Separation and choice

Between a legal rock and a political hard place

By William Wetherall

First posted 1 August 2006

Last updated 21 January 2022

Prelude to nationality dispositions

Sebald's 15 August 1949 "Status of Koreans in Japan" dispatch

1950 Nationality Law

Callanan's 20 September 1950 transmittal to DOS

•

Hiraga's 1 June 1950 overview of 1950 Nationality Law

•

Hiraga 1950-1951 statements on "Chosenese and Taiwanese"

1952 Civil Affairs A No. 438 notification

The effects of territorial separations on nationality and registers

Expedited naturalizations

How Japan helped Chosenese and Taiwanese civil servants remain Japanese

Legacy aliens get permanent residence

How Japan treated nationality losers and long-term residents

Beware of what you wish for

Nationality recovery and choice -- of what, for whom, where, and with what obligations?

Rejected choice conventions

10 Sep 1919 Allied Powers and Czecho-slovakia

•

10 Sep 1919 Allied Powers and Austria

Laterality

Mitchell 1967

•

Changsoo Lee 1971 & 1981

•

Hicks 1997

•

Weiner 1997

•

Koshiro 1999

•

Fukuoka 2000

•

Kashiwazaki 2000

•

Ryang 2000

•

Yoneyama 2000

•

Takemae 2002

•

Ishikida 2005

•

Soo im Lee 2006

•

Wetherall 2006

•

Morris-Suzuki 2007

•

Chapman 2008a

•

Weiner & Chapman 2009

•

Chung 2010

•

Jones 2014

Race and nationality

Chung 2010

•

Dower 1999

Related article

Postwar nationality: Japan's bilateral talks with ROC and ROK

Prelude to nationality dispositions

The official position of the Allied Powers toward the legal statuses of Koreans (Chosenese) and Formosans (Taiwanese) in Occupied Japan -- as reflected through policies established under the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP) -- was essentially that Koreans and Formosans would be "non-Japanese" for purposes of repatriation and registration, but would remain Japanese -- i.e., Japanese nationals, people with Japanese nationality -- until they voluntarily returned to Korea or Formosa, or migrated to another nationality through legal procedures governed by a recognized diplomatic mission in Japan.

The status of Taiwanese in Japan

The terms of surrender, signed on 2 September 1945, embraced the 1945 Potsdam Declaration, which embraced the 1943 Cairo Declaration, which stipulated that "all the territories Japan has stolen from the Chinese, such as Manchuria, Formosa, and the Pescadores, shall be restored to the Republic of China." ROC, as one of the major Allied Powers in the war against Japan, received Japan's surrender of Taiwan and the Pescadores (hereafter "Taiwan") on 25 October 1945, and immediately began to integrate the territory as a province of China.

On 22 June 1946, the Executive Yuan restored Chinese nationality, retroactive to 25 October 1945, to all "overseas Taiwanese" -- meaning people with Taiwan registers wherever they might be residing outside Taiwan. The measure gave such Taiwanese until the end of the year to notify an ROC mission or representative of their wishes.

ROC, as an Allied Power, had a mission in Occupied Japan, where roughly 20,000 ROC nationals were residing. These were mostly Chinese who had settled in Japan before the war, some as long ago as the late 19th century. As ROC nationals, they were treated as United Nations nationals -- a virtual extraterritorial status in Occupied Japan which qualified them for food and other rations, and in some cases protection from Japanese courts.

SCAP of course permitted ROC's mission to enroll Taiwanese into its nationality. Thus most Taiwanese in Occupied Japan became Chinese, which qualified them as United Nations nationals -- referring to nationals of the Allied states that declared war on Japan on 1 January 1942.

When migrating to ROC nationality, Taiwanese in Japan relinquished their Japanese nationality. Whether they did so verbally is not clear. In effect, however, they began to be treated as ROC nationals.

While the language of the Cairo Declaration was strong, ROC recognized that Japan had legally acquired Taiwan in 1895 under the terms of the Shimonoseki Treaty, which provided that Taiwanese stood to be become subjects of Japan. And SCAP anticipated that ROC, as an Allied Power, would be party to a peace treaty with Japan, in which Japan would formally retrocede Taiwan to China and agree to mutually acceptable nationality settlements.

However, by 1951, when the Allied Powers and Japan began to negotiate a peace treaty, a new Chinese state -- the People's Republic of China (PRC) -- had been established on the mainland of China, and ROC had been driven into exile on Taiwan. Moreover, the Allied Powers were divided in their "China" recognition. Consequently, the San Francisco Peace Treaty provided only that Japan "renounces (放棄する hōki suru) all right, title and claim to Formosa and the Pescadores" (Article 2 (b)). The treaty did not designate a successor state or make provisions for nationality settlements.

Though practically all Taiwanese had already become ROC nationals, under in the eyes of Japanese law they would not formally lose Japan's nationality until 28 April 1952, when the terms of the Peace Treaty came into effect. On the same day, though, Japan and ROC signed their own peace treaty, in which Japan recognized that "For the purposes of the present Treaty, nationals of the Republic of China shall be deemed to include all the inhabitants and former inhabitants of Taiwan (Formosa) and Penghu (the Pescadores) and their descendants who are of the Chinese nationality in accordance with the laws and regulations which have been or may hereafter be enforced by the Republic of China in Taiwan (Formosa) and Penghu (the Pescadores)" (Article 10).

In a protocol attached to the treaty, Japan recognized that "the terms of the present Treaty shall, in respect of the Republic of China, be applicable to all the territories which are now, or which may hereafter be, under the control of its Government." As Japan had already renounced all rights over Taiwan, it could cede Taiwan to ROC, which had gained control over Taiwan when it received Japan's surrender of the territory. All Japan could do was to recognize that Taiwan was under ROC's control.

The status of Koreans in Japan

Koreans (Chosenese) in Occupied Japan did not receive the same legal treatment under SCAP, which represented the legal authority of the Allied Powers to oversee treaty-accorded changes of status related to enforcing the territorial transfers stipulated in or implied by the terms of surrender. The main reason SCAP could not treat Koreans in Japan the same way is that -- in the eyes of the Allied Powers -- there had been no Korean state to occupy and govern Chōsen following Japan's surrender of this territory.

Unfortunately, the Allied Powers divided Korea (Chōsen) into two occupation zones, north and south of the 38th parallel of latitude. The northern provinces were occupied by the Soviet Union, and the southern provinces by the United States. The Republic of Korea (ROK) was established in the American zone in the south on 15 August 1948, and 6 weeks later, on 9 September, the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK) was founded in the northern Soviet zone, thus ending the formal occupations of the peninsula but leaving it divided by two states, both of which claimed to be the legitimate government the "Korea" which the Allied Powers had "liberated" from Japan. However, the two Koreas had effective control and jurisdiction only over the provinces within their borders.

The San Francisco Peace Treaty provided that "Japan, recognizing the independence of Korea, renounces all right, title, and claim to Korea, including the islands of Quelpart, Port Hamilton and Dagelet (Article 2(a)). The treaty regarded "Korea" (緒戦 Chōsen) -- as it regarded "Formosa" (台湾 Taiwan) -- as merely a territory that Japan had lost, without designating a successor state or making provisions for nationality settlements.

ROK as only successor government

By 15 August 1949 -- the date of William J. Sebald's dispatch on the "Status of Koreans in Japan" (see below) -- the United Nations, and the United States and a number of other Allied Powers, had recognized the Republic of Korea as the only legitimate Korean successor state. ROK claimed that it originated as the Provisional Government of Korea (PGK) in exile, formed in the thick of a liberation movement sparked on 1 March 1919, some 9 years after the Empire of Japan had annexed the Empire of Korea as Chōsen.

ROK also claimed that -- because PGK had declared war on Japan and contributed to the resistance against Japan -- ROK, as PGK's successor, should be recognized as an Allied Power. Apparently Sebald agreed with this, or perhaps for other reasons he proposed that ROK's Diplomatic Mission to Japan be permitted to attribute its nationality to qualified Koreans in Japan, who would then -- like Taiwanese who had migrated to ROC nationality -- qualify for treatment as United Nations nationals -- i.e., nationals of the Allied Powers.

However, SCAP's superiors in Washington, DC, balked at accepting Sebald's proposal -- and this appears to have been the main pretext for Sebald's "Status of Koreans in Japan" dispatch. As an historical document, though, the dispatch is more valuable for the manner in which it clarifies what would remain the status of Koreans legally residing in Japan for the duration of the Occupation.

Cold war developments

While Sebald was drafting the "Status of Koreans in Japan" dispatch, ROC was losing a civil war with the People's Liberation Army in China. On 1 October 1949, just 6 days after the dispatch, revolutionary communist forces in China established the People's Republic of China (PRC). And by December, remnants of the nationalist ROC government not already on Taiwan, and surviving ROC forces and a number of pro-nationalist civilians, had fled the mainland to Taiwan, and Chiang Kai-shek had declared Taipei ROC's temporary capital. Chiang would never return to the mainland, and in time Taipei would become the exiled government's permanent capital.

The United States continued to recognize ROC, which was one of the founding states of the United Nations, and one of the 5 members of the Security Council that had veto powers -- the others being France, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States. France and the United States continued to recognize ROC, but the Soviet Union (3 October 1949) and the United Kingdom (1 January 1950) recognized PRC.

ROC had been one of the "Big Four" Allied powers in the war against Japan -- with the United States and the United Kingdom from the start of the war, and with the Soviet Union by the end of the war. However, the Soviet Union and the United Kingdom opposed ROC's participation in the peace treaty, arguing that PRC should represent China. The political solution was to conclude a treaty without China -- ROC or PRC. In the end, the Soviet Union, unable to get its way in other matters, declined to join the treaty.

In the meantime, ROK and DPRK continued to vie for international recognition as the sole legitimate "Korean" state. The United States and the Soviet Union, which had divided and occupied the peninsula and backed the establishment of the two states in their respective occupation zones, continued to be divided over their "Korea" recognition as well as over their "China" recognition.

Later developments

Sebald could not have foreseen that, 10 months later, on 25 June 1950, DPRK would invade ROK, and the festering "cold war" would become a protracted "hot war". The Korean War would arouse powerful ideological fears about revolutionary communism in Japan, which would in turn affect SCAP, Japanese Government, and ROK opinion regarding how to solve the "Korean problem" in Japan. Though most Koreans in Japan were from provinces south of the 38th parallel, in ROK, it appeared that most support DPRK, north of the parallel.

As the war raged, the border between the embattled states kept shifting. Wartime "Korea" was the last place most Koreans in Japan would want to go. And ROK rivaled Japan as the last place in the world that wanted Japan's Koreans. Yet in the end, SCAP concluded that they were, indeed, "Japan's" Koreans. The communists among them may not have been welcome, but deporting them to ROK was not a political or humanistic option.

Koreans in Japan belonged in Japan, where most had been living when Japan surrendered to the Allied Powers on 2 September 1945. Most had decided to remain in Occupied Japan, partly because they heard that conditions on the divided peninsula were worse than in Japan -- but mainly, it seems, because they had settled in the prefectural Interior and brought or started their families there. By 1950, as many as half of all Koreans in Japan had been born in the prefectures, and not a few families were the result of marriages between people in peninsular registers (Chōsenjin) and people in prefecture registers (Naichijin). Though Japan may at times have been a hostile place, it was nonetheless "home" to most Koreans there.

Japan-ROK talks

The disconnect between preferred domicile in Japan, and racioethnic (national) if not also political identity with the Korean peninsula, would continue to be an emotional problem for not a few Koreans in Japan. Their legal problem, though, was that their legal status, and the rights and duties that derive from civil status, were at the mercy of Japan and ROK when it came time for them to negotiate a status agreement.

Under ordinary circumstances, the Allied Powers would have been empowered -- even obliged -- to dictate a status agreement formula based on any number of precedents in other territorial settlements. However, under the circumstances that prevailed in the late summer of 1951, when the Peace Conference was convened in San Francisco, the Allied Powers and Japan had little choice but to sign a treaty that made no provisions for settlements with "China" or "Korea" -- other than to oblige Japan to negotiate with any state that claimed to have outstanding issues.

William J. Sebald, representing what little authority SCAP had left after the signing of the San Francisco Peace Treaty, could do little more than pressure ROK and Japan to sit down at a negotiating table -- then leave them to their own diplomatic devices. The point at which SCAP could compel the two states to model their agreement on a precedent treaty had passed.

For an overview of the 1951-1952 ROK-Japan talks, see Postwar nationality: Japan's bilateral talks with ROC and ROK.

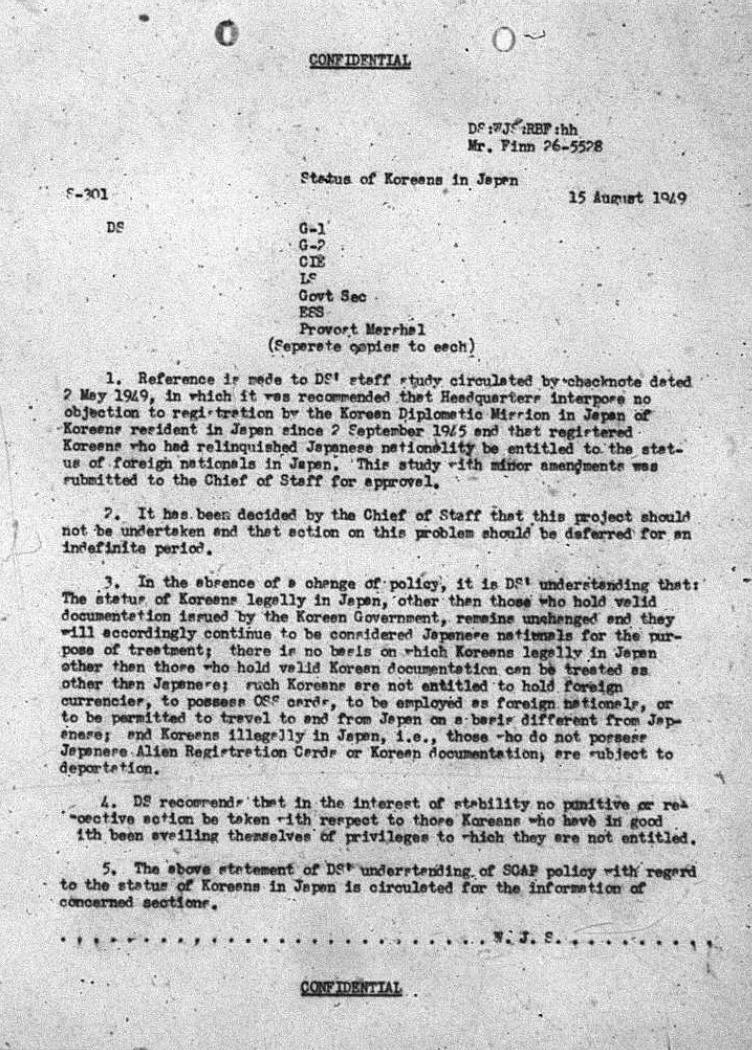

Click on image to enlarge |

Sebald's 15 August 1949 "Status of Koreans in Japan" dispatch

William J. Sebald, a bilingual attorney who had spent many years in Japan before the Pacific War, studying Japanese and translating Japanese laws, became the head of SCAP's Diplomatic Section in the late 1940s after the war.

On 15 August 1949, Sebald and his assistant, Richard B. Finn, also an attorney and former language officer, sent the following dispatch to all of the major SCAP offices, in which he expressed DISSEC's understanding of the status of Koreans who were legally residing in Japan as Japanese.

This is arguably the most important single document of many that reveal the various attitudes of different SCAP and Japanese government offices and officials toward Koreans in Occupied Japan during the period leading up to the signing of the San Francisco Peace Treaty on 8 September 1951 and the ROK-Japan talks that began from 21 October just 6 weeks later.

The following representation of Sebald's "Status of Koreans in Japan" dispatch is my transcription of a copy of the dispatch provided me by Simon Nantais on 3 July 2014. The lineation and hyphenation are as received. The [bracketed glosses] and underscoring are mine, as are the comments that follow.

Note that the dispatch is formally from "DS:WJS:RBF:hh" /Mr. Finn 26-5528", which suggests that, while it was from both "William J. Sebald" and "Robert B. Finn", the latter was in charge of preparing the dispatch under the former's direction. See biographical particulars about both officials on the Nationality after World War II: Japan's bilateral talks with ROC and ROK page.

|

CONFIDENTIAL

1. Reference is made to DS' staff study circulated by checknote dated

2. It has been decided by the Chief of Staff that this project should

3. In the absence of a change of policy, it is DS's understanding that:

4. DS recommends that in the interest of stability no punitive or re-

5. The above statement of DS' understanding of SCAP policy with regard . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . W. J. S. . . . . . . . . . CONFIDENTIAL |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

Commentary on text of Sebald's dispatch

William J. Sebald was by then the head of the Diplomatic Section. Richard B. Finn was the most important Foreign Service Officer in the Diplomatic Section.

Both Sebald and Finn were lawyers. Sebald had been trained in Japanese in Japan, and had lived and worked in Japan as an attorney and translator of Japanese laws, before the Pacific War, and had served as an intelligence officer during the war. Finn, after becoming a lawyer, had been trained at the Japanese Language School in Colorado during the war, been deployed in the Pacific as a language officer, then briefly served as a language officer in Occupied Japan. He then resigned his commission, and after passing the Foreign Service Officer exam, he was sent to Occupied Japan to work in the "DIPSEC" that by then was headed by Sebald.

Finn had developed much of the information about "Koreans in Japan", and both men shared the position on the legal status of Koreans in Japan expressed in the 15 August 1949 statement.

Korean Diplomatic Mission in Japan

This refers to the diplomatic mission of the Republic of Korea (ROK).

The Republic of Korea was founded in the southern half of Korea (Chōsen) on 15 August 1948, exactly 1 year before Sebald wrote this dispatch. The Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK) was founded in the north on 9 September 1948. Though both states claimed to be the government of all of Korea, on 12 December 1948 the United Nations General Assembly declared ROK to be the only lawful government in Korea. On 1 January 1949 the United States recognized ROK and the two states exchanged ambassadors. By the end of 1949, 22 other states had recognized ROK. Japan, when surrendering to the Allied Powers in 1945, delegated its sovereignty, including its diplomatic capacity. SCAP thus proxied most of Japan's diplomatic affairs during the Occupation, and Sebald's Diplomatic Section was the principal liaison between SCAP and Japan's Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Though in principle SCAP represented all of the Allied Powers, in practice its "foreign policy" was essentially guided by the United States. ROK had expressed its desire to represent Koreans in Japan, and SCAP considered "recognizing" ROK to the extent of allowing its mission in Occupied Japan to enroll Koreans in Japan into its nationality.

Korean residents in Japan since 2 September 1945

This refers to Koreans who had been residing in parts of the prefectural Interior of the Empire of Japan that became Occupied Japan -- on or before, and since, Japan formally surrendered to the Allied Powers on 2 September 1945.

Korean residents refers to people in Occupied Japan whose family registers were in Korea (Chōsen), whether north or south of the 38th parallel. While some SCAP documents appear to "racialize" the people it calls "Koreans", in principle "Korean" is a civil status defined by membership in a Korean household register. The term "resident" implies a civil status in a Japanese municipal polity, whether as a Japanese or an alien. Korean residents continually in Occupied Japan since 2 September 1945 are Japanese. Koreans with ROK documents are aliens. The status of Koreans who were in Japan illegally is not clear.

2 September 1945 is the date on which the Allied Powers and Japan signed the General Instrument of Surrender. From this date, Japan became legally obliged to accept the terms of the Potsdam Declaration, which included the separation of Korea (Chōsen) from Japan. Numerous postwar laws mark time from this date, on which the Empire of Japan is redefined as the prefectural Interior (内地 Naichi) minus Karafuto and Okinawa prefectures, and a few islands affiliated with Kagoshima, Tokyo, and Hokkaido prefectures.

Special Permanent Residents "2 September 1945" continues to define the status of Special Permanent Resident (特別永住者 Tokubetsu Eijūsha), a perpetual right-of-abode for (1) any alien in Japan who (a) was residing as a Japanese national in the prefectural Interior of Japan on the day Japan surrendered, (b) lost their Japanese nationality on 28 April 1952 as an effect of Japan's formal loss of Taiwan and Chōsen, or (2) any alien lineal descendant such an alien who (a) was born in Japan after 28 April 1952, and (b) has continually resided in Japan. SPRs represent about 50 different nationalities, but most are nationals of the Republic of Korea (ROK), followed by nationals of the People's Republic of China (PRC) or the Republic of China (ROC), and nationals of other countries. Many nationals of other countries are former ROK or ROC nationals.

Chief of Staff

The Army Chief of Staff from 7 February 1948 to 15 August 1949, the date of Sebald's dispatch, was General Omar Bradley (1893-1981).

Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) The Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP) at the time -- General of the Army Douglas MacArthur (1880-1964) -- was accountable to the Joint Chiefs of Staff in Washington, which oversaw the military Occupation of Japan on behalf of the Allied Powers. The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) had dictated to SCAP the original determinations of the boundaries of "Occupied Japan" and the statuses of Koreans (Chosenese) and Formosans (Taiwanese) as "non-Japanese" for purposes of repatriation. Sebald's dispatch makes it clear that SCAP, while in a position to recommend that ROK be allowed to enroll Koreans in Japan in its nationality, was obliged to submit to its recommendations to the JCS for approval, through the Army Chief of Staff, who higher in the chain of command (though Bradley at the time was only a 4-star General while MacArthur was a 5-star General of the Army).

Koreans as used here is a general reference to people whose legal status was defined by territorial affiliation with "Korea" -- the term used by the Allied Powers, hence SCAP, to refer to what is still called "Chōsen" in Japanese. The "Korea" in the English version of the San Francisco Peace Treaty is "Chōsen" (朝鮮) in the Japanese version. The "Korea" in the English version of the 1965 normalization treaty between Japan and the Republic of Korea is "Chōsen" (朝鮮) in the Japanese version but "Han pando" (한반도) in the Korean version, which reflects ROK's preference for "Han" (韓) rather than "Chosŏn" (朝鮮) as the name of the country or territory. In Japanese, "Koreans" were "Chōsenjin" (朝鮮人), which in English is "Chosenese" -- hence my usage when referring to "Koreans" when referring to people affiliated with "Chōsen" whether during or after it was a part of Japan. The terms "Chōsen" and "Chōsenjin" continue to live in legacy law in Japan.

registered Koreans who had relinquished Japanese nationality be entitled to the status of foreign nationals in Japan

This means that -- if a Korean who was legally registered as a resident of Japan had applied to the Korean Diplomatic Mission in Japan for recognition under ROK law as an ROK national, and was so recognized by ROK -- the Korean would lose his or her status as a Japanese national, and therefore qualify for treatment as an alien.

|

Relinquishment of Japanese nationality Had SCAP permitted the Korean Mission in Japan to enroll Koreans registered in Japan into its nationality, such Koreans would lose their status as Japanese nationals and become aliens -- at least in SCAP's eyes. Japan's Nationality Law applied to Japanese in Interior (including Karafuto) and Taiwan registers, but not to Japanese in Chōsen registers, so the legal basis for loss of Japanese nationality would have to be customary rather than statute law -- if not also Occupation Law, i.e., rules established by the Occupation Authorities and enforced by SCAP. Whether SCAP would have insisted that the procedure of enrollment into ROK nationality include a formal oath of abandonment or renunciation of Japanese nationality is uncertain. All that was certain was ROK's certainty that Koreans (Chosenese) in Japan had always been its nationals. SCAP and Japan took the position people legally residing in Occupied Japan as Chosenese would "belong" to Japan until treaties between Japan and one or both peninsular states determined their nationality options. ROK, however, refused to recognize the legality of the Annexation or its effects -- namely, that

Moreover, many Koreans in Japan thought that they had been liberated from their status as Japanese subjects and nationals as a result of Japan's acceptance of the terms of surrender, and were therefore already Koreans, hence aliens, in Japan. Sebald's dispatch later alludes to the problem of Koreans who, though still Japanese, were illegally -- though possibly in good faith -- availing themselves of privileges reserved for aliens. |

The status of Koreans legally in Japan, other than those who hold valid documentation issued by the Korean Government, remains unchanged and they will accordingly continue to be considered Japanese nationals for the purpose of treatment; there is no basis on which Koreans legally in Japan other than those who hold valid Korean documentation can be treated as other than Japanese

This in effect defines the following 3 categories of people in Japan who are "Koreans" (Chosenese) on account of being members of household registers in "Korea" (Chōsen).

- Koreans legally residing in Japan as Japanese

i.e., not entitled to treatment as foreigners

Though Japanese, they were regarded as aliens under

1947 Alien Registration Order, hence should have cards

= Practically all "Koreans in Japan" - Koreans legally residing in Japan as ROK nationals

i.e., foreign nationals with ROK documents

= The few ROK nationals who SCAP permitted

to enter Occupied Japan, including of course

members of the Korean Diplomatic Mission in Japan - Koreans illegally residing in Japan

= Koreans who had illegally entered Occupied Japan,

including some who had formally repatriated to Korea from

Occupied Japan then later returned without documentation

OSS ration card article

OSS ration card articlePacific Stars and Stripes 21 March 1950, page 2 |

OSS cards

Not "Office of Strategic Services" ID cards -- but "Overseas Supply Store" ration cards. The cards were issued by the Tourists and Service Division of SCAP's Economic and Scientific Section (ESS), one of the recipients of Sebald's dispatch. Such cards were allowed their bearers to shop at designated OSS outlets in parts of Japan with substantial numbers of Occupation Personnel. One of the better known outlets in Tokyo was the Meijiya building in Kyobashi. Military and civilian personnel, and other qualified United Nations nationals, could obtain the cards, which gave them access to imported goods unavailable in Japanese stores. Japanese -- including Koreans who had remained in Occupied Japan, and Taiwanese who had not migrated to ROC nationality -- were not allowed ration cards. Local black markets coveted goods from OSS outlets, which motivated fraternization between Japanese (including Koreans) and Occupation Personnel.

those who do not possess Japanese Alien Registration Cards or Korean documentation

In other words, Koreans illegally in Japan. These Koreas would have included those who had been in the prefectures on or before, and since, 2 September 1945, and those who had smuggled themselves into the country after that date. The former would be those who had failed for whatever reason to register as aliens. SCAP considered them to still be Japanese, but they were regarded as aliens for purposes of registration under the 1947 Alien Registration Order. They would not have had Korean documentation. The later would include Koreans who had been in the prefectures at the end of the war but repatriated from Occupied Japan to the peninsula, then returned to Occupied Japan, and Koreans who had been in the prefectures in the past and had reason to come again, and Koreans who had never been in the prefectures but had reason to come. It all came down to personal circumstances.

no punitive or re[tr]oactive action be taken with respect to those Koreans who have in good [fa]th been availing themselves of privileges to which they are not entitled

Sebald recognized that SCAP had to take responsibility for the confusion regarding nationality status that led some Koreans to believe that they weren't Japanese, hence were legally above Japanese. Some Koreans in Japan, believing they were aliens, thought they were qualified for treatment on a par with United Nations nationals, who in Occupied Japan had extraterritorial privileges, including special rations not available to Japanese or other former enemy nationals, and in some cases protection from the reach of Japanese courts.

"Liberated people When the war ended in 1945, Chosenese and Taiwanese got the impression that they were "liberated peoples" and no-longer Japanese. This impression was encouraged by SCAP, which pursuant to a late-1945 JCS directive regarded them as "non-Japanese" for purposes of repatriation. If they left Japan for Korea or Formosa for the purpose of repatriation, they left Japanese nationality. If they remained in Japan, they retained Japanese nationality. However, SCAP's nationality policy was not clarified until after late 1946, when the official repatriation window was closed. The 1947 Alien Registration Order -- though recognizing that Koreans in Japan, and Formosans in Japan who had not migrated to ROC nationality, were Japanese nationals -- provided that, for the time being, they were to be treated as aliens for the purpose of alien registration and border control. People subjected to such treatment easily got the impression that, legally, they were aliens. Some felt they deserved to benefit from the privileges reserved for United Nations nationals, who qualified for special rations, protection from Japanese courts, and other forms of extraterritorial treatment.

1950 Nationality Law

Occupation Authorities, meaning SCAP and SCAP-related officials, issued numerous directives and other documents touching upon nationality or status issues related to nationality. US consuls and other Department of State Foreign Service Officers in Occupied Japan also contributed to the flow of paper concerning Japanese nationality, and of course US citizenship, since US consuls were responsible for dealing with US citizenship matters in Japan.

SCAP oversaw Occupied Japan as the authority to which Japan had delegated its sovereignty under the terms of surrender. Hence SCAP was naturally concerned with the full scope of nationality issues that needed to be resolved in the treaties that Japan would conclude with the Allied Powers and other states.

To be continued.

Callanan's transmittal of 1950 Nationality Law to DOS

The US Department of State (DOS) posted officials to Occupied Japan for the express purpose of advising SCAP -- General MacArthur -- regarding US foreign policy interests and keeping DOS abreast of developments in Occupied Japan that might have an impact on policy.

SCAP's first DOS political adviser (POLAD) was George Atcheson (1896-1947), and General MacArthur made him an ambassador. Atcheson was appointed chief of the Diplomatic Section at SCAP's General Headquarters in Tokyo on 18 April 1946, and from 22 April he was SCAP's representative on the Allied Council for Japan.

When Atcheson died in a plane crash near Hawaii on 17 August 1947, William Sebald (1901-1980), the deputy chairman of the Allied Council for Japan, became acting POLAD. From October 1948, Sebald was appointed POLAD with the rank of minister, and served in this post for the duration of the Occupation of Japan.

The US Political Adviser to GHQ/SCAP was the equivalent of the US ambassador to Japan during the Occupation, and its offices were the equivalent of US consulates -- hence the following correspondence from US POLAD, Yokohama to DOS, with copies to US POLAD offices in Tokyo, Kobe, Fukuoka, Nagoya, and Sapporo.

Leo J. Callanan (1900-1982), as American Consul General, had been the U.S. Consul General in Hankow, 1949 during the revolution when the People's Republic of China was established and the Liberation Army drove the government of the Republic of China into exile on Taiwan. George Atcheson, too, had come to his post in Japan, after World War II, from diplomatic service in China.

The following letter to DOS in Washington, from Leo J. Callanan, American Consul General in Yokohama, dated 20 September 1950, is especially interesting for how it reflects both the depth and shallowness of understanding among even Americans who had professional reason to be familiar with nationality issues.

I am indebted to Simon Nantais, at the University of Victoria, for a scan of a copy of Callanan's letter, consisting of two pages and enclosures, which he retrieved from GHQ/SCAP archives (document 794.08/9-2050).

|

FOREIGN SERVICE OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

Enclosed are five copies of Japan's new Nationality Law No. 147, which went into effect on July 1, 1950. The official English translation of this law appears in Official Gazette Extra No. 41, commencing on page 39. The new law, which was drafted by Japanese officials in cooperation with the Occupation Legal Section, is extremely concise. Its principal purpose is to insure conformation of nationality principles with the new Constitution of Japan, which went into effect May 3, 1947. To accomplish this purpose, discrimination based on the family system in the acquisition and loss of nationality has been extablished. The new law follows the traditional Japanese principle of jus sanguinis in transmitting nationality. Japanese nationality is acquired in general by birth of [sic = to] a Japanese father, and also by naturalization. Japanese nationality may be lost by voluntary acquisition of a foreign nationality, by renunciation, or by failure to take steps to retain Japanese nationality in the case of persons automatically acquiring foreign nationality at birth. Of principal interest in connection with American citizenship work in Japan is the retention in the new Japanese law of the principle that a child of a Japanese national may be naturalized as a Japanese by permission of the Attorney General if the child has a domicile in Japan; this principle, which is not included as a form of naturalization (kika), is similar to the principle of recovery (kaifuku) previously employed by Japanese nationality law. The new law also provides that Japanese nationals acquiring a foreign nationality by birth in a foreign country will lose Japanese nationality retroactively from birth unless intention to retain Japanese nationality is indicated; this principle has also been employed by previous Japanese nationality law. Also enclosed is a translation of a summary of an article by Mr. Kenta HIRAGA on the new nationality law. Mr. Hiraga, who is one of the leading experts of the Japanese Government on nationality, describes the history of Japanese nationality legislation and discusses some of the principal points of the new law. Ne notes that Formosans and Koreans in Japan will, under the new law, be considered as Japanese for most purposes, although this conclusion will probably be modified by international agreement affecting Japan, Korea and Formosa. He also notes that Japanese courts have handled considerable litigation by Japanese-Americans, attempting to cancel their recovery of Japanese nationality; the decision of the Japanese Supreme Court that it will not handle such cases where the real issue is American citizenship rather than Japaneses nationality and the provision of the new nationality law that a Japanese national must possess a foreign nationality in order to renounce Japaneses nationality will undoubtedly limit such litigation. Mr. Hiraga is thoroughly familiar with problems of the conflict of Japanese and American nationality and it is believed that the enclosed summary of his article is useful in explaining these difficulties and the background of the new law. Whether the extreme brevity of the new Japanese nationality law will conduce to clarity and legal certainty remains to be determined in the light of its future operation.

Leo J. Callanan

Enclosures: Copies to: Tokyo, Kobe, Fukuoka and Nagoya, Sapporo |

||||||||||||||||||||

Callanan's communication is very interesting in that it shows how at least one US consul -- who had come up through the ranks dealing with citizenship and nationality issues -- misconstrued the relationship between Japan's 1950 and 1899 nationality laws, and between these laws the 1890 and 1947 constitutions. Understanding the nationality laws of other states was not, of course, in Callanan's job description, since his authority -- as a US consul -- extended only to US nationality laws.

General foreign service officers bend over backward not to interpret the laws of other countries. Here, of course, Callanan is acting as a consul of the United States, in Occupied Japan, which was under the authority of the Allied Powers, which was dominated by the United States.

Callanan may have prepared the above communication under his own authority -- if not under the direction of William Sebald -- who would have been his boss, as POLAD (Political Adviser) to GHQ/SCAP at the time. The Yokohama branch of POLAD, as a de facto US consulate, was heavily involved in US citizenship confirmations by stranded Americans, including Americans of Japanese ancestry. It also, of course, provided routine services for US citizens, including consular recognitions a marriage to a Japanese or other non-US national, or the securing of a US-issued birth certificate for a child born in Japan.

A number of Callanan's remarks require comment.

"nationality" and "citizenship"

The manner of writing reflects that of an American consul who, as part of his job over the years, had dealt with all manner of nationality and citizenship issues. Hence the clear differentiation between "nationality" (in Japanese law) and "citizenship" in US law.

"conformity of nationality principles"

Callanan implies that there were constitutional "conformity" issues, and that the 1950 Nationality Law took these issues into mind. In fact, the most basic principles of the 1950 law are identical to those of the 1899 Nationality Law. And the 1899 law, as revised in 1916, would have complied with the 1947 Constitution just as well as the 1950 law.

The 1947 Constitution, like the 1890 Constitution, stipulated that qualifications for national affiliation would be determined by statutes, and neither constitution placed any constraints on qualifications. The 1950 Nationality Law contains only one article that mentions "nationality" (kokuseki) by way of giving Japanese nationals the right to renounce their their status as nationals. The 1899 law had no provision for renunciation until 1916, when the law was revised in response to demands by the United States that Japan do something to minimize the occurrence of dual nationality among children born in the United States to Japanese who had settled in America (see more in following commentary).

The 1947 Constitution, unlike the 1890 Constitution, forbids sexual discrimination in laws. Yet the 1950 Nationality Law adopted the same basic affiliation principles as the 1899 law, namely patrilineality in the case of married nationals, which discriminated against Japanese women married to aliens and their children (see more in following commentary).

See 1899 Nationality Law for details.

"discrimination based on family system"

By "discrimination" Callahan appears to mean differentiation of family register statuses such as sex, marital status, and legitimacy. All three statuses had figured in all manner of civil family law in pre-Occupation Japanese laws, and all continued to figure, somewhat modified under the 1947 Constitution, in the 1948 Civil Code and 1948 Family Register Law.

Because Japan's nationality laws have essentially been based on principles of family law in the Civil Code, in turn reflected in the Family Register Law -- and because family registers affiliated with Japan also serve as registers of Japanese nationality -- naturally the new nationality law had to dovetail with "traditional" principles of family law -- at least to the extent that they had survived in the revised Civil Code and the new Family Register Law, both enforced from 1 January 1948.

The sexual "discrimination" was not eliminated until revisions enforced from 1985 (see below). Also from 1985, acquisition by legitimation and recognition became possible -- having been possible under the 1899 law but not under the original 1950 law. The new provisions for legitimation and recognition -- based on traditional principles of "discrimination" in family law -- were revised to eliminate the discrimination from 2009.

See 2009 Nationality Law revisions for details.

"by birth of a Japanese father"

Callanan's remark that "Japanese nationality is acquired in general by birth of [sic = to] a Japanese father" -- actually testifies to the fact that the 1950 Nationality Law did not conform to the letter and spirit of Article 14 of the 1947 Constitution, which mandates that nationals not be discriminated under law because of sex.

Whatever guidance GHQ/SCAP's Legal Section gave Japan regarding patrilineality as a "general" or "traditional" principle is not clear, but the issues was discussed among Japan's lawmakers and legal bureaucrats -- who, of course, had reasons to continue to apply the basic -- familiar and, in fact, globally rather common -- mixture of patrilineal and matrilineal jus sanguinis, and jus soli, principles.

Callanan's "in general" qualification -- commonly made by writers on Japan's nationality laws -- refers to cases of children born to married parents -- because a child born to an unmarried Japanese woman, under both the 1899 and 1950 laws, could acquire Japanese nationality at time of birth. Also, under both laws, children born in Japan to parents both of whom were stateless, or both of whom were unknown (foundlings), became Japanese through jus soli principles.

See 1950 Nationality Law and 1985 Nationality Law revisions for details.

"steps to retain Japanese nationality"

Callanan observes that the 1899 Nationality Law also had rule concerning intention to retain nationality. These rules were introduced in 1924, after the United States demanded that Japan take more positive measures than it had taken in 1916 to minimize dual nationality among the US-born children of Japanese nationals who had settled in the United States. Japan applied the 1924 revision to a number of American hemisphere states which, like the United States, had primarily jus soli (place-of-birth) laws.

See 1899 Nationality Law for details.

"kika" and "kaifuku"

Callanan's remarks are a bit odd because the 1899 Nationality Law clearly facilitated naturalization (kika) for children of Japanese nationals who are domiciled in Japan. Recover of nationality (kaifuku) has been possible only for domiciled aliens who had previously possessed Japanese nationality.

"Formosans and Koreans in Japan"

Callanan's remarks about Kenta Hiraga's discussion of some of the principles in the new law are interesting -- though the new law had nothing to do with -- nor could it have had anything to do with -- the present or future status of Japanese whose nationality was linked with Formosa (Taiwan) and Korea (Chosen) as parts of Japan.

The month after Callanan wrote this communication -- i.e., in October 1950 -- the first volume of Hiraga's two-volume bible on nationality law was published. The second volume was published in October 1951, a month after Japan had signed the San Francisco Peace Treaty and began talks with the Republic of China and the Republic of Korea regarding post-Occupation settlements.

The first volume of Hiraga's work contains what was then considered the definitive statement on nationality in Taiwan, Karafuto, and Taiwan (Hiraga 1950-1951, Volume 1, pages 132-133, 140, 153-170). Today, over half a century later, his observations still qualify as clear descriptions of the standards by which Japan continues to regard legacy nationality issues.

See Hiraga 1950-1951 for details.

"to renounce Japanese nationality"

The 1899 Nationality Law was revised in 1916 in response to US demands that Japan permit US citizens who were also Japanese nationals to renounce their Japanese status. Article 22 of the 1950 Constitution stipulates "Freedom to divest nationality inviolate" -- but this obviously applies only to Japanese nationality, for Japan has no legal authority over the nationalities of other states.

The main text the 1950 Nationality Law, as promulgated or as later revised, does not actually stipulate that a renouncer must have another nationality. However, international conventions have strongly discouraged denationalization that results in statelessness, and Japan is among the many states that requires renunciation applicants to possess another nationality, specifically of a state Japan recognizes.

"considerable litigation by Japanese-Americans"

Callanan's "hyphen" should not be taken to mean dual nationals as such -- but Americans of Japanese ancestry, in Japan, many of whom the United States regarded as having lost their US citizenship because they were viewed as having in some manner participated on Japan's side during World War II, or had voted in the first postwar election in 1946, as Japanese nationals.

Most such Americans did not intend to lose their US citizenship. And not a few, unable to return to the United States during the war, had activated the Japanese nationality retained by their parents, or otherwise acquired Japanese nationality, under wartime pressure in Japan. As a condition for reinstatement of their US citizenship, they were generally required to show evidence of separation from their Japanese status -- hence Callanan's statement about "considerable litigation".

There was also considerable litigation in the United States concerning reinstatement of US citizenship lost by some Americans of Japanese ancestry in connection with their refusal to swear loyalty to only the United States, among other causes. Isamu Noguchi was one such person who had to go to court in the United States to recover his lost US citizenship.

See Prominent people of mixture for details about Noguchi's situation.

Some cases were initiated by the United States against Americans it charged with treason for acts they were alleged to have committed in Japan during the war. One such case involved Tomoya Kawakita -- who had returned to the United States, after having his US citizenship confirmed on the basis of affidavits and other documents he submitted to the American Consul at Yokohama December of 1945 -- which was before Callanan's time.

See The Kawakita treason case for details.

"the extreme brevity of the new law"

This is one of the more interesting remarks by Callanan. Bear in mind that, as an American consul, he was generally at home in the extremely convoluted status laws of the United States. The 1950 Nationality Law was quite a bit simpler and shorter than the 1899 law, but even the 1899 law and its revisions were simple and short by US standards.

Having said this, the nationality law -- like many such laws -- came with enforcement regulations for the local registrants and other officials who had to carry out the law's provisions. Moreover, the 1950 law came with the baggage of all preceding laws, regulations, bureaucratic decisions, and court decisions related to nationality and status tantamount to nationality in Japan.

Callanan concerns that the brevity of the 1950 law might not be conducive of clarity in its future operation turned out to be wasted. What proved to be a problem was the utter clarity with which the new law discriminated on the basis of the family system in Japan -- to paraphrase Callanan's odd remark (see above).

Summary of Hiraga's overview of 1950 Nationality Law

Consul General Leo J. Callanan's 20 September 1950 dispatch to the Department of State (above) included an enclosure which he described as "a translation of a summary of an article by Mr. Kenta Hiraga on the new nationality law" (page 2). The enclosure runs 12 pages of single-spaced typescript. I received a pdf file of page 5 from Simon Nantais on 13 October 2010 and pdf files of the other pages 29 May 2011.

Hiraga Kenta (1912-2004), a career legalist who specialized in civil law, was deeply involved in family system issues by the early 1940s. After World War II, with many other government and civilian specialists, he was involved in revising the Civil Code and Family Register Law, effective from 1948, which had to be brought into line with the principles of the 1947 Constitution.

Hiraga became particularly experienced in nationality issues, participated in the drafting of the new 1950 Nationality Law, and wrote the earliest guides to the law, including the article digested here, published shortly before the law came into effect. In the fall of 1950 he published the first volume, and in the fall of 1951 the second volume, of what quickly became the standard commentary on nationality law in Japan and remained so until the 1970s.

See Hiraga 1950-1951 a review of Hiraga's compendium and a longer biographical note.

This publication, which appeared on the heels of the 1950 Nationality Law, is in many respects the bible of early postwar Japanese nationality law studies. Though superseded by Tashiro 1974 as a guide to the workings of the 1950 law, it remains more valuable for certain historical content not found in Tashiro.

Hiraga's general description of the reasons the 1899 Nationality Law had to be revised is generally reliable. From the viewpoint of constitutional and civil (especially family) law, the revisions were indeed "substantial" -- but only to extent that they reflected basic changes in the legal standing of individual rights as provided in the 1947 Constitution and in the Civil Code as revised from 1948. With respect to its principles for determining who belongs to the nation as a matter of birth or through naturalization, the 1950 Nationality Law was essentially no different than the 1899 law. See comments following partial transcription of the summary translation (below).

Quality of summary translation

The enclosure represented as a "translation of a summary" of Hiraga's article appear to be a digest of article with some direct citations. While parts of the enclosure are extremely lucid and well phrased, others show construction marks -- some perhaps intentional (like my own very heavy "structural" marks), but a few seemingly left in the haste of paraphrasing and editing. Not having seen the original article, however, I cannot verify the literal accuracy of the enclosure as either a translation or a summary.

While the enclosure appears to represent the viewpoints Hiraga expressed elsewhere about the same time, especially in his 1950-1951 compendium on nationality law, it does not entirely reflect his thinking about the old and new laws. The article was very likely a finger exercise for the compendium (see below).

Transcription and comments

Here I have transcribed selected parts of the enclosure and, after the partial transcription, commented on phrases with purple highlighting. Not having seen Hiraga's article, my comments address only the statements in the received document rather than what Hiraga might actually have written.

|

Summary translation of article by Hiraga Kenta on 1950 Nationality Law |

||||

|

Japanese article published circa 1 June 1950 |

||||

|

SECURITY: UNCLASSIFIED Enclosure 2 of

ON THE NEW NATIONALITY LAW

FORWARD The draft of the new Nationality Law was approved by the House of Representatives on April 15, 1950 and by the House of Councilors on April 26. The new Nationality Law was promulgated on May 4 as Law No. 147, and will take effect from July 1, 1950. The Nationality Law currently in force since 1899 has been substantially revised. As one who participated in the drafting of the new Nationality Law, I wish to make a summary explanation of it. Hereinafter the Nationality Law currently in force, Law No. 66, 1899, will be referred to as the old law and New [sic] Nationality Law as the new law. The Law amending a part of the Family Registration Law in connection with the enforcement of the Nationality Law was promulgated on the same day as Law No. 148, to take effect also on July 1, 1950. HISTORY OF LEGISLATION OF THE NATIONALITY LAW The concept of nationality meaning the qualification as a constituent of a nation has developed along with the concept of a modern nation. Until then nationality had been interpreted as the relation of allegiance to a king, who is the sovereign. The definite concept of nationality originated in the Napoleonic Code of 1804. This code has been used as a pattern of nationality laws in modern European countries. The Japanese Nationality Law owes much to the French Code. It needs no mention that Japan was born as a modern nation in the Meiji era. The first Nationality Law of Japan was promulgated in 1873 as Supreme Council Order No. 103. This order had no general provisions concerning acquisition or loss of Japanese nationality, but merely prescribed freedom of marriages between Japanese and aliens and acquisition or loss of nationality as a result of such marriages. The provisions of that order may be summed up as: - 2 -

[ Rest of page omitted ] - 3 - [ Omitted ] - 4 - [ First paragraph omitted ] As is evident from the reasons given above the new law is the extension and development of the old law. Several steps have been advanced toward the ideal of freedom of nationality and prevention of conflict of nationality. In this article emphasis is laid on that part of the new law which differs from the old law. With the termination of the war various problems latent heretofore from the standpoint of the Nationality Law have suddenly come to the fore. Under the new Constitution all matters previously disposed of by administrative means have now been brought into law court for review and decisions. These problems have chiefly arisen from the mutual relations of nationality laws of Japan and the United States concerning Japanese "Nisei" born in the United States. One of the most conspicuous instances was in relation to the provisions concerning loss of nationality (citizenship) in the American citizenship law and the provisions concerning restoration concerning restoration (Kaifuku) of nationality in the old law. Reference is made to "Recovery of Japanese Nationality as Cause for Expatriation in American Law", by Thomas L. Blakemore, The American Journal of International Law, Vol, [sic] 43, No. 3, July, 1949, The Translation given in the HOSO JIHO), Vol. II, No. 4, will be valuable to Japanese lawyers. Main points I. Article 10 of the Japanese Constitution provides in the same way as Article 18 of the old Constitution that "qualifications as a Japanese national shall be prescribed by law". This means that the loss or acquisition of Japanese nationality shall be prescribed by written laws and regulations, and that such laws must be enacted by the Diet. It is a matter of course that the new Nationality Law carries out the provisions of the Constitution. That a country prescribes qualifications of its national [sic] is provided in Article 1 of the Nationality Treaty of 1930, wherein it is prescribed that: "It is up to the authority of each state to decide by its internal law who shall be its own nationals. Such laws shall be recognized by other countries as long as they are consistent with international treaties, international customs, and the principle of generally recognized laws concerning nationality." As provided herein, there must be a general principle in the international law that a country has a sole right to decide the status of its own nationals. A country has - 5 - no authority to make a final decision as to whether or not a specified individual has the nationality of another country. A state is a community of men, and who shall constitute the community has bearings on the interests of the community. Therefore, generally the community itself decides who shall constitute the community. With the exception of cases where a power superior to the community dictates, a country is not compelled by other country to recognize an individual as a constituent of the community. The Law Governing Disposition of Chinese Overseas Residents promulgated by the Government of the Republic of China on June 22, 1946, provided that Formosan residents should automatically recover Chinese nationality as of October 25, 1945. We do not question this from the standpoint of internal law of China, but we have a question as to the validity of this law from the standpoint of the international law. Although it is devinitely [sic = definitely] anticipated as a result of acceptance of the Potsdam Declaration that Formosa will be outside Japan's territory, yet pending conclusion of a peace treaty it cannot be interpreted that Formosans already have definitely lost their Japanese nationality. At least the Japanese Government holds that Formosans have still Japanese nationality. However, in view of actual situations where Formosans are substantially similar to foreigners, the Japanese Government treats Formosans as foreigners on specific matters. For instance the Alien Registration Ordinance regards Formosans along with Koreans as aliens in the application of this Ordinance. Therefore, applications for naturalization by Formosans are in all cases rejected on the ground that they lack the prerequisite that they are aliens. This applies also to Koreans. Regarding the suit for confirming the nationality of Kiyoshi Honda, in Honda vs State, dated Dec. 20, 1949 (Supreme Court Report Vol. 3, No. 12, P. 507) the opinion that "an appeal to confirm that plaintiff possesses American citizenship is a matter of the jurisdiction of Untied States Courts and not for Japanese courts" is right in this sense. There are, however, not a few questions regarding the propriety of the conclusions of this decision. [ Last paragraph omitted ] - 6 - [ Omitted ] - 7 - [ Omitted ] - 8 - [ First paragraph omitted ] A general explanation concerning the new Nationality Law ends here, and a summary explanation regarding acquisition and loss of nationality in the new law follows belows: [sic]. ACQUISITION OF NATIONALITY. 1. [sic] Birth. Japanese nationality is acquired by birth. It is a well known fact in the acquisition of nationality by birth there are two principles of Jus Soli and Jus Sanguinis (place and blood principles). Japan has adopted the blood principle since the compilation of the Personal Affairs Chapter of the Old Civil Code, and adopted the place principle only on deserted children and on children of stateless parents. The new law has also followed the tradition. The provisions of Article 2 of the new law provide that a child acquires Japanese nationality in the following cases:

As is evident from the above as regards acquisition of nationality by birth the new law is entirely the same as the old law with the exception of the abrogation of Article 2 of the old law based on the family system. That the new law has, as in the - 9 - past, followed the blood principle of paternal lineage is because it is intended as far as practicable to prevent conflict of nationality. The adoption of paternal lineage blood principles is confined merely to use of the nationality of the father as a standard for determining the nationality of child, and does not directly discriminate in the mutual legal positions between father and mother. II. Naturalization (Kika) 1. Legal nature of naturalization. Another cause for acquisition of Japanese nationality is naturalization. The new law provides naturalization in Article 3. It is provided therein that an alien may acquire Japanese nationality through naturalization, and that in order to be naturalized permission of the Attorney General is necessary. There is no fundamental change in the naturalization between the old and new laws. The meaning of such terminology as naturalization, differs in each country according to legislation. It is impossible to make a common definition. Suppose that the term naturalization is defined to mean: "An alien desires to become a subject (or citizen) of a state, and the state grants him (or her) nationality". However, conditions, procedures, and validity differ greatly according to special conditions of each country. With regard to the naturalization system in Japan it is necessary to generally clarify the following points: Naturalization is an act which creates a general status of nationality through granting of permission by an administrative organization of the state (Attorney General) upon application for permission for naturalization made by a specified individual. Namely, naturalization consists of application and permission, or a contract under the public law, [sic] Therefore, it is necessary that the application for naturalization be made in a valid form. Naturalization cannot be permitted without an application therefore. Even if permission is granted in such a case, naturalization is not effected. Also the application must be made by the will of the person who desires naturalization. An application by an agent is not permitted. In accordance with the provisions of Article 11 in case the person who desires naturalization is a minor under 15 years of age, an application for naturalization may be filed by his (or her) legal representative. In this case only the legal representative (no other) can file a valid application. Therefore, when the applicant is over 15 years of age, an application made for him by his agent is invalid even when a permission has been granted. An applica- - 10 - tion for naturalization must be made by the will of the person who has right of application. Even though the application has been made by the person who has right to do so, if it is found that the application was made under irresistible duress or not by free will of the applicant, a permission for naturalization, even if granted, shall be invalid. However, in case the application is found to have been made under the will of the proper applicant, the permission already granted for naturalization stands valid; and the applicant cannot revoke his application, even when there exists flaws in expression of will such as fraud, or duress. An interpretation of the above effect was made after the termination of the war in connection with a case at court regarding validity of restoration, during the war, of nationality by Japanese Nisei born in the United States. Mr. Blakemore's article before cited is valuable regarding restoration of nationality made during the war. [ Rest of page omitted ] - 11 - [ Omitted ] - 12 - [ First lines omitted ] LOSS OF NATIONALITY I. Voluntary acquisition of foreign nationality [ Omitted ] II. Automatic renunciation of nationality Automatic renunciation of nationality is provided for under Article 9, which aims at prevention of conflict of nationality. Namely, Japanese born in a country which adopts the place principle in acquisition of nationality through birth is required to express a will for reservation of Japanese nationality in accordance with the provisions of the Family Registration Law, because such birth arises the positive conflict of nationality through acquisition of nationality of country of birth by birth. |

The above summary has a number of problems. Here I will focus on those related to the underscored phrases.

"substantially revised"

While true that the old law was "substantially revised", the most essential provisions of the new law -- which stipulated qualifications for nationality at time of birth -- were essentially the same as those of the old law. It is not that the revisions were not important in the light of changes in constitutional and civil law, but that they were overshadowed by the retention of patrilineality.

"first Nationality Law of Japan"

While Great Council of State Proclamation No. 103 of 1873 made provisions for gain and loss of what was tantamount to nationality in alliances of marriage and adoption between Japanese and aliens, it was not quite a "nationality law".

"freedom of marriages between Japanese and aliens"

Nor did the 1873 proclamation quite "prescribe" or otherwise provide for "freedom in marriage between Japanese and aliens". The proclamation provided that a head of household apply for permission to effect an alliance of marriage or adoption involving an alien. Japanese in another country who married an alien were to request permission of a Japanese official in the country, or in a nearby country, and the official had the power to sanction or not sanction the marriage.

"acquisition or loss of nationality"

The 1873 proclamation did not in fact speak of "nationality" -- if this word represents "kokuseki" (国籍), a term that was not coined until later. The proclamation speaks only of gaining or losing "the standing [status] of being Japanese" (日本人タルノ分限 Nihonjin taru no bungen).

Such a standing was based on membership in a household register affiliated with Japan's sovereign territory according to the 1872 Family Register. This law, more than the 1873 proclamation, deserves to be regarded as Japan's first de facto "nationality law". The changes in standing stipulated in the 1873 proclamation were merely effects of status acts under the 1872 register law. In other words, permission to enter into an alliance of marriage or adoption involving an alien would occasion changes in family register status.

This is still true today, in the sense that family register status is tantamount to nationality status. The Nationality Law merely facilitates register status changes related to the enrollment of people having no legal status (such as at time of birth) or aliens (later in life) as Japanese, or the disenrollment of Japanese (who renounce or lose their nationality).

Japan's first true "national status" law as such was part of the promulgated but never enforced French-style Civil Code of 1890. This code used the expression "national standing [status]" (国民分限 kokumin bungen) (see "Old Civil Law" below).

"nationality (citizenship) in the American citizenship law"

Note that "nationality" is the term used on United States passports as the status term recognized under international law, while for purposes of domestic law US passports refer to the possessor as a "citizen/national" of the United States, since US domestic laws differentiation between "citizens" and "nationals". There is no "American citizenship law" as such. Japan's domestic laws define neither "citizen" nor "citizenship" as such, but only "national" as a matter of possessing "nationality".

Thomas L. Blakemore

The enclosure raises and often returns to problems of dual nationality and recovery or "restoration" (回復 kaifuku) of nationality. It twice refers to Blakemore in connection with problems involving "Japanese 'Nisei' born in the United States" (page 4) or "Japanese Nisei born in the United States" (page 10). It also mentions the 1949 Supreme Court decision in Japan concerning the American citizenship of Kiyoshi Honda (page 5).

The summary makes explicit and full reference to "Recovery of Japanese Nationality as Cause for Expatriation in American Law", by Thomas L. Blakemore, noting that it was published in The American Journal of International Law, Vol. 43, No. 3, July 1949, and adding that "The Translation given in the HOSO JIHO), Vol. II, No. 4, will be valuable to Japanese lawyers" (page 4). Later it repeats that "Mr. Blakemore's article before cited is valuable regarding restoration of nationality made during the war" (page 10).

The late 1940s saw a splurge of cases in the United States, but also in Japan, involving people whose American and/or Japanese nationality required legal clarification. Blakemore's article, concerning cases up to the time he wrote the article, was cited in later cases. See, for example, The Kawakita treason case.

The translation of Blakemore's article appeared in the April 1950 issue of Hōsō jihō, hence two months before Hiraga's article. An 4 March 1994 obituary described Thomas L. Blakemore (1915-1994) as follows (The New York Times website).

|

T. L. Blakemore, 78, Expert on Japan's Law [ Omitted ] Mr. Blakemore practiced law in Tokyo for 38 years as the founder and senior partner of the firm of Blakemore & Mitsuki. Mr. Blakemore completed his studies of Japanese law at Tokyo University and was admitted to the bar there in 1950. He was one of the few foreign lawyers allowed to practice in courts there at the time. From 1946 to 1949 he served in the government section of the headquarters of Gen. Douglas MacArthur in Tokyo. Mr. Blakemore helped revise the Japanese civil and criminal codes from authoritarian to democratic. He also translated the Japanese criminal code into English. [ Omitted ] Mr. Blakemore earned a law degree from the University of Oklahoma in 1938 and did postgraduate legal studies at Cambridge University and Tokyo Imperial University until the outbreak of World War II. During the war he was an Army captain with the Office of Strategic Services in China. [ Omitted ] |

Given Blakemore's long association with GHQ/SCAP, the timing of the translation in relation to his own interest in nationality conflicts, and the general legal precision of the summary translation, to say nothing of the repeated references to problems involving "Nisei" -- I would not be surprised if Blakemore himself didn't have a hand in preparing the summary translation of Hiraga's article.

An even more seasoned American legalist -- who had studied, lived, and worked in Japan, and translated numerous Japanese laws before the war -- was William J. Sebald (1901-1980). Sebald was a US Foreign Service Officer in Occupied Japan from 1947-1952, during which he served in various posts, some concurrently, including U.S. political adviser (POLAD) to SCAP, the head of SCAP's Diplomatic Section, and a member and then chairman of the U.S. Allied Council for Japan. As a political adviser of ambassadorial rank, he participated in the peace treaty negotiations from 1949-1951. He was also instrumental in facilitating talks between Japan and ROC and Japan ROK after the signing of the peace treaty. And presumably, as SCAP's chief POLAD, he was Leo L. Callanan's boss. Could Sebald himself have been involved in the preparation of the summary translation?

There were, of course, many people in Occupied Japan who were sufficiently bilingual, and familiar with legal jargon and style, to have cranked out the summary translation -- never mind its occasional oddness of usage and opacity. My point is that there was no shortage of legal talent within GHQ/SCAP or, say, the US Consulate in Yokohama, or at their beck and call.

The Occupation of Japan was, above all, driven by attention to legal details. A few details were overlooked in the rush to revise Japan's laws. But nationality was too important an issue to ignore. Hiraga, above all, understood that the Nationality Law should have been revised when the Civil Law and Family Register Law were revised, effective from 1 January 1948. This understanding on his part -- though not alluded to in Callanan's enclosure -- is clear in the first volume of his 1950-1951 compendium (see below).

"qualifications as a Japanese national shall be prescribed by law"

This is a close paraphrase of Article 10 in the 1947 Constitution, though technically "Japanese" should be "national of Japan". Article 18 in the 1890 Constitution similarly provided that laws would determine the qualifications of being a subject of Japan.

The common use of "Japanese" is English tends to conflate Japanese terms which are metaphorically different. The terms in the 1890 and 1950 constitutions are actually "Japan subject" (日本臣民 Nihon shinmin) and "Japan national" (日本国民 Nihon kokumin).

The 1899 Nationality Law characterized those who possessed Japan's "nationality" (国籍 kokuseki) as "Japanese" (日本人 Nihonjin), following earlier practices of referring to people in Japan's population registers being of "the standing [status] of Japanese" (日本人の分限 Nihonjin no bungen). The personal status articles of the 1890 Civil Code defined the qualifications for "national standing" (国民分限 kokumin bungen), which became "nationality" in the 1899 Nationality Law. The 1950 Nationality Law speaks only of "national" (国民 kokumin).

Of interest here is the remark that "This means that the loss or acquisition of Japanese nationality shall be prescribed by written laws and regulations, and that such laws must be enacted by the Diet." Regulations include measures determined by competent ministries, in this case the Ministry of Justice, which supervises the Nationality Law.

"Law Governing Disposition of Chinese Overseas Residents"

What the received translation of Hiraga's article calls the "Law Governing Disposition of Chinese Overseas Residents" was more literally the "Law regulating the disposition of nationality of Taiwan sojourners residing outside" (Big5 在外台僑國籍處理辦法, GB 在外台侨国籍处理办法, JIS 在外台僑国籍処理弁法). The regulation, promulgated by ROC's Executive Yuan on 22 June 1946, made the following provisions for the recover of Chinese nationality by overseas Taiwanese, according to Chiu Hungdah (Chiu 1990, page 54, see Chiu 1990 for particulars).

|

(1) An overseas Taiwanese may register with a Chinese embassy or consulates [sic] (or representative) to recover his or her Chinese nationality. In making registration, he or she shall present two overseas Chinese to prove that he is truly a native of Taiwan. The embassy, consulate or representative concerned shall issue a certificate of registration to the registering overseas Taiwanese. This certificate shall have the effect of a certificate of nationality (Arts. 2 and 3). (2) An overseas Taiwanese who is unwilling to recover his or her Chinese nationality may submit an announcement of the decision to the Chinese embassy, consulate or representative in the country where he or she resides by 31 December 1946 (Arts. 3 and 4). (3) The legal status and treatment of an overseas Taiwanese who has recovered Chinese nationality shall be exactly the same as that of an overseas Chinese (Art. 5). |

A decree issued by the military government of Governor-General Chen Yi in Taiwan on 12 January 1946 had already declared that Taiwanese would be considered to have recovered their Chinese nationality as of 25 October 1945. The regulation, promulgated by ROC's Executive Yuan on 22 June 1946, made the following provisions for the recover of Chinese nationality by overseas Taiwanese, according to Chiu Hungdah (Chiu 1990, page 54, see Chiu 1990 for particulars).

ROC, while recognizing its predecessor's cession of Taiwan to Japan in 1895, naturally (from a political standpoint) and correctly (from a legal standpoint) took the position that Taiwanese had not voluntarily lost their nationality in 1895. Hence those who chose to recover their Chinese nationality would be regarded as having all the rights of Chinese who had never lost their nationality -- unlike those who had regained their nationality after voluntarily losing it (Chiu 1990, page 53).

"Formosans and Koreans"

The formal recovery of Chinese nationality by Taiwanese outside China -- i.e., overseas Taiwanese -- would obligate the host country to treat the person as any other ROC national. The Government of Japan, its diplomatic authority in SCAP's hands, was of course obliged to recognize such Taiwanese as Chinese. But Japan, with SCAP's understanding, was also in the position of having to regard them as still possessing its own nationality. Hence the wording of Article 11 in the 1947 Alien Registration Order (which see for details). And hence the inability of Formosans (and Koreans) to naturalize.

Under the legal status rules reflected in the Alien Registration Order, Taiwanese (Formosans) in Occupied Japan became essentially Chinese as well as Japanese nationals. This was not the case for Chosenese (Koreans) in Occupied Japan, who also continued to possess Japanese nationality, but were unable to register as nationals of either of the Korean governments established on the peninsula in 1948.

SCAP recognized the Republic of Korea to the extent of permitting it to establish a mission in Japan. And though ROK had promulgated a nationality act in 1948, which provided for the acquisition of people in Japan who it considered Korean, SCAP did not permit ROK's mission in Occupied Japan to engage in nationality enrollment. Not until after Japan and the Republic of Korea (ROK) established normal diplomatic relations in 1965 were Chosenese in Japan who wished to be ROK nationals able to gain its nationality in Japan's eyes. Those who wish to be DPRK nationals still have no way to legally gain such status in Japan.

"Old Civil Code"

The revised Civil Code that came into effect from 1948 (and the Civil Code today) is the 1898 Civil Code. "Old Civil Code" appears to refer to the French-style "Boissonade Civil Code" promulgated in 1890 but never enforced. "Personal Affairs Chapter" appears to refer to the "Personal matters volume" (人事編 Jinji hen), Chapter 2 (第二章) of which (Articles 7-18) concerned "National standing [status]" (国民分限 Kokumin bungen).

The Old Civil Code provided for national standing at time of birth under the following conditions (Article 7, my translation).

|