Hochi early issues

News dispatches by postal conveyance

By William Wetherall

First posted 28 January 2010

Last updated 20 March 2010

Founding and development

Postal agency

|

Newspaper

|

Wood to metal

|

Pamphlet to broadsheet

|

Particulars

|

Language

Hochi 11 Meiji 6-8 (1872-9)

Country, people, minds, science

|

Newspaper history

Hochi 27 Meiji 5-11 (1872-12)

Begging for alms prohibited

|

Tokyo's regulations on public behavior

Hochi 39 Meiji 6-2 (1873-2)

Nagasaki Chinatown fire

|

Posting of official to Chosen

Hochi 51 Meiji 6-5 (1873-5)

Mori Arinori and American school regulations

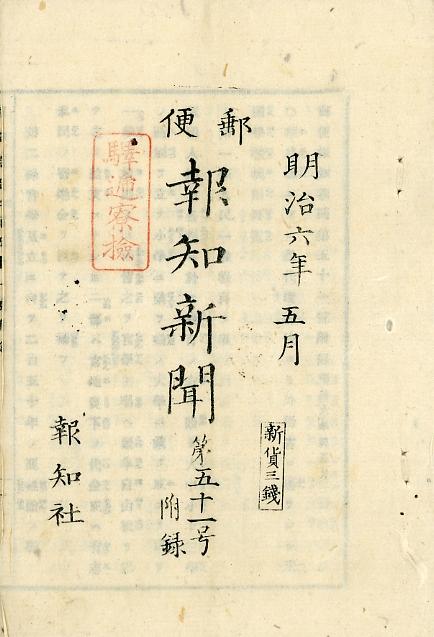

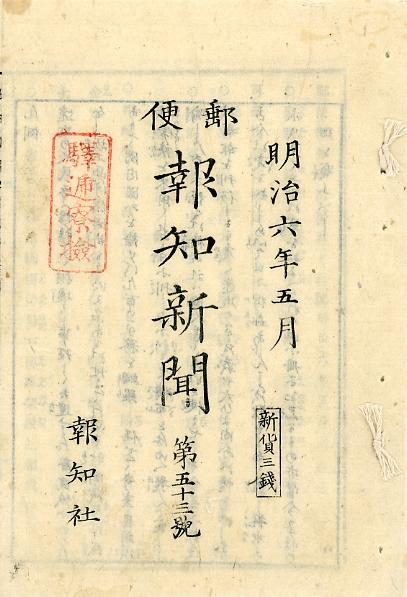

Hochi 53 Meiji 6-5 (1873-5)

"Japan made" goods in New York

|

Tokyo beef lovers beware

Hochi 63 Meiji 6-6-12 (1873-6-12)

German employed by Nagoya hospital

|

Painful misfortunes of Asia's people

Sources and commentary

Kawabe on Yorozuya Heishiro, Rikugo sodan, and Hochi shinbun

|

Note on Yorozuya Heishiro

Founding and development of Yubin hochi shinbun

As its name implies, Yūbin hōchi shinbun (郵便報知新聞) or "Postal dispatch news", was a vehicle for news based on dispatches sent by post. This meant, originally, the use of the postal system to both gather and disseminate news.

First came the postal system, then the paper. The paper eventually weaned itself off the postal bureaucracy.

Kawabe on founding of Yubin hochi shinbun

Kisaburō Kawabé makes the following observation about the start of Yubin hochi shinbun (Kawabe 1921, page 39, see Sources below).

|

Having been stimulated by the central government's example [of publishing and distributing bulletins featuring various news reports], organs were published by prefectural authorities, numbers of private newspapers appeared, and by the end of 1868 there were ten official gazettes and fifteen private papers. They had few editorials, and the greater part of the paper was filled with general news of the civil war which was going on at that time. The following article by Mr. Ishikawa illustrates the situation of those days:

|

Ishikawa's article, as cited by Kawabe, jumps to an overview of prefectural papers. Note 1, page 40, gives the source of Ishikawa's article as "Hanzan Ishikawa, special article in Shimbun Kogiroku, pp. 5-6." The bibliography lists an undated book, "Dai-Nippon Shimbun Gakkai. Shimbun Kogiroku (Transcripts of Lectures on Journalism)." It also lists two articles by Ishikawa Hanzan, dated 1915 and 1919, on the development of newspapers.

The 1910s marked half a century since the last years of the Tokugawa period and the start of the Meiji era. Kawabe's book, published in 1921, represents a splashing on the shores of contemporary English writing on Japan the wave of Japanese writing on the recent history of journalism in Japan.

Postal agency

Fairly elaborate and extensive road and carrier systems developed wherever the Yamato court and local clans established their authority in what is today Japan. During the Tokugawa period, the system was greatly improved by the need for considerable travel between local domains and the seat of the Tokugawa government in Edo.

On Keio 4-4-21 (11 June 1868), on the eve of the start of the Meiji era, an agency called "Office of stages-and-conveyances" (駅逓司 Ekiteishi) was established to nationalize local components of the "stages-and-conveyance" system, which consisted of a network of facilities and stables for the people and horses that conveyed messages and packages from one stage or post town to the next.

Coinage of the term 郵便 (yōbin), still the standard word for "post" and "postal" in Japanese, is attributed to Maejima Hisoka (前島密 1835-1919), who was instrumental, with Sugiura Yuzuru (杉浦譲 1835-1877), in inaugurating a new nationwide postal system on Meiji 4-3-1 (20 April 1871).

From the 8th month of Meiji 4 (Septemberish 1871), the name of the agency was changed to "Stages-and-conveyances agency" (駅逓寮 Ekiteiryō), which reflected an elevation in its status as part of the Ministry of Finance (大蔵省).

Placed under the Ministry of Internal [Domestic] Affairs (内務省) in 1874, the agency became the "Bureau of stages-and-conveyances" (駅逓局 Ekiteikyoku) in 1877 when 寮 were designated 局. Then in 1881 it became part of the Ministry of Agricultural and Commercial Affairs (農商務省).

In 1885, the "Ministry of posts [conveyances] and communications" (逓信省 Teishinshō) was formed by merging four bureaus, including the 駅逓局 (stage [overland] conveyance bureau) and 電信局 (electric [transmitted] messaging bureau), from which the new ministry derived its name. This ministry became the "Ministry of Transport and Communication" (運輸通信省) in 1943.

Multiple reshufflings of government agencies after World War II resulted in a number of organizational and name changes. The Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications (郵政省), as it was known from 1949, was merged into the Ministry of Public Management, Home Affairs, Posts and Telecommunications in 2001. This ministry became the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications in 2004 when the postal system was privatized.

Newspaper

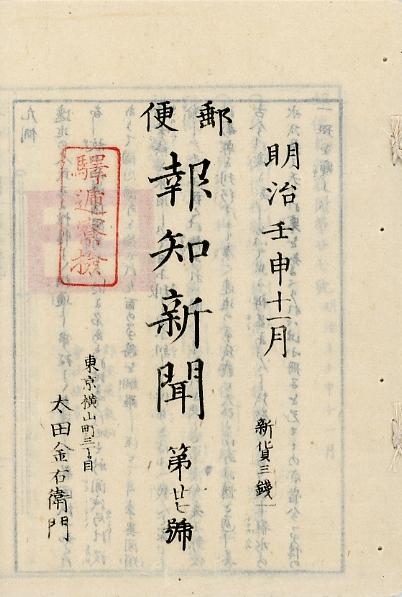

Yūbin hōchi shinbun or "Postal distpatch news" began as woodblock-printed, string-bound news pamphlet in 1872. The Hōchisha (報知社) company was set up in 1873.

The paper was founded and first edited by Konishi Gikei (小西義敬) with the backing of Maejima Hisoka (前島密 1835-1919), and first published by Ōta Kin'emon (太田金右衛門). Konishi became the first president of Hōchisha (報知社), the company set up to continue publishing the paper from 1873.

James Huffman describes its founding like this (pages 53-54 and 416, in Huffman 1997, which see in the Bibliography of this website for full particulars and a review).

|

A final example of the press' early reliance on official initiative was the Yubin Hochi Shimbun, which would stand near the forefront of Tokyo journalism throughout the entire Meiji era. Launched on June 10, 1872, Hōchi's very name, "Postal Reports," suggested its ties to officialdom. The reality was that Maejima Hisoka, minister of posts and telecommunications and the father of Japan's new postal system, had his own personal secretary start the paper. As Kishida Ginkō (who became a writer at rival Nichi Nichi that same year) recalled it, "Maejima was an old friend of mine who would talk repeatedly, in a bookstore we knew, about the need for a newspaper. Finally, he decided to publish one." [Note 40] Maejima's particular dream was to accelerate the process of nation building by having mail handlers all across Japan send news items to the capital for dissemination through a newspaper. So he persuaded his secretary, Konishi Gikei, to assume the editorship and Ōta Kin'emon, a friend who ran a bookstore, to become publisher. He also helped Hōchi cultivate a national network of writers by allowing it to send and receive manuscripts postage-free. [Note 41] And in the process, Maejima secured for yet another government office not only a special pipieline to the public but, of even greater importance to him, a way to spread modern ideas more quickly. [Note 42]. Note 40 Kishida Ginkō, "Shimbun jitsureki dan," in Tsurumi Shunsuke, ed., Jiyānarizumu no shisō, p. 66. [Kishida Ginkō, "Shimbun jitsureki dan" (Talk about my newspaper career). In Tsurumi Shunsuke, pp. 63-66. Tsurumi Shunsuke, ed. Jiyānarizumu no shisō (Philosophy of the press). Vol. 12 of Gendai Nihon shisō taikei (Comprehensive outline of modern Japanese thought), ed. Matsumoto Sannosuke. Chikuma Shobō, 1965.] Note 41 Free postal delivery of newspaper manuscripts was extended to other newspapers July 1, 1873; see Sugiura, p. 213. [Sugiura Tadashi. Shimbun koto hajime (Newspaper beginnings). Mainichi Shimbunsha, 1971.] Note 42 See Chikamori Haruyoshi, Jinbutsu Nihon Shimbun shi, p. 88; Albert Altman, "The Emergence of the Press in Meiji Japan," pp. 120-121; Uchikawa Yoshimi, Shimbun shi wa, p. 143. [Detailed references omitted here]. |

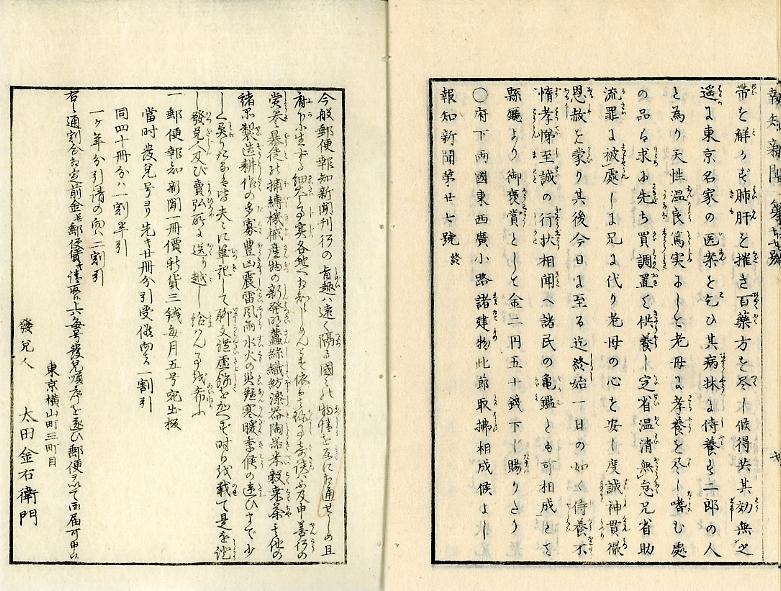

The cover date of the first issue of Yū hōchi shinbun is 明治壬申六月 (Meiji Jinshin-nen 6-gatsu), a sexagenary date corresponding to Meiji 5-6, a lunar month. Apparently this issue came out on Meiji 5-6-10 (1872-7-15). (Machida 1986:36)

This and other early issues were published as woodblock pamphlets by Ōta Kin'emon until the founding of the company Hōchisha the following year. "Yūbin" was dropped from the name of the paper from the 1894-12-26 issue.

See Yubin hochi shinbun in the Almanac section of this website for details about the somewhat "puncuated" evolution of the paper into today's nationally distributed Supootsu hōchi (Sports dispatches).

Wood to metal

The early pamphlets (sasshi) were produced with hanshiban paper which, when folded, was about 15.5 by 22.5 centimeters (6 by 9 inches) -- roughly the size of a large digest.

Some earlier editions are also found on slighly smaller paper measuring, when folded, 14.5 by 21.0 centimeters (5-3/4 by 8-1/4 inches). The printing, however, is of the same size as that on the larger sheets. Moreover, the paper sizes are proportional. Hence the smaller pamphlets differ in size only with respect to their proportionally smaller margins on the top, bottom, and right (binding) edges.

Yosha Bunko has two copies of Number 27, one larger, the other smaller, and mixed sizes of a few other issues. All the smaller copies appear to be fresher, and though they seem to have been printed from the same blocks, they may be facsimilies.

Woodblock pamphlets (weekly)

Number 1 was published on Meiji 5-6-10 (1872-7-15) in the form of a woodblock-printed pamphlet (冊子型木版刷). Five issues were published every month, which meant about one issue a week.

See Numbers 11, 27, and 39 below.

Metal-type pamphlets (weekly)

By May the following year, the numbered folios between the covers of the news pamphlet were being printed with metal type (冊子型活版刷). The covers, however, continued to be printed with woodblocks.

See Numbers 51 and 53 below.

Pamphlet to broadsheet

Most of the early pamphlets had 9 leaves of washi (mulberry paper) printed on one side only, then folded into folios that were bound on the right. Since two of the leaves served as covers, the body of the pamphlet consisted of 14 pages numbered as leaves 1 to 7. Some issues exceptionally had a few more leaves.

Metal-type-printed broadsheet (daily)

From sometime early in June 1873 -- 6 June according to one source -- Yūbin hōchi shinbun began to be published as a daily. The change in frequency of publication came with a change in the manner of printing, format, and pagination. These changes resulted in a significant increase in the amount of information published.

Size

The new format consisted of a single sheet of washi printed with metal type, two pages on each side, which was then folded to make a four-page brochure. When closed, the newspaper was 24.2 x 34.7 centimeters (9-1/2 by 13-2/3 inches) -- comparable to a B4 sheet of paper today. It opened to 48.4 by 34.7 centimeters -- or about B3 size.

Broadsheet papers today are printed on rolled paper which, coming off the press, is cut to A1 sheets that fold to make four A2 pages.

Information

In terms of page size, the broadsheet edition was about twice the size of pamphlet edition. Thus one page in the broadsheet was equivalent to two pages (one folio) in the pamphlet edition.

In terms of total page area, then, one issue of the four-page broadsheet was tantamount to 4/7ths of the 7-folio (14-page) pamphlet.

Typographically, the character density of the metal-type broadsheets remained the same as that of metal-type pamphlets. The same number of characters in a column, and the same number of columns in a row, did not change. Hence the broadsheet published, everyday, 4/7ths of the information the pamphlet had published once a week.

The change in frequency and format meant that Hochisha had begun to publish about three times more information a week.

Heavier washi

The washi used for the folios of the pamphlet edition was of a rather thin and fibrous stock. The copy of Number 63 in Yosha Bunko is printed on a thicker stock, similar in weight to but less fibrous than the paper used for most contemporary nishikie.

The size of new format, after folding, was also essentially the same as that of most nishikie printed in Edo and Tokyo, with vary within a centimeter or so in both directions.

See Number 63 below.

Particulars

The information on the cover, masthead, or colophon, and in the publisher's statement, reflect changes in the character of the newspaper during its early months and years.

Cover

Vermilion approval stamp

The covers of all pamphlet issues have a vermilion stamp in the upper left corner with four graphs indicating that the newspaper had been approved by the government.

驛逓寮檢

Ekiteiryō ken

Approved by Stages-and-conveyances Agency

Black price box

The covers of the pamphlet issues show the following price in a box in the lower right corner.

新貨三錢

Shinkwa san-sen (Shinka 3-sen)

New money 3-sen

The term "new money" refers to the "New money ordinance" (新貨條例 Shinka jōrei), Great Council of State Proclamation No. 267 of Meiji 4-5-10 (27 June 1871). This law adopted the yen (圓、円) as the principal unit of Japanese currency, with subunits of sen (錢、銭 100 sen = 1 yen) and rin (厘 10 rin = 1 sen).

Revised numerous times over the next several years, the new money ordinance was revised and renamed as the "Currency ordinance" (貨幣條例 Kahei jōrei) by GCS Proclamation No. 108 of Meiji 8-6-25 (1875-6-25). This ordinance was replaced by the "Currency law" (貨幣法 Kaheihō), sealed on 26 March 1897, promulgated as a Law No. 16 on 29 March, enforced from 1 October.

Publisher's name and address

The covers of Numbers 27 and 39 show the publisher's address and name in the lower left corner.

東京横山町三丁目

太田金右衛門

Tōkyō Yokoyamachō 3-chōme

Ōta Kin'emon

This information is repeated, with more information about pricing and subscritions, on the inside of the back cover, in what amounts to a colophon. No company name is shown on either on the cover or the colophon.

On the colophon, Ōta is described as a 發兌人 (hatsudanin), a person who printed and distributed printed matter. Today the colophons of most publications identify the "publisher" as either 発行所 (hakkōsho) or 発行人 (hakkōnin), referring to respectively the company or the person.

Numbers 51 and 53 show only the name of the company on their cover and colophon, as follows.

報知社

Hōchisha

Guide

A 凣例 (凡例 reibon) is printed on the inside of the unnumbered front cover folio. The content of this "guide" or "explanation" or "legend" amounts to a "mission statement". The statement begins with the phrase "people near and far" (遠近の人民 enkin [ochikochi] no jinmin) and refers to the "news paper" (新聞紙 shinbunshi) as the means by which information is to be mutually conveyed.

Note that, at the time, "shinbun" (新聞) and "shinbunshi" (新聞紙) were clearly differentiated, the former meaning "news" and the latter meaning "newspaper" or "paper" publication conveying "news".

Graphically there was also 新聞誌 (shinbunshi), which meant "news journal". This had been original title of the Japanese-language news pamphlet published in Yokohama by Joseph Heco (Hamada Hikozō). The first issue is dated Genji 1-6-28 (31 July 1864). The name changed to 海外新聞 (Kaigai shinbun) or "Overseas news" from the third month of the following year (circa April 1865), and the paper continued to be published until about Keiō 2-10 (circa November 1866). "Kaigai shinbun" was widely use as a term for "overseas" or "foreign" news (Machida 1986:18, 22, and Waseda 1987:26) .

The term 雑誌 (zasshi), used today for magazine, means "miscellany journal". The term 新聞雑誌 (shinbun zasshi) was used both as the title of a newspaper and in reference to news pamphlets or magazines.

Some of the content of from early issues of Charles Rickerby's "The Japan Times", published in Yokohama from Keiō 1-8 (circa September-October 1865), were translated in the form of a news pamphlet called 日本新聞 (Nihon shinbun) or 日本新聞書 (Nihon shinbun sho), meaning "Japan news" or "Japan news writings". In 1918, a later incarnation of this paper joined an earlier incarnation of today's "The Japan Times", which began in 1897.

Colophon

Publishing particulars, including subscription rates and the address and name of the publisher, are printed on the inside of the unnumbered back cover folio.

The price of one booklet (一冊) of Yūbin hōchi was stated (as it was on the cover) to be 3-sen in New Currency. Five issues would be published every month. Five issues, taken from the current issue, would be discounted 10 percent. Forty issues would be discounted 15 percent. A one-year subscription would be discounted 20 percent.

Supplements

"Number 51 Supplement" has neither an explanation nor a colophon, hence the insides of the front and back covers are blank. I have not yet been able to establish whether this is a standalone issue, or whether it is a supplement to an issue marked only "Number 51".

Language

The reportage was fairly succinct, and anyone with a basic education could have read it. Most of the articles could also be read by a person of average literacy today, once the person made a few adjustments to the older script, orthography, usage, and grammar.

Furigana

In articles written by Hochi reporters, most of the kanji expressions showed their pronunciation in furigana to the right of the graphs. Over the following decades, furigana became standard in popular newspapers and magazines. The practically universal use of furigana or "rubi" in popular publications continued for a number of years following language reforms after World War II.

The reduction of the number of kanji in standard use, the greater use of hiragana to write what used to be written in kanji, and increase in average years of literacy education, resulted in the abandonment of furigana as a matter of course in mainstream newspapers and magazines. Today rubi are routinely used only in children's books and some manga, a few newspapers and magazines aimed at readers who are likely to be less literate, and official pamphlets with information intended for a wide range of readers.

Double furigana

Some kanji expressions had furigana on both sides, the pronunciation on the right, the meaning on the left. In such cases, the furigana on the right is usually a Sino-Japanese but sometimes an English or other foreign-langauge (including Chinese) reading, while the furigana on the left is a Japanese reading.

In the following transcriptions, I have shown the primary (right) furigana first, and the secondary (left) furigana second and underscored, like this.

和牛わぎう にほんうし・・・牛肉ぎうにく

Wagyū (Nihon ushi) ・・・gyūniku

Yamato steers (Japan cattle)・・・steer-meat [beef]

Kanbun and sorobun

Inevitably there was some -- but not much -- kanbun or sorobun phrasing in newspaper articles.

Kanbun or "Chinese writing" was originally Chinese but, over the centuries, had evolved into a written language in its own right -- at once a Japanized form of Chinese and a Sinified form of Japanese. Kanbun continued to be fairly common well into the Meiji period in the writing of philosophical and other serious tracts, but was also used in the writing of some reportage and fiction.

Sorobun or "soro writing" was a kanbunesque or very hybrid form of Japanese. It remained the standard for issuing proclamations and other laws and regulations during the early years of the Meiji period. Sorobun was called such because it used the graph 候 (sōrō) to represent the many combining forms of "de aru" and "aru" and "suru" in conjunction with other graphs.

Sorobun writing could use any degree of kana with kanji, from none to a lot. Sorobon texts using kanji to represent kana can be mistaken for true kanbun style. But a sorobun text could also contain true kanbun phrasing, which was often the case when writing proclamations.

Sorobun in newspaper reports

Newspaper articles, when reporting the issuing of a new law or regulation, either directly cited or closely paraphrased the proclamation or directive. Two examples of such reports are shown below, one concerning the prohibition of begging for alms by monks (Hochi 27), the other concerning the report of a fire in the Chinese residential area of Nagasaki (Hochi 39).

In both examples, some of the key words in the sorobun texts are marked with furigana. In one example (Hochi 27), a kanbun phrase is marked with kaeriten. Such markings were intended to make the article more readable for those who might be less literate, or whose literacy had been conditioned by the use of furigana and kaeriten in instructional materials.

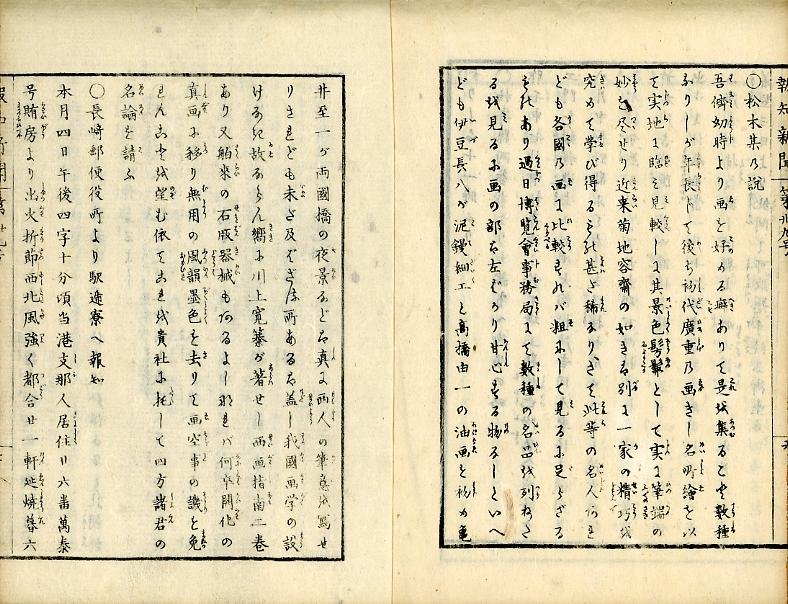

Hochi Number 11

|

Number 11, typical of the the early 7-folio, 14-page woodblock editions of Yūbin hōchi shinbun, is full of all manner of articles, including a report on Arima Yoshishige (1828-1881), the last daimyo of Kurme domain in Chikugo province (1841-1871), and two articles on devasting typhoons, in addition to official matters and human interest stories.

Of particular interest here are the following two articles, one touching upon the importance of science to a country's strength and prosperity, the other about newspapers.

The copy in Yosha Bunko is of the standard 15.5 by 22.5 cm size. Publisher's remarks and particulars are woodblock printed inside front and back covers.

Country, people, minds, science

A two-page article titled "Abridgment of someone's western-ocean tales" -- which ends with a remark about the "wealth and strength of the country" (國の富強 kuni no fukyō) -- begins like this (page 3a, see image below).

|

某人西洋物語略 國の強盛きょうせい つよくさかんハ人民に由より人民の強盛ハ心に由り心の強盛ハ窮理きうりを知るに由る Abridgment of a certain person's western-ocean tales The power [strength and prosperity] of a country is due to its people, the power of its people is due to their minds [hearts, spirits], and the power of their minds is due to knowing science [reach reaon]. |

KRS version of first line in Hochi article

The above line, at the start of the Hochi article, may have been inspired by the following line from a 1858-1861 publication called Kanpan / Rikugō sōdan, which I am calling KRS. The line comes at beginning of a statement cited by Iwata Takaaki in his study of KRS (Iwata 2009:135, my translation).

|

国の強盛は民に由り,民の強盛は心に由り,心の強盛は格物に由る。 The power [strength and prosperity] of a country is due to its affiliates, the power of its affiliates is due to their minds [hearts, spirits], and the power of their minds is due to investigating-things [and arriving at knowledge] [science]. |

Iwata attributes the statement, which begins with the above sentence and expands on its three elements, not to the original KRS text, which is written in Chinese, but to a Japanese translation by Fujii Shōzō in Nihon shoki shinbun zenshō (日本初期新聞全集), published by Perikansha (ペリカン社) in 1986 (Iwata 2009:133, note 18).

Iwata further attributes the statement to the "On investigating matters and exploring their principles" (格物窮理論) section in Volume 6 of Kanpan / Rikugō sōdan (官板 / 六合叢談) or "Official publication / Collected stories of everything in the six directions" -- a Tokugawa government edition of a Chinese-language periodical published from 1857-1858 by the Shanghai branch of the London Missionary Press, of the London Missionary Society (Iwata 2009:130).

KRS version of first line in Hochi article

As published in China, the periodical's name was 六合叢談 (Liu-ho ts'ung-t'an, Liù4hé cóngtán) -- "Collected stories (叢談) about [everything in the] meeting of [all] six [directions] (六合)" -- i.e, stories about everything above and below, and east, west, south, and north -- to wit, everything in the universe, the knowable world, everywhere. The title of the Japanese edition is preceded by 官板 (Kanpan), meaning "Official [Government] publication".

The Japanese edition -- which I am calling KRS (Kanpan Rikugō sōdan) -- was published from 1858-1861. Articles related to Christianity, and articles concerning the lunar calendar and the price of traded commodities, were deleted. Other articles were printed as received, in Chinese, which was "translated" into Japanese by inserting kaeriten on the left to show the order in which the graphs were to be read (Iwata 2009, page 130, and see Sources below).

Iwata observes that KRS was originally published in 15 pamphlets (冊), which were later published in the form of 6 combined-pamphlet (合冊) volumes -- by which he seems to mean 6 volumes (巻).

Waseda University Library's Kotenseki Sogo Database has high-resultion scans of Volumes 1-4 of the later bound edition. These volumes show that the original "translation" included not only kaeriten, but also markings on the right of the graphs, of the kind commonly found in kanbun texts, namely (1) post-positions to clarify the Japanese phrasing, (2) some (but very little) okurigana to clarify conjugations, and (3) some (but practically no) furigana to facilitate reading especially proper nouns.

According to Iwata, the date of the issue of the Chinese edition of Rikugō sōdan in which the statement he cited appeared was 咸豊丁巳閏五月朔日, or the 1st day of the 5th intercalary month of the Teishi (Tingssu, Dingsi) or 7th year of Kanhō (Hsienfeng, Xianfeng) -- equivalent to Ansei 4-i5-1 on Japan's reign-year calendar -- or 22 June 1857 in Gregorian terms.

Editor of Liu-ho ts'ung-t'an

According to Iwata, 六合叢談 (Liu-ho ts'ung-t'an, Liù4hé cóngtán) was published under the editorial superintendency of Alexander Wylie (1815-1887), a missionary known in China as 偉烈亜力 (Iwata 2009:130).

Masuda Wataru (増田渉 1903-1977), a student and translator of Chinese literature who had studied in Shanghai under Lu Xun (魯迅 Lu Hsun, 1881-1936), who himself had studied in Japan, also states that "the Shanghai serial edited from 1857 by Alexander Wylie, Liuhe congtan (Stories from Around the World), was being reprinted with reader punctuation in Japan" (Masuda 2000, page 13, see Sources below). Masuda's personal collection included "the reprint edition of Liuhe congtan (volumes 1-13)" and other contemporary publications.

Waseda University Library attributes the 1857-1858 Chinese periodical to William Muirhead (1822-1900), also a member of the society and one of the founders of the press. It appears, though, that Wylie, a student of both European and Chinese math and science, oversaw the publication of Liu-ho ts'ung-t'an.

Newspaper history

Hochi Number 11 ends with an interesting two-page report from Nagasaki about news and newspapers. The report begins like this (page 7a).

|

長崎表服部某より来書 昔者羅馬らうば人の用ひなる日報は頗すこぶる今の新聞紙と彷彿ほうふつ さもにたりせり然して英國いぎりすにては「ヘンリ」第六世の時に當り新聞記載の書付始めて行れたり米國あめりかにては千七百七年我宝 / 永四 / 丁亥「ボストン」にて始めて行れたり・・・ Correspondence from a certain Hattori in Nagasaki The daily reports used by Romans in the past were very similar to (closely resembled) the newspapers of now. And in England at the time of "Henry" 6th bills of news articles first were effected. In America in 1707 (Our Hōei 4 Teigai) "Boston" [bills of news articles] first were effected. . . . |

And on and on . . . using the same "first were effected" formula . . . France (佛國) in 1631 (Our Kan'ei year Shinbi), Germany (日耳曼ぜるマん) in 1615 (Our Genna gan (1) Itsubō) . . . and by 1862 (Around our Bukyū 2 Jinjutsu) in all part of English territory . . . and now also in Our Imperial Country -- a vertiable history of the spread of news publications, all this by way of leading up to a plug, at the end, for Yūbin hōchi shinbun as the means of disseminating news gatherered through the good offices of the Stages-and-conveyances Ministry.

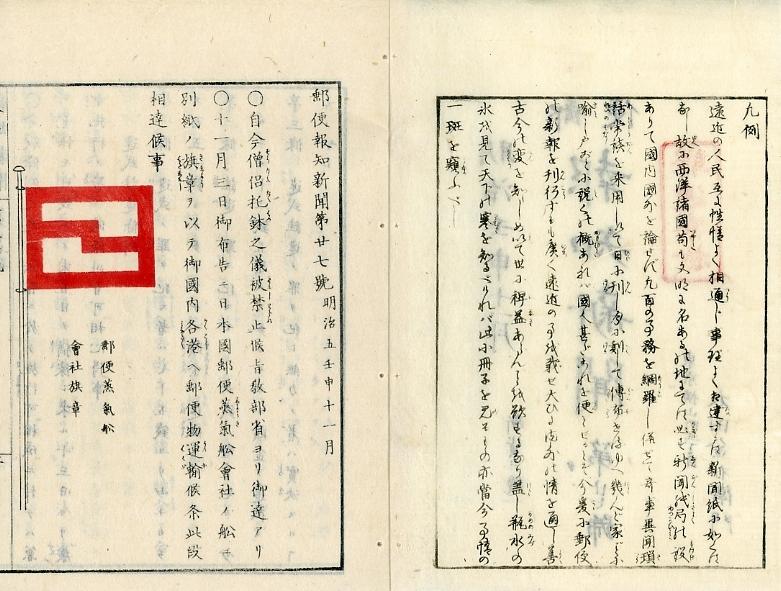

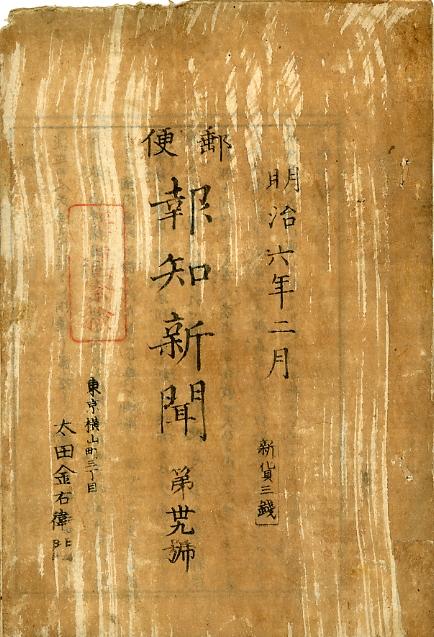

Hochi Number 27

|

Practically the entire issue of Number 27 was given to the 53 articles of the Tokyo prefecture ordinance. The ordinance filled nearly ten pages (1b-6a) of what was then a 7-folio, 14-page news pamphlet published about five times a month.

There were at least two printings, apparently made from the same blocks, but on different sizes of paper. The larger and presumably original printing is approximately 15.5 x 22.7 cm folded. The smaller and presumably later printing, possibly a facsimile, is 14.5 x 21.1 cm. Yosha Bunko has copies of both issues.

The following images are of the smaller copy, as it was in better condition. For images of the cover and first page of the larger, presumably original copy, see News nishikie: An arranged marriage that didn't last on this website.

The date on the cover is shown as 明治壬申年十一月 (Meiji Jinshin-nen 11-gatsu), a sexagenary cycle version of Meiji 5-11, or about December 1872.

The issue is woodblock printed in 7 numbered folio between cover folios, and the inside pages of the covers include a guide (front) and colophon (back).

Number 27 is noted for its image of the red flag of the Postal Steamship Company. It is most important, however, as one of the earliest disseminations of Tokyo prefecture's Ishiki kaii jorei (違式詿違条例) immediately after its promulgation the same month. See this link for for scans of the entire issue and more details about the 1872 ordinance.

Begging for alms prohibited

Number 27 leads, though, with the following brief on the recent prohibition of begging for alms by monks. The text is transcribed as received, with furigana and kaeriten shown as subscript following related kanji.

Because I want to comment on the language in which the article is written, I have romanized the transcription, showing how I suspect it would have been read aloud. The translation is my usual attempt to reveal phrasing and metaphors of the original text (page 1a, see image below).

|

Transcription showing furigana 自今僧侶そうりよ托鉢たくはち之儀被禁止きんしさられ候旨教部省ヨリ御達アリ Transcription showing kaeriten 自今僧侶托鉢之儀被一禁止二候旨教部省ヨリ御達アリ Transliteration Ima yori souriyo (> sōryo) [no] takuhatsu no gi (> no koto) [wa] kinshi sarare sōrō mune (> sararemasu koto), Keubushiyau (> Kyōbushō) yori o-tasshi ari Translation There is a circular from the Ministry of Instruction purporting that, From now [begging for alms with] palm bowls [by] monks is prohibited. |

The above article consists of a single sentence -- a conventional non-sorobun sentence in which the writer has embedded, by way of paraphrasing if not directly citing, a government notification written in highly Sinific (kanbunesque) sōrō-bun style.

The phrase 被禁止 is a Chinese passive. The furigana attached to the phrase, however, is a Japanese passive. The furigana show the effects of the two kaeriten, which tell the reader to take the meanings of 禁止 first and 被 second -- i.e., "kinshi" plus "sarareru" -- the passive form of the verb "su" or "suru" meaning "to do" -- hence "kinshi sarareru" meaning "to be prohibited". The furigana show the conjunctive form "sarare-" to which one then adds "-sōrō" or "-masu" or whatever, depending on how one wishes or needs to read 候.

Ministry of Teachings Order No. 25 of Meiji 5-11-9

The printed version in Hōrei zensho, however, transcribes like this (HRZS 7, Volume 7, Meiji 5, page 1286).

|

[ 教部省] 第二十五號(十一月九日) [ Ministry of Teachings ] Number 25 (11 month 9 day) |

Note that, as promulgated on lunar Meiji 5-11-9 (solar 9 December 1872), the order is written in active voice, or that of the issuing authority. The version embedded in the Hochi article has been rendered in passive voice because the newspaper is merely reporting, not dictating, the law.

I have not seen a copy of the original notification, but I suspect that, like the HRZS version, it has no furigana. The Hochi version shows furigana only for the key words -- which alone might be read "sōryo [no] takuhatsu [wa] kinshi sarare- [-ru]" -- which clearly conveys the gist of the order.

Ministry of Teachings

The 1872 prohibition of begging for alms came at a time when Buddhist institutions and practioners were coming under considerable pressure, even oppression, from Shinto interests in both government and private sectors in many parts of the country.

Earlier in 1872, the Ministry of [religious] Teachings (教部省 Kyōbushō) had been established under the Council of State, replacing the Ministry of [Shintō] Rites (神祇省 Jingishō). The new ministry oversaw the Office of Instruction (教導職 Kyōdōshoku), and managed matters related to Shintō and Buddhist doctrines, shrines and temples, and [imperial] mausoleums and graves. In 1877, however, it was incorporated into the Bureau of Shrines and Temples (社寺局 Shajikyoku) in the Ministry of Interior Affairs (内務省 Naimushō).

On 15 August 1881, the Interior Affairs Ministry fired off a volley of circulars that permitted begging by monks under certain conditions.

Kō No. 8, refering to and citing Ministry of Teachings Order No. 25 of 1872, abrogated (廃) the prohibition (禁止), and stipulated in a proviso that a person begging for alms (托鉢者) would have to carry a permit issued by the chief abbot of a sect (管長). (HRZS Volume 16, Meiji 14, page 376)

Otsu No. 38, referring to Bo No. 8, stipulated how abbots of a Shintō and Buddhist sects were to oversee devotees who would beg for alms (HRZS Volume 16, Meiji 14, page 439)

Bo No. 2, referring to Kō No. 8 as having "lifted the ban" (解禁) on begging for alms, detailed the procedures for obtaining a begging permit, and the particulars that were to be written on the front and back of the wooden tag that an alms begger was to carry. The circular also forbade begging that would constitute a nuisance, such as trespassing on private property or obstructing public thoroughfares, or moving in groups of more than three to ten in a file. (HRZS Volume 16, Meiji 14, pages 460-461)

Many interesting observations on motives behind the control of begging by itinerant monks can be found in Ian Reader's Making Pilgrimages: Meaning and Practice in Shikoku (Honolulu: Hawai'i University Press, 2006). Reader's book, though not specifically about the above notices, does refer to the 1872 ban and its 1881 rescindment (pages 140-141).

Tokyo's regulations on public behavior

See Ishiki kaii jorei (違式詿違条例) for scans of the entire issue of Hochi Number 27, and for more details about this important late-1872 ordinance, which set standards for the policing of public behavior throughout the country.

Hochi Number 39

|

Number 39 shows a cover date of 明治六年二月 (Meiji 6-2), presumably a solar date, hence equivalent to February 1873, as Japan had just adopted the solar calendar by equating Meiji 6-1-1 to 1 January 1873.

This issue, too, has 7 numbered folios, with a guide and colophon inside the front and back cover folios.

There are articles on the service of imperial guards, a dispatch from Aomori prefecture, opinions by a certain Yamamoto and a certain Matsumoto, among other articles -- and of special interest here the following two pieces.

Of special interest here is a short article about a fire in Nagasaki's Chinatown, and a brief about the posting of an official to Chosen.

Nagasaki Chinatown fire

A four-line report from the Nagasaki post office concerns in a Chinese residential area. The heading of the report disloses only its source.

|

長崎郵便役所より駅逓寮へ報知 本月四日午後四字十分頃当港支那しな人居住きよじう廿六番萬泰号賄房くわいばう まちあひべやより出火しゆつくわ折節おりせつ西北にしきた風かぜ強つよく都合つごう廿一軒延焼えんしよう暮くれ六時過すぎ鎮火ちんくわいたし候此旨御地在留ざいりう支那人しなじん共へ御布達有之度此段申上候 Dispatch from Nagasaki Post Office to Stages-and-conveyances Agency About 4 hours and 10 minutes after noon on the 4th day of this month, in this port, from the waiting room of the Mantaigō [House of Myriad Prosperities], in 26-ban, where is a residence of China people, a fire broke out, and at times the northwest wind was strong, and [the fire] spread to and burned, in all 20 buildings, and in the evening past the hour of six [firemen] quelled the fire. We [hereby] relate [this to you], desirous that that there will be your proclamation of [hoping that you will kindly convey] the purport of this to the China people residing in your location. |

The terms "Post" (郵便 yōbin) and "Stages-and-conveyances Agency" (駅逓寮 Ekiteiryō) have been discussed above in the section on the founding and development of the postal agency.

"4:10" is written 四字十分. The graph 字 (ji) was commonly used at time as shorthand for 時 (ji) meaning "hour".

Two instances of 候 (sōrō > masu) are written with a reduced graph that looks like レト. Both instances mark the end of a sentence, hence the terminal punctuation in the translation.

The name 萬泰號 (万泰号 C. Wàntài-hào, J. Mantai-gō) means something like "House of Myriad-prosperities". At the time, the lot on which a building in a certain "area number" (番 ban) was referred to by the "name" (号 gō) of the building, according to the formula "area-number + building-name" (○○番○○号 or ○○-ban ○○-gō).

"Wàn Tài Hào (萬泰號, 萬泰号, 万泰号) is fairly commonly found today as the name of a hotel or other business in both the Republic of China (ROC) and the People's Republic of China (PRC). It is also found in Japan, and in fact is still alive and well in Nagasaki's Chinatown.

On the southwest corner of the first block east of the main intersection of Nagasaki's Chinatown is a noodle maker called 萬泰號 on maps. The address is 新地町13番17号 or "Shinchimachi 13-ban 17-gō".

"Shinchimachi (新地町) is a synonym for Nagasaki's Chinatown. The name, literally "new-land-town", goes back to the years following 1859, when the port of Nagasaki was opened to foreign ships and commerce under treaties Japan had signed with the United States and some other countries. The "new land" or "shinchi" (新地), though, goes back to the turn of the 17th and 18th centuries.

Nagasaki chanpon

A website featuring a chronology of the history of ramen (ラーメン raamen, 拉麺 lāmiàn) in Japan from 1584-1976 shows the following statement for 1897 (my translation, 25 February 2010).

|

1897 The proprietor of 'Mantaigō' (萬泰号 C. Wàntài-hào), Mr. Rin (林 C. Lin), migrated from Shanghai and opened a sundry foodshop. He handled t!aku (唐灰 トウアク), and after the war started producing kansui (カンスイ), and making noodles (麺 J. men, C. miàn), and exists now. (Nagasaki) |

"Kansui" is an alkali used for making ramen noodles. It consists of sodium carbonate, potassium carbinate, and sodium and calcium salts of phosphoric acid, and is prepared from mainly potassium carbinate with some sodium bicarbonate, potassium carbinate, and calcium phosphate.

"Men" noodles in Japan, whether associated with Fujian (Fukien) province or with Taiwan, or with Okinawa or Nagasaki, are generally called "raamen". So-called "Okinawa soba" has a history of half a millennium.

While "tōaku" continues to be used in the making of Nagasaki Chanpon noodles, JIS food standards permit only the more general term "kansui" on labels.

Nagasaki Chanpon is a noodle dish made by cooking noodles, made specially for this manner of preparation, in a soup made from boiling chicken and pork bones, after the soup has been added to a pan in which pork, seafood, and vegetables have been fried in lard. Unlike other ramen dishes, its preparation requires only one pan.

A Nagasaki prefectural ordinance permits the use of "Chinese ash" (唐灰 tōaku, tōwaku) in the prefecture only in the making of Chanpon noodles. It's manufacturing and use is controlled because postassium carbonate, as chemists would call it, is regarded as a pharmaceutical substance. Other kinds of ramen noodles are made with "kansui" (かん水 < 鹹水, 梘水, 漢水 etc), an alkaline water.

Chemically, "kan" is an alkali composed mainly of potassium carbonate with some sodium carbonate and various phosphates. Ramen can be made with the "kansui" or alkaline water of certain lakes. Otherwise it is prepared by making acqueous solutions of ashes having suitable alkaline properities. Such ashes are manufactured from certain plants for specific use in the making of ramen. Only a few people are licensed to make the ashes and their aqueous solutions for ramen.

Ramen dough is prepared by mixing wheat flour with ordinary water, kansui, and salt. The dough of Nagasaki chanpon noodles , though, uses a special kind of kansui called 唐灰汁 (tōaku, tōwaku), which means "Chinese ash-soup". The graphs 灰汁 are read "aku" and refer to the "lye" made from the ashes of certain plans or the alkaline soup or scum that results from the boiling of some vegetables, made to make certain kinds of soaps or detergents. The expression is sometimes graphed 唐灰水 but is most commonly written just 唐灰.

China trade

Trade began with Portugaese ships in 1550 and Spanish ships in 1584. Holland and England establish trading facilities on Hirado in 1609 and 1613.

During the 1630s, an Dejima, an artificial island, was built for the Portuguese trade in the bay of the town of Nagasaki. The Shimabara rebellion in the late 1630s, following bans on Christianity, however, resulted in Japan severing its ties with all European countries except Holland, and by 1641, Dutch vessels and personnel had been relocated to Dejima.

Trade with Chosen, disturbed by Hideyoshi's failed invasions of the peninsula in the late 1590s, continued through the island of Tsushima, between the Korean peninsula and the mainland of Kyushu. During the Tokugawa period, Tsushima was site of most diplomatic exhanges between Japan and Korea.

Once a province in its own right, by the Tokugawa period Tsushima had come under the control of a clan on the Kyushu mainland. The clan monopolized trade with Chosen and represented Japan in its diplomatic exchanges with Chosen. As such Tsushima was also referred to as Tsushima-Fuchū province.

In 1871 and 1872, Tsushima was briefly part of two prefectures that no longer exist then part of Saga prefecture. Later in 1872, however, it was affiliated with Nagasaki prefecture.

During the Tokugawa period, indirect trade with China took place between the Ryukyu Kingdom, which was then a tributary of China, and the Shimazu clan in Kagoshima province of Kyushu, which had also gained a degree suzerainty over Ryukyu.

Direct trade with Chinese vessels, at one time conducted through Hakata, hear Dazaifu, the diplomatic headquarters of the Yamato Court, had also come to be accommodated at Hirado. But Nagasaki became the official port for Chinese trade too.

Unlike the Dutch, who were isolated on Dejima, Chinese lived in the town of Nagasaki. In 1689, however, some 4,888 Chinese the town and its environs were resettled in a Chinese quarters (唐人屋敷 Yōjin yashiki) built on the coast of the bay a bit to the south of Dejima (ibid., page 176).

The purpose of the Chinese quarters, surrounded by moatlike canals, was to isolate and control Chinese. But unlike Dejima, which was reached by a short bridge over water, the Chinese quarters were part of the mainland. Moreover, local merchants were allowed to come to the entrance of the quarters and directly sell food to its inhabitants (Lee and Nagai 1996, page 176).

In 1698, a fire destroyed nearby warehouses full of cargo from Chinese ships. The following year, part of the bay along the coast of Hamamachi, between the Chinese settlement and Dejima, was filled, and new warehouses were completed on the landfill in 1702. Early maps and photographs show that this facility, called Shinchikura (新地蔵) or Shinkurasho (新地蔵所), was linked by bridges to both the settlement and the mainland.

After Nagasaki became a treaty port, a settlement for foreigners was built and the Chinese quarters were abolished. In 1865, ownership of the "new land" on which the warehouses had been built passed to the government, which integrated the land into the foreign settlement.

From 1869, the bay around the land began to be filled, and resulting area was called Shinchimachi (新地町). In the meantime, Chinese who remained in the area, and those who came after that, settled in Shinchimachi -- hence the location of Nagasaki's Chinatown.

The town of Nagasaki expanded to include the entire area along the bay, and numerous other towns and villages in the area are now part of the city of Nagasaki. Much of the bay along the coast, including Dejima, has been swallowed by the mainland.

The old Chinese quarters, once on the coast, are now located well inland in what is now Kannaimachi (館内町). Nothing remains of the quarters except a few historical markers, a couple of recontructed edifices, and a namesake boulevard. The warehouse area, now part of Shinchimachi, is also several blocks inland of what is now called Dejima Wharf.

Posting of official to Chosen

Immediately following the Nagasaki story is the following one-line report.

|

本月十二日外務省七等出仕廣澤弘信なる●●朝鮮ちよ[餘]うせn國在勤さいきん被一仰付二●るよし On the 12th day of this month Ministry of Outside [Foreign] Affairs 7th-class [civil, government, imperial] servant Hirosawa Hironobu was assigned [appointed] to a post in Chōsen [Korea]. |

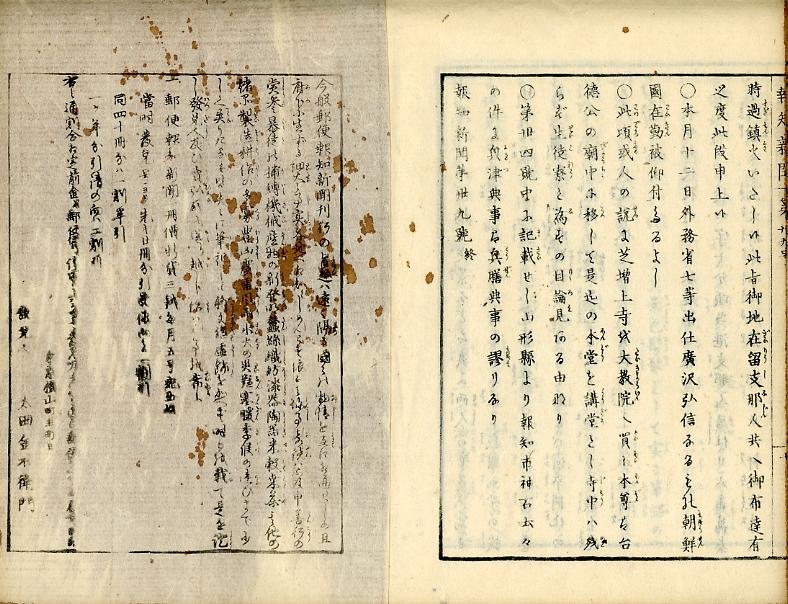

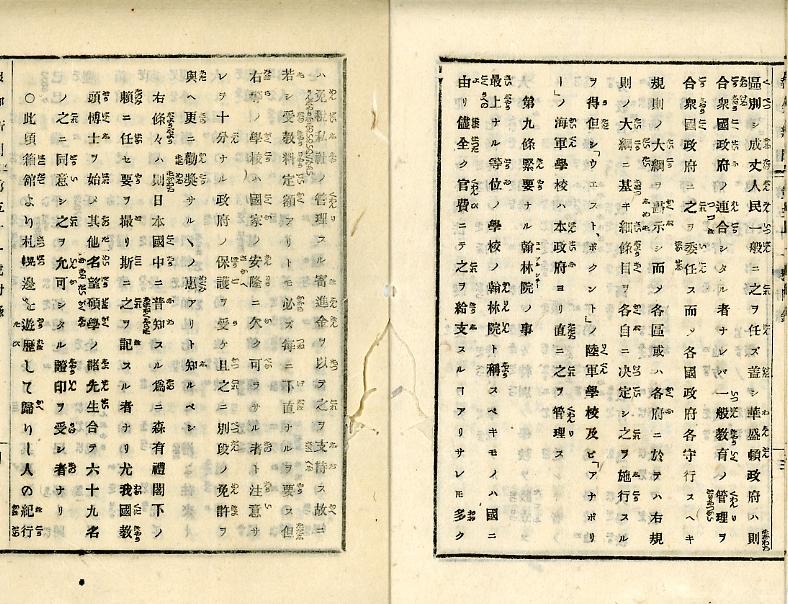

Hochi Number 51 / Supplement

|

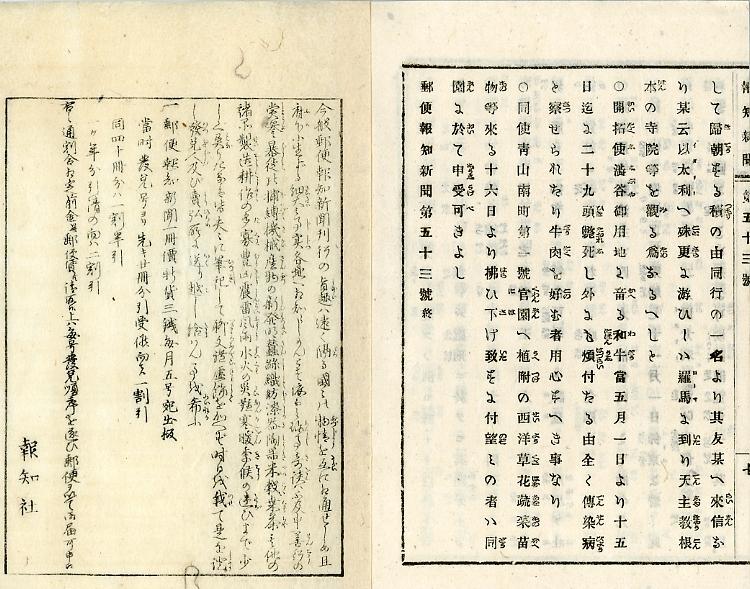

The format of this issue, dated Meiji 6-5 (May 1873), is that of a typical 7-folio pamphlet edition of the paper, except that it is called a "Number 51 / Supplement" (第五十一号 / 附録 Dai-51-gō / Furoku) furoku). The numbered leaves, however, were printed with metal type.

I have not been able to examine the full run of early issues, hence cannot rule out the possibility that this is a standalone irregular issue. However, since it has neither a guide nor a colophon, it may have been distributed with a regular issue called only "Number 51". The copy in Yosha Bunko is of the standard 15.5 by 22.5 cm size.

The main feature of the supplement appears to be its article featuring American school regulations sent to the Ministry of Exterior [Foreign] Affairs by Mori Arinori, Japan's charge d'affaires in Washington.

Mori Arinori and American school regulations

The first article of the Number 51 supplement is a guide to American school regulations. It consumes half of the entire issue (1a-4a) and bears the following title.

|

華盛頓わしんとんニアル森代理公使ヨリ外務省ニ送おくラレシ米国學校規則要覧べいこくがくこうきそくようらん America school regulation guide sent to the Ministry of Exterior [Foreign] Affairs from [by] Representative-minister [Chargé d'affaires, Ambassador] Mori in Washington |

Articles 1-9 of the regulations immediately follow the title. An indent1ed commentary at the end (4a) states that the articles were published at the request of "His Excellency Mori Arinori" (森有禮閣下) in order that they be "known everywhere in Japan" (日本國中こくちう普知ふち あまねくしられ).

Mori (1847-1889) served as Japan's first ambassador to the United States from 1871-1873. After his return, the year this article was published, he was active as both an educator and diplomat.

Mori became Japan's first Minister of Education in 1885. Successivly appointed in 1888, he died in office the following year at age of 41. He is credited with the national education system that continues, though revised, to define public education in Japan today.

All okurigana in both the regulations and the commentary are written in katakana, unlike the domestic reports that follow, which use hiragana.

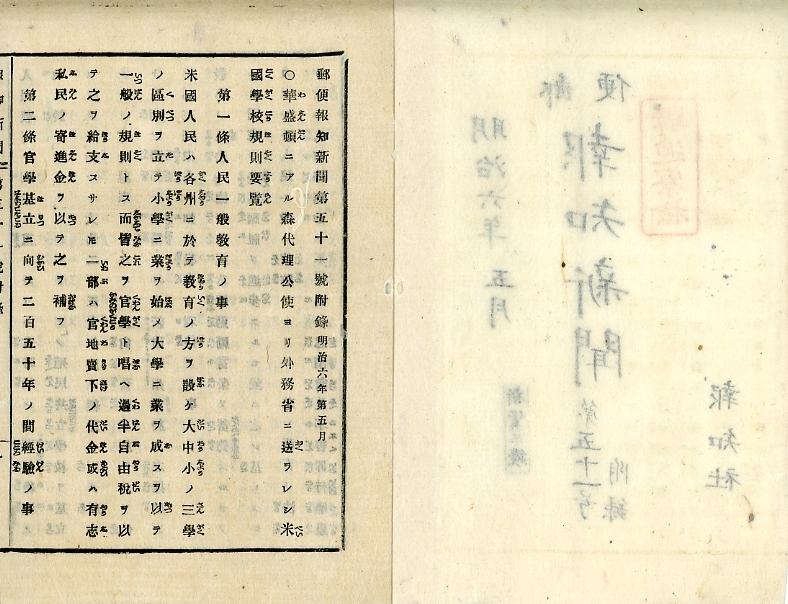

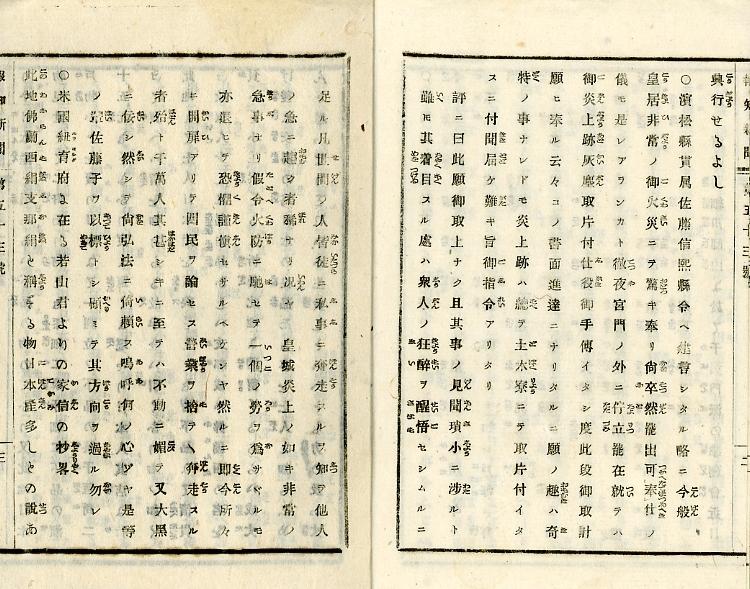

Hochi Number 53

|

The format of Number 53, dated Meiji 6-5 (May 1873), is that of a typical 7-folio pamphlet edition of the paper. The numbered leaves, however, were with metal type.

The copy in Yosha Bunko is of the slighly smaller 14.5 by 21.0 cm size, possibly a facsimile. Publisher's remarks and particulars are woodblock printed inside front and back covers.

"Japan made" goods in New York

Includes numerous reports, most of them concerning other countries, and/or their people in Japan. One long report, exceeding two pages (3a-4b), consists of a digest of a letter (家信かしん てがみ) from a Mr. Wakayama, in New York City (米國紐育ニウヨルク府) in America, to his family. The digest begins with the observation there are rumors that many goods called France-silks and China-silks are Japan-made, whereas only inferior (下品げひん) goods are chanted [billed] as being Japan-made. A couple of Japan-goods shops were selling lacquerware, ivoryware, and inferior ceramics), and selling inferior "cake drawers" (菓子箪笥かしたんす) -- small lacquerware boxes with two or three drawers for putting cakes such as those served with tea -- that would go in Japan for about 1 yen --- for 25 dollars (元どる) -- and reducing the price by half for Japanese shoppers knowing their value.

Tokyo beef lovers beware

The second to last report, on the very last page of this issue, is the following three-line brief directed at people who like beef (page 7b).

|

開拓使かいたくし澁谷しぶや御用地に畜かへる和牛わぎう にほんうし當五月一日より十五日迄に二十九頭ひき斃死たおれしし外にも煩はづらい付たる由全く傳染病でんせんびようと察さつせられたり牛肉ぎうにくを好このむ者用心すへき事なり The Opening-and-cultivation office [Development agency] [reported that] -- [as for] the Yamato steers (Japan cattle) [Wagyū (Nihon ushi)] [it] breeds at the Shibuya state grounds [imperial land] -- from the 1st to the 15th of this 5th month, 29 head fell dead, and moreover the reason they were afflicted is indeed conjectured to be a contanegous disease. Those who like steer-meat [beef] [gyūniku] should be careful. |

Hochi Number 63

Number 63 is printed with metal type on both sides of a broadsheet measuring 48.8 x 34.7 cm which, when folded, made a folio of four 24.4 x 34.7 cm pages. This issue -- dated 12 June 1873, a Thursday -- was published within the first week after Yūbin hōchi shinbun changed its frequency and format from a weekly pamphlet to a daily broadsheet.

The layout of the new format was also significantly different. The content is well organized in clearly labeled departments. The verbose explanation and colophon of the pamphlet edition are gone. The typography of the broadsheet is essentially the same as that of the metal-type pamphlet, but the broadsheet's taller and wider pages, with three bands of text, appear a lot spacier.

Container

Newspapers at the time were contained, as were most publications, between titling in front and publisher disclosers in back.

Front-page banner

Number 63 begins in the upper right corner of the front page with its "banner". Immediately below, in the lower right corner, are the edition's issue number and date particulars, and the day's temperature and tides.

郵便 / 報知新聞

毎日出版

---------------------------

第六十三號

明治六年六月十二日 木曜日

寒暖計 七十八度

潮時満 午前 六 時 十 分

午後六時三十四分

|

Postal / Dispatch news

Published daily

--------------------------------------

Number 63

Meiji 6-6-12 [12 June 1873] Thursday

Temperature 78 degrees

High tides AM 6:10

PM 6:34

|

Back-page colophon

The paper ends in the lower left corner of the back page with the publisher's address and name.

|

兩國米澤町三丁目 |

Ryōgoku Yonezawachō 3-chōme |

Departments

News reports in the pamphlet edition of Yūbin hōchi shinbun were differentiated from each other by a circle at the top of a new line of text. In some cases the first line was short and functioned as a headline. In other cases the first line was simply the lead of the article. The articles were rarely grouped by topic, and there were no topical titles.

The broadsheet format compartmentalized news in a number of clearly titled categories. The titles of the departments in Number 63 are as follows.

Promulgations 公布 (pages 1-2)

Five laws, consisting of four Great Council of State proclamations (Numbers 200-203), and one Tokyo Prefecture ordinance (Kon Number 81).

All five laws were promulgated on the day of the paper's publication. The four GCS proclamations were made over the name of [Prime] Minister of the Great Council of State [Chancellor of the Realm] (太政大臣) Sanjō Sanetomi (三條實美、三条実美 1837-1891).

The single Tokyo ordinance was made over the name of Governor Ōkubo Ichiō (大久保一翁 1818-1888).

Kon (坤) in the numbering of the Tokyo ordinance is a classifier meaning something like "2" or "B". Prefectural directives were numbered "kenkon" (乾坤) categories. The two graphs reflect the "first" (乾 ken: heaven, father, south, etc.) and "second" (坤 kon: earth, mother, north, etc.) in one list (of several lists) of the "eight signs" (八卦 hokke) used in various schools of cosmology and divination.

This usage of the graphs compares with the more familiar use of the "kōotsu" (甲乙) scheme, in which the "ten stems" (十干 jikkan), beginning with "A" (甲 kō) and "B" (乙 otsu), are used to group or classify things, or indicate the relationship between things, such as ministerial orders and circulars, parties to a contract or lawsuit, or the ranking of items on a list or in an outline.

Prefecture dispatches 諸縣報知 (page 2)

Two articles concerning prefectural (i.e., domestic) matters.

The first article is a dispatch from Mino-no-kuni Motosu-gun Mieji-eki, in Aichi [(sic) Gifu?] prefecture, about a man who had "entered the gates of Nenbutsu" [became a practioner of the Jodō sect of Buddhism], in repentance of having once been so unfilial that he had given his father poison.

The second article reports the apointment of a German to a hospital in Nagoya and other particulars about the hospital (see full translation and commentary below).

Trials 公判 [(Criminal) court hearings] (page 2)

Report of a court decision in a Tokyo prefecture 4-daiku 9-shōku case concerning a 24-year-old man affiliated with Kohinata Suidōchō (part of Kohinata in present-day Bunkyō-ku). The man was sentenced to three years of penal servitude with heavy labor for swindling a watchmaker out of gold-and-silver pocket watches and chains, which he later sold to a certain Frenchman in Yokohama and pawned, for 297 yen.

Foreign news 外國新報 [Outside-country new-reports (bulletins)] (pages 2-3)

Two reports about matters in other countries.

The first foreign news report is a 15 May dispatch from Vienna (Wiener, Wien) the capital of Austria (墺地利アーストリエノ京都ウインナ Aasutorie no miyako Uinna), concerning a ravaging storm.

The second report is a 16 May dispatch from London (倫敦) to the effect that the Emperor of Persia (波兒斯ペルシエ皇帝) was about to arrive in Wiener (維也納ウインナ) with his ministers and three empresses (后きさき)on a trip to Europe (歐羅巴) that would be costing 25,000,000 yen.

The first kana in the furigana for Austria in the first report is not clear. I have read it アー but it could be オー or even ヤー. The kana orthography for "Österreich" become came to be standardized as オーストリア (Oostoriya).

Note that whereas "Vienna" is represented in katakana in the first report, in the second it is shown in kanji with furigana.

The second report is followed by a critical comment attributed to its translator (see full translation and commentary below).

The most striking typographical feature of the two reports in the foreign news department is that their okurigana are written in katakana -- whereas all reports in other departments use hiragana. Katakana otherwise appear in other articles only as transliterations -- e.g., インハンス (Inhansu [sic] Junghans) in the second prefectural report (see translation below), and コレラ (korera < colera) in the second submitted opinion (see next).

Contributions 投書 [Submitted writing] (pages 3-4)

Two articles apparently sent to the paper.

These are the last stories in the paper. Neither in attributed, but both appear to be what today would be called an op-ed or letter to the editor.

The second -- nearly a page in length, the longest in the paper, nearly twice as long as the Tokyo court decision -- concerns the threat to health of filth in public places.

Commodity prices 物品時價 [Things-goods current-prices] (page 4)

This, the last department, reports the day's prices of "rice" (米 kome) and "water oil" (水油 mizuabura), meaning rape-seed oil and other such vegetable oils used to make lamp oil.

German man hired by Nagoya hospital

The second prefectural dispatch concerns the employment of a German man by a Nagoya hospital and other particulars about the facility (page 2).

|

名古屋表に在ある本願寺西掛所かけしよは今度假かり病院となりて獨逸どいつ人インハンスなる者を雇やとひ近日開院かいいんある由右病院一ヶ月の費用は千圓にて院長いんちやうの給は一月四百圓なりと The West Support-place [West Branch] [of] Honganji in Nagoya has now become a temporary hospital [medical institution] and employed the German Inhansu. For soon it will open a hospital. The expenses of [for] one month [for] the right [mentioned] hospital are 1,000 yen and the salary of the hospital [insitution] head is 400 yen a month. |

the German Inhansu (Doitsujin Inhansu naru mono) appears to be the "Dr. Junghans" mentioned in the memoirs of the British civil engineer Edmund Gerald Holtham, hired by the government of Japan to help develop the country's railway system.

E. G. Holtham

Eight Years in Japan, 1873-1881

, Work, Travel, and Recreation

London: Kegan Paul, Trench & Company, 1883

vii, 361 pages, maps, publisher ads, hardcover

Holtham, referring to a third party, states that "with the advice of a kind German doctor attached to the general hospital at Nagōya [sic], one Dr. Junghans, the patient worked successfully through his attack" (page 98). Holtham, who traveled and worked all over Japan, was in Nagaoya a number of times.

German or American?

Both Holtham, and the writers of the Hochi article, describe Junghans as a "German" -- while 1876 publication of his lectures association him with "America". It appears Junghans was in fact an American, though of German descent, and apparently, after his contract ended in 1876, he returned to the United States and opened a medical practice near New York.

Nagoya University Hospital

Nagoya University Hospital traces its history back to 1871, when a temporary medical facility was built in Nagoya. The facility was closed in February 1873 and a replacement planned. In May, the planners hired the American physician Junghans (ヨングハンス T.W. Yunghans? T.H. Yunghaus?] and the Kagoshima shizoku Adachi Moriyoshi (足立盛至) as instructors.

A temporary medical facility established in 1871 was closed in Febrary 1873 and provisions were made for building a new facility. In May, the head of the project hired the American phyisician Junghans and the Kagoshima shizoku Adachi Moriyoshi as instructors, and a temporary hospital was built at Nishi Honganji.

In October 1873, Junghans conducted the first autopsy at the provisional facility on the cadaver of someone who had been executed. The following month, a classroom was set up and Junghans gave his first lecture in English. In September he transplanted skin to a burn patient.

The two volumes of Junghan's lectures were published in February and April. In April, when their terms of employment expired, he and Adachi were relieved of their duties.

Essentials of Primigenum

The National Diet Library "Recent era digital library" has scans of the entire contents of the following work.

米国雍翰斯氏講義 / 原生要論

名古屋:愛知師範学校

巻之一:明治九年二月五日

巻之二:明治九年四月廿四日Beikoku Yongu-han-su shi kōgi / Gensei yōron

[Lectures of Mr. Junghans of America / Essentials of Primigenum]

Nagoya: Aichi Shihan Gakkō [Aichi Normal School]

Volume 1: 5 February 1876

Volume 2: 24 April 1876

The colophons of both volumes state that the lectures were interpreted by Suzuki Muneyasu (鈴木宗泰), transcribed by Ishii Eizō (石井栄三), and edited by Hachisuga Kenkichi (蜂須賀謙吉).

Ishii wrote the preface in kanbun and the explanation (例言) in Japanese. The explanation, dated November 1875, gives Junghan's name as 雍翰斯ヨンハンス or "Yon-han-su" -- which would be pronounced "Yoŋ-han-su" hence "Yonghans" -- apparently for "Junghans".

The provided reading of 雍翰斯 is clearly Chinese. The graphs would be transliterated "Yong-han-ssu" in the contemporary Wade system (later Wade-Giles), or "Yōnghànsī" in today's Pinyin -- whereas the Hepburn romanization of a Sino-Japanese reading would be "Yō-kan-shi" or "Yu-kan-shi".

Significantly, the title slip of the covers of both volumes read 雍氏講義 / 原生要論 -- i.e., the first graph of "Yonghansu" is taken to represent the entire name. This, too, is a Chinese convention adopted in Japanese. I have not been able to learn anything else about Junghans, but it is possible that he was employed in Japan after having been in China, possibly Shanghai, andacquired the sinific name there.

The very first line of the introductory lecture (from page 11) defines 原生学 (genseigaku) as follows (page 11).

|

夫レ原生學ハ有機體 動植 / 二物 ノ常態變化ヲ論ズル所ノ者ナリ Now, as for basic-life-studies [physiology], it is one of where [a study in which] [we] discuss the normal changes of [in] organic bodies (both animals and plants). |

Subsequent lectures presented the basics of what today would be called "seirigaku" (生理学) or "physiology". The term "genbyōgaku" (原病学) was used to mean what is now "byōrigaku" (病理学) or "pathology".

Painful misfortunes of Asia's people

The indent1ed comment attributed to the translator, following the article reporting the costs of the Shah of Persia's European travels, reads as follows (page 3).

|

譯史氏云一國博覧會ヲ開クニ當リ其他ノ國ヨリ民ノ貢金ヲ用テ官遊スル者歐羅巴ニ有リヤ否ヤ維也納帝家ノ墺國博覧會ニ費ス金ハ其國民ノ膏血ナリ亜細亜人民ノ不幸豈ニ痛マシカラズヤ The translator says: No sooner than, when one [European] country [nation] opens an exposition, people who officially travel [there] from other countries [nations] using the contributed money of the affiliates [of their country], are in Europe, and the money the Persia Imperial Family is expending on the Austria Exposition is the fat-and-blood of their country-affiliates [nationals]. The misfortunes of Asia's people are so painful! |

The World Fair -- the fifth of its kind and the first not in England or France -- was held in Vienna from 1 May to 2 November 1873.

The "Emperor of Persia" was Nasser al-Din Shah Qajar (1831-1896), the King and Shah of Persia from 1848 until his assassination in 1896. He is known today mainly through his diaries, which were published in Persia's official gazette.

The diaries of his travels through Europe, on the occasion of the 1873 World Fair in Vienna, were quickly published in English by a British Orientalist who had mastered Turkish, and Persian and Arabic, while working in the Ottoman service.

H.M. Shah of Persia

The Diary of H.M. The Shah of Persia,

during his Tour through Europe in A.D. 1873.

By J.W. Redhouse.

A verbatim translation.

With Portrait.

Third Thousand.

London: John Murray, Albemarle Street, 1874.

xx, 427, frontispiece portrait, hardcover

Sir James William Redhouse (1811-1892), after about two decades in the employ of the Ottomans as a translator, apparently in mostly naval and diplomatic assignments, returned to England, where he became a scholar of the Orient and an authority on Turkish and Ottoman Turkish but also Persian and Arabic. As such he continued to promote amicable relations between Europe and the Orient, hence his translation of the Shah's diary.

In his translator's preface, Redhouse remarks that, in publishing narratives of his excursions "beyond his own dominions . . . for the imformation of his people, [the Shah was] therein following a praiseworthy example set by several ancient Rulers of his own original Turk nationality" (page v). The diaries were shared with the Persian public by publication in the Teherān Gazette, and as such Redhouse compares them reports in the "Court Circular" in Britain.

Redhouse concludes his preface with the following remark on his objectives as a translator (page viii, underscoring mine).

|

The translator wishes, and ventures to hope, that his effort to put the whole work into an English dress may give to its readers the same amount of pleasure he has himself felt in the performance. May he be further permitted to express a heartfelt trust that ever-strengthening ties of friendly and beneficial intercourse may be facilitated and multiplied, through the effects of this tour, between the Court and people of Persia on the one hand, and the Western Rulers and nations on the other, some of them their not remotely allied cousins by race, as indicated by affinities of language, [Note *] and who are no longer personally strangers to their travelled Sovereign. London, Nov. 1874. [Note *] [The footnote, omitted here, consists of a brief list of words that Persian shares in common with English -- to illustrate why "Persian" and "Western" peoples were "not remotely allied cousins by race, as indicated by affinities of language". The translator's preface is followed by a long guide to the pronunciation of Persian names and other linguistics matters. ] |

I suspect -- without having searched for evidence to support or refute my suspicion -- that the good Shah commissioned Redhouse to do the translation.

Sources and commentary

The following articles and books are among others consulted in the above pursuit of some of the stories in the early issues of Yōbin hōchi shinbun. Only sources not reviewed in the Bibliography on this website, or already described above, are listed here.

Newspaper history

Iwata 2009

The following article by Iwata Takaaki can be downloaded from the website of Yasuda Women's University / Yasuda Women's College Library.

岩田高明

官板海外新聞の西洋教育・学術情報

(『官板六合叢談』を中心に)

安田女子大学紀要

第37号、2009

ページ129-138Iwata Takaaki < Takaaki IWATA >

Kanpan gaigai shinbun no seiyō kyōiku・gakujutsu jōhō

("Kanpan Rikugō sōdan" o chūshin ni)

[ Information on western-ocean education and technology in officially published overseas news

(Centering on "Kanpan Rikigō sōdan") ]

< A Study of European Education and Science Information in Foreign Newspapers Published by the Edo Shogunate: An Analysis of KANPAN-RIKUGOSODAN >

Yasuda Joshi Daigaku kiyō

[Bulletin of Yasuda Women's University]

Volume 37, 2009

Pages 129-138

Kawabe 1921

I do not have a copy of the following publication but various formats of several original copies can be downloaded from The Internet Archieve.

Kisaburō Kawabé

The Press and Politics in Japan

(A Study of the Relation Between the Newspaper and the Political Development of Modern Japan)

The University of Chicago Press, February 1921

xiii, 190 pages

For more about Kawabe, see his comments below on Yorozuya Heishiro, Rikugo sodan, and Hochi shinbun.

Masuda 2000

Parts of the following publication can be read on Google Books. The author, Masuda Wataru (1903-1977), was a professor of Osaka Municipal University and Kansai University. The translator, Joshua Fogel, then a professor of history at the University of California at Santa Barbara, is now at York University in Toronto.

Masuda Wataru

ix, 298 pages

Translated by Joshua A. Fogel

Japan and China: Mutual Representations in the Modern Era New York: St. Martin's Press, 2000

This is a translation of the following posthumous collection of the series of articles Masuda had been writing for a monthly publication at the time of his death, plus a few other articles. Masuda, an ardent bibliophile and collector of Chinese and Japanese publications from the middle of the 19th century to the time of his own life, frequently refers to, and cites from, the materials in his own collection.

増田渉

西学東漸と中国事情:「雑書」札記

東京:岩波書店、1979

370ページMasuda Wataru

Seigaku tōzen to Chūgoku jijō: "Zakki" reki [The eastern progress of western learning and circumstances in China: Notes on "Miscellaneous publications"]

Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1979

370 pages

Nagasaki

Blusse 2008

No book on the subject of commerce in East and Southeast Asia is quite as fascinating as this compact volume -- on Canton, Nagasaki, and Batavia at the end of the 18th and start of the 19th centuries -- by the world's foremost expert on the Dutch East India Company and related topics -- who, fortunately, is also a brilliant writer.

Leonard Blusse

Visible Cities

(Canton, Nagasaki, and Batavia and the Coming of the Americans)

[Edwin O Reischauer Lectures]

Cambridge (MT): Harvard University Press, 2008

xi, 133 pages, hardcover, jacket

Lee and Nagai 1996 and 1997

The authors of the following two articles were both, at the time, affiliated with the Department of Architecture, Faculty of Engineering, Kansai University (関西大学工学部建築学科), Lee as a graduate student, Nagai as a professor. Both articles are available as PDF files from the NII Electronic Library Service of the National Institute of Informatics (NII), Scholarly and Academic Information Nagivator.

Both articles, in Japanese, begin with very brief abstracts in English which are not very comprehensible. The articles include a number of illustrations from older maps and drawings, including pictoral representations, and some ground diagrams. The studies are more than "architectural" in that they suggest the manner of life at once facilitated and limited by the manner in which the Chinese quarters were built and managed.

The English in <angle brackets> is as received. The English in [square brackets] is mine.

李陽浩、永井規男

元祿年間における長崎唐人屋敷の構成について

(長崎唐人屋敷に関する建築的研究 その1)

日本建築学会計画系論文集

第482号、1996年4月、ページ175-184

李陽浩、永井規男

天明年間から文化年間における長崎唐人屋敷の構成について

(長崎唐人屋敷に関する建築的研究 その2)

日本建築学会計画系論文集

第499号、1997年9月、ページ163-170< Yangho LEE, Norio NAGAI >

< ON THE COMPOSITION OF CHINESE SETTLEMENT OF NAGASAKI IN GENROKU PERIOD -- A [architectural] study of chinese settlement of Nagasaki Part 1 -- >

< ON THE COMPOSITION OF CHINESE SETTLEMENT OF NAGASAKI FROM TENMEI TO BUNKA PERIOD -- A [architectural] study of chinese settlement of Nagasaki Part 2 -- >

< J. Archit. Plann. Environ. Eng., AIJ >

[ Journal of Architectural Planning and Environmental Engineering, Architectural Institute of Japan ]

Part 1: < No. 482, 175-184, Apr., 1996 >

Part 2: < No. 499, 163-170, Sep., 1997 >

Takeno 1977

This is one of the most useful popular collections of maps and other graphic images, and photographs of sites, related mainly to Nagasaki during the Tokugawa period.

武野要子 (編)

長崎・平戸

(日本の古地図14)

東京:講談社、昭和52年7月25日 (第1版)

36ページ、大判 (26.5x36 cm)

Takeno Yōko

Nagasaki, Hirado

(Nihon no kochizu 14)

[Old maps of Japan 14]

Tokyo: Kōdansha, 25 July 1977 (1st printing)

36 pages, ōban (26.5x36 cm)

Facsimiles of Nagasaki maps

The following full-size facsimile of an 1802 map clearly shows the Tōjin Yashiki enclosure on the coast of the mainland and the Shinchi island connected to it and the mainland, as well as Deshima.

肥前長嵜圖 [Hizen Nagasaki zu]

享和二壬戌年 [circa February 1802 to January 1803]

復刻古地図 3-37

東京:人文社、NLT 2010

53.6x75cm

Junwa 2 Jinjutsu nen [circa 1802]

Fukkoku kochizu 3-37 [Reproduction old maps 3-37]

Tokyo: Jinbunsha, NLT 2010

Single sheet in folder

The following full-size facsimile of a 1870 map show the foreign settlement as it developed from 1859, the Chinese settlement as it developed after 1868, and Deshima. A barely readable photographic image of an original copy of this map is shown in Takeno 1977 (pages 16-17).

長嵜港全圖

明治三年庚午八月

復刻古地図 9-27

東京:人文社、NLT 2010

68x102.5cm

Meiji 3-nen Kōgo 8-gatsu [circa September 1870]

Fukkoku kochizu 9-27 [Reproduction old maps 9-27]

Tokyo: Jinbunsha, NLT 2010

Single sheet in folder

Kawabe on Yorozuya Heishiro, Rikugo sodan, and Hochi shinbun

Kawabe Kisaburō (川辺喜三郎 1885-1964) graduated from the law department of Waseda University in 1907 and went to the United States, where he studied at Stanford, Berkeley, and Wisconsin before receiving a doctorate at the University of Chicago. He returned to Japan in 1921 and from 1922 he taught at Waseda and Komazawa.

Kawabe's The Press and Politics in Japan, subtitled "A Study of the Relation Between the Newspaper and the Political Development of Modern Japan" (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1921), was apparently based on his doctoral disseration in sociology.

The first graph of the one-page Preface -- dated Chicago, Illinoi 1920 -- is interesting as an account of how Kawabe, isolated in the United States, was able to obtain some of the details he reported in the book (page vii).

|

PREFACE My purpose in this work is to show the influence of the press upon the political life of Japan. For such success as I have attained in overcoming the great difficulties caused by the complexity of the problem and the lack of access (owing to my residence in America) to the original Japanese sources, I am chiefly indebted to my younger brother Sukejūrō Kawabé, who, for four years, has constantly labored in Japan to supply me with the necessary information and materials. It was through his untiring co-operation that I was enabled to complete this book. [ Rest omitted. ] |

Here is what Kawabe wrote about Yorozuro Heishiro, Rikugo sodan, and Yubin hochi shinbun (pages 38-39, note on 40, and bibliography).

CHAPTER VI [ Introduction omitted ] The modern Japanese newspaper originated in the translation of Western newspapers by the government. In 1811 the Tokugawa Shogunate made it a part of the work of the Astronomical Observatory to translate Western literature. Under the regime of Shogun Yoshimune (1713-44) Dutch literature had been introduced, and until 1860 it was the only Western literature studied by the Japanese. But in 1860 English, French, German, and Russian were also taken up by the Department of Translation, which name was then changed to the "Bureau for the Investigation of Western Literatures' 7 (Yosho Shirabedokoro). This bureau was the origin of the Kaisei College, the present Imperial University of Tokyo. [Note 1] Yorozuya Heishiro, the director of the bureau, in 1864 published the translation of a Dutch newspaper of Batavia, Java, as the Batavia News (Kamban Batavia Shimbun). This paper was printed by means of movable wood types, invented at the beginning of the seventeenth century, and was sold to the public through the Rohokan [sic] bookstore by the government's order. The contents were a sort of foreign news, which, being quite out of date, could not constitute a newspaper in a strict sense. [Note 1, page 38] In 1868 the new government changed the name of the Kaisei College to the Daigaku Nanko, and in 1877 it was combined with the Tokyo Medical College and was named the Tokyo University. Then it had four departments law, medicine, science, and literature. In 1886 its name was again changed to the Tokyo Imperial University, and subsequently many more departments were added. In the same year the Foreign News (Kaigai Shimbun), a translation of New York war news, and three other papers of similar nature made their appearance. They were the Universal News (Rikugo Sodan), Hongkong Shimbun, and Foreign News (Kaigai Shimpo), all of which were sold through the Rohokan [sic] bookstore. They were broadsides, printed on several sheets of hanshi, [Note 1] and containing no editorial, no political or other contemporary news of Japan, and no advertising. The readers were limited to a small number of educated samurai, and the circulation was insignificant, perhaps several hundred for each issue. [Note 1, page 40] Japanese paper 9½ X 12 inches. In March, 1868, under the new regime, the Dajokan Nisshi (Diary of the Privy Council) was published in Kyoto, and in May of the same year Kojo Nisshi (Diary of Yedo Castle) was published. As they were government enterprises, a large number of copies were printed and distributed regardless of expense. The subscribers were principally the officers of the central and local governments and school teachers. These two papers were the origin of the new government's official gazette which has further developed. Having been stimulated by the central government's example, organs were published by prefectural authorities, numbers of private newspapers appeared, and by the end of 1868 there were ten official gazettes and fifteen private papers. They had few editorials, and the greater part of the paper was filled with general news of the civil war which was going on at that time. The following article by Mr. Ishikawa illustrates the situation of those days: The Hochi Shimbun was the first government organ published through the suggestion, of Mitsu Mayejima, the Minister of Communication, and was called the Yubin Hochi Shimbun (Mail Reporting News). At that time this paper was proud of being a government organ. [ Rest of article omitted ] [ Citation note, page 40 ] Hanzan Ishikawa, special article in Shimbun Kogiroku, pp. 5-6.

AMATEUR JOURNALISM

[ Bibliography shows undated book, "Dai-Nippon Shimbun Gakkai. Shimbun Kogiroku (Transcripts of Lectures on Journalism)." ]

[ Bibliography also shows two articles by Ishikawa Hanzan on the development of newspapers, dated 1915 and 1919. ]

[ The 1910s marked half a century since the last years of Tokugawa period and the start of the Meiji era. Kawabé's book, published in 1921, reflects in English the wave of writing in Japanese on the recent history of journalism in Japan. ]

Kanpan Rikugo sodan publisher Yorozuya Heishiro

The inside of the back back cover of Volume 4 in Waseda University Library hows the following information about the publisher (my romanization).

Yorodzuya Heishirō (1818-1894) is supposed to have the director of the Bureau for the Inspection of Barbarian Books |