1872 Family Register Law

Japan's first "law of the land"

By William Wetherall

First posted 1 April 2008

Last updated 1 May 2021

Family registers as boundaries of the nation

People (jinmin)

•

Nationals (kokumin)

•

Subjects (shinmin)

Chronology of Meiji population registers

A timeline of major political, legal, and administrative actions and reforms

1871 GCS Proclamation (No. 170)

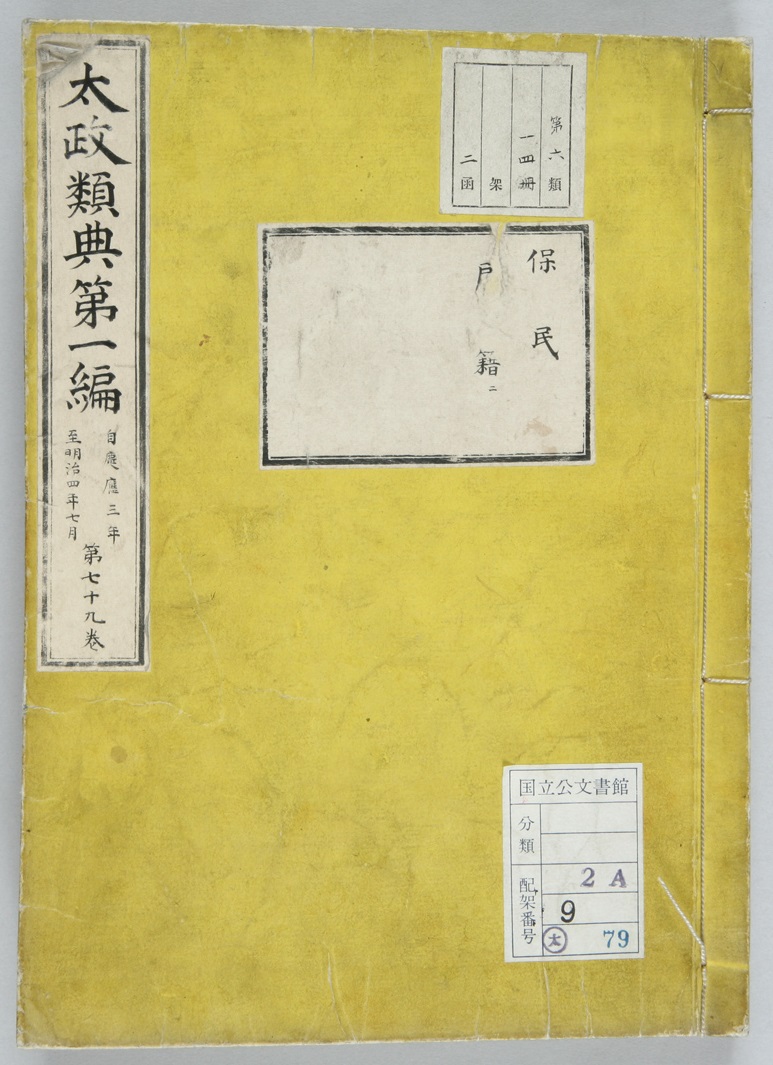

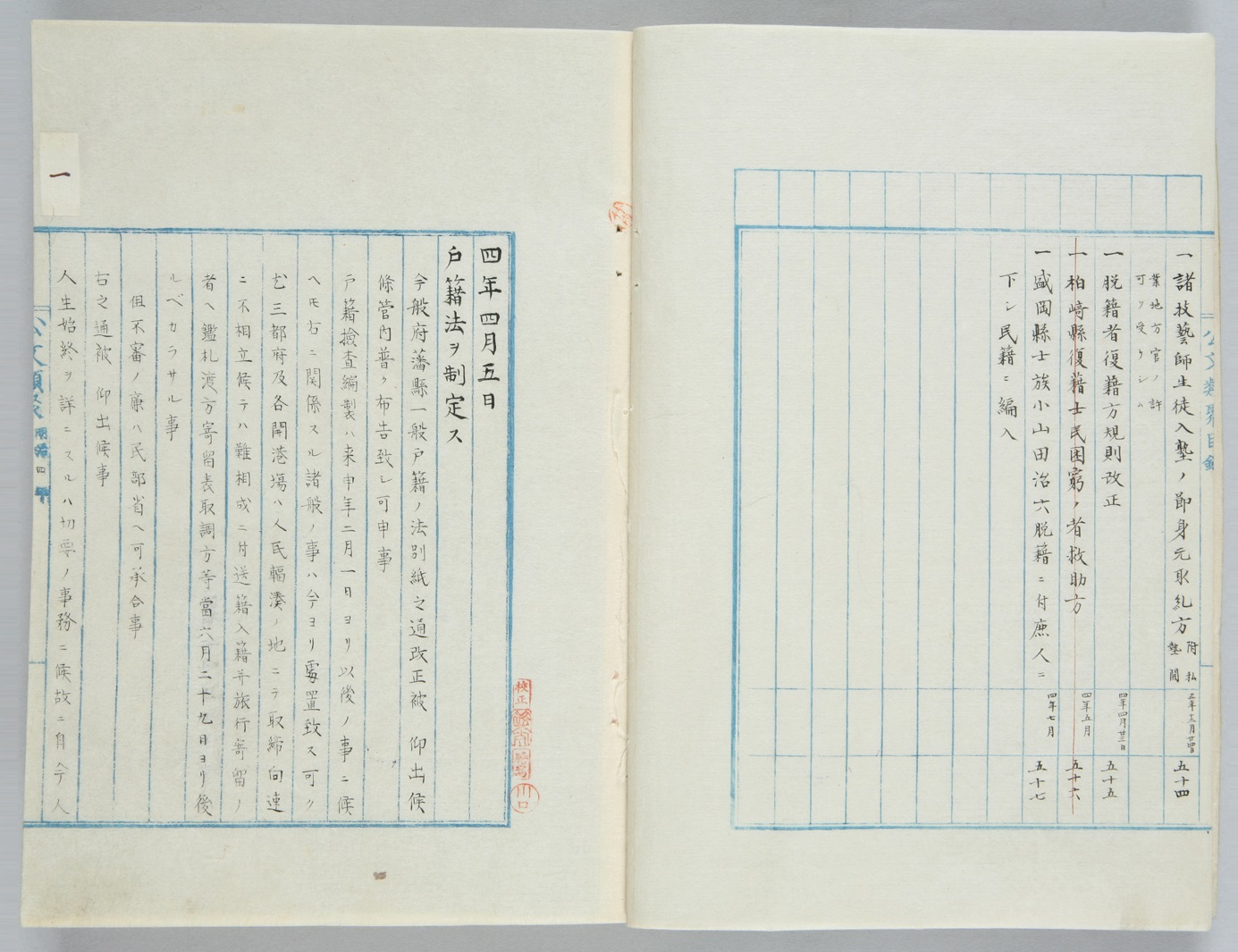

Dajō ruiten images

•

Preamble

•

Article 1: Subjects at large

•

Article 32: Eta hinin etc.

1872 Jinshin register statistics

Households by sex of heads, and persons by sex, by status

Meiji-era household registration handbooks

Aoki & Takasaki 1877

•

Matsuura 1877

•

Noguchi 1893

•

Okamoto 1898

•

Mori & Endo 1898

•

Endo 1898

Related articles

The Interior: The legal cornerstone of the Empire of Japan

Minseki registers, 1868-1945: The nation defined as demographic territory

Belonging in Japan past and Present: Before and after "nationality" and "citizenship"

Affiliation and status in Korea: 1909 People's Register Law and enforcement regulations

Affiliation and status in Manchoukuo: 1940 Provisional People's Register Law and enforcement regulations

Family registers as boundaries of nation

Law has been an important means of social organization and control in Japan for the better part of a millennium and a half. Population registration has been the most effective way of shepherding local populations as part of the aggregate national population.

The first mission of the imperial order that replaced the Tokugawa Shogunate in 1868 was to nationalize the domains and their people into a nation. The second mission was to create a new system of laws with which the state could govern and protect the nation.

First the domains were replaced by prefectures. Then local polities were given a means of controlling their populations, for the sake of the nation as well as to facilitate their own governmental needs.

The Family Register Law of 1871, effective in 1872, became -- in many respects -- the new country's most fundamental law, which I regard as Japan's "law of the land" -- without which there would be no Japan as the world knows it. Fashioned on a variety of population registration practices known for over a millennium, the Family Register Law gave localities the means of harnessing their inhabitants to the wagon of the new state.

Family registers also served to define the nation. If the prefectures delimited Japan's geographical territory, municipal family registers marked the borders of its demographic territory.

Family registration is about families. Birth and death, and alliances and dissolutions of marriage and adoption, are about families, and therefore involve family registration. Hence Meiji laws concerning Japanese alliances of marriage and adoption with foreigners rested on the foundations of Japanese family law and family registration practices.

For an overview how family law, administered through family registration, was used to resolve issues that arose when a Japanese wished to marry or adopt a foreigner, see 1873 intermarriage proclamation: Family law and "the standing of being Japanese.

For a look at later developments in the Family Register Law, and at the development of the Civil Code, which embodies the family laws that govern the Family Register Law and the Nationality Law, see the Family Register Law section of The Interior: The legal cornerstone of imperialism.

Jinmin �l�� people

The graphic term �l�� -- a Chinese compound -- has been widely used in Japan over the centuries, with various readings, to mean "people" affiliated with a sovereign or local authority. The term was last used in Japan's status laws, to refer to people affiliated with Japan's population registers, in the late 19th century.

"Jinmin" in early Japan

Graphically, �l�� appears in early texts like Kojiki (712), the earliest surviving history -- Nihon shoki (720), the first of a series of official national histories -- Shinsen shōjiroku (815), a peerage of titled families -- and Wamyō ruiju shō (938), a dictionary of Japanese words written in Chinese graphs.

Two Yamato expressions are associated with the graphs �l�� as used in these early texts.

hitokusa �q�g�N�T ��~�v�� (�l��)

wohotakara ���z�^�J�� ���ۑ���� (���)

Kojiki uses �l�� several times, such as in "defeated the people (human grass) of the country" (kuni no hitokusa �������V�l��). It also uses �l�� several times, as in "the human grass of your country" (�V�l��).

For examples of earlier terms referring to the "people" of Japan, see Belonging in Japan past and present under "Nationality Laws" on this website.

1871 Family Register Law

The 1871 Family Register Law uses three terms to signify demographic belonging to Japan -- jinmin (�l��), kokumin (����), and shinmin (�b��) -- all of which use the word "min" (��), which means affiliate. Jinmin (affiliated people) and kokumin (nationals) are used in the prologue (see transcription and translations below). Shinmin (subjects) is used and defined in the Article 1 (see below).

"Jinmin" in 1876 Japan-Chosen treaty

The 1876 Kanghwa treaty between Japan and Chosen, for example, refers to the "people" of the party states as follows, citing the Chinese and English versions of the treaty. See transcriptions and translations of treaty in 1876 Kanghwa treaty between Japan and Chosen in the "Korea becomes Chosen" article under "The Sovereign Empire" in the "The Empires of Japan" section of this website.

���N���l�� (Chōsen-koku jinmin) "subject of Chosen"

���{���l�� (Nihon-koku jinmin) "Japanese subject"

Usage has somewhat changed by the 1882 Yin-chuen (Shufeldt) treaty between United States and Chosen. What the English version variously calls "citizens" of the United States and "subjects" of Chosen are referred to as ���N���l (Chōsen minjin) and �������l (Mikoku minjin) in the Chinese version. "Minjin" (���l) is used like "jinmin" (�l��) to denote "affilated people". "Nationality" in the English version is reflected as ���� (affiliation) in the Chinese version, hence phrases like �����V�� (shozoku no kuni) or "country of affiliation". Here "sho" (��) is used with "zoku" (��), meaning to affiliate, to form a typical "�� + V" compound. As a nominalized passive construction, "shozoku" means "condition of being affilated [something]" "shozoku" (����) means "(condition of) being affiliated (with a country or other entity)". See transcriptions and translations of treaty in 1882 Yin-chuen (Shufeldt) treaty between United States and Chosen (Korea) (ibid.) for details.

Keep in mind that, as of 1876 and 1878, Japan did not yet have a Constitution or Nationality Law. "Nationality" was not yet that widely used in English as a term for affiliation with a state, and this sense of the word would not come to be translated "kokuseki" (����) until later. "Shinmin" (�b��) was not fully established as the Japanese word for "subject" until the 1890 Constitution. The 1899 Nationality Law -- like the 1873 proclamation on alliances of marriage and adoption between Japanese and foreigners -- used "Nihonjin" (���{�l) rather than either "shinmin" or "kokumin" (����) to refer to people who possessed the "nationality" (����) of Japan.

Note that the English versions of both of the above treaties -- which were written in Chinese -- translated (transliterated) ���N as "Chosen".

"Jinmin" today

The Prologue of the 1871 Family Register Law speaks mainly of "jinmin". "Kokumin" (����) or "national" appears only once, and the articles of the law use "shinmin" (�b��) or "subject". The 1890 Constitution uses "shinmin", and other laws use "shinmin" or "kokumin" depending on the purpose of the law. But the 1899 Nationality Law, which might have used "shinmin" (given the provisions for the law in the 1890 Constitution, speaks of "Japanese" (Nihonjin ���{�l).

So by the 20th century, other terms had replaced "jinmin" in Japan's domestic legalese. Today the term appears mainly in the names of socialist counties like the People's Republic of China and the Democractic People's Republic of Korea (Chosen), which refer to their affiliates as "citizens" (kōmin ����) rather than "nationals" (kokumin ����), a term which they eschew as anti-communist.

Kokumin ���� nationals

"Kokumin" (����) or "national" is used only once in the 1871 Family Register Law, and only in the Prologue. It does not appear in the 1890 Constitution, which refers to people who owe allegiance to the sovereign as "shinmin" (�b��) meaning "loyal people" or "loyal affiliates". Even the 1899 Nationality Law does not use "national" but only "Japanese".

However, "kokumin" is the status term in many laws that stress affiliation with the state rather than imperial subjecthood. "Nationals" are essentially defined as people in household registers affiliated with Japan's sovereign dominion. However, "shinmin" (�b��) meaning "subjects" -- not "kokumin" -- was the term used in the articles of the 1871 Family Register Law to refer to registrants. While the terms differed metaphorically, they were generally synonymous as labels for people considered legally "Japanese".

The Allied Powers, when occupying Japan in 1945, immediately declared that the people of Japan were no longer "shinmin". They couldn't be, because the emperor was no longer a sovereign. From 2 September 1945, all people in Occupied Japan, beginning with the emperor, were subject to the authority of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP).

From the start of the Occupation of Japan, the people of Japan became just "kokumin". In debate over the term to be used in a new constitution, "jinmin" (�l��) was rejected because, by then, it had acquired strongly socialist nuances. So the 1947 Constitution retained the term "kokumin". And the 1950 Nationality Law adopted the constitutional term "kokumin" in lieu of "Nihonjin".

Some people have argued that the use of "kokumin" the nationality law allowed the word "Nihonjin" to used to imply something racioethnic, unlike "kokumin", which was legally a purely civil status. This is not true. "Nihonjin" has always been available as both a civic and ethnoracial label. In no way does being a "kokumin" of Japan mean that one might not be "Japanese". As used by racialist speakers and writers, "Japanese" is a racioethnic label. In civil usage, "Japanese" means anyone who possesses Japan's nationality regardless of their putative race or ethnicity.

Shinmin �b�� subjects

This term defined the essential status of the people of Japan from its use in the 1871 Family Register Law to its loss of legal standing in 1945, when the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers disallowed its use. It remained the 1890 Meiji Constitution (but was understood to mean "kokumin") until replaced by "kokumin" in the 1947 Shōwa Constitution. And "shinmin" was replaced by "kokumin" in all laws that had used it.

The Prologue speaks of "kokumin" only once but "jinmin" many times. And "jinmin" -- not "kokumin" or "shinmin" -- would be used in a number of early documents, including international treaters, to refer to the "people" of Japan and other countries.

Chronology of Meiji population registers

A timeline of major political, legal, and administrative actions and reforms

Family registers were established at a time when the new Meiji government was rapidly changing to deal with the challenges of defining and serving the needs of the people of Japan as a team of horses rather than as a herd -- as prefectures harnessed together and driven as one to pull a single load -- the emperor's realm -- rather than as a loose confederation of local domains that didn't share a common national banner and purpose -- to protect the realm and prosper. No institutions, and no individuals, were spared the imperatives of change and the difficulties that come with navigating through uncharted waters.

The many domains gave way to fewer prefectures. But still, there were too many territories, and many prefectures would be merged or their boundaries otherwise change.

Long-established social castes and classes were abolished with the stroke of a brush, in favor of newer statuses, in the interest of reducing the privilges of some and increasing the freedoms of others. Then some of the new statuses were modified and reduced in number, in the interest of creating a society of commoners and nobility overseen through uniform household population registers, and an imperial family it its own registers.

A millennium of collective bureaucratic experience, maintaining a semblance of order in an expanding realm that was often torn by succession wars within the imperial house, or territorial wars between rival domains and coalitions of domains, paid off. The new leaders came mainly from the ranks of the samurai who had led their domains, or factions within their domains, in rebellion against the Tokugawa domain -- which was finally pressured to give up its long dynastic rule in favor of restoring to the seat of symbolic power a teenage emperor whose sole reign name became Meiji.

Sporadic civil uprisings continued for a decade into the Meiji era, but the country quickly settled into a period of rapid learning and development, and by the 1890s it had established a legal system that convinced its unequal treaty partners to end their extraterritorial rights in Japan.

By the start of the 20th century, Japan had a national administrative system that, as bureaucracies go, actually worked pretty well. For the most part, the prefectural household registration system became more efficient as it accommodating the registration systems in the territories Japan acquired through cessions following wars and annexations. The new territories -- Taiwan, Karafuto, and Chōsen -- were from their start integral parts of Japan's sovereign dominion. And as years became decades, they lost their initial "colonial" qualities and became virtual extensions of the prefectural Interior. Karafuto even became a prefecture, and Taiwan and Chosen became increasingly integrated into the political, economic, legal, social, and cultural revolutions that affected the Interior.

The following chronology lists only the most prominent events, reforms, and bureaucratic actions and appointments that characterize the conditions surrounding the implementation and management of household registers pursuant to the Family Register Law, on which many later laws would depend.

3 January 1868 (Keiō 3-12-9) Formal proclamation of abolishment of the consignment of the right to rule to a military house (Tokugawa domain) and the nominal restoration of absolute sovereignty to the emperor -- nominal because, while the emperor would have the authority to directly rule the country, his rule would be orchestrated and mediated by others.

23 October 1868 (Keiō 4-9-8) [Meiji 1-9-8] Mutushito formally ascends the imperial throne under a new reign name -- Meiji. reign name Meiji, marking the official start of Meiji period and the restoration of the emperor to the de jure seat of power.

On 15 August 1869 (Meiji 2-7-8), as a result of revamping existing government offices, the "People's Ministry" (Minbushō ������) and "Treasury Ministry" (Ōkurashō �呠��) were established within the Great Coucil of State (Dajōkan ������). The People's Ministry was responsible for overseeing administration of affairs in all regions of the country, while the Treasury Ministry was responsible for collecting taxes throughout the country, so on 16 September 1869 (Meiji 2-8-11), a month later, the two ministries were merged. on 10 July 1870, however, the they were separated. Both ministries underwent change in the bureaucratic turf wars, with the result that, on 11 September 1871 (Meiji 4-7-27), the People's Ministry was merged into the Treasury Ministry and thereby abolished.

As promulgated on 22/23 May 1871 (Meiji 4-4-4/5), Japan's first Family Register Law called for household registers to be made by local registrars and results submitted to (initially) the People's Ministry. By 9 March 1872 (Meiji 5-2-1), when the Family Register Law came into force, the Treasury Ministry was responsible for the overseeing of household registers.

the two agencies were merged for which was responsible for administering domestic affairsin [Kanpō promulgation] 1871�N5��23���i����4�N4��5���j, which came into force in 1872, household registers were established within a nationwide grid of numbered regions called "ku" (��). From 1872-5-15 (Meiji 5��15���i����5�N4��9���jBy , which were made up of several villages (mura ��), and towns (machi ��) and villages (mura ��). The heads (kochō �˒� and sub-heads (fuku-kochō ���˒�) of such administrative entities were responsible for overseeing the establishment of registers within their jurisdictions., called within a nationwide grid of "ku" (��). -- according towere initially overseen by pursuant to the eFamily Register Law 1871-5-22 (Meiji 4-4-4) - 1872 "large ku" (dai-ku ���), "small ku" (shō-ku ����) 1872-6-10 (Meiji 5-4-9) 1878�N����1889�N�܂œs�s���ɐ݂���ꂽ�n���敪�B�u�S�撬���Ґ��@�v���Q�ƁB 1889�N����1947�N�܂Œ��߂Ŏw�肳�ꂽ�����s�A���s�s�A���s�ɐ݂���ꂽ�n���敪�B�O���̋�������p���A�e�s�i1943�N7��1���ȍ~�A�����s�͓����s�j�̉��ʂ̒n�������̂Ƃ��ꂽ|

Chronology of Meiji population registers |

|||

| Tokugawa-Meiji transition | |||

|

10 January 1867 |

Tokugawa Yoshinobu (����c�� 1837-1913, s. 1867-1868) becomes the 15th shōgun in a dynastic succession of Tokugawa shōgun that began with Tokugawa Ieyasu (����ƍN 1543-1616, s. 603-1605). Ieyasu received the title as an hereditary status from Emperor Go-Yōzei (��z�� 1571-1617, r. 1586-1611) on 24 March 1603 (Keichō 8-1-12). This date marks the formal start of the Tokugawa shogunate in Edo, where Ieyasu established a "tent government" (bakufu ���{) -- hence the Tokugawa period is also called the Edo period, and its government is commonly referred to as the "Tokugawa bakufu". The Tokugawa clan became the dominant military family in Japan after Ieyasu's victory at the Battle of Sekigahara on 21 October 1600 (Keichō 5-9-15). The battle all but ended decades of civil unrest and wars. The relative peace for which the period was marred by the siege of Ōsaka Castle in 1614-1615 and the Shimabara Rebellion of 1637-1638. And such peace as was generally realized came at the expense of strictly enforced social policies within the country, restricted trade, and practically closed borders. "Shōgun" is short for "Subdue-natives great-general" or "Great native-subduing general" (Sei-i tai-shōgun ���Α叫�R), a military title going back to the 8th century. As a title signifying that the bearer was the acting sovereign of the country, it goes back to the 12 century. As a title for a military commander who was ordered to actually subdue natives, it goes back to the reign of Emperor Kanmu (���� 736-806, r. 781-806), who dispatched forces to conquer and govern the people who inhabited the northeastern reaches of Honshū. Subduing the frontier lands facilitated migrations of Yamato people to northeast, where they mixed with the local people, generally known as Emishi (�ڈ�). I regard the term as a generic appellation for what seem to have been the descendants of migrations from the continent of Northeast Asia, which preceded the migrations of Yamato ancestors, who mixed with local peoples in the southwestern reaches of what later became Japan. See Akihito's Korean roots for more about Emperor Kanmu. |

||

|

13 February 1867 |

14-year-old prince Mutsuhito succeeds his father Osahito (Kōmei) as emperor. Keiō -- the last of the 7 imperial era names established during Osahito's reign -- changed to Meiji 20 months later, on 23 October 1868, a week after Mutsuhito's formal enthronment on 12 October 1868. |

||

|

9 November 1867 |

Shōgun Tokugawa Yoshinobu formally resigns his title as shōgun to emperor Mutsuhito, effective 10 days later on 19 November 1867 (Keiō 3-10-24). |

||

|

3 January 1868 |

Mutsuhito issues decree of restoration of imperial rule, in which he acknowledges that he has accepted the shōgun's resignation of title and authority and would himself govern the country. From that point, foreign powers were to refer to the sovereign as and that he himself would tissues edict in whicFormal start of restoration government. |

||

|

27-30 January 1868 |

A coalition of pro-imperial forces route Tokugawa armies at Toba and Fushimi, near Kyōto, in the first battle of the Bōshin War, which sporadically continued until 27 June 1869 (Meiji 2-5-18). |

||

|

11 April 1868 |

The Tokugawa government surrenders Edo castle to pro-imperial forces, which have surrounded the castle. |

||

|

3 September 1868 |

Edo was formally renamed Tōkyō (����) or "eastern capital". Tokyo was then typically romanized "Tokio". For a while it was also called "Tōkei" and romanized "Tokei". It was also for a while written ���� rather than ����, to distinguish it from the much older "eastern capital" of Vietnam known as "Tonkin" (���� C. Tongking, Tonking, V. Dong Kinh, Đông Kinh), which later became Hanoi (�͓� C. Hanoi, V. Ha Noi, Hà Nội). |

||

|

12 October 1868 |

Mutsuhito enthroned at Kyoto Imperial Palace. His succession is celebrated at Daijōgū in Tokyo on 28 December 1871 (Meiji 4-11-17). |

||

|

23 October 1868 |

Imperial era name changes from Keiō to Meiji. |

||

|

9 February 1871 |

Shinritsu kōryō (�V���j��) or "Outline of new codes" [New-measures main-parts (neck of main rope of fishing net)], a provisional penal code, was promulgated by Great Council of State Proclamation No. 94 of Meiji 3-12-27 (16 February 1871). The new codes were supplemented by Kaitei ritsurei (���藥��) or "Amended codes" [Revised-determinations measures-rules] by Great Council of State Proclamation No. 206 of 13 June 1873 (Meiji 6-6-13). The 1871 law and its 1873 supplement were replaced from 1882 by Keihō (�Y�@), the first "Penal Code" by name. Promulgated by Great Council of State Proclamation No. 36 of 17 July 1880, this original Meiji law came into effect from 1 January 1882. As a penal code, Shinritsu kōryō needed to distinguish status relationships between family members, hence it's inclusion of a chart showing 5 degrees of kinship relationships, including statuses of "wife" and "mistress" as 2nd-degree kin. These relationships became the basis of relationships defined in family and civil laws. See Five degrees of relationship in 1871 Shinritsu kōryō. |

||

|

22/23 May 1871 |

Family Register Law promulgated by GCS Proclamation No. 170. The law called for local authorities to establish registers within their village and town jurisdictions, and to submit enumerations to (initially) the People's Ministry (Minbushō ������). By 9 March 1872 (Meiji 5-2-1), when the law came into effect, the Treasury Ministry (Ōkurashō) was responsible for overseeing of household register matters. |

||

|

12 October 1871 |

Two back-to-back Great Council of State proclamations concerned the statuses and registrations of eta, hinin, and other sub-castes and sub-classes. GCS No. 448 abolished the appellations of eta, hinin and such, and provided that their statuses and occupations were to be on a par with those of commoners (heimin). GCS No. 449 reiterated the abolishment of appelations and parity of treatment of status and occupation as commoners. It went on, however, to say that the Treasury Ministry would be looking into the prospects of changing the customary practice of exempting them from land taxes et cetera. See 1871 Eta and hinin integration (GCS Proclamations Nos. 448 and 449) for texts and translations. Note that these proclamations were issued nearly 5 months after the promulgation of the Family Register Law (above) and nearly 4 months before its enforcement (below), during which time the competent ministry changed from the People's Ministry to the Treasury Ministry. Note also that |

||

|

28 December 1871 |

Mutsu's succession (12 October 1868) is celebrated at Daijōgū in Tokyo. |

||

|

8 March 1872 |

The Family Register Law, which obliges the chiefs of local administrative divisions to create household registers pursuant to the law, comes into effect. |

||

|

9 March 1872 |

The Family Register Law, which obliges the chiefs of local administrative divisions to create household registers pursuant to the law, comes into effect. |

||

|

15 May 1872 |

Great Council of State Proclamation No. 115 provides that those who forfeit noble (kazoku) or gentry (shizoku) status may be enrolled in a general "people's register" (minseki). See 1872 Nobility and gentry migration to general registers. |

||

|

31 December 1872 |

Japanese government officially adopts the solar calendar by equating Meiji 5-12-3 (1 January 1873) on the lunar calendar with Meiji 6-1-1 (1 Janaury 1873) on the solar calendar. So the last official lunar calendar date was Meiji 5-12-2 (31 December 1872). Japan has used several lunar-solar calendars since the 7th century in the Christian era. The calendar in use at the time the Meiji period began was the Tenpō calendar (Tenpōreki �V�ۗ�), which was introduced from Tenpō 15-1-1 (18 February 1844). This calendar remained in private use for a while after the adoption of the solar calendar, especially in matters concerning religious and other events. Eventually, though, lunar dates of events were simply read as solar dates. Few lunar calendars are published in Japan today and most are sold as novelties. A few solar calendars show lunar dates in small print, but more likely they show only the names of the 6 days (rokuyō �Z�j) which in Buddhist reckoning vary in auspiciousness from very lucky to very unlucky, as many organizations and individuals today continue to schedule important events, such as ground breaking ceremonies or weddings, on the most auspicious days. However, there is little general awareness today of the astronomical significance of the present (solar) dates of lunar-calendar-era festivals, events, and incidents. The celebration of Tanabata on 7-7 (7 July), and the observance of O-bon centering on 7-15 traditionally, or 8-15 (15 August) today, come to mind. And practically no one I have talked with feels the oddness of featuring re-runs of 47-rōnin vendetta films or staging bunraku performances of Kanadehon Chūshingura on or around 14-15 December (see |

29 November 1873 |

Interior Affairs Ministry (������) created under Dajōkan government. Ōkubo Toshimichi becomes its first minister. The next 6 ministers -- 4 in quick succession -- were as follows.

2. 14 Feb 1874 - Kido Takayoshi (�،ˍF�� 1833-1877 Chōshū faction) |

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

14 March 1873 |

"Provisions permitting marriage with an alien person" (Gaikoku jinmin to kon'in sakyo jōki �O���l���m�����������K) promulgated by Great Council of State Proclamation No. 103. See 1873 intermarriage proclamation: Family law and "the standing of being Japanese". |

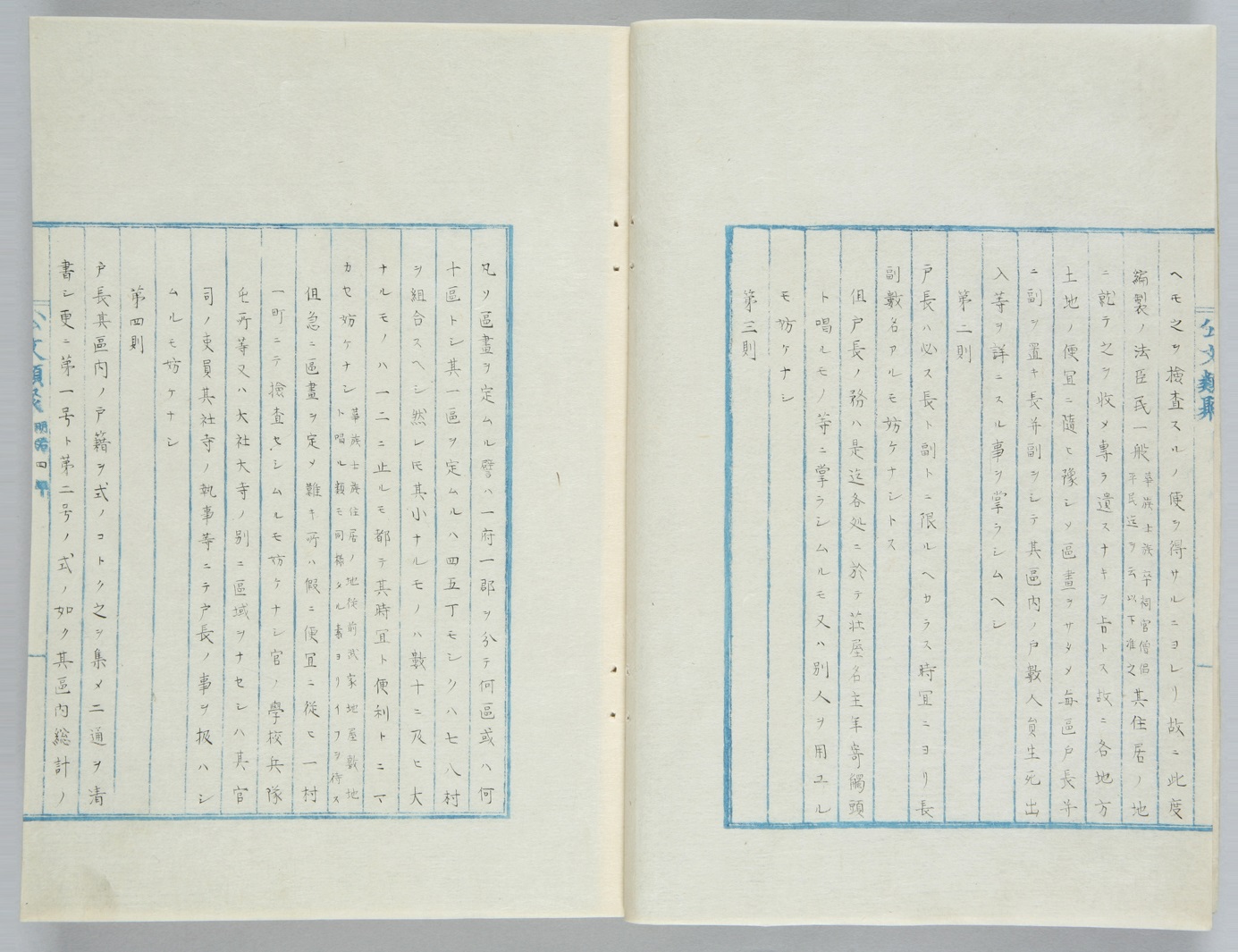

||

1871 GCS Proclamation No. 170Several proclamations were made during the early years of the Meiji period relating to social status, some concerning surveys, others about change. The first family registration law addressed the need to record data on people according to their status, and to compile and report local registration data. Promulgated by Great Council of State Proclamation No. 170 of Meiji 4-4-4 (22 May 1871), the register law was enforced from Meiji 5-2-1 (9 March 1872). �����S�N�S���S���������z����170�� Promulgated Meiji 4-4-4 (22 May 1871) by Enforced from Meiji 5-2-1 (9 March 1872) Sources�@�ߑS�� [��U��] �����S�N This first full version of various earlier drafts includes thirty-three articles stipulating rules for registering households and tabulating demographic (census) information. The rules are followed by examples of forms and tables that were to be used by local authorities when implementing the provisions of the proclamation and reporting census information to prefectural governments. �����ޓT���� Daijō ruiten Dai-ichi-hen Some writers give the promulgation date as Meiji 4-4-5 (23 May 1871). This is the date given for the establishment (seitei ����) of the Family Register Law in the Dajō ruiten version of Proclamation 170 shown to the right. 1871 KosekihōDajō ruiten imagesThe inability of a government to account for all individuals subject to its authority signifies ineffectiveness -- i.e., a failure of the government's authority to reach and affect the individuals. The government cannot protect, police, or tax, conscript for labor or military service, or protect, educate, or otherwise serve, people it does not know about. The last of the notices concerning restoration to registers (fukuseki ����) of people who have left or been omitted from registers (dasseki-sha �E�Ў�) is of interest in that it refers to the general register as an "[affiliated] population register" (minseki ����). The notice reports that a certian "shizoku" (�m��) or "(lower-ranking) (former) samurai" or "gentry" who left his [shizoku] register lowered to "shomin" (����) or "commoner" status and enrolled in a "minseki". The "shizoku" caste was created by Great Council of State (Dajōkan ������) Proclamation No. 576 of Meiji 2-6-25 (1869-8-2). The 1871 Family Register Law recognized "shizoku" as a register status, but the status had no privileges. The recording of "shizoku" as a register status in new registers ended with with 1914 revisions in the Family Register Law effective from 1915. And 1947 revisions effective from 1948 provided that "shizoku" be struck from active registers. "Shizoku" register leaver registered as "shomin"Settled people are more easily registered or counted by registrars and census takers than itinerants and migrants.

�������m�����R�c���Z�E�Ѓj�t���l�j���V���Ѓj�ғ� |

||||||||

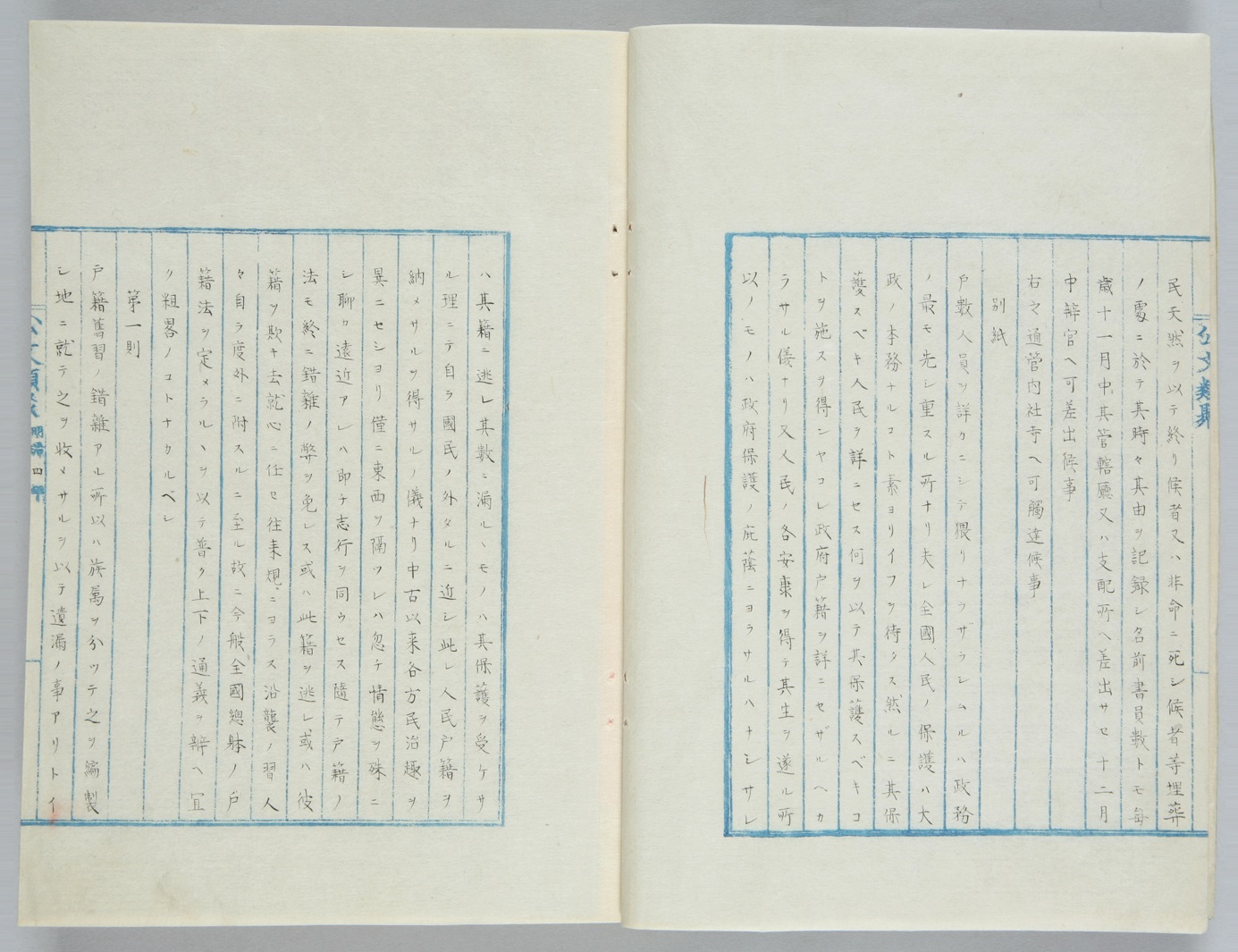

Preamble to 1872 Family Register Law

The preamble to the 1872 Family Register Law is a remarkable statement. Japan's family registration system is often associated with social control. However, the preamble shows the importance given to domicile registration, both as a means of social control, and as a way to insure that subjects were able to benefit from the services of their government.

The Family Register Law continues to be, in many ways, the "law of land" -- upon which rest the principles of family law set down later in the Civil Code and reflected in the Nationality Law.

The following tables show transcriptions of both the 1871 preamble and a 1900 English translation, followed by my own partial structural translation, then commentary.

|

Preamble to 1871 Family Register Law (Dajokan Proclamation 170) Requiring local governments to register affiliated residents and compile and report demographic statistics to national government |

|||

Sources

Japanese textsTop text My (Yosha Bunko) transcription of the Dajō ruiten scan from National Archives Digital Archive. The received text is totally unpunctuated, in accordance with the convention of writing at the time, and voicing was not marked. I have added �B (periods) after terminal conjugations. I have also inserted �R�g (koto) where it was abbreviated with a mark which looks like �� in the received text. Bottom text This text is a straight copy-and-paste from a transcription provided by Shibusawa Eiichi Memorial Foundation (�a��h��L�O���c), Digital edition "Shibusawa Eiichi historical materials" (�f�W�^���Łw�a��h��`�L�����x). This version (1) does not show the title "Besshi" (�ʎ�), (2) uses present-day kanji, (3) preserves the katakana usage of the original text, but (4) adds "koto" (�R�g) where it was abbreviated with a mark which looks like "��", and (5) marks junctures with commas (�A). English translationsThe 1904 English translation is my transcription from the 1904 yearbook. The structural translation, which endeavors to cut as close as possible to the phrasal and metaphorical bone of the original, is mine. I have shown both a polished version, and a version which leaves all the construction marks. Highlighting and commentaryI have highlighted selected terms to faciliate their discussion. |

|||

|

1871 Japanese text |

1904 English translation |

||

Yosha Bunko transcription of Dajō ruiten scan�ʎ� �˝ɐl�����ڃj�V�e���i���T���V�����n�����m�Ń���V�d�X�����i���B �v���S���l���m�ی��n�吭�m�{���i���R�g�f�����]�t���҃^�X�B �R���j���ی�X�w�L�l�����ڃj�Z�X�����ȃe���ی�X�w�L�R�g ���{�X���������B�������{�ː����ڃj�Z�T���w�J���T���V�i���B ���l���m�e���N�����e�������������ȃm���m�n���{�ی�m�݈��j�����T���n�i�V�B�����n�������������Ƀj�R���R���m�n���ی샒��P�T�����j�e���������m�O�^���j�߃V�B �����l���ː����[���T�������T���m�V�i���B�sBreak in English�t���ÈȘҊe��������كj�Z�V�����̓j�������u�c���n���`��ԃ���j�V�փJ���߃A���n�u�s�����t�Z�X笃e�ː��m�@���I�j���G�m�����ƃ��X�B ���n�������������n�������\�L���A�S�j�C�Z���ҋK�j�����X�B ���P�m�K�l�X�����x�O�j���X���j�����B �̃j���ʑS���`铃m�ːЖ@���胁�����R���ȃe���N�㉺�m�ʋ`�����w�X�V�N�e���m�R�g�i�J���w�V�B Shibusawa transcription�ː��l�����ڃj�V�e���i���T���V�����n�A�����m�Ń���V�d�X�����i���A�v���S���l���m�ی�n�吭�m�{���i���R�g�f�����]�t���҃^�X�R���j���ی�X�w�L�l�����ڃj�Z�X�A�����ȃe���ی�X�w�L�R�g���{�X���������A�������{�ːЃ��ڃj�Z�T���w�J���T���V�i���A���l���m�e���N�����e�������������ȃm���m�n�A���{�ی�m�݈��j�����T���n�i�V�A�����n���Ѓ������A�����j�R���R���m�n���ی샒��P�T�����j�e�A���������m�O�^���j�߃V�A�����l���ːЃ��[���T�������T���m�V�i���A�sBreak in English�t���Èȗ��e��������كj�Z�V�����̓j�������u�c���n���`��ԃ���j�V�A�փJ���߃A���n���`�u�s�����t�Z�X�A���e�ːЃm�@���I�j���G�m�����ƃ��X�A���n���Ѓ������A���n�ސЃ��\�L�A���A�S�j�C�Z�A�����K�j�����X�A���P�m�K�l�X�����x�O�j���X���j�����A�̃j���ʑS�����̃m�ːЖ@���胁�����R���ȃe�A���N�㉺�m�ʋ`���كw�A�X�V�N�e���m�R�g�i�J���w�V |

1904 yearbook representation[ Prologue ] It is the utmost importance in the administration affairs of a country (����) to keep accurate account of the number of its families and individuals (�˝ɐl��), for, unless this number is accurately known, the state (�吭) can hardly attend to its primary duty (�{��) of extending protection to its subjects (�S���l���m�ی�). The subjects (�l��) will also, on their part, enjoy peace and prosperity and can pursue their business unmolested only when they are under the protection of their government, so that should it ever happen that their domicile is absent from the official record, owing either to their own negligence or evasion or from an oversight on the part of the government officials, those people will be practically non-existent in the eyes of the government and will therefore be excluded from the enjoyment of the protection universally extended by the government to its people. Lack of uniformity in the local administration from about the time of the Middle Ages has, among other irregularities for which it is accountable, reduced the business of keeping personal register [sic = registers] to a state of disorder; people were allowed to remove their abodes without giving notice to the authorities, and even to evade with impunity the duty of registering themselves in the census record. Accustomed for ages to these irregular practices, people are prone to regard the duty of registration with perfect indifference. It was in view of this circumstance that the rules of keeping census records throughout the country have now been provided, and that the local authorities and the people are hereby enjoined to duly regard the points herein set forth and to carefully attend to them. Yosha Bunko translation (polished)Ascertaining the count of households and the number of people, and not allowing the figures to be disorderly, is the most important aspect of Government work. Needless to say the primary work of the Government is the protection of all the people in the country. If the Government does not ascertain the people it is to protect, how can it perform its work of protection? . . . To be continued. |

||

Structural translation (Yosha Bunko)Clarifying [ascertaining] the count of households (�˝�) and the number of persons (�l��) and not allowing [these figures] to be disorderly [corrupt] is [the] most prior and weighty [== first and most important] place [part, aspect] of government work (����). That the protection of the people of the entire country (�S���l���m�ی�) is the primary work of the Great [Imperial] Government [of Japan] (�吭�m�{��) from the start does not wait to be said [== of course does not need to be said] [== Needless to say the primary work of the Government is the protection of all the people in the country]. �R���j���ی�X�w�L�l�����ڃj�Z�X�����ȃe���ی�X�w�L�R�g���{�X���������B Whereas by not clarifying the people who [it = the government] is to do this protection, with what [how] can [it] not not perform the doing of this protection? [== If the government does not ascertain the people who it is to protect, how can it perform its work of protection?] To be continued. |

|||

Notes and commentaryQuality of 1904 translationReaders of both the 1871 Japanese and 1904 English texts will observe that the English version, published over a century ago as of this writing, reflects the spirit of the Japanese version -- but also manifests the common practice then (and at times even today) to inflate and embellish lean, lucid, well constructed Japanese phrases -- in the interest of placating a god shelf laden with verbose and even pompous English deities. Note that none of the keywords or phrases in the original text are accurately reflected in the 1904 English version.

Keywords�ː� Village population records were generally linked with land records. People who had settled in a village resided in a dwelling located on land associated with the village. And it made administrative sense to treat the land and the dwelling as the unit for counting heads as well as recording personal information that allowed authorities to determine tax and labor obligations. Thus registers (seki ��) generally recorded people who resided in the same dwelling as a household or family. The term "kokō" (��?) was used to signify both the number of dwellings (doors �� to) and population (mouths �� kuchi) of a village. "Household" is probably the more accurate English dub for "ko" (��) than "family", because the inhabitants of a dwelling might include people who were not members of the biological or corporate family, but were live-in servants or employees, or boarders (lodgers), or even mistresses. �S���l���m�ی� The writers of the preamble of Japan's first population registration law understood that the primary rationale for the existence of any state is the protection of its people. A state incapable of protecting its people is practically by definition not a state. A state that delegates its foreign affairs and defense to another state becomes a dependency of the other state, and ceases to be a state in its own right. Here, of course, we are talking about "protection" in the form of administration of governmental policies related to the social organization and lives of the people, as well as policies related to the rights and duties of subjecthood. �l�� The term "jinmin" was not widely used in later Japanese laws to refer to the people of Japan either collectively or individually. Later it was used -- and today it continues to be used -- mainly in treaties between Japan and another country, in which reference is made to "the people" or "a person" of Japan or the other country. In other words, it came to be used as a "generic" term in "international" contexts in which it was necessary to conflate terms in domestic laws like "subject" (�b�� shinmin) and "national" (���� kokumin) or "citizen" (���� kōmin, �s�� shimin). In the 1876 Kanghwa treaty between Japan and Chosen, the official Japanese and Chinese versions speak of "a person of the country of Chosen" (���N���l�� Chōsen-koku jinmin) and "a person of the country of Japan" (���{���l�� Nippon-koku jinmin), whereas the unofficial English version has respectively "a subject of Chosen" and "a Japanese subject". See 1876 Kanghwa treaty between Japan and Chosen for the texts of the treaty and commentary. ���� Literally a "person" or "affiliate" of a country. This would become the most general reference in Japanese domestic laws, when referring to the people of Japan as affiliates of the state as opposed to "loyal people" or "subjects" (�b�� shinmin) of the emperor. And "national" would become the only term for the "people" of Japan after 1945, when SCAP forbade the use of "shinmin" -- the term used in the 1890 Constitution. The 1947 Constitution used "kokumin". �b�� Shinmin was introduced as term for status as an affiliate of Japan, as a state, no later than the 1871 Family Register Law. It then became the term for state affiliation in the 1890 Constitution. Though the 1899 Nationality Law was predicated on the Constitution, it spoke only of being "Nihonjin" (Japanese). Other laws spoke of "shinmin" or "kokumin" (nationals) according to the needs of the law. "Shinmin" was banned in 1945 by the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, in favor of "kokumin", which became the term for state affiliation in 1947 Constitution and in all postwar laws, including the 1950 Nationality Law, which was predicated on the 1947 Constitution. |

|||

Article 1 of 1872 Family Register Law

Subjects at large by status

Article 1 (��ꑥ) reads as follows.

��ꑥ

�ːЋ��K�m���G�A�����ȃn�A���������c�e�V���Ґ��V�A�n�j�A�e�V�������T�����ȃe�A��R�m���A���g嫃��V�������X���m�փ����T���j�˃����A�̃j���x�Ґ��m�@�A�b����ʉؑ��m�����K���m�����������]�ȉ��y�V���Z���m�n�j�A�e�V�������A�ꃉ��X�i�L���|�g�X�A�̃j�e�n���y�n�m�X�j���q�A�\����惒�胁�A����˒����j�����u�L�A�����j�����V�e������ː��l�������o�������ڃj�X�����������V���w�V

Note and source

The commas are not in the original text. They are shown here as received in the transcription provided by Shibusawa Eiichi Memorial Foundation (�a��h��L�O���c), Digital edition "Shibusawa Eiichi historical materials" (�f�W�^���Łw�a��h��`�L�����x).

The article stipulates that "subjects at large" (shinmin ippan �b�����) were to be registered under one of six statuses.

- �ؑ� kazoku "nobility", "peerage"

Higher ranking court officials and aristocrats not including members of the imperial family, and former domain lords and such, who in 1884 received titles of nobility modeled on those used in the British Empire. Titles were confered on the male heads of household and were hereditary. An adopted son also qualified as a titular heir. Titles came with legal privileges, and as a caste, title holders constitute the "peerage" from which members of the House of Peers were appointed by the emperor. All titles of nobility were forbidden by the 1947 Constitution and struck from household registers. - �m�� shizoku "gentry"

Former higher (retainer) samurai who served as administrators in domains. Received a one-time only stipend when domains were disbanded. Title brought some social status but no legal privileges. Title later invited derision as many shizoku squandered their stipend and failed in their endeavors to start buisnesses. By the early 20 century the titles were no longer being copied in new registers. After the Pacific War (1941-1945), titles remaining in registers were deleted. - �� sotsu "soldier"

Rank and file lower samurai who merely lost their jobs. All were later folded into "commoner" (heimin) status. - �K�� shikan "shinto priest"

An official who presided over a Shinto shrine or ceremonies. Later folded into "commoner" (heimin) status. - �m�� soryo "buddhist monk"

Those who had left their secular homes and devoted themselves to a Buddhist life. Later folded into "commoner" (heimin) status. - ���� heimin "commoner"

All other "subjects at large". Status abrogated in 1947, since which there have been only two statuses -- people registered in ordinary registers governed by the Family Register Law and the Civil Code -- and people in imperial family registers, pursuant to different laws. Though there have been a few female tennō in history, the present imperial family is legally a patrilineal caste. Lack of a male heir may someday force the government to revise the law to permit female succession and allow a commoner male to enter the imperial family as the husband to a princess of the blood.

Imperial family members were not "subjects at large" as they were recorded in imperial family registers. As defined by such registers, the imperial family at the end of the Pacific War (1941-1945) was a large extended caste composed of 14 princely houses (families). In May 1946, early in the Occupation of Japan, the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers abrogated economic and other privileges of the imperial family. Thus pressured to reconsider its membership, a family conference on 13 October 1947 resulted in reducing the family by 11 houses, leaving only 3 houses consisting of the male descendants of Yoshihito (Taishō) -- namely Hirohito and his siblings -- and their families. At the time of this writing (October 2020), there are 6 very small houses totalling 18 members, 13 of them women.

Article 32 of 1872 Family Register Law

Eta, hinin and such

Article 32 (��O�\��) reads as follows.

|

��O�\�� Notes and source

|

Article 32 follows articles which have described how people are to be registered, beginning with Article 1, which stipulates the 6 statuses in which people are to be classified on registers, from kazoku (nobels) to heimin (commoners). Heimin are essentionally farmers, craftsmen, and merchants -- in other words, everyone who does not qualify for one of the 5 higher statuses -- the 1st for the nobility, the 2nd and 3rd for former warriors, and the 4th and 5th for active clergy.

But the heimin status also embraces people who were lower than farmers, craftsmen, and merchants -- such as eta and hinin, who were collectively regarded as "senmin" (�˖�) -- "base" or "mean" people (outcastes) -- as opposed to "ryōmin" (�ǖ�) -- "good" or "proper" people (incastes).

By Article 32, eta, hinin and such who had been co-residing and working with or as farmers, craftsmen, or merchants would already have been registered as heimin. The problem now is how to register the itinerants and others living on the fringes of villages and other settlements, who might not have fixed addresses, or known family ties, dates of birth, or even names.

Article 32 is intended to pick up the rootless remainders, and hence begins like this.

�q����l�������g�ːЃ����t�Z�T�����m�R�@�L�n�E�E�E

The likes of an eta or hinin or such, who does not have (does not share, is not in) the same household register with a heimin [and would thus already be registered as a heimin] . . .

"Eta, nihin and such" emancipation proclamations

Other proclamations had recently provided for emancipating "eta, hinin and such" (�q����l��) from their status appellations and treating them as "heimin".

Great Council of State proclamation No. 448 of Meiji 4-8-28 (12 October 1871) provided as follows.

�q����l���V�i��p��������g���E�Ƌ��������l��

Article abolishing the appellations of eta, hinin and such: From now it shall be possible for both the statuses and occupations [of eta, hinin and such] to be [treated] the same as [those of] commoners (heimin).

Proclamation No. 449, of the same date, provided as follows.

�q����l���m�i��p�����ʖ��Ѓj�ғ��V�g���E�Ƌ��s�e����j������l�戵�ރ��n�d���O��蠲�m�d�����L�V��n�R�����V�������撲���U�Ȃ։f�o��

Article abolishing the appellations of eta, hinin and such: [Eta, hinin and such] shall be enrolled in general people's [affiliated population] registers (ippan minseki ��ʖ���). It shall be possible to treat both [their] statuses and occupations entirely the same [as others in such registers]. However, because there is the convention of exemption from land taxes et cetera [for those who have been regarded as eta, hinin and such], the Treasury Ministry will be asked to examine the prospects of how to revise [this convention].

These proclamations were issued nearly 5 months after the promulgation of the Family Register Law by Proclamation No. 170 of of Meiji 4-4-4 (22 May 1871), and nearly 4 months before its enforcement from Meiji 5-2-1 (9 March 1872).

1872 Jinshin register statistics

Households by sex of heads, and persons by sex, by status

The following data were adopted from kosekinorekisi (�ːЂ̗��j) [history of koseki]. ← Website no longer exists

The table design, translated headings, and comments are mine.

Similar data, with slightly different headings, and many other tables of early Meiji family register statistics broken down by status and sex, and prefecture, are now posted on Wikipedia's �p�\�ː� (Jinshin koseki) page.

These data dramatize the variety of status categories used to classify people who were subject to registration under the 1871 Family Register Law proclamation effective in 1872.

|

�p�\�ː� ����5�N1��29�����݂̒��� |

Jinshin [1872] household registers Survey as of 8 March 1872 |

||||||

| �g�� | �ˎ�j | �ˎ受 | �ː� | �j | �� | �l���� | ���v |

| Household heads by sex | Households | People by sex | People | Prcnt of | |||

| Status | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | Total |

| Imperial family�c�� | 7 | 4 | 11 | 14 | 15 | 29 | 0.0001 |

| Nobility �ؑ� | 459 | 0 | 459 | 1,300 | 1,366 | 2,666 | 0.0081 |

| Gentry (former) samurai �m�� | 258,939 | 13 | 258,952 | 634,701 | 647,466 | 1,282,167 | 3.87 |

| Soldier (former) samurai �� | 166,873 | 2 | 166,875 | 334,407 | 324,667 | 659,074 | 1.99 |

| Landed (former) samurai �n�m | 646 | 0 | 646 | 1,715 | 1,601 | 3,316 | 0.0100 |

| Monks �m | 75,925 | 0 | 75,925 | 151,677 | 60,169 | 211,846 | 0.64 |

| Shinto priests ���_�� | 20,895 | 4 | 320,938 | 52,141 | 50,336 | 102,477 | 0.31 |

| Nuns �� | - | 6,068 | 6,068 | 0 | 9,621 | 9,621 | 0.0290 |

| Commoners ���� | 6,326,571 | 170,752 | 6,497,323 | 15,619,048 | 15,218,223 | 30,837,271 | 93.13 |

| Karafutoans �����l�� | - | - | - | 1,155 | 1,203 | 2,358 | 0.0071 |

| Total �v | 6,850,315 | 176,882 | 7,027,197 | 16,796,158 | 16,314,667 | 33,110,825 | 100.00 |

See The Interior: The legal cornerstone of the Empire of Japan for an overview of status and other laws in Japan's prefectural Interior from the 1872 Family Register Law to the present. |

|||||||

Meiji-era household registration handbooksFor officials and other family law facilitatorsAs I write this in 2021, about 124 million people in the world are Japanese. By this I mean they possess Japan's nationality -- an artifact of having a primary domicile register (honseki �{��) affiliated with a municipality in Japan. This writer has such a register, and therefore I am Japanese. It's that simple. But not so simple for municipal registrars, who are busy creating new registers for everyone who is recognized as Japanese at time of birth or later in life, and confirms the identities of their parents, and keeps track of all vital events in the person's life -- marriage, births or adoptions of children, divorce, changes of name or primary address, closing the register when one dies, or before one dies if one becomes an alien. The registers are called "honseki" or "primary registers" when referring to their function as signifying that a person belongs to the locality designated on the register -- the municipality having juisdiction over the address on the register -- and belongs, in turn, to the prefecture having jurisdiction over the village, town, city, or ward -- and belongs, again in turn, to the country or state -- in this case Japan -- having jurisdiction over the prefecture. Japan attributes its nationality only to people in registers affiliated with local polities within its sovereign dominion. This makes its nationality not only territorial but derivative of local territoriality. To put it somewhat differently -- territorial affiliations are nested. I am not Japanese because my register is affiliated with Japan. I am Japanese because my register is affiliated with a local territory that is affiliated with provincial territory that is affiliated with Japan. So Japanese nationality is about locality -- or, more precisely, about being duly registered as belonging to a locality that belongs to Japan. Japan's Nationality Law does not make such stipulations because the equation of nationality with municipal (local) registration is taken for granted. The purpose of the 1871 Family Register Law was to account for the people (jinmin), nationals (kokumin), and subjects (shinmin) of Japan defined as the aggregate of its local communities, broken down and numbered to facilitate the initial registration in 1872. The inhabitants of new territories became Japanese through the agency of acession, and inhabitants of lost territories ceased being Japanese through the agency of secession. The territorial imperative of Japan's nationality is clearly seen in the manner in which people gained Japan's nationality during the years of territorial expansion prior to the Pacific War, and lost Japan's nationality as a result of postwar territorial reductions. Japan's Ministry of Justice legalists are not in the habit of reducing Japan's nationality to a matter of territorial affiliation. Yet nothing casts the territorial imperative of Japan's nationality in sharper relief than Civil Affairs A No. 438, the notification issued on 19 April 1952 by the Director-General, Civil Affairs Bureau, Attorney General's Office, concerning the disposition of Japanese nationality upon the effectuation of territorial terms of the San Francisco Peace Treaty on 28 April 1952. The notification reported that, upon the separation of Chōsen and Taiwan from Japanese territory, Chosenese and Taiwanese would be separated from Japanese nationality. That was, in effect, a reversal of the attribution of Japanese nationality to people in Taiwan registers and Chōsen registers when Japan gained territories it called Taiwan and Chōsen in 1895 and 1910. In a nutshell, then, Japanese nationality is primarily an artifact of territory affiliation. It has been acquired at time of birth mainly through family ties (blood) but in some cases through place of birth, and it is acquried later in life through naturalization. Until 1950, nationality later in life could also be acquired through marriage or adoption. Honseki registers are physically known as "household registers" or "family registers" (koseki �ː�), on account of their more basic function as records of formal family ties. Registers today may include only 1 person, as in my case and my son's case, or several individuals, as in my daughter's case. I am "Wezarooru", my son in "Sugiyama", and my daughter and her husband, and their daughter and son, are "Kasubushi" -- reflecting the rule that members who share a register must (1) be related through birth, marriage, or adoption, and (2) must share the same family name and register address. Whether people who share a register actually reside together, or whether anyone in the register actually resides at the address on the register, is another matter, as all Japanese who reside in Japan have, in addition to a family register, a residential registration status, which governs their political rights, tax obligations, and all manner of social services that are administered through local governments. The double-tier of legal existence in Japan as a Japanese -- the possession of a family register, and a residence at an address other than the address on the register -- doesn't double the work for registrars, but it does add to the list of things which people in Japan need to do in order to comply with laws and regulations concerning their legal existence -- which, for most, begins with registration within 14 days of their birth. From this point, every change of status -- becoming an adoptee, an alliance of marriage, becoming a biological or adoptive parent, a divorce or dissolution of an adoption, and finally death -- and every reportable change of address between birth and death -- become family register matters -- work for the people concerned, the clerks and registrars at municipal halls, and the scriveners and attorneys who may at times be called upon to help prepare notifications and other documents in difficult cases. All the above creates a huge market for legal information about registration laws and regulations, and the bureaucratic forms that need to be completed and filed, sometimes with supporting documents, at times with formal family court permissions. Japan's honseki population (�{�Аl��) as of Meiji 5-1-29 (8 March 1872) was 33,110,796. By Meiji 27-12-31 (31 December 1895) it was 42,270,620. Counts and estimates of resident populations were slightly but not very different. |

Aoki and Takasaki 1877Family registration for (literate) dummiesThis very detailed handbook, printed with copper plates in 1877, in a small book (shōhon ���{) edition measuring 11.0 x 15.0 centimeters, with 100 numbered folios (200 pages) in a conventional 4-hole folio binding. �؉� �{ Aoki Okashi (vetter) Title pageThe title page, pasted to the back of the front cover, attributes the publication to "Aoki Okashi" as the "checker" or "vetter" (etsu �{) and Takasaki Shūsuke as the "compiler" (hen ��). The title page also states that the "right-to-publish permit" (hanken menkyo �Ō��Ƌ�) was issued in June 1877, and the "owner of the blocks/plates" (zōhan ����) was "Haruka Bookshop" (Haruka Shooku �t������). Facing the title page, on what amounts to the front free fly page, is Haruka Shooku's block/plate-right's seal. Aoki Okashi (1825-1881 �؉�) was also known as Aoki Judō (�؎���) among several other names he used as a student of Chinese texts, a poet, and a government official. He was born in Nagoya and grew up in the service of Owari domain (Owari-han ������), which is now the western part of Aichi prefecture. He studied and worked in other parts of Japan during the years before and after the arrival of Commodore Perry in 1853 and the start of the Meiji Restoration in 1868. From about 1870 to 1872, he was posted to Karafuto (����), which Japan then claimed but soon traded to Russia for the northern Chishima islands (see 1875 Treaty of St. Petersburg). From 1875 and until his death in 1881 -- hence during the time he vetted Takasaki Sensuke's publication -- Aoki worked in the Treasury Ministry (Ōkurashō �呠��) in Tokyo. During his life, he compiled and edited a number of other works, some of them also published by Yūzandō Kanae. Takasaki Shūsuke (����Џ�) remains unknown to me at the time of this writing (2021). Aoki's prefaceThe 1-folio (2-page) preface, dated Meiji 10-07 (July 1877), is signed "Judō Sanjin Aoki Okashi" (�����U�l�؉�) as the "editor" (sen ��) and sealed "Judō" (����). It's Japanized Chinese (kanbun ����) text begins as as follows.

�ːЖ@�A�l�������v����A�}�� To be continued. ForewordThe 2-folio (4-page) foreward (reigon �ጾ) was "written by the compiler" (�ҎҎ�) and dated July 1877. It describes the purpose of the book and explains its notations in the manner of a legend. Takasaki's introductionThe 4-page introduction, by editor Takasaki Shūsuke, is titled "Synopsis of compilation" (Henshū no taii �ҏS�̑��). It reiterates the purpose of the Family Register Law, much as was stated in its prologue -- namely, in order to provide for the safety and wellbeing of "people throughout the country" (zenkoku jinmin �S���l��) -- everyone who belonged to the imperial state, the "emperor's country" (kōkoku �c��) -- the people (jinmin �l��), all nationals (kokumin ����) -- had to be enumerated and accounted for in "peoples household registers" (jinmin koseki �l���ː�). ColophonThe colophon says the compiler and publisher was Takasaki Sensuke of Tokyo, while the "printing bookshop" (hatsuda shoshi ���[����) agents were Nakamura Kumajirō, a hanmoto printer, and Yūzandō Kanae, a bookshop proprietor. Order of members in the same register

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Five degrees of relationship in 1871 Shinritsu kōryō Wife and concubines share same status as second degree relatives |

|||

|

�V���j�� |

Outline of new codes |

3rd-5th degree relatives omitted |

|

|

�ꓙ�e |

1st degree relatives |

�e |

2nd degree relatives |

|

���� |

Father, mother (Note 1) |

�c���� |

Grandfather, grandmother |

|

Note 1 Recognizing biological father, and biological mother as father's principal wife. Note 2 Non-biological parents. |

Note 1 As a woman, other than father's principal wife, and other than adoptive mother, to whom one was born out of wedlock, but who has been recognized by father. Note 2 As father's principal wife who is not biological mother or adoptive mother. Note 3 Parenthetic gloss gives reading of characters as "wo / dziwoba" -- i.e., "oji / oba" -- meaning "uncle / aunt" but possibly referring only to father's siblings. Note 4 Parenthetic gloss translates "Children of older and younger brothers" hence apparently these are only fraternal nephews and nieces. |

||

Wife, mistress

Arai and Takasaki mentioned mistresses but did not directly integrate them into the list of family members in the order they were to be shown in a household register (see above). However, they list "mistress" after "wife" in the 5 degree kinship chart.

The 1871 Shinritsu kōryō classifies a "wife" and a "mistress" side by side as 2nd-degree relatives in the 5 degree kinship scheme. Whether the wife or mistress had more privileges or pulled more weight in the family is another matter. The children of a mistress generally had less if any claim to inheritance -- and the unequal treatment of out-of-wedlock children today continues to be a contentious issue in family law litigation. When it came to succession, however, the son of a mistress might be groomed to be the next head of household, or a daughter of a mistress might be groomed to be the wife of an adopted son -- if the wife had no children, or if none of her children were willing or able to succeed to the headship.

Mekake were not a subject of the 1880 Penal Code enforced from 1882. And the 1898 Family Register law provided that "mekake" was no longer a valid status.

See Wives and mistresses in the "Social status laws in Japan" article for details.

Matsuura 1877���Y�G�Ҏ[ (�\���A��) Matsuura Hiroshi compiler (cover, title page) This book is small enough to fit in the sleeve of a kimono or a garment pocket. It measures 8cm wide, 17cm tall, and 1cm thick and is manufactured as a "folding book" (orihon �ܖ{). Some 66 pages were printed on one side of several sheets of paper that were spliced together to make a single long sheet. The long sheet was then folded accordian style to make 33 folios (chō ��) 30 of which -- the main text of the booklet -- are numbered. The backs of the two end pages were then pasted to semi-hard paper boards as shown in the images to the right. The contents are organized into independent upper and lower bands, which are separately described in upper and lower bands of the "mokuroku" (�ژ^) or "contents". The part on "Marriage with foreigner" (Gaikokujin to kekkon �O���l�g����), for example, spans the lower band of 2 pages (see image). The cover, title, and colophon attribute Matsuura somewhat differently -- "henshū" (�ҏW) and "henshū" (�ҏW), both meaning "compiler" -- and "henshū oyobi shuppanjin" (�ҏW�y�o�Ől), meaning "compiler and publisher". ColophonThe colophon identifies the compiler, Matsuura Hiroshi (���Y��), as a "commoner" (heimin ����) residing at 16-banchi in 2-chome of Matsuzaka-chō (���⒬) in the Honjo (�{��) quarter of the 6th minor-ward (����) in the 6th major-ward (���) of Tōkyō-fu (�����{). Tokyo was one of 10 urban prefectures (fu �{) in Japan at the time. The major-minor-ward (dai-shō ku �召��) system was created throughout Japan in 1871 to accommodate the creation of household registers. Tokyo had 97 minor wards divided into 6 major wards. This administration system was replaced in 1878 by the county-ward-town-village (gun-ku-chō-son �S�撬��) system, under which Tokyo prefecture had 15 wards with names rather than numbers. The neighborhood of Matsuura's residence is in the Ryōgoku (����) area of today's Sumida ward (�n�c��). The colophon also states that the handbook was approved by officials (monkan ����) on 21 March 1877 -- whereas the title page states that the booklet was published by the copper-plate department of Matsuura's publishing company in September 1877. Catalog of other publications in backThe last 2 folios consist of a catalog of other publications by Matsuura. It was common then, and still common today, for a publisher to advertise other titles in the back of a book. The titles publicized in this booklet were printed and sold by a bookshop (hatsuda shoren ���[����) in front of Shibadai Jinja (�ő��_�{). There is a shrine by this name in the Shibadaimon (�ő��) neighborhood of today's Minato ward. The bookshop was owned by and possibly also named Yamanaka Ichibee (�R���s���q). Presumably Matsuura produced the copper plates used to print the booklet, which Yamamoto Ichibee printed and distributed as Matsuura's agent. Yamamoto appears to have been a woodblock publisher (hanmoto �Ō�) who produced all manner of printed matter using conventional methods while adopting newer copperplate, lithograph, and metal-type technologies. Marriage with foreignersMarriages between Japanese and foreigners, while legally permitted, were rare, and of all the legal matters that might involve a Japanese at the time, the the topic of marriage with a foreigner was probably the least. Everyone was affected someway by family registration, and even matters involving, say, slaughter houses or archery ranges would have been more relevant to the daily lives of the people than a marriage between a Japanese and a foreigner who didn't have the common sense to marry their own kind. Yet contemporary household registration handbooks and other guides to civil matter s would not be complete without some reference to the 1873 proclamation that facilitated marriages with foreigners. It was, after all, a brick in the wall of family law. "Marriage with foreigners" is listed as a distinct topic on the title page and on the contents pages. As shown in the image to the right, about half a page is given to the subject. The handbook cites the 1873 proclamation on alliances of marriage and adoption with foreigners verbatim with furigana. Compare the text in the images to the right with the text shown and translated in 1873 intermarriage proclamation: Family law and "the standing of being Japanese" under "Nationality" on this website. Only the proclamation is shown. There are no remarks about procedures and forms, and no examples of cases to show how the proclamation applies., in the form of queries and replieshow the rules question and answers of the kind Note on the text to the right of "Marriage to foreigner" text on the image to the right. This is part of the "Receiving [queries about] widows in families" section, which is partly translated under "haigū (�z��) spouse". Title pageThe title page lists the following matters addressed by the handbook. Practically all are familiar to family registration public officials and private facilitators today. Keep in mind that these are topics of interest at the time the booklet was approved in March and published in September 1877 -- during the Seinan War (Seinan Sensō ����푈), sometimes called the Satsuma Rebellion, though the war came in the wake of numerous early skirmishes elsewhere, and embroiled more than Satsuma (see Seinan war on the "News Nishikie" website). The comments in the following table should not be taken as definitive. The topics are all more complicated than may seem. The laws were evolving and their enforcement varied. Some registration practices significantly changed or were discontinued over the next few decades. The most fundamental practices remain familiar today although bureaucratic procedures have changed with technology. The most important change, however, was the shifting the nationality overseeing of family registers, which are administered by municipal governments, from the Interior Ministry to the who now have jurisdiction over household registers and resident registration within their jurisdictions.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

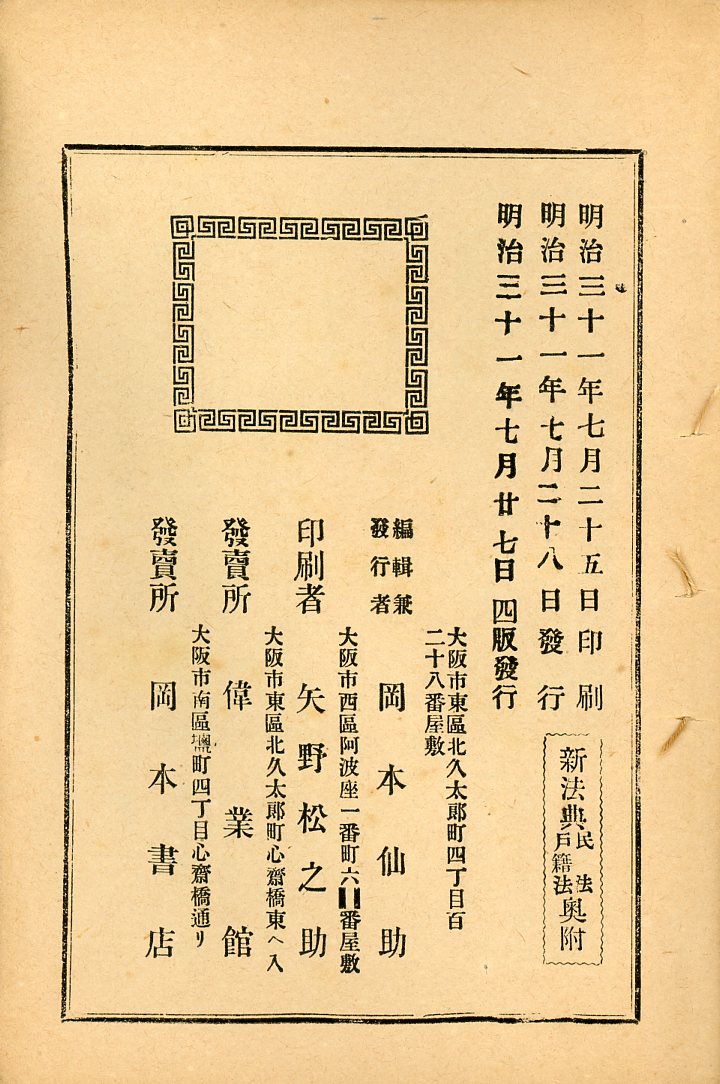

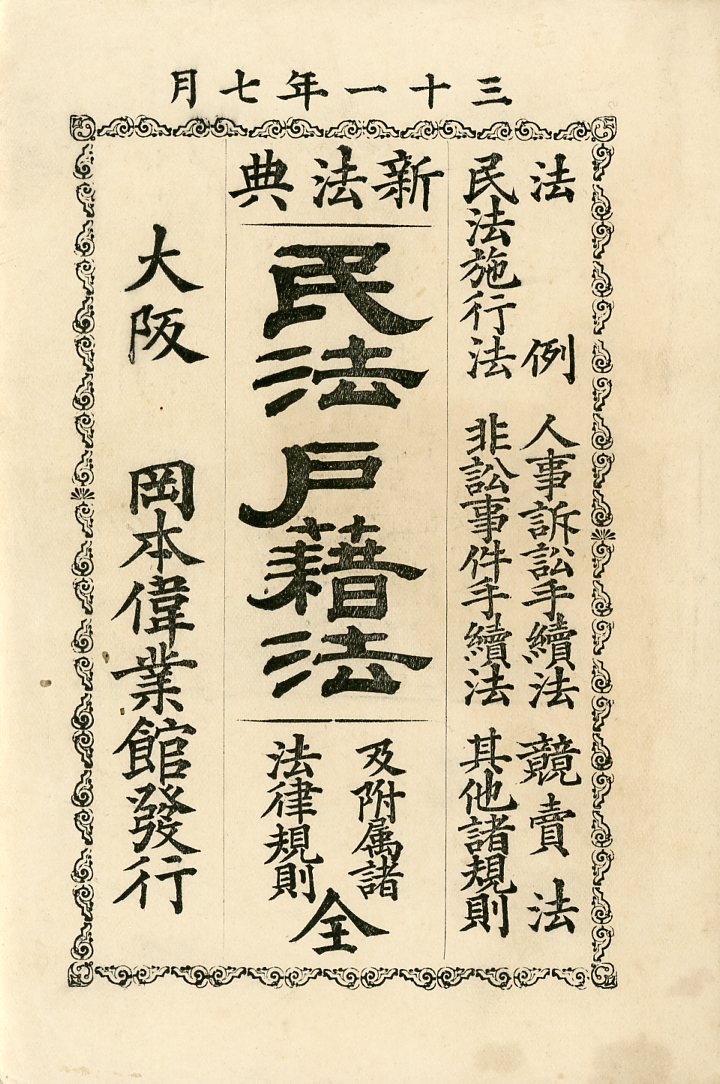

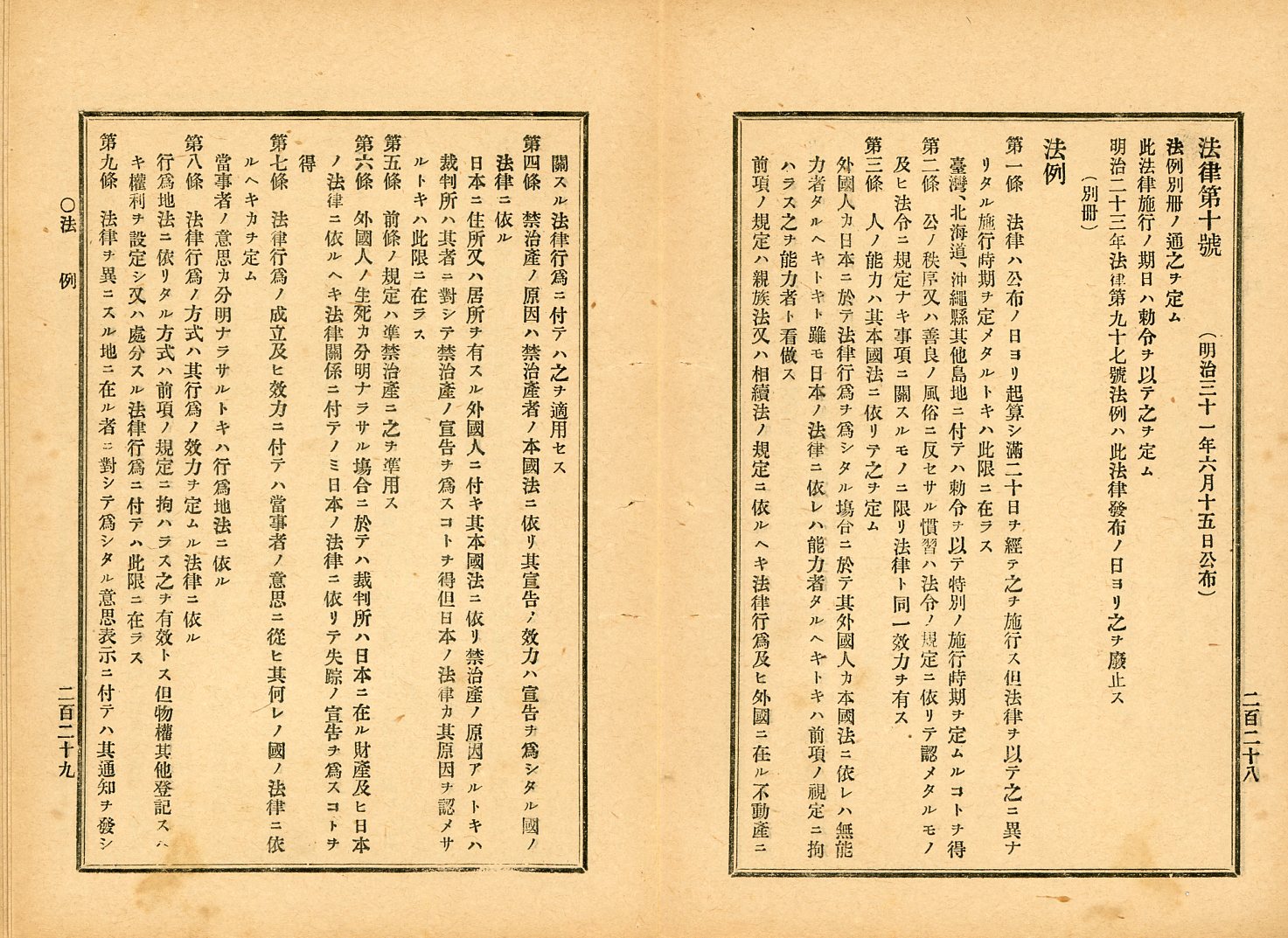

Okamoto 1898���{�叕 Okamoto Sensuke CoverThe cover highlights the following laws. Main titles (middle)

New law guide �V�@�T Other titles (right)

Rules of Law �@�� While some of the laws originated before 1898, most were revised and promulgated in conjunction with their collective enforcement in a promulgated on 21 June 1888 -- nearly a year before the promulgation and enforcement of the Nationality Law on 16 March and 1 April 1899. However, provisions were made in the new 1898 Family Register Law for procedures related to acquisition and loss of nationality pursuant to especially the 1873 proclamation on alliances of marriage and adoption with foreigners, which was revised by a law promulgated on 9 July 1898 (see 1873 intermarriage proclamation for details). The every important Rules of Laws (Hōrei �@��), first promulgated in 1890, was revamped as a new law in 1898 with nationality (kokuseki ����) stipulations (see Status and applicable law for details). |

||||||||||

Mori and Endo 1898 |

||||||||||

Endo 1898�������� �� Endō Toshizō (compiler) |

||||||||||