or Manchoukuo, an Interior-style name might be socially more adventageous. In any event, such matters were "private" and the name-change policies merely facilitated choices not before available under Chōsen laws. In this regard, note that Interior law was also very restrictive on name choices, in that there were no provisions for adopting, say, a Chōsen-style name should one prefer such a name.

The "create a family name" (sōshi 創氏) policy required that heads of Chōsen households adopt a single "family name" (shi 氏) to serve as the family name of all members in the register. Conventionally, each member of a Chōsen household had the surname (sŏn 姓 J sei) they acquired through birth, and the surname was associated with a clan name, place of origin, or lineage name (pon'gwan 本貫), which identified the individual's patrilineal bloodline, and this would never change.

When adopting a family name, the head of household could choose any of the "surnames" in the register, such as his own, to serve as the uniform "family name". Or he could create an entirely new "Interior" or "Japanese" style family name. Or the head of household could do nothing, and by default his "surname" would automatically become the common "family name" for the household.

(1) The first part required the head of every Chōsen household to "create a family name" (sōshi 創氏). The head of household could do this by filing a notification declaring his own clan surname or the clan surname of someone else in the houehold, or adopting an Interior-stye ("Japanese") family name, as the common family name of everyone in the houshold register. If he did not declare a choice, then by default his own clan name would become the family name. No matter what name became the common family name, individual clan surnames would continue to be recorded in the register.

(2) The second part concerned "changing a personal name" (kaimei 改名). Individuals were free to adopt a new personal name if they wished. This was not a new procedure but one established before Japan's annexation of Korea as Chōsen in 1910. It had been, and would remain, entirely optional. And as before, it would require a petition for permission to change one's personal name and the payment of a nominal fee (the family name notification was free).

Unlike before these name-change rules, Chosenese would henceforth be able to adopt Interior-style ("Japanese-style") family names and/or personal names. There was no "compulsion" to "Japanize" names on the part of the Government-General of Chosen. There was some such compulsion on the part of people, including Chosenese, who coveted and favored the adoption of "Japanese" names. In the end only about 80 percent of Chosenese household heads adopted "Japanese" names. Chosenese clan names continued to be recorded in Chōsen household registers and could be used by households that wished to continue to observe traditional restrictions on marriage and adoption based on concerns about clan bloodlines. The family name could be any name the head of household chose, including his own Chosenese clan name. If no choice was declared, the head of household's clan name would automatically become the household's family name. have a single "family name" tChōsen family laws were revised to accommodate Interior (prefectural) family laws. Chōsen's family laws stressed clan bloodlines and households in which personal identities were based on clan bloodlines, and placed bloodline limitations on marriage and adoption. Interior family laws stressed a corporate rather than bloodline family standard and corporate family and corporate family rather than bloodline family standard, and permitted " clanPrefectural (Interior) Chōsen family law

1939-1940 "Soshi kaimei" policy in brief

The so-called "sōshi kaimei" (創氏改名) or "create family name, change personal name" policy sought to bring Chōsen family law into line with family law in the prefectural Interior of the Empire of Japan, by mandating the adoption of a common family name (氏 shi, uji) among members with different surnames in the same household register.

Individual surnames (姓) and their clan affiliations (本貫 본관 pon'gwan, or simply 本 본 pon) would continue to be recorded in accordance with Chōsen customs and could be used in private intercourse including marriage and adoption. Legally, however, all members of a household would share the same family name and be free to marry someone with the same family name or surname, while households would be free to adopt someone with the family name or surname -- subject only to other provisions of marriage and adoption laws.

The object was mainly to accommodate the "corporate family" standard of the Interior Civil Code, most of which had by then been applied to Chōsen, and to give individuals and families more flexibility when it came to marriage and adoption. The adoption of Interior standards of family law also facilitated private matters -- such as marriage and adoption -- between Interior and Chōsen individuals and households. In otherwords, the determination of applicable territorial laws would be easier if the territories shared a similar standard.

Many Chosenese considered Interior family law standards to be incestuous, and were upset by the notion that only personal names would legally differentiate members of the same household. Some Chosenese, however, welcomed the flexibility.

The change in Chōsen family law was also intended to facilitate assimilation, should Chosenese households or individuals wish to adopt Interior-style family and personal names -- Suzuki rather than Kim, or Tarō rather than Chŏgi, say. Some Chosenese wanted to formally adopt Interior style names to facilitate their personal goals, while others thought the very idea of abandoning their native Chōsen names a betrayal of their racioethnic identity.

Family names

The head of each Chōsen household register was required to declare a common "family name" or passively accept that, by default, his surname would be taken to be the family name. He -- the head of household usually was usually a male -- could declare any surname in the present register to be the family name -- Kim, Nam, Yi, whatever. Or, he could adopt a new family name, like Watanabe or Yamada, by a certain date. Should he fail to file a notification by this date, his surname -- Kim, say -- would be taken as the family name to be legally shared by everyone in his register.

Family names and their clan affiliations were continue to be recorded for each member in household. Members of the household could continue to invest whatever meanings they wished to such names in private social intercourse, but the restrictions on marriage and adoption that such names had imposed on private actions like marriage and adoption would have no longer be sanctioned by even customary law.

Personal names

While households were required to create a single family name to replace the multiple surnames in a register, individuals were free to continue to use their personal names as they were. Whereas family-name creation was mandatory and free, personal-name change required application and payment of a nominal fee.

After filing an application, one had to wait for a grant of permission from a court -- as was the practice in the Interior under the Family Register Law -- as is the practice in Japan today.

The Interiorization of Chosen

A decree issued by the Government-General of Chosen in 1939 mandated the establishment of family names on Chōsen household registers by 10 August 1940. The family name policy was part of a more general movement to introduce Interior (prefectural) family, family registration, and civil law to Chōsen, which had been part of Japan's sovereign territory since 1910.

The introduction and enforcement of the name-change decree makes sense only as a means to facilitate the legal integration of Chōsen into the Interior, or prefectural, subnation. And changing names makes sense only in terms of how Japan had used family registers to nationalize its own prefectures and territories which became prefectures or parts of prefectures.

Chosen household registers

Japan nationalized all territories that became part of its sovereign dominion through household registration. By "all" I mean literally all -- the prefectures, then territories like Ezo (Hokkaido) and Ryukyu (Okinawa) which became prefectures, islands grounps like Chishima and Ogasawara, which became affiliated with prefectures, treaty-ceded territories like Taiwan and Karafuto, and finally the treaty-annexed territory of Chōsen.

Not only were the populations of non-prefectural territories nationalized through household registration, but as the territories became legally assimilated through decress based on prefectural laws, the more their populations were subjected to prefectural-style family law -- including the Family Registration Law and related articles of the Civil Code.

1909 People's Register Law

Japan was involved in the improvement of household registration in Korea before it was annexed as Chōsen. It was mainly through Japanese urging and guidance that the Empire of Korea adopted its first comprehensive household registation law (民籍法 민적법 Minjŏkpŏp J. Minsekihō) in 1909 (see Affiliation and status in Korea: 1909 People's Register Law and enforcement regulations for details).

In 1909, a year before formal annexation, and based on fresh Japanese studies of Korean family customs and registration practices, the Resident-General of Korea directed the barely sovereign Korean government to enact the People's Register Law. This law, one of the last laws of the short-lived Korean Empire, was based on Korean customary law, and was intended to make family registration more efficient and controllable.

Resident-General of Korea The People's Register Law was promulgated by the Emperor of the Empire of Korea (大韓帝國 대한제국 Tae-Han cheguk J. Dai-Kan teikoku), which was founded in 1894. In 1905, when Korea become a protectorate of Japan, Japan established the Residency-General of Korea or "Office of the Resident-General of Korea" ((韓国統監府 Kankoku tōkan fu) in Seoul. This became the Government-General of Chosen or "Office of the Governor-General of Chosen" (朝鮮総督府 Chōsen sōtoku fu) in 1910, when Japan annexed the Empire of Korea and changed its name to Chōsen.

Post-annexation registration decrees

In 1912, after Korea had become Chōsen, a part of Japan's sovereign empire, the governor-general proclaimed the Chōsen Civil Matters Ordinance (朝鮮民事令 Chōsen minji rei, Meiji 45 Ordinance No. 7). This ordinance was mostly an effort to codify customary Korean civil law, including family law.

The Interior revised its Family Registration Law in 1914, and the People's Register Law was partly revised in 1915 to incorporate some features of the new Interior law. The Civil Matters Ordinance was heavily revised in 1922. The revisions, which came into effect the following year, included a section on family registration, and this occasioned a Family Registration Decree (朝鮮戸籍令 Chōsen koseki rei) which made Chōsen registers more like those in the Interior.

Naichijin and other status distinctions

The new civil and family registration decrees differentiated "Interior persons" (内地人 Naichijin) as those with Japanese nationality whose principal register (本籍 honseki) was in the Interior (内地 Naichi) -- in a prefecture. The revisions enabled changes in the registers of the four subnations because of marriage, adoption, or recognition.

Some sources (which I have not yet confirmed) state that the new registration rules also provided for recording two former outcaste statuses -- paekchŏng (白丁 백정 J. hakucho), who engaged in leatherwork or other occupation regarded as unclean -- and tohan (屠漢 도한 J. tokan), literally "men who slaughtered" or butchers. Both statuses had been abolished in 1894 toward the end of the Yi Dynasty. I would guess that the object of resurrecting them in registers was to help police suppress proletearian movements in Chōsen like those of the Suiheisha (Levelers Association) and other "buraku liberation" organizations in Japan.

Accommodating inter-subnational marriages

The register regulations were revised to accommodate a 1921 provision (Article 3) in the 1918 Common Law, which made it possible for Chōsen subjects to marry Interior and other Japanese subjects. Article 3 meant that status actions involving the registers of two territories (subnations) would be treated the same as status actions between two Interior registers -- except that movements between the registers of two subnations would effect a change in subnationality -- just as international marriages and adoptions at the time usually involved a change in nationality.

In other words, a Chōsen woman (a Japanese woman of Chōsen subnationality) who married an Interior man (a Japanese man of Interior subnationality) -- or a Chōsen subject adopted into the household of an Interior subject -- would become an Interior subject. Similarly, an Interior woman who married a Chōsen subject, or an Interior subject adopted into a Chōsen household, would become a Chōsen subject.

Chosen governors-general

In 1939, when a number of name-change decrees and ordinances were issued in Chōsen, The Government-General of Chosen (Chōsen sotoku fu 朝鮮総督府) was formally overseen by the "Land Development Ministry" (拓務省 Takumusho), which was variously called "Ministry of Overseas Affairs" and "Colonial Department" in English. This ministry also oversaw the Taiwan Government-General and the Karafuto Government.

The powers of the ministry over the governors-general of Taiwan and Chōsen, however, were limited. The governors-general were appointed directly by the Emperor and held ranks which, in terms of protocol, make them equivalent to a Imperial Cabinet minister or premier. The Governor-General of Chosen (Chōsen sotoku 朝鮮総督) in particular had practically unlmited authority over the territory.

All seven of the governors-general of Taiwan who served from 1895-1919 were military officers of admiral or general rank. Of the twelve who served from 1919-1945, all but the last three were civilians. Most served compartively short terms, were not politically prominent, and hence were subject to closer control by the Imperial Cabinet.

In sharp contrast, all ten of Chōsen's governors-general were higher ranking military officers of political prominence. Practically all had been, or became, an Imperial Cabinet minister. Four of the six who served after the 1 March 1919 movement had been, or became, prime ministers.

Source For the above analysis of Taiwan's and Chōsen's governors general, I am particularly indebted to I-te Chen's doctoral dissertation, Japanese Colonialism in Korea and Formosa: A Comparison of its effects upon the development of nationalism, Political Science, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, University of Pennsylvania, 1968, pages 92-98.

The last three governors-general of Chosen

General Minami Jirō (南次郎 1874-1955), Chōsen's governor-general from 1936-1942, had commanded the Japanese military in Chōsen from 1929-1930 before serving as Minister of the Army in 1931. General Koiso Kuniaki (小磯国昭 1880-1950), who had commanded Japanese troops in Chōsen during Minami's term as governor-general, replaced him as governor-general from 1942-1944, then went on to be the prime minister of Japan from 1944-1945. General Abe Nobuyuki (阿部信行 (1875-1953), who replaced Koiso as governor-general from 1944-1945, had been the prime minister from 1939-1940.

Minami and Koiso were tried, convicted, and sentenced to life imprisonment as Class-A war criminals. Koiso died in Sugamo prison. Minami was released a year before his death for reasons of poor health. Abe was purged from public office, and arrested but later released without charges.

The legal authority of governors-general

There was some debate about how to govern Chōsen. Japan's lawmakers had disagreed over whether the Constitution, and laws passed by the Imperial Diet for the prefectures, could apply to new territories.

Those who argued that Chōsen required independent overseeing until it was ready for legal integration prevailed. Consequently, Chōsen was governed by decree legislation rather than through the Imperial Diet.

Legal authority took many forms. The three most important in Chōsen were as follows.

Laws (法律 hōritsu) Laws were enacted by the Imperial Diet, as provided by the Meiji Consitution. Laws passed by the Diet were effective only in prefectures unless, at time of their enactment, they included provisions that specifically extended them, in part or in whole, to one or another non-prefectural territory within Japan's sovereign domain. The Diet could also extend parts of all of a prefectural law to a territory.

Decrees (制令 seirei) Decrees proclaimed by a governor-general in Chōsen were equivalent to laws in the Interior. They required sanction by the emperor before promulgation, but in emergencies the governor-general had the authority to promulgate a decree before obtaining imperial sanction.

Ordinances (府令 furei) Ordinances -- or more fully Government-General ordinances (朝鮮総督府令 Chōsen-sōtoku furei) did not require imperial sanction. They were issued and enforced entirely under the executive authority of the Governor-General. They usually concerned minor issues, including issues related to the enforcement of ordinances.

Undercurrents of legal integration

While Chōsen's governors-general were inclined to rule the territory as they saw fit, there movements to centralize power in Tokyo. Already at war in 1939, the Japanese government was looking for ways to consolidate its ministries and bring its sovereign empire -- consisting of four subnations, each then under its own legal system -- beneath a common legal umbrella.

This meant integration, which meant embracing the Taiwan, Karafuto, and Chōsen in the legal arms of the prefectural Interior subnation. They would then under interiorization (内地化 naichika) and eventually achieve prefecturehood. First, though, they would have to be put under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Interior Affairs.

Interior Ministry placed in charge of Taiwan, Karafuto, and Chosen

In 1942, the Land Development Ministry, which had overseen both all territories outside the prefectures, was disbanded and the Greater East Asia Ministry (大東亜省 Dai-To-A Sho) was created. The new ministry took over supervision of the territories that were not part of Japan's sovereign empire. Taiwan, Karafuto, and Chōsen were brought under the "Home Affairs Ministry" (内務省 Naimusho), which is better understood as the Interior Affairs Ministry.

Karafuto, long groomed as a de facto Interior entity, was legally incorporated into the Interior in 1943. How long it would have taken to fully assimilate Taiwan and Chōsen into the prefectural system is speculative, given the turn of events and inevitable defeat. However, bringing Taiwan and Chōsen under the Home Affairs Ministry meant that they, too, were bound to fully integrated into the prefectural system.

See Legal integration with Interior for an account of the interiorization of Karafuto preluding Taiwan and Chōsen.

Would Taiwan and Chōsen, too, eventually have become prefectures? Probably.

An ordinance that would have made their governors-general as accountable to the Imperial Cabinet and Diet as prefectural governors was never fully implemented. More legal restructuring was needed to bring Taiwan and Chōsen under Interior laws so that they could be administrated as prefectures. But the wheels of total legal integration were in motion. Had Japan won the war and contained Chosenese resistance to its domination of the peninsula, Taiwan and Chōsen would eventually have become integral parts of the prefectural Interior, as had Karafuto -- just as, later, Alaska and Hawaii gained statehood in the United States.

This does not mean that Chōsen and Taiwan, given their geographical size and complexity, would have been prefectures -- but merely that they would have been administered along with the prefectures under common civil and penal codes, among other such general laws. They would have retained their regional names, and in the manner of prefectures had a certain degree of local autonomy in the governance of local matters. Election districts would have been established, with suffrage rules similar to those for Interior districts. There would have been local assemblies and representation in the Imperial Diet. Presumably, also, there would have been more opportunity for changes of status both within and between family register systems.

Racioethnic assimilation

Racial assimilation policies were also in full swing by the end of the war. Racial assimilation meant, basically, the Yamatoization of language, names, and all manner of customs, including religious practices. Let's look very briefly at what happened in Chōsen in terms of family registration, since that is what leads to the problems of some Koreans in Japan today.

By the late 1930s, the Governor-General of Chosen had issued all manner of ordinances and decrees intended to Yamatoize the thought and behavior of Chōsen subjects. In 1937, Japan had taken advantage of clashes in China to start what had developed into a new Sino-Japanese War. Legal integration and racial assimilation were being accelerated not only in Chōsen but throughout the sovereign empire, including the Interior, in anticipation of having to mobilize all subjects for military service and labor. Interior ordinances, too, made it easier for Chōsen subjects to settle in the prefectures, to facilitate the need for labor.

Then in 1939, the third revision of the Civil Matters Ordinance included certain provisions concerning names in family registers. The name-change provisions are commonly dubbed "Create family name and change personal name" [Soshi kaimei]. They were not, however, standalone provisions but part of the general revisions. The revisions were enforced from 11 February 1940 and Chōsen subjects were given six months to comply with the name-change provisions.

The most significant name provision concerned the creation of a "family name" [shi]. Japanese families were corporate. They were not based on lineage per se. Everyone in a family, including those who married or were adopted in, assumed the same family name. There was no keeping track of ancestral lineage other than to record the previous family name of someone who had entered a register through marriage or adoption. Cousins could marry, though few actually did. People totally unrelated by blood could be adopted into the family for the purpose of carrying on the family name.

Chosenese did not have initially have family names. They had surnames which were passed down from father to child and never changed. They represented an individuals patrilineal descent from an ancestral progenitor. They were, in essence, a clan name, and no one from the same clan could marry. Any Kim could marry any Pak, and a Kim of the X Kims could marry a Kim of the Y Kims, but not another Kim of the X Kims. If there was no male heir, then an second or third son of another family from the same clan would be adopted. Women kept their surnames after marriage, so the married women in an extended family might all have different surnames. And registers kept track of the individual surnames and clan names.

The object of the provision to create a family name was to facilitate total legal integration of Chōsen into the Interior polity. It was also, of course, to hasten the adoption of Yamato-style names, which in fact some Chosenese had already begun doing. It was not simply a matter of every Chosenese being opposed to the changes that were being imposed by Japanese rule.

Nor was it a matter of obliterating Chōsen family customs as such. Though Chosenese would be appear to have a Interior-style family structure, their surnames and clan names would still be recorded. Chosenese who wanted to continue to follow the strictly sanguilineal patriarchal traditions were perfectly free to do so. In the meantime, the Interior-style laws enabled certain reform-minded Chosenese to marry or adopt whomever they wanted. In any case, the governor-general's mission was to ease, tease, nudge, and otherwise pressure Chosenese into an Interior frame of mind about everything -- including the ever-important family registers, which epitomized the empire's priority on bureaucratic conformity and order.

Timing of name-change decrees

The enforcement date marked the 2600th anniversary of the founding of Yamato by Jinmu, its first emperor, according to accounts of the genesis of the country in the Nihon shoki (日本書紀 720).

Significance of 1940

11 February 1940 was the first day of the year 2600 on the Yamato calendar. It marked the Genesis of the Realm [Kigensetsu], when Jinmu is supposed to have started the putatively unbroken succession of the priestly heads of the imperial household. This date is now called National Founding Day [Kenkoku kinenbi], and it continues to be the most important national holiday for true Yamatoists.

1940 was also the year Japan was to have hosted the Olympics. After Japan invaded China, the International Olympics Committee canceled Tokyo as the site of the games, and the war in Europe prevented the 1940 games from being held anywhere. Five years later, the empire itself had been canceled, and with it the dream of integration and assimilation.

Register development after annexation

After the annexation treaty came into effect, and Korea became Chōsen, Japan went about nationalizing Chōsen's population registers, as it had the registers of all territories it had incorporated into its sovereign empire -- from Ezo (Hokkaidō) and Ryūkyū (Okinawa), to Formosa (Taiwan) and Karafuto. Not only did Korea's household register laws continue to be used as Chōsen laws, but they were revised in 1915 to require heads of households to make notifications of changes in registration matters.

In 1922, the 1912 Chōsen Civil Matters Ordinance (朝鮮民事令 Chōsen minji rei), which had extended parts of the prefectural Civil Code to Chōsen, was revised. The Chōsen Family Register Ordinance (朝鮮戸籍令 Chōsen koseki rei), which introduced many elements of prefectural family register practices, was also promulgated (Governor-General Ordinance No. 154) that year.

Pon'gwan names retained

By 1923, Chōsen family registers had come to be almost the same as prefectural registers. One major difference was that Chōsen registers continued to have a box for the ever important 本貫 (본관 pon'gwan J. honkan) -- the ancestral clan or lineage name of each member of a household. As on prefectural registers, Chōsen registers also bore the 氏名 (씨명 ssimyŏng J. shimei) or "family name and personal name" of each member.

The lineage name is generally the name of the locality from where the clan is supposed to have originated in antiquity. The practice of keeping track of such names continues among some Chinese. The practice, though adopted from China through Korea by some people in early Japan, did not take root in Japan, where there has been much less concern about marriage between close relatives.

Under traditional Korean family law, and under ROK law until very recently, a man and woman with the same family name (e.g., Kim) could not marry unless they were from different Kim clans -- i.e., unless their lineage name was different. Korean wives would join their husband's household register after marriage, but not adopt his family name. And no one's lineage name would change. Children would usually take their father's family name -- and its lineage name.

Name-change policies

Forthcoming.

Intentions of name-change policy

The name-change policy had two objectives: (1) impose a single family name on all household registers, and (2) permit changes in personal names.

Impose a single family name on all households

The principle object of the name-change policy was to force Chōsen subjects within the same household register to use only one name as their legal family name. Their surnames and surname origins would continue to be recorded in the register, and people would be free to use them in private affairs, including marriage.

The policy itself did not force any head of household to adopt an Interior style family name. Heads of household were free to simply wait until the 6-month compliance period ran out -- in which case their own surname would be taken as the family name of the register, hence of all its members -- with no change in their surnames.

That in the end many household heads did create an Interior-style family name for their register means only that they submitted to extralegal pressure to do so -- or they accepted the argument, ardently made by family-name advocates, that adopting a distinct name unlike any surname in the register would create less confusion among people who wanted, in their private life, to continue to make the customary surname distinctions.

Permit changes of personal name

There seems to have been no real interest in forcing Interior-style personal names on Chōsen subjects. Not only were such changes entirely voluntary, but they required application to a court and payment of a fee -- just as they did then in the prefectures, and just as they still do in Japan today.

How name-change policy operated

Family names were easily created and cost nothing -- except, for some, a chunk of racioethnic pride. Personal names cost 50 sen, and arguably no lost pride since they were strictly voluntary.

Surname becomes family name by default

If a head of household did nothing within the six-month compliance period, by default his own surname would become the family name of his register. Everyone in the register, regardless of their surname, would assume this single family name.

If the head of household's surname was Nam, and his wife's surname was Hwangbo, and his first son's wife's surname was Sama, and his third son's wife's surname was Pak -- all would assume the name Kim as their legal family name -- while continuing to be Kim, Hwangbo, Sama, and Pak in their private life.

Creation of family name

Heads of households who did not wish their own surname to be the family name of the register -- for whatever reason -- had to file a notification of creation of family name with the local registrar. "Creation" meant exactly that -- adopting a name that was not already a surname in the register -- and, to complicate matters, a name that qualified as an "Interior-style" family name.

A head of household named Kim, who wished to incorporate his surname in the family name, was expected to adopt a name like Kaneda or Kanemoto. However, Kim could also adopt a name like Yamada or Tokuyama.

If Kim did not wish to embed his surname in a Yamatoized family name, he could create an entirely new "Interior-style" name -- meaning one that did not exist anywhere -- drawing from the numerous morphemic elements of the Japanese language that have enabled the huge variety of family names in Japan. The new name did not have to be an unambiguously Yamato name, and in fact many of the adopted names were easily recognizable as Korean hybrids.

Resistance to name-changing

The family-name provided that, if a head of household hadn't filed a choice by the end of the period, his surname would, by default, become the family name for every man, woman, and child in his household register. Hence all Chōsen subjects now had family names, whether or not they had been fully or quasi Yamatoized. And everyone was expected to use their family names in all official intercourse.

The "change personal name" part of the provision was entirely optional. One could not just declare a choice of a new personal name by filing a form. A decree by the governor-general even clarified that name-change applications had to be approved by his office. The application procedure even involved a small fee, as do petitions to family courts today. In any event, only about ten (10) percent of all Chōsen subjects went to the trouble to change their personal names.

Moreover, there was really nothing new about the "change personal name" provision -- as it facilitated a customary choice which had been codified in Korean family law as early as 1909 (see Affiliation and status in Korea: 1909 People's Register Law and enforcement regulations for further details).

Some family names, and even personal names, could be read in Yamato without having to be changed. And not a few Chosenese had given their children personal names that could be taken as Yamato names if someone cared to see them that way. Practically all of the people who had been born and raised since 1910 spoke Yamato. Nearly thirty years had passed since the annexation. All Ainu, and most other non-Yamato people in the sovereign empire, had long since been pressured into adopted Yamato names, through the same process of family registration under Interior laws. As we shall see later, this is essentially what continues to happen when aliens naturalize in Japan today.

To be continued.

Compliance with name-change policy

By the middle of the six month period, not many heads of household had declared a choice of family name. Apparently officials and others began putting pressure on more people to file, for by the 10 August 1940 deadline about eighty percent of the households had complied.

The governor-general is said to have issued three orders to stop the coercion. Apparently most of the pressure to comply came from pro-Japan Chosenese.

None of this excuses the essentially coercive of the name-change policy to begin with. Imposing a single surname on a household of people accustomed to going by different surnames is in itself coercive. Forcing them to adopt a single family name of an essentially alien style is destruction of both personal and family identity.

Kim So-un aka Tetsu Jinpei

The poet Kim Soun (金素雲)

Kim has greatly inspired his granddaughter, the singer/song-writer Sawa Tomoe (b1971). In 1998, Sawa became the first Japanese singer to be permitted to perform a concert in the Republic of Korea, which until then had been closed to Japanese language media and popular culture.

To be continued.

Legacy of naivete

Forthcoming.

For many poignant anecdotes of Chosenese reactions to the deprivation of their ethnic names, see Richard Kim, Lost names: Scenes From a Korean Boyhood (New York: Praeger, 1970); and Kim Il Myŏn, "Chōsenjin no 'Nihonmei': Nihon tōchika no Nihonmei shiyō no yūrai to 'Sōshi kaimei"' [The "Japan names" of Chosenese: The origin of the use of Japan names under Japan's rule and "Sōshi kaimei"], Tenbō, No. 208 (April 1976): 34-54.

Kim's article gives an account of Korean poet Kim So Un (金素雲 1907-1981, who responded to the Sōshi kaimei [Create family name, change personal name] order by adopting the name Tetsu Jinpei. He intended the name to mean something like "I don't give a damn that I've lost my gold!" The Chinese character for Tetsu [iron] consists of two parts which mean "gold lost" -- i.e., iron is metal without gold -- alluding to the fact that Kim had lost his ethnic name Kim [gold].

On Korean time

Chōsen subjects who adopted Interior-style names, for whatever reason, had only five years to get used to their new names. On 15 August 1945, they were suddenly "liberated" of Japanese rule. "Chōsen" was supposed to become "Korea" again. But as of this writing -- over 60 years later -- it has yet to return to statehood.

Something happened on Chōsen's way back to being Korea. The territory was divided at the 38th parallel, and it took three years for the southern and northern sectors to become the Republic of Korea and the Democratic People's Republic of Korea.

"Chosenese" who remained in the prefectures did not immediately become "Koreans" either except in English documents issued by the Allied Powers and Occupation Authorities. They had to wait for the emergence of the new political entities on the peninsula, and for the formal settlements between these entities and Japan. In the meantime, their legal status in Japan remained in limbo.

Japan and ROK settled in 1965. Japan and DPRK have yet to settle, and ROK and DPRK remain divided.

The San Francisco Peace Treaty left Chosenese without Japanese nationality. Most Chosenese in Japan have became ROK nationals. A few have become nationals of countries other than ROK or DPRK. The rest remain Chosenese in Japan's eyes, including those who have become nationals of DPRK in the eyes of DPRK, PRC, and other states that recognize DPRK.

To be continued.

While many people throughout the empire must have sensed that the war was coming to an end, the abruptness and manner of its ending must have caught most off guard. Long before the end of the war, governments throughout the empire had begun making plans for all manner of administrative and demobilization contingencies, but none was prepared for the problems they faced by Hirohito's announcement that Japan had unconditionally surrendered and agreed to abandon its territories, including Taiwan, Karafuto, and Chōsen.

The Government-General of Chosen, like the Residency-General of Korea before it, had always relied on the participation of many Chōsen subjects. Though its higher posts were dominated by Interior subjects, the closer its offices came into contact with the people, the more likely they were staffed if not also led by Chosenese.

The Government-General of Chosen planned for a number of contingencies, including the orderly transfer of all its powers to Chosenese. Such plans obviously had to involve the Chosenese who would step into the posts held by Interior subjects. These plans were disrupted by the sudden end of the war and the equally sudden division of Chōsen into two military occupation zones under the control of two foreign states.

The military line drawn at the 38th parallel by the United States and the Soviet Union was contrived as a way to divide the labor of accepting Japan's surrender, receiving control of the Government-General of Chosen and its properties, and carrying out demobilization and repatriation. The US and USSR had discussed the possiblity of a multilateral trusteeship over the entire peninsula, but this idea never materialized.

Throughout the period of Japanese rule, there were many Korean independence movements, each with its own designs on the country's reigns. When the moment came to take them back, Koreans in both occupation zones found themselves faced with new occupiers who had their own agendas.

Koreans in the southern zone had to contend with the United States Army Military Government in Korea. USAMGIK was under SCAP in Japan, which in some sense meant that the southern zone of Korea was still being linked with Japan. Not until the summer of 1946 did USAMGIK became an independent command directly teathered to the US government in Washington, D.C.

USAMGIK preferred to work more closely with Japanese authorities -- namely, the Government-General of Chosen -- than with the provisional government of Syngman Rhee, which claimed the right to rule. Several Korean independence factions ended up fighting each other while the United States worked embraced Japanese and Koreans who had worked closely with Japanese to effect a smooth transition of authority and deal with the repatriation of over a million people both ways, from Korea to Japan and from Japan to Korea.

USAMGIK began to systematically replace Japanese with Koreans in Government-General of Chosen posts, beginning with the higher posts. Most, but not all Japanese, had been replaced in government posts by the spring of 1946.

The United States, failing attempts to negotiate with USSR a reunification of the peninsula, agreed to allow Syngman Rhee's provisional government to establish the Republic of Korea. The United Nations sanctioned the founding of ROK on 15 August 1948 and recognized it as a state on 12 December. The UN did not recognize the Democratic People's Republic of Korea, which the USSR had allowed to be founded on 9 September.

ROK inherits Government-General

Shortly after its founding, USAMGIK transferred to ROK all of the properties which USAMGIK had taken over from the Government-General of Chosen and other Japanese entities. When replacing USAMGIK, ROK also inherited all that was left of the Government-General of Chosen -- meaning most of its civil offices and legal system, and even a few Japanese who USAMGIK had left in old posts or installed in new ones.

Shortly after its occupation of the southern zone of Korea began, USAMGIK quickly abrogated Government-General of Chosen decrees and ordinances which had limited freedoms of speech and religion, or engendered discrimination because of "race, nationality, faith, or political thoughT" (but not gender). However, decrees and ordinances that facilitated essential administrative functions -- including the population registration system -- were allowed to remain in force. (Kim Yŏngdal 2002: 99, 141)

1946 order concerning restoration of Korean names

On 23 October 1946, USAMGIK issued a law, which was immediately effective, called "Chōsen surname and personal name restoration ordinance" (朝鮮姓名復舊[旧]令 조선 성명 복구령 Chosŏn sŏngmyŏng pok'ku ryŏng J. Chōsen seimei fukkyū rei). Article 1 of the law, Order No. 122, stated that its purpose was to make it easy to restore Japanese-style names to Korean-style names. (Kim 2002: 142)

Article 2 nullified Japanese-style family names retroactive to their day of establishment. However, it gave those who wished to keep such names sixteen days within which to notify the registrar of their intent. Otherwise, the registrar would restore all surnames in the registers. (Kim 2002: 142-143)

Article 3 gave those who had changed their Korean-style personal names to Japanese-style personal names six months within which to notify the registrar of their wishes. After this period, they would have to submit a name-change petition to a court with jurisdiction -- the standard procedure for changing names. (Kim 2002: 143)

Article 4 nullified all laws inconsistent with the order, from their day of origin -- referring to all Government-General of Chosen decrees and ordinances concerning adoption of Japanese-style names. (Kim 2002: 143)

In other words, USAMGIK accepted the legal infrastructure built by the Government-General of Chosen, during its thirty-five years of rule, as something to be selectively reconstructed in a legal manner. On 1 November, USAMGIK issued detailed procedural provisions concerning name restoration, which Koreanized terminology in standing laws related to household registration. Hence 氏名 became 姓名, and 姓及本 or 姓及本貫 became simply 本 or 本貫 (Ibid. 144).

In the USSR-controlled north, Japanese institutions were shown no patience. The north more aggressively dismantled Japan's legal infrastructure. Ordinances nullified any articles of law which went against the grain of Korean sentiments. Corrective measures were taken to reverse all Japanizations of household registers. Adoptions of husbands, and adoptions of heirs with different surnames, were also nullified earlier than in the south. (Kim 2002: 99-100, 145-149).

1949 nullification of husband adoption in ROK

In 1949, a year after ROK declared itself a state, its Supreme Court (大法院 대법원 Taebŏbwon) retroactively nullified an instance of husband adoption (婿養子 J. muko yōshi) for the reason that such a practice "is contrary to public order and good morals" (Kojima Takeshi, Han Sangbŏm, and Yun Ryongt'aek, 1993).

1999 abrogation of of same-clan marriage restriction

Fifty years later, In 1999, a year after it degenderized its nationality, ROK finally liberalized its marriage law to permit unions between people who had same-clan surnames.

1939 name-change decrees and ordinances

In 1939, the Governor-General issued an order promoting the adoption of a "family name" in addition to the usual "surname" and "clan name" most Chosenese had. The order also permitted Chosenese to change their personal names. People were given until 1940 to adopt a family name but could change their personal name anytime.

To be continued.

The Government-General of Chosen issues three short decrees related to sōshi kaimei. The texts of all three decrees are presented and translated here.

The creation of a family name was a family matter because the name chosen would apply to everyone in the same household register -- as in the prefectures. Family law in the prefectures required that everyone in the same register go by the same family name. There were no surnames and no clan names.

Chosense were generally not permitted to adopt prefectural style family names. Hence the continuation of customary Chosenese name practices in Chō registers under Japanese control -- until the 1939 decrees concerning the creation of family names and changing of personal names -- when suddenly people were being encouraged to adopt prefectural naming conventions.

Though Chosenese in the same household register were required to adopt a single name for use as their family name -- to comply with the prefecturalized registration rules -- the registers continued to provide boxes for the pon'gwan (本貫) place of origin or lineage name. In other words, Chosenese were not prohibited from keeping track of lineage names, or from using such names in determining who could marry whom.

In 1944, a bill was introduced which would have permitted Chōsen and Taiwan subjects to move to prefectural registers under certain conditions. It was not, however, enacted, apparently out of fear that it would give rise to problems between Interior people and migrants from Chōsen and Taiwan (my translation).

内鮮人及内台人間ニ重大ナル混淆紛乱ヲ生ジ指導取締上種々困難ナル問題ヲ生ズベシ

This will engender serious mixing and confusion between Interior and Chōsen people and Interior and Taiwan people, and engender various difficult problems in terms of guidance and control.

To be continued.

Miyata Setsuko, Kim Yŏngdal,

Miyata Setsuko, Kim Yŏngdal,and Yang T'aeho Sōshi kaimei [Create (family) name, change (personal) name] Tokyo: Akashi Shoten, 1992 From Miyata's epilogue "It's generally said that Japan did the terrible thing of forcibly making [Chosenese] change their names. However, the object [of the "create a family name, change personal name" policy] was was clearly to "create a family name", that is, "establish a corporate family". This "establish a corporate family" sense was difficult to obtain in comparison with the "change (personal) name" phenomenon that [more] directly struck people's eyes" (page 261) |

Mizuno Naoki

Mizuno NaokiSōshi kaimei: Nihon no Chōsen shihai no naka de [Sōshi kaimei: In the midst of Japan's Chōsen control] Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 2008 From Mizuno's introduction "In the information and views [about sōshi kaimei] that can be obtained through books, magazines, and the Internet . . . there are many errors" (page i) |

Sources

Soshi kaimei sources are extremely abundant. Most presentations on the Internet and in books represent degraded versions of the original ordinances and decrees. I have tried to represent the original texts as closely as I can determine them to have been.

The texts of most of the relevant ordinances and decrees related to Chōsen are reproduced in the back of the 1992 study by Miyata, Kim, and Yong. The texts of most of the Meiji proclamations can be found at the National Diet Library Digital Archive Portal [Kokuritsu Kokkai Toshokan Jijitaru Aakaibu Pootaru (NDL DAP)] (retrieved December 2006). Versions of several of the laws of interest can be found at 中野文庫法令集 (Nakano Bunko / "The Nakano Library")

Different versions different transcription conventions. There is considerable variation in marking of sentence and paragraph greaks and in showing voicing of katakana. In general I have followed Miyata et al 1992 in matters of the text itself. In adapting its vertical presentation to the horizonal one of this webpage, I have numbered articles and paragraphs with Arabic rather than Sino-Japanese numbers.

The texts of older laws today are usually reproduced with simplified Sino-Japanese characters. I have shown traditional characters only when citing a source that uses them. However, other features of older texts have been preserved -- including the absence or sparcity of puncutation, the use of katakana rather than hiragana, older kana orthography, and a tendency not to show voicing.

Works cited

I have very liberally used the following sources, all of which are reviewed under "Names" in the "Population registers" section of the "Bibliography" feature of this website. See also the biographical note on the naturalization and untimely death of Kim Yŏngdal, whose legal name was Ōno Eitatsu.

Miyata Setsuko, Kim Yŏngdal, and Yang T'aeho 1992

Kim Yŏngdal 1997

Kim Yŏngdal 2002

Tsuboi et al 2003

Mizuno Naoki 2008

Nakayama Nariaki 2013

Another interesting source, which compares the very different approaches taken in Taiwan and Chōsen regarding opportunities to adopt Japan-esque names, is the section on "The Name-Changing Campaign" in the following article (pages 55-61).

Wan-yao Chou

The Kōminka Movement in Taiwan and Korea: Comparisons and Interpretations

In Peter Duus, Ramon H. Myers, and Mark R. Peattie (editors)

The Japanese Wartime Empire, 1931-1945

Princeton (NJ): Princeton University Press, 1996

Pages 40-68 (Chapter 2)

There are a number of problems in Chou's comparisons of "name changing" in Taiwan and Korea (Chōsen), with regard both to particulars and generalities. I will comment here only on generalities.

Chou concludes that the differences in name-change policies in Taiwan and Korea "substantiate the commonly held view that Japanese rule in Korea was harsher, whereas in Taiwan it was more benign" -- and show that "the Taiwanese relationship with the colonizers was more conciliatory, while the Korean one was more confrontational" (page 61). The notion that the implementation of policies if not al the policies themselves were "harsher" and "more confrontational" in Chōen is so common as to be a cliché. However, Chou's generation is a much too simple and static understanding of differences in the family law issues that the government-generals of Taiwan and Chōsen were independently addressing in 1940.

Japan's incorporation of Taiwan in 1895 began and developed very differently than its annexation of Korea as Chōsen in 1910. The differences are such that conditions and experiences in one territory have practically no relevance to those in the other territory. Chou cites a number of significant differences in both conditions and experiences, but they too are among the more steretypic "commonly held" views.

She might have observed that Chōsen was much closer to the Interior geographically, and territorially it had been intimately involved in Japan's economic and political ventures in Manchuria. More importantly, though, Chōsen's fairly homogeneous population was regarded as being racioethnically very close to that of the prefectural Interior. Apart from the intimacy of contacts in earlier times, the rate of migration between Chōsen and the Interior had been increasing, and the populations of the two territories had begun to socially mix and even intermarry -- whereas, in contrast, Taiwan remained geographically and demographically more remote.

In the late 1930s, there was much more potential for the integration of Chōsen, than of Taiwan, into the Interior legal system, for the purpose of facilitating social and demographic mobility and amalgamation. There was therefore more interest in putting Chōsen family registers on a legal par with Interior registers -- hence the introduction in Chōsen of the Interior standard of one family name per household.

Chou's descriptions of "The Name-Changing Campaign" in Chōsen are better than most. But she does not very accurately describe the actual workings of related ordinances, as opposed to the extralegal manner in which some local authorities persuaded some people to declare name changes that the ordinances did not require.

Translations

All of the translations are mine, and they are structural. By this I mean that they attempt to reflect the phrasing and terminology as precisely as possible. This means that all key words and like phrases will be rendered the same. It also means retaining the viewpoint of the original text -- whether "legal" or otherwise.

See Linguistic discrepancies in the "Legal terminology" section of the "Glossaries" feature of this website for a closer look at point-of-view issues in writing generally and translation in particular.

Decree No. 19 of 1939

In 1939, the Governor-General of Chosen issued Decree No. 19 concerning "revision in Chōsen Civil Matters Ordinance".

|

昭和14年制令第19号 1939 Decree No. 19 |

|

|

朝鮮民事令中改正ノ件 Matters for revision in Chōsen Civil Matters Ordinance |

|

|

昭和十四年十一月十日

朝鮮総督 南 治朗 |

10 November 1939

Governor-General of Chosen Minami Jir#ō |

| This decree was promulgated on 10 November 1939 and enforced from 11 February 1940. | |

| Purpose of decree | |

| 朝鮮民事令中左ノ通改正ス | [This decree] revises [matters] in the Civil Matters Ordinance as [specified] to the left [below] |

| Family name provision | |

|

第11条第1項中「但シ」ノ下ニ「氏、」ヲ「認知、」ノ下ニ「裁判上ノ離縁、婿養子縁組ノ場合ニ於テ婚姻又ハ縁組カ無効ナルトキ又ハ取消サレタルトキニ於ケル縁組又ハ婚姻ノ取消、」ヲ加へ同条2左ノ一項ヲ加フ

氏ハ戸主(法定代理人アルトキハ法定代理人)之ヲ定ム |

In Article 11 Paragraph 1 add "family names," beneath "However" and "a judicial dissolution, an annulment of an alliance or a marriage when in the event of an adopted son-in-law alliance a marriage or an alliance becomes null and void or when it has been annulled,"; and in the same article add the paragraph [shown] to the left [below].

As for the family name, the head of houshold (when there is a legal representative, the legal representative) will determine this. |

| Adopted-son provisions added | |

|

第11条ノ2ヲ第11条ノ3トシ以下第11条ノ8迄順次一条宛繰下グ

第11条ノ2 朝鮮人ノ養子縁組ニ在リテ養子ハ養親ト姓ヲ同ジクスルコトヲ要セス但シ死後養子ノ場合ニ於テハ此ノ限ニ在ラス 婿養子縁組ハ養子縁組ノ届出ト同時ニ婚姻ノ提出ヲ為スニ因リテ其ノ効力ヲ生ス 婿養子ハ妻ノ家ニ入ル 婿養子離縁又ハ縁組ノ取消ニ因リ其ノ家ヲ去ルモ家女ノ直系卑属ハ其ノ家ヲ去ルコトナク胎兒生レタルトキハ其ノ家ニ入ル |

Make Article 11-2 Article 11-3 and below this to Article 11-8 move down one article each in turn.

Article 11-2 In adopted-son alliances of Chosenese, as for the adopted son, [the surname of the adopted son] need not be the same as the surname of the adoptive parent. However, in the event of a posthumous adopted son [this stipulation] will not apply. As for an adopted-son-in-law alliance, its effects will be borne by making a tendering of marriage at the same time as submitting the notification of an adopted-son alliance. The adopted son-in-law will enter the family of the wife. As for dissolutions of an adopted-son-in-law [alliance], although on account of an annulment of the alliance [the man] will leave the family, a lineal descendant of a family woman will not leave the family and at which time a fetus is born [it] will enter that family. |

adopted sons and adopted sons-in-lawFamilies that had no sons, or which had a son who was not capable of becoming the the head of the household, could adopt a son who stood to be the principle male heir. In Korea, such sons were supposed to be, if not a close relative with the same clan surname, then someone else with the same clan surname. In Japan, families without sons also adopted relatives, but they were free to adopt any one -- even aliens -- to succeed a head of household, before or after his death. In Korea, the idea of keeping the male line within the clan was to ensure the lineal integrity of the family. Future generations of a family would always be lineal descendants of its earlier generations. Blood was everything. In Japan, however, the name of the family was more important than blood ties when it came to survival of a family as a corporate entity. A son adopted as a child from an unrelated family might later marry someone outside the family. In which case future generations would have no lineal ties with past generations. Yet the family would survive in name and tradition. Adopted husbandsIn some cases, a son was adopted as part of an alliance to marry a daughter, thus keeping the blood-line going. An adopted son-in-law is usually referred to as an "adopted husband" -- a term that became better known through "An Adopted Husband" -- the English title of the translation of Sono omokage (其面影) by Futabatei Shimei (二葉亭四迷 1864-1909). The novel, published in 1906 after newspaper serialization, appeared in translation in 1919. Futabatei's story involves the Ono family, which has a daughter but no son. The head of the household adopts a university student and pays for his schooling, in return for which the young man agrees to marry Ono's daughter and carry on the family name. Ono Tetsuya, however, falls in love with his adoptive wife's younger sister. De facto husband adoption todayAdopted-son alliances are no longer possible under Japanese family law. However, the civil code mandates that a married couple to register in either the man's or woman's register. And this permits a family with no male heirs to effectively "adopt" a son-in-law who agrees to its egister. A marriage is recognized in Japan only when a couple are recorded as husband and wife in the same family register. Since everyone in the same register bears the same family name, unless a man and woman happen to have the same family name before they marry, one will have to assume the other's family name. Most women chose to enter the man's register, thus assuming his family name. In a small percentage of all marriages, the man enters the woman's register and assumes her name. Most cases in which the man enters the woman's register probably reflect a de facto "adopted husband" marriage, whether or not it was arranged as such. family womanA "family woman" (家女 kajo) was a woman who had been born into a family as opposed to one who had married into a family. The term was used in articles of Japan's 1896 Civil Code concerning the adoption of a son as an heir, sometimes involivng an alliance with a daughter in the family. The term and its concept vanished when the code was revised after World War II to eliminated privileges of gender and sibling status within families. The term "family" (家 ie) as a legal (corporate) entity was also abolished. In other words, Japanese law no longer recognizes a "family system" (家制度 ie seido). It recognizes only "households" (戸 ko) consisting of members who may be related to each other through lineage, marriage, or adoption. The "household" no longer constitutes a "corporation". Default inheritance, in the evenet there is no will, continues to be based on lineage and marriage, but no longer favors gender or sibling status. The 1948 Civil Code uses the character (家) in only two expressions -- "family court" (家庭裁判 katei saiban) and "family matter proceedings law" (家事審判法 kaji shinpan hō). |

|

| Other revisions | |

| 第11条ノ9ヲ第11条ノ10トシ同条中「第11条ノ3及第11条ノ4」ヲ「第11条ノ4及第11条ノ5」ニ改ム | Make Article 11-9 Article 11-10, and in the same article revise "Article 11-3 and Article 11-4" to "Article 11-4 and Article 11-5". |

| 附則 | Supplementary provisions |

|

本令施行ノ期日ハ朝鮮総督之ヲ定ム

朝鮮人戸主(法定代理人アルトキハ法定代理人)ハ本令施行後六月内ニ新ニ氏ヲ定メ之ヲ府尹又ハ邑面長ニ届出ヅルコトヲ要ス 前項ノ規定ニ依ル届出ヲ為サザルトキハ本令施行ノ際ニ於ケル戸主ノ姓ヲ以テ氏トス但シ一家ヲ創立シタルニ非ザル女戸主ナルトキ又ハ戸主相続人分明ナラザルトキハ前男戸主ノ姓ヲ以テ氏トス |

The Governor-General of Chosen will determine the day of enforcement of this decree.

[This decree] requires a Chosenese head of household (when there is a legal representative, the legal representative) to newly determine a family name within six months after the enforcement of this decree, and to submit notification of this to the mayor of a city head or headman of a township. When [a head of household] does not make a submission of notification in accordance with the preceding item, [the registrar] will take as the family name the surname of the head of household at the time of this decree's enforcement. However, when a female head of household has not established a family, or when the successor to the head of household is not clear, [the registrar] will take as the family name the surname of previous male head of household. |

Decree No. 20 of 1939

In 1939, the Government-General of Chosen issued Decree No. 20 concerning "family and personal names of Chosenese".

| 1939 Decree No. 20 on family and personal names of Chosenese | |

| This decree was promulgated on 24 November 1939 and enforced from 11 February 1940. | |

|

朝鮮人ノ氏名ニ関スル件

Matters concerning family and personal names of Chosenese |

|

|

昭和14年 朝鮮総督府制令第20号 |

Showa 14 (1939) Government-General of Chosen Decree No. 20 |

|

第一条

御歴代御諱又ハ御名ハ之ヲ氏又ハ名ニ用フルコトヲ得ズ 2 自己ノ姓以外ノ姓ハ氏トシテ之ヲ用フルコトヲ得ズ但シ一家創立ノ場合ニ於テハ此ノ限ニ在ラズ |

Article 1

As for the (honorable) posthumous names and (honorable) personal names of (honorable) historical generations [i.e., successions] [of emperors and empresses], [this decree] does not enable [one] to use these as a family name or a personal name. 2. As for a surname other than one's own surname, [this decree] does not enable [one] to use it as a family name. However, in the event of the founding of a [new] family, [this stipulation] will not apply. [ == Provided, however, that this will not apply in the event of establishing a new family.] |

Lese majestyThe Nakano Bunko text has 得ス (enables), which seems to be a transcription or scanning error. I am following a thesis which has 得ズ (does not enable) and remarks that "This [Decree No. 20] indicates a restriction with respect to family name establishment, in that it prohibits disrespectful (不敬 fukei) family names and personal names and other surnames and family names " (I Hohyon 2005). Source Page 134 of Part 2 of a doctoral thesis apparently submitted by I Hohyon (李 [ホ] 鉉) (sic) in 2005 to the Faculty of Education and Integrated Arts and Sciences at Waseda University. The title of the thesis is 植民地朝鮮の社会教化と文化変容に関する研究 : 戦時ファシズム期の庶民の生活実情を中心に (Shokuminchi Chōsen no shakai kyōka to bunka hen'yō ni kan suru kenkyū: Senji fashizumu-ki no shomin no seikatsu jitsujō o chūshin ni) or "A study concerning the social enlightenment and cultural change in colony Chōsen: Centering on the conditions of life of the common people in the war-time facist period". The thesis is posted on Waseda's DSpace site, which accommodates faculty and staff publications. This is consistent with other lese majesty (不敬罪 fukeizai) laws in Japan at the time. Names of emperors and empressesHowever, Paragraph 1 is structured much like a proclamation issued by the Great Council of State shortly after the start of the Meiji period -- which permitted commoners to use the characters of imperial names. The proclamation, made in 1873 on the heels of the enforcement of the 1871 Family Registration Law, addressed the attempts of few people, among the masses who had not had family names, to adopt the names of historical dignitaries, particarly emperors and empresses (text from Nakano Bunko, translation mine). 明治六年 Meiji 6 (1873) This proclamation was abrogated by Article 138 of the Family Registration Law promulgated on 22 December 1947 (Law No. 224). This law, enforced from 1 January 1948, replaced the 1871 law. It is not clear whether the Meiji proclamation is permitting use of imperial names themselves, or only characters that have been used in such names. |

|

|

第二条

氏名ハ之ヲ変更スルコトヲ得ズ但シ正当ノ事由アル場合ニ於テ朝鮮総督ノ定ムル所ニ依リ許可ヲ受ケタルトキハ此ノ限ニ在ラズ |

Article 2

As for family names and personal names, [this decree] does not enable [one] to change them. However, when [one] has received permision [to change a name] in accordance with a determination of the Governor-General in the event there is justifiable cause [reason], [this stipulation] will not apply. |

Name-change petitionsThe provision prohibiting name changes, except as permitted through petition, arcs back to the early Meiji period, when the Great Council of State had to deal with name problems that emerged after the enforcement of the 1871 Family Registration Law. 明治5年8月24日 Meiji 5-8-24 (26 September 1872) This proclamation was abrogated by Article 138 of the Family Registration Law promulgated on 22 December 1947 (Law No. 224). This law, enforced from 1 January 1948, replaced the 1871 law. |

|

| 附則 | Supplementary provisions |

| 本令施行ノ期日ハ朝鮮総督之ヲ定ム | The Governor-General of Chosen will determine the day of enforcement of this decree. |

Ordinance No. 221 of 1939

In 1939, the Government-General of Chosen issued Ordinance No. 221 concerning "procedures for submission of notices and records in household registers concomitant with the establishment of family names of Chosenese".

| 1939 Ordinance No. 221 on name change notifications and register entries | |

|

This ordinance was promulgated on 26 December 1939 and came into force on 11 February 1940. |

|

|

朝鮮人ノ氏ノ設定ニ伴フ届出及戸籍ノ記載手続ニ関スル件

Matters concerning procedures for submission of notices and records in household registers concomitant with the establishment of family names of Chosenese |

|

|

昭和14年 朝鮮総督府令第221号 |

Showa 14 (1939) Government-General of Chosen Decree No. 221 |

|

第一条

氏ノ設定ニ伴フ届出及戸籍ノ記載手続ニ付テハ本令ニ定ムルモノノ外朝鮮戸籍令ノ規定ニ依ル |

Article 1

With respect to procedures for submission of notifications and records in household registers concomittant with the establishment of a family name, they will be in accordance with, other than what is determined by this ordinance, provisions in the Chōsen Family Register Decree. |

|

第二条

氏ノ届出ハ書面ヲ以テ之ヲ為スベシ 2 届書ニハ左ノ事項ヲ記載スベシ 一 戸主ノ姓名、出生ノ年月日、本籍及職業 二 氏 |

Article 2

As for the submission of a notification of family name, [one] must do this with a document. 2. On the document, [one] must record the particulars to the left [below]. (1) the head of household's surname; year, month, and day of birth; [place] of principal register; and occupation (2) family name |

|

第三条

昭和十四年制令第十九号附則第三項ノ規定ニ依リ戸主又ハ前男戸主ノ姓ヲ以テ氏トシタルトキハ戸籍ノ記載ハ訂正セラレタルモノト看做ス但シ更正スルコトヲ妨ゲズ 2 戸籍ノ記載事項中家ヲ異ニスル者ノ氏定マリタルトキ亦前項ニ同ジ |

Article 3

When taking for the family name the surname of the head of household or the previous male head of household in accordance with the provision of Paragraph 3 of the Supplementary Provisions of Decree No. 19 of Showa 14 (1939), the record of the household register will be viewed as something which has been corrected. However, [this ordinance] will not prevent rectifying [the record]. 2. When [one has determined] the family name of someone who differs from the family in the record particulars of the household register, [the matter will be treated] the same as in the preceding paragraph. |

| 附則 | Supplementary provisions |

| 本令ハ昭和十四年制令第十九号施行ノ日ヨリ之ヲ施行ス | This ordinance will be enforced from the day of enforcement of Decree No. 19 of Showa 14 (1939). |

Ordinance No. 222 of 1939

In 1939, the Government-General of Chosen issued Ordinance No. 222 concerning "changes of family names and personal names of Chosenese".

| 1939 Ordinance No. 222 on name changes | |

| This ordinance was promulgated on 26 December 1939 and enforced from 11 February 1940. | |

|

朝鮮人ノ氏名変更ニ関スル件

Matters concerning changes of family names and personal names of Chosenese |

|

|

昭和14年 朝鮮総督府令第222号 |

Showa 14 (1939) Government-General of Chosen Decree No. 222 |

|

第一条

氏名ノ変更ヲ為サントスル者ハ其ノ本籍地又ハ住所地ヲ管轄スル裁判所ニ申請シテ許可ヲ受クベシ 2 不許可ノ裁判ニ対シテハ不服ヲ申立ツルコトヲ得ズ |

Article 1

As for those who would effect a change of [their] family name [and or] personal name, [one] must receive permission by applying to the court which has jurisdiction over one's place of principal register or place of residence. 2. [This ordinance] does not enable [one] to file a complaint against a judgment of non-permission. |

|

第二条

許可ノ申請ハ書面ヲ以テ之ヲ為スベシ 2 申請書ニハ左ノ事項ヲ記載シ戸籍謄本ヲ添附スベシ 一 本籍、住所、氏名、出生ノ年月日及職業 二 変更セントスル氏名 三 変更ノ理由 |

Article 2

As for the application for permission, [one] must do this with a document. 2. On the document, [one] must record the particulars to the left [below] and attach a copy of [one's] household register. (1) [place of] principal register; address; family name and personal name; year, month, and day of birth; and occupation (2) the family name [and or] personal name [one] would change (3) the cause [reason] for the change |

|

第三条

許可ノ申請ヲ為スニハ手数料トシテ五十銭ヲ納付スルコトヲ要ス 2 前項ノ手数料ハ収入印紙ヲ以テ之ヲ納ムベシ |

Article 3

In making an application for permission, [this ordinance] requires the payment of 50 sen as a service fee. 2. [The applicant] will pay the service fee of the preceding paragraph with a revenue stamp. |