Taiwan

The legal integration of Formosa

By William Wetherall

First posted 1 January 2007

Last updated 1 November 2023

Sino-Japanese War

Origins in Korea

•

Hop to Liaotung

•

Skip to Shantung

•

Jump to Penghu

•

Truce and treaty

Taiwan

Taiwan-Japanese War

•

Government-General of Taiwan

•

Family registers

•

Civil Code

•

Nationality

•

Mixed alliances

•

Penal Code

Taiwan publications

General statistics

•

Vital statistics

•

Police statistics

•

"Race boxes"

•

Aboriginal classifications

1911 marriage statistics

Terminology

•

Clans of spouses

•

Types of spouses

•

Status of spouses

Takekoshi 1905

Goto's preface

•

Takekoshi's foreword

•

Sham republic

•

Race

•

Convicts and defendants

•

Raw savages

Nitobe Inazō and Taiwan

Marriage

•

Shokusan Kyoku

•

Tug of war

•

Bushido

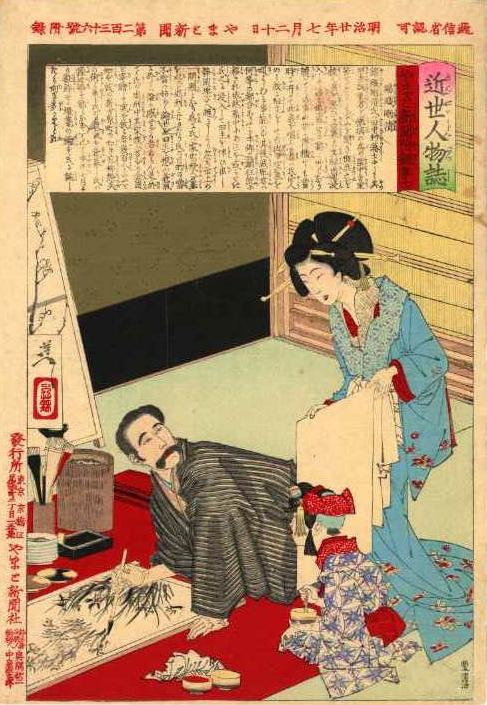

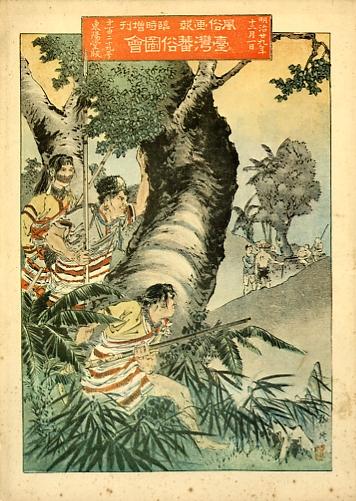

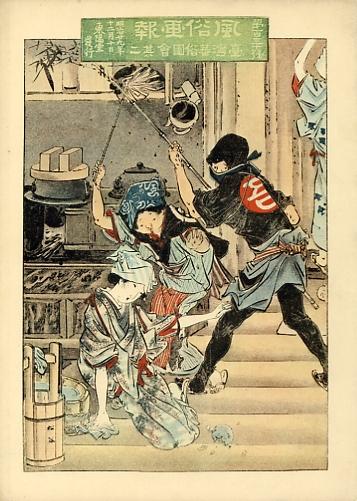

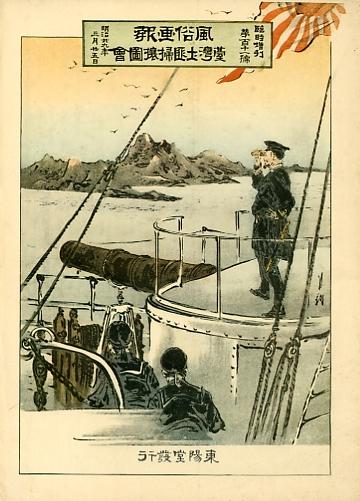

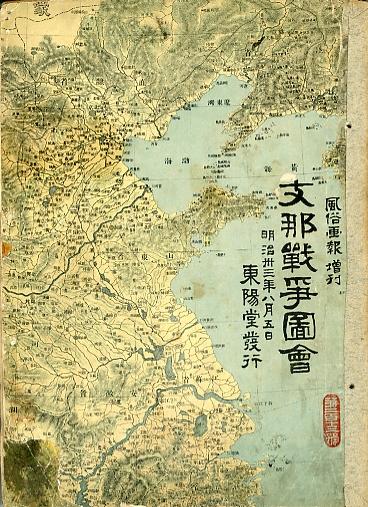

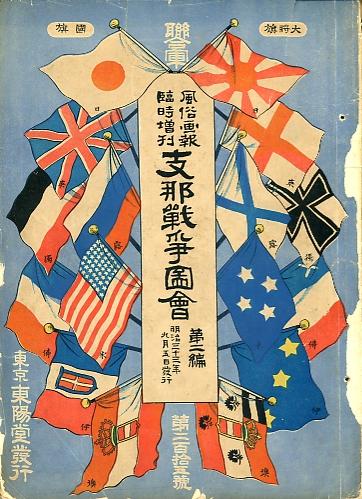

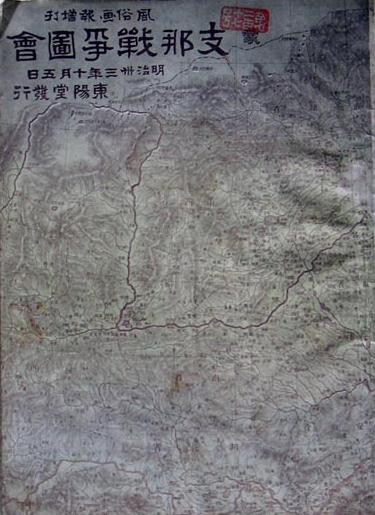

Fuzoku gaho

Taiwan savage customs 1895

•

China war 1900

Related article

Taiwan reports: Ilha Formosa -- "Island Beautiful" -- invites you

Sino-Japanese War

The Sino-Japanese War is one of the most controversial events in history of East Asia at the tend of the 19th century. Publicized "information" about the war leans strongly toward the view that China and Korea were victims of Japanese aggression and imperialism.

These are easy charges to make in a climate of political (and policized scholarly) opinion that has little tolerance for the notion that any other state in Japan's position would also have considered China's military initiative in Korea in 1894 a violation of the treaty that China and Japan had signed in 1885 regarding the independence of Korea.

China and Japan, having agreed in the 1885 Treaty of Tientsin to withdraw their military forces in Korea, and encourage Korea to develop its own defense forces, would naturally attempt to gain favorable treatment from Korea as Korea developed an independent government. Neither China nor Japan would benefit from a hostile Korean government, but given the hostility between the two countries, both had reason to fear the dominance of the other over Korea.

From its point of view, China perceived attempts by some Koreans to overthrow the still fairly pro-China Korean government as to its disadvantage. It also had reason to believe that, while many of the rebels were also anti-Japanese, some of the civil disturbances were being instigated by Japan.

From its point of view, Japan would want to permit -- encourage and even instigate -- the establishment of a Korean government that would turn to Japan as a model of legal reform and industrialization as to its advantage. Hence it was to Japan's interest to allow the rebellion to take its natural course, and not interfere unless the rebels threatened its legation or other properties.

Inevitably, though, neither China nor Japan were of a mind to permit the other state to unilaterlly dispatch armed forces to Korea, on any pretext. Japan obviously had difficulty with the fact that the Korean government had asked China, and not Japan, for military support against the rebels.

Seen in this light, the Korean government sparked the Sino-Japanese War, first by failing to defend itself, and then by inviting only China to come to its aid. Given the diplomatic imperatives of the times, which emphasized military responses, Japan could not possibly have stood by and allowed China to rescue the failing Korean government on its own terms.

The swiftness with which Japan responded to the situation on the peninsula was a showcase of "crisis management". Japan quickly marshalled enormous military and other resources to impose an essentially pro-Japanese order on the Korean government, destroy much of China's fleet in the Yellow Sea, and drive Chinese forces out of Korea.

Recent East Asian history would have been totally different if Japan had stopped at the Yalu river. Japan's military strategists, however, found themselves on a roll. Taken advantage of the momentum of Japan's advance and China's retreat, they crossed the Yalu and took the Tengtien (Liaotung) peninsula. They also crossed the mouth of the Pohai sea and took Weihaiwei, thus gaining naval supremacy at the Yellow Sea gateway to Peking.

Japan's next move was as brilliant as it was conniving and even deceptive. After peace negotations had already started, Japan -- coveting Taiwan as a territorial prize -- invaded and occupied the Penghu islands, thus preventing China from reinforcing Taiwan, and positioning itself to invade Taiwan and ports along China's continental coast should the war drag on.

Japan's actions on Korea are understandable -- rational, even just -- given the nature of its relationship with both China and Korea, and contemporary standards of diplomacy. However, Japan's actions beyond the Yalu and the Yellow Sea are unstandable only as those of a state that had become territorially greedy and politically arrogant.

Japan's greed and arrogance are clearly seen in the terms of the Treaty of Shimonoseki -- which ended the Sino-Japanese War but started the Taiwan-Japanese War, and set the stage for the Russo-Japanese War. Every later imperialistic step Japan took on the Asian continent in the 1920s and 1930s, and in Southeast Asia and the Pacific in the 1940s, can be traced to Japan's fateful decision to cross the Yalu river and Yellow Sea during the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895.

Origins in Korea

Japan's involvement in affairs on the Korean peninsula go back to the start of Japanese history, meaning the earliest written accounts of events in what are today Japan, the Republic of Korea, and the Democratic People's Republic of Korea. There were periods when contacts between entities in the Japanese islands and the Korean peninsula were infrequent, but generally speaking, there have always been exchanges of one kind or another between entities on the islands and the peninsula.

The so-called centuries of relative seclusion during the Tokugawa period witnessed a fairly constant trade between Japan and Korea with occasionally exchanges of missions and, at times, the presence of a Japanese legation in Korea. Ties between the two entities intensified during the Meiji era, largely in the forms of frictions created by Korea's inability or failure to adequantly defend itself from the predatory interests of its nearest neighbors and several Euroamerican countries.

Korea, which had become essentially a tributory of China, was also coveted by Russia. The peninsula was problematic for Japan to the extent that it would be unfriendly toward Japan as a result of its alliances with other countries. Conquest or control of Korea by a country that was hostile to Japan could impede its industrialization and otherwise threaten its geographical security.

While any number of sparks could have ignited the Sino-Japanese War, the war was mostly triggered by an acute outbreak of tensions that had been festering between China and Japan since the late 1860s. These tensions involved all manner of issues, including China's control of Okinawa and its lack of control of Taiwan.

Korea had been the object of Sino-Japanese disputes during the 1870s and 1880s. By the 1890s, Japan's desire that Korea become an independent state friendly toward Japan had inspired more Koreans to endeavor to end China's control of Korean affairs.

Civil disturbances in Korea -- including clashes between pro-Chinese and anti-Chinese Korean factions, some of the latter pro-Japanese -- provoked China to send troops to Korea. China gave Japan prior notice, as required by the 1885 Treaty of Tientsin (Tianjin).

However, the treaty presumed the necessity of a troop dispatch, and Japan did not recognize a need for Chinese troops in Korea. Viewing China's actions as a violation of the treaty, Japan its own troops, and inevitably the two forces collided.

The Treaty of Tientsin had followed by only three years the 1882 Treay of Chemulpo, which marked the legal start of Japan's military presence on the peninsula in the late 19th century.

1882 Treaty of Chemulpo

The Treaty of Chemulpo begins the recognition that, on the 9th day of the 6th month on Chosen's calendar, and the 23rd day of 7th month on Japan's calendar, in reign years corresponding to 1882, the Japanese legation in Hansong (���� J. Kanjō, WG Hancheng, PY Hanzheng) was overrun by mobs of Chosen heinous villains (���N���k). Some Japanese officials and staff were killed. Others fled to Chemulpo and from there to Nagasaki. Hansong and Chemulpo (�ϕ��Y Chemulp'o) are now known as Seoul and Inchon.

Japan sent warships and troops to protect its people and property. China sent its own troops to protect its interests, which included preventing Japan from doing more than reclaiming its legation.

On 30 August 1882, Chosen (���N��) and Japan (���{��) signed the Treaty of Chemulpo (�ϕ��Y���) [�Z���Y����], which is written in Chinese. In the treaty, Korea agreed to, among other things, pay indemnities to the families of the victims, compensate Japan for damages to the legation and costs of dispatching land and marine forces to protect it, and permit Japan to garrison troops and some police in the legation for its protection (Japan would withdraw the troops in one year if security improved).

1885 Treaty of Tientsin

The Treaty of Tientsin (PY Tianjin) resolved a collision between Chinese and Japanese forces that had taken place the year before. The treaty provided that both countries would withdraw their military forces from Chosen, and that neither country would dispatch troops to the peninsula except when necessary and only with prior notification to the other country. In the meantime, Chosen would be encouraged to develop its own military forces with the help of other states if that was Korea's wish.

Signed on 18 April 1885, the Treaty of Tientsin had both Chinese and Japanese versions. Both versions refer to the entity of contention between the two states as ���N (J Chōsen) or "Chosen" and to the sovereign of the entity as ���N���� (J Chōsen kokuō) or "king of country of Chosen".

Sources

The above treaty particulars were viewed on scans of original copies of the 1882 Treaty of Chemulpo and the 1885 Treaty of Tientsin on the website of �A�W�A���j�����Z���^�[, the Japan Center for Asian Historical Records (JACAR), which is part of ������������, the National Archives of Japan.

Hop to Liaotung

Here are some dates of events that prefigured the start of the Sino-Japanese War.

6 June 1894 China, in accordance with the terms of the 1885 Treaty of Tientsin, notified Japan of its intentions to send military forces to Chosen. The pretext of China's action was that it was responding to requests from the Korean government to help it stop a rebellion that had started a few days earlier.

7 June 1894 Japan, also in accordance with the terms of the 1885 Treaty of Tientsin, notified China of its intentions to send military forces to Chosen. The terms of the treaty presumed the need to dispatch troops, and Japan did not accept the pretext that a third party should intervene in a domestic power struggle.

8 June 1894 Japan lands superior numbers of troops at Chemulpo (now Inchon) and within three days the rebellion are supressed -- with thousands of Japanese troops now in Hansong (now Seoul).

China and Japan negotiate the withdrawal of their military forces, but condition their withdrawal on reform of the Korean government. Each state argues for reforms that would favor its own national interests on the peninsula at the expense of the other state's interests.

Meanwhile, both sides build their naval forces in the Yellow Sea.

By 23 July 1894, Japan has occupied parts of Hansong and the palace, installed a pro-Japanese government, and secured from it a mandate to expel Chinese forces.

25 July 1894 Battle of Pungdo Offing (�L�����C��). In this first naval controntation of the war, Japan prevents China from landing ground forces at Asan to reinforce its forces there and at nearby Sŏnghwan, from which they could march on Hansong (Seoul).

Pungdo (�L��) is an island at the mouth of Asan bay, which opens on the Yellow Sea. Pungdo offing (�L����) is in the Yellow Sea just west of the pay. Asan (��R) and nearby Sŏnghwan (����), like Chemulpo (Inchon) to the north, offered fairly easy overland access to Hansong.

28-30 July 1894 Battle of Sŏnghwan (�������), aka Battle of Asan (��R���). Japanese ground forces defeat Chinese forces at Sŏnghwanin and also occupy Asan. Surviving Chinese forces retreat north to join other Chinese forces at Pyongyong.

1 August 1894 Japan formally declares war on China. An imperial decree (�ُ� shōsho) issued the same day alleges that China (1) had ignored the status of Chosen as standing among the ranks of independent countries, and the treaty which had determined this, (2) had harmed Japan's rights and interests, and (3) did not assure the peace of Asia (���m).

15-16 September 1894 Battle of Pyongyong (������). Japanese troops surround and route Chinese forces at Pyongyong and occupy the city. Surviving Chinese forces retreat north to the Yalu River, which marked the northern boundary between Chosen and Manchuria.

17 September 1894 Battle of Yellow Sea (���C�C��), aka Battle of Yalu River (���]�C��). This was the second and largest naval battle of the war, fought in the Yellow Sea at the mouth of the Yalu River. Surviving Chinese forces cross the Yalu river into Fengtian province province of China.

Fengtien (��V PY Fengtian) province is now Liaoning (�ɔJ) province.

Invasion of China

Presumably Japan's aim in going to war with China was to push Chinese forces out of Korea. That goal was essentially achieved when Japan defeated Chinese forces at Pyongyong.

Given the momentum of the war, and the additional push of territorial ambition, Japan decided to pursue Chinese forces into China -- or what China considered part of China, though Japan had its own view on the status of Manchuria.

24-25 October 1894 Battle of Yalu River (���]���). This small battle took place at the Yalu (WG Yalu-chiang, K Amnok-kang) itself, and nearby areas. Japanese land forces bridged the river from the Korea side to attack and take several China's positions in the area.

This resulted in Japan's occupation of Antung (���� PY Andong), now Dandong (�O�� WG Tantung). From this point, Japan pushed across Fengtien province to Anshan (�ƎR), then swept south down the Liaotung (�ɓ� Liaodong) peninsula to Port Arthur.

By 7 November 1894 Japan had occupied the port town of Talien (��A J Dairen, PY Dalian) just to the north of the port of Lushunk'ou (������ J Ryojunko, PY Lushunkou). Talien, a larger and more protected harbor, was mostly a commercial port. Lushun, a more exposed but strategically better located harbor on the southern tip of Liaotung, was a naval facility.

Lushunk'ou was better known in English as "Port Arthur" -- so-called after a British naval officer who took refuge in the harbor during the Second Opium War.

12 November 1894 The United States proposes conciliation (peace).

21 November 1894 Japanese forces occupy Lushunk'ou (������ Ryojunko, Lushunkou) after pushing into Manchuria and down the Liaotung peninsula overland.

Lushun was situated on the southern tip of the Liaotung (Liaodong) peninsula, which juts into the Yellow Sea and forms the northern arm of land that embraces the gulf or sea of Pohai.

Pohai (Bohai) was the marine gateway to Peking (Beijing), a short distance overland from Bohai ports like Tientsin (Tianjin). Lushun was the northern part of the rib cage that protected the heart of China. The southern part was Weihaiwei -- the object of the next major Japanese campaign in the war.

22 November 1894 Japan and the United States sign a treaty of commerce and navigation, and related memoranda. In the treaty, the US agrees that its extraterritorial status will end in 1899, and Japan agrees to give the US most-favored-nation treatment.

This is just one of several such treaties that Japan was concluding that year with Euro-American states to which it had given extraterritorial status in earlier treaties.

27 November 1894 Japan declines America's peace overtures, which are made on behalf of China. Efforts by Great Britain to mediate on behalf of China in July, when Japan informed China that it also intended to send military forces to Korea, had also failed.

13 December 1894 Haich'eng (�C�� PY Haicheng) occupied. Haich'eng was in Fengtien province. Fengtien city, otherwise known as Mukden (in Manchu), is now Shenyang (�c�z), the capital of Liaoning province. This was the heart of Manchuria, which later became a part of Manchoukuo (���B��).

4-6 March 1895 Niuchuang and Yingk'ou operation operations. Niuchuang (���� E Newchuang, PY Niuzhuang) was a port town a short distance upstream from the mouth of the Liao river, which spills into Pohai bay.

Newchuang had became a treaty port under the terms of the 1858 Treaty of Tientsin (Tianjin), which ended the first phase of the Second Opium War. Britain then opted for a site that was closer to the mouth of the river and deeper. The new site, called Yingkow (�z�� WG Yingk'ou, PY Yingkou), became the treaty port from 1864.

When Japan took Haich'eng, which is further upstream, Chinese forces retreated to Niuchuang. From there they made several attempts to retake Haich'eng.

Japan took Niuchuang and then Yingkou in order to consolidate its possession of the entire coast of the Liaotung peninsula -- from the southern mouth of the Liao river to the mouth of the Yalu.

This was last notable Japanese military action on the Liaotung peninsula during the Sino-Japanese War.

The significance of this action is seen in the wording of Article 2 of Treaty of Shimonoseki. The article cedes "in perpetuity and full sovereignty" three territories, includin (a) the "southern portion of Fengtien province", (b) Formosa (Taiwan), and (c) the Pescadores.

The "boundaries" of the Fengtien territory is described as follows.

|

The line of demarcation begins at the mouth of the River Yalu and ascends that stream to the mouth of the River An-ping, from thence the line runs to Feng-huang, from thence to Hai-cheng, from thence to Ying-kow, forming a line which describes the southern portion of the territory. The places above named are included in the ceded territory. When the line reaches the River Liao at Ying-kow, it follows the course of the stream to its mouth, where it terminates. The mid-channel of the River Liao shall be taken as the line of demarcation. |

The spelling in the place names reflects contemporary English conventions. The English version -- which China and Japan agreed would be the standard for resolving differences in opinion they might have about the meanings of the Japanese and Chinese versions -- was written by John W. Foster, a recently retired former US Secretary of State then working as a consultant for the government of China.

Skip to Shantung

The other part of the terrestrial ribcage that protected Peking from attack by sea from the east was Shantung (Shandong) peninsula. The peninsula juts into the Yellow Sea on the south side of the mouth of the sea (gulf) of Pohai, to the south of Liaotung peninsula on the north side of the mouth.

The Shantung equivalent of Liaotung's Port Arthur was Weihaiwei (�ЊC�q), or Weihai Garrison, known as Port Edward when later under British control. Like Port Arthur, it was on the tip of peninsula, was therefore an extremely strategic locality from the viewpoint of naval operations.

Japan was determined to destroy the remnants of China's naval forces, which had gathered at Weihaiwei. Japan mounted its attack on Weihaiwei from Lushun.

20 January - 12 February 1895 Weihaiwei and nearby areas fall to Japanese ground and naval forces in what was arguably the most difficult operation of the war, considering the logistics and winter weather.

Possession of both Port Arthur and Weihaiwei not only gave Japan control of shipping in and out of Pohai, but from these ports its navy could dominate the Yellow Sea. Japan knew the history of warfare in China, especially its coastal chapters, some very recent.

Japan's possession of the major defensive base on the tip of the Shantung peninsula was also significant because the peninsula is directly north of Taiwan. Warships could easily steam from either Lushan or Weihaiwei to the staits of Taiwan.

Britain had called Lushun "Port Arthur" after a British naval officer took refuge there during the 1860 campaign of the Second Opium War (1856-1860). Lushun was then still mostly a fishing village.

During this phase of the war, joint British and French forces took Chefoo (now Yantai) near Weihaiwei, and Talian (Dalian) near Lushun. This set the stage for seige of Peking, which ended the war -- but not before the Europeans had destroyed the Summer Palace.

Chefoo was a smaller port just to the west of Weihaiwei. Weihaiwei and Chefoo are now parts of Weihai and Yantai cities.

Chefoo -- to return to the Sino-Japanese War -- was the site of the exchange of the instruments of ratification of the Treaty of Shimonoseki, which as the name implies was signed in Japan.

Jump to Penghu

Both Itō Hirobumi (�ɓ����� 1841-1909), Japan's prime minister throughout the war, and Mutsu Munemitsu (�����@�� 1844-1897), his foreign minister, had argued since 1894 that Japan should occupy Taiwan. Itō expressed his opinion that such an operation could be mounted from Weihaiwei.

Japan had been pressing China to cede Taiwan and wished to prevent China from reinforcing its garrisons on Taiwan. As Penghu is situated in the Taiwan straits, naval control of the islands would give Japan an advantage in any attempt by China to keep Japan from taking the islands.

17 March 1895 A provisional truce agreement covered only areas where there had been fighting. Penghu and Taiwan were not included.

20-26 March 1895 The P'enghu (PY Penghu) islands (�O�Η�), called the Pescadores Group in the English version of the Treaty of Shimonoseki, were invaded and occupied with pratically no opposition.

Japan's expeditionary fleet stood off the islands on 20 March 1895 after five-days at sea from Sasebo in Nagasaki prefecture. Bad weather prevented the landing of ground forces until 23 March. Their landing was preceded by some shelling by Japanese ships of shore batteries.

Japanese troops marched on Makung (�n�� J Bakō, PY Magong), the principle port and municipality of the island group, on 24 March but found it mostly deserted. Other strategic sites were taken, also with little resistance, by 26 March.

Truce and treaty

Chinese and Japanese delegates had met in Hiroshima to discuss peace terms as early as early as 1 February 1895. More serious deliberations began at Shimonoseki on 20 March, the day the Japan's expeditionary fleet arrived off Penghu.

During the negotiations, an attempt was made on the life of China's chief negotiator.

20 March 1895 Negotiations between at Shimonoseki.

23 March 1895 Japan commences its invation of the Penghu islands.

24 March 1895 A Japanese man makes an attempt on the life of China's chief negotiator, Li Hung-chang (������ PY Li Hongzhong), shooting him in the face, but he survives. On this same day, Japan occupies Penghu's principle port and municipality.

25 March 1895 An imperial edict (�ْ�) is issued concerning the "distress [caused] the envoy of China" (�����g�ߑ���).

26 March 1895 Japan completes its invation and occupation of Penghu.

27 March 1895 The emperor of China, on account of the wounds suffered by Li, permits an unconditional truce.

30 March 1895 China and Japan agree to an armistice and also to a recess in the negotiations.

10-13 April 1895 Negotiations resume after a brief recess.

Japan somewhat relaxes its demand for indemnities and continental concessions and territory, in view of its demand for Taiwan and the Pescadores, and possibly also out of consideration for the attempt to assassinate Li.

Russia, France, and Germany attempt to dissuade Japan from demanding the Liaotung peninsula. Japan, however, declines to withdraw its demand for the territory.

17 April 1895 China's and Japan's plenipotentiaries sign a peace treaty at Shimonoseki.

21 April 1895 An imperial decree (�ْ�) is concerning the restoration of friendship after the conciliation with China.

23 April 1895 Russia, France, and Germany threaten to evict Japan from Liaotung if Japan did not return the peninsula to China and withdraw its military forces. Japan failed to gain the support of the United States and Great Britain, which chose to remain neutral.

4 May 1895 Japan agrees to return the Liaotung peninsula to China in exchange for additional compensation. Japan notifies concerned parties of this decision the following day. The particulars would be stipulated in another treaty.

8 May 1895 China and Japan exchange instruments of ratification at Chefoo. The treaty had been ratified as signed.

10 May 1895 Kabayama Sukenori (���R���I 1837-1922) appointed the first Governor-General of Taiwan.

10 May 1895 Japan issues an imperial decree (�ُ�) -- making specific reference to the demands made by Russia (�I����), Germany (�ƈ�), and France (�@�N��) -- to the effect that it will return the Liaotung peninsula.

Newspaper reports of this development engenders all manner of discontent among all manner of people in Japan who felt that Japan had won the war but lost the diplomacy. The impression was that Japan was being bullied by Russia, Germany, and France into giving up just rewards for its victory in the war with China. All three of these states -- as well as the United States and Great Britain, which chose to remain neutral in the intervention -- continued, at the time, to have extraterritorial privileges in Japan.

5 June 1895 Russia and Japan exchange declarations in St. Petersburg, confirming the terms of the 1875 Treaty of St. Petersburg, and otherwise pretending to be friends despite Russia's leading role in the Triple Invention.

8 November 1895 China and Japan sign a treaty in Peking (Beijing) in which Japan agrees to retrocede the Liaotung peninsula for a stipulated compensation, and to withdraw its military forces within three months after its payment.

27 December 1895 Japan withdraws the last of its military forces from Liaotung peninsula.

Treaty of Shimonoseki

The Treaty of Shimonoseki was signed ten years nearly to the day after the signing of the Treaty of Tientsin. While the Tientsin treaty had created a sort of bilateral Sino-Japanese guardianship over Korea, with the intent of fostering Korean independence, the Shimonoseki treaty in effect gave Japan full custodial rights over Korea. Again Japan's intent was to foster Korea's independence, albeit as a state that was friendly toward Japan.

The Treaty of Shimonoseki, as signed by the two party states, has Chinese and Japanese versions. The English version is generally attributed to John W. Foster, a former US Secretary of State who participated in the forging of the treaty as a consultant to the Chinese Government.

The entity called Korea in the English version was called respectively �؍� and ���N�� in the Chinese and Japanese versions.

See Nationalization treaties: Texas, Alaska, Chishima, Taiwan, Liaotung, Hawaii, Philippines, and Karafuto on this website for Chinese, Japanese, and English versions of the 1895 Treaty of Shimonoseki and further information about John W. Foster.

Liaotung peninsula

The terms of the Treaty of Shimonoseki, however, set the stage for the chain of events that led to the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905 -- beginning with the Triple Intervention. One month after the treaty was signed, France and Great Britain threatened to evict Japan from Liaotung if Japan did not retrocede the peninsula back to China and withdraw its military forces from the region.

Japan complied, and a month later, on 5 June 1895 (Russian [Julian] 27 May 1895), in St. Petersburg, Japan and Russia signed a declaration to confirm the terms of the 1875 Treaty of St. Petersburg and its attatchments, and otherwise relieve the stress the Triple Intervention had placed on Russo-Japanese relations.

On 8 November 1895, Japan and China had signed the Treaty for Return of Fengtien Peninsula -- aka Treaty of Liaotung Peninsula and Treaty of Peking. And by 27 December Japan had withdrawn its military forces from the territory.

In 1898, however, China leased the peninsula to Russia, which again put Korea in the position of being both a buffer and pawn in the mounting geopolitical rivalry between Japan and Russia. By 1905, Japan and Russia, both hemoraghing from a war that Japan had barely won, were signing a treaty in which Russia's lease over Liaotung was transferred to Japan, along with the South Manchuria Railway and other Russian properties.

During the Russo-Japanese War (1894-1895), Korea had become a protectorate of Japan, shortly after the war it delegated its foreign affairs to Japan -- essentially losing its qualifications as a sovereign state.

See Nationalization treaties: Texas, Alaska, Chishima, Taiwan, Liaotung, Hawaii, Philippines, and Karafuto on this website for Chinese, Japanese, and English versions of the 1895 Treaty of Peking

Taiwan

Taiwan was legally under Japan's control and jurisdiction from May 1895 when the Treaty of Shimonoseki came into effect, to October 1945 when the Republic of China accepted Japan's surrender of Taiwan. It remained legally part of Japan's sovereign dominion, however, until 28 April 1952.

Japan acknowledged that it would lose its control and jurisdiction, and sovereignty, when it signed the Instruments of Surrender on 2 September 1945. It legally lost control jurisdiction, and in effect also its sovereignty, when it surrendered the territory to ROC, and formally lost the territory on 28 April 1952 when the terms of the San Francisco Peace Treaty came into effect.

Under the terms of the 1895 Simonoseki Treaty, Taiwan affiliates would become Japanese unless, within two years, they chose not to leave or otherwise established that they were nationals of another state. Under Japanese law, Taiwanese who had been Japanese nationals lost their Japanese nationality on 28 April 1952.

All the above statements will be disputed by critics from various points of view -- including those as radically different as the view that Taiwan had never legally been part of Japan, and the view that it had never legally become part of the Republic of China.

Nonetheless, history is history, treaties are treaties, and laws are laws -- and no matter of ideological quibbling can undo what was done -- and what happened as a consequence of what was done -- in the name of formal agreements and related actions.

Whether Taiwan and the Penghu islands, as the substantial parts of the Republic of China, are therefore parts of the People's Republic of China, is an issue that involves post 1949 history.

Taiwan-Japanese War

The Sino-Japanese War ended with the enforcement of the Treaty of Shimonoseki. The enforcement of this treaty regarding Taiwan, however, began what I am calling the Taiwan-Japanese War.

It was not, in fact, a "war" (�푈 sensō) but an "operation" (��� sakusen). One popular Japanese publication summarizes the operation, which took place on Taiwan between May and October 1895, in the wake of the Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895), as follows (page 51 of source described below, my translation).

Taiwan operations of tropical diseases and guerrillasAmong [As for] the Penghu islands and Taiwan, which had been exlcuded in the 17 March truce agreement -- Penghu island operation ends 15 April -- [On] Taiwan, which by [because of] the peace treaty had become a new territory [of Japan] while not-yet-captured (���U���̂܂� mi-kōryaku no mama), the Taiwan People-ruled Country [Taiwan Republic] (��p���卑 Taiwan minshukoku) is founded and commences an anti-Japan struggle (�R������ kō-Nichi tōsō) -- In [because of] the violent guerrilla war and tropical diseases, among 26,000 Japanese military forces, [casualties] reach 164 war-dead and 4,642 disease-dead -- With [because of] the fall of Tainan the operation provisionally ends Source�����V���� |

All volumes in the Mainichi series are photo-journalistic records their theme and period. This volume is dedicated to Japan's two biggest interenational wars of the Meiji period (1868-1912).

The series is not nationalistic but merely reflects the tendency in all countries to focus on their own loses and casualties. Still, the cited volume amply shows and comments on the devastation that Japan's military forces sometimes wreaked in its campaigns to suppress resistance against Japan's governing of Taiwan.

One picture shows several guerrilla bodies and a disembodied head in Tainan, where supporters of the Taiwan Republic resisted to the end. The caption notes that "the Japanese army carried out total slaughter [butchery, massacre] (�O��I�ȎE�肭 tettei-teki-na satsuriku) in the guerrilla war" -- and that "the number of abandoned bodies on the entire island climed to around 8,000" (page 51).

Unrecognized government

The "war" that continued in Taiwan is called an "operation" (���) in Japanese. The self-declared "Taiwan Republic" was somewhat of an embarrassment for China, which could not in good faith have recognized the government, or otherwise reciprocated its recognition of China as its suzerain. The last thing China wanted was to give Japan pretext for regarding China as a belligerent in what was being called an "operation" (���).

The United States and Great Britain, which had mediated between China and Japan -- and even Russia, Germany, and France, which would force Japan to return the Fengtien peninsula to China -- recognized that Japan was entitled, by the Treaty of Shimonoseki, to take possession of Taiwan. In other words, the actions that Japan began to take regarding Taiwan, immediately after the end of the war, were legal in the world's eyes.

China makes preparations to defend Taiwan

China, hearing rumors that Japan would demand Taiwan as part of the settlement, sent troops to the island and otherwise made preparations to defend the territory. During the final stages of peace negotiations, though, Japan invaded and occupied the Penghu islands.

When singing the Treaty of Shimonoseki, China accepted the loss of Taiwan and the Penghu islands. And as soon as the treaty had come into force, Japan formally created a Government-General and appointed a Governor-General to head it.

Some Chinese generals on Taiwan, and other Taiwanese who had been preparing to defend the island, however, chose not to recognize the cession of the island and the Japanese military government, and declared the establishment of what they called the "Taiwan Republic" (��p���a�� J Taiwan kyōwakoku, WG T'aiwan kunghekuo, PY Taiwan gongheguo) -- a nominally independent state under Chinese suzerainty.

The Minister of Foreign Affairs of this new state had recently been "the military attache at the Chinese Legation in Paris" and had just arrived in Taiwan via Peking and Tientsin (Takekoshi 1907:83). It is not unlikely that some other Chinese officials were also partly behind the movement to create the republic.

Japan takes possession of Taiwan

10 May 1895 Kabayama Sukenori (���R���I 1837-1922) appointed the first Governor-General of Taiwan.

23-25 May 1895 Founding in Taipei of the "Formosan Republic" as it was called in English, and �i�s���嚠 (T'aiwan minchu kuo) or "Taiwan democratic state" in Chinese. Some writers refer to the entity as "Taiwan Republic" (�i�s���a��, ��p���a�� J Taiwan kyōwakoku, WG T'aiwan kunghekuo, PY Taiwan gongheguo).

For examples of stamps issued in the name of this government, and some frankings showing its English name and dates corresponding with the government's final weeks, see 1895 Formosan Republic stamps in the "Taiwan as part of Japan" section of the article on "The empire of postal services" in "The Detritus of Empire" feature.

The Chinese version of the Formosan Republic's declaration of independence does not survive. An English version appears to have survived in the body of a contemporary report by an American correspondent in Taiwan.

Wikipedia "Republic of Formosa" articlesA Wikipedia article called "Republic of Formosa" refers to the entity as the "Republic of Formosa". It gives the characters �i�s���嚠 and ��p���卑, reads them in Pinyin as "Taiwan minzhuguo", and explains that they literally mean "Democratic State of Taiwan". The Chinese version gives �i�s���嚠 (WG T'aiwan minshukuo) and the Japanese version ��p���卑 (J Taiwan minshukoku).The English Wikipedia article cites the text of the English version of the Taiwan Republic's so-called "Declaration of Independence". The cited text refers to the new entity as the "Republic of Formosa" and to the people as the "People of Formosa". It also accuses Japan of having "affronted China by annexing our territory of Formosa" and there is a sense of urgency as "the Japanese slaves are about to arrive" and if nothing is done Formosa will become a "land of savages and barbarians" (retrieved 11 September 2009). Wikipedia attributes the English text to "Davidson, J. W., The Island of Formosa, Past and Present, London, 1903", pages 279-280. This apparently refers to the following work, which I have not examined. Source (Unconfirmed) James W. Davidson |

29 May 1895 Japan begins landing ground forces on Taiwan to suppress efforts by Chinese and others to prevent its governmental takeover.

1 June 1895 Japanese forces take and occupy begins landing ground forces on Taiwan to suppress efforts by Chinese and others to prevent its takeover governmental takeover.

3 June 1895 Japanese forces commence their attck on Keelung (Kelung, Chilung), on the northern tip of Taiwan.

3 June 1895 While Keelung is under siege, a formal ceremony for transferring sovereignty of Taiwan and the Pescadores from China to Japan takes place at sea, off the coast of Taiwan, between Li Ching-fang (���S�F), Li Hung-chang's nephew and adopted son, and Governor-General Kabayama Sukenori.

7-8 June 1895 Japanese forces enter and take control of Taipei (��k) , the capital of Taiwan, to the south of Keelung. By this time, the president of the so-called "Taiwan Republic" has fled to China. A new leader assumes the mantle, and with remnants of the rebel forces, establishes the republic of the Taiwan Republic in Tainan (���), on the southwest coast of Taiwan.

21 October 1895 Japanese forces occupy Tainan, where Japan had sent ground forces to help suppress resistance to its rule.

23 November 1895 Fall of Taiwan Republic at Tainan.

Return of Liaoting peninsula

The Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895, between Japan and China, was settled by the Treaty of Shimonoseki. China agreed, in Article 2 of the treaty, to cede Japan "in perpetuity and full sovereignty" (a) the southern part of Fengtien province, meaning the Liaotung peninsula and associated islands, (b) Formosa and associated islands (Taiwan), and (c) the Pescadores Group (Penghu).

A month after the treaty came into force, international pressure forced Japan to retrocede Liaotung back to China, thus voiding this provision in the treaty. Taiwan and Penghu, however, were internationally recognized as having become parts of Japan.

Taiwan (including Penghu) was the first territory a foreign state had ceded to Japan, which Japan had not previously regarded as part of its inherent dominion. Taiwan was not a dependency or a colony in the ordinary sense of either term, but an integral part of Japan's sovereign territory.

By the end of 19th century, the history of contacts between people in Japan and the islands of Taiwan -- incidental to shipwrecks, marine trade and piracy, and political and military adventurism -- went back about a millennium. The late 16th and early 17th centuries witnessed direct contact -- in the form of landings, explorations, and failed attempts at settlement -- intiated by Japanese political and military adventurists.

In the middle of the 16th century, Taiwan -- known by a number of names at various times in the various languages of East Asia and the Pacific -- came to be called "Ilha Formosa" (Island beautiful) in Portuguese. From the early decades of the 17th century, Taiwan came under Dutch and Spanish influence, but by the end of the century it was under Chinese suzerainty.

In the middle of the 19th century, Taiwan became a source of diplomatic friction between foreign states and China, because of the treatment their nationals had received by inhabitants of Taiwan when shipwrecked along its coasts. In 1874, Japan sent an expeditionary military force to Taiwan to punish a group of aborigines responsible for the killing of a number of Ryukyu fishermen who shipwrecked in south in 1871.

The Pescadores, and northern parts of Taiwan, became battlegrounds during the Sino-French (Franco-Chinese) War of 1884-1885, essentially over Vietnam. Though victorious in some of the battles involving the islands, France evacuated its footholds there at the end of the war.

During the Sino-Japanese War, Japan's prime minister and minister of foreign affairs, among others, coveted Taiwan for the usual reasons -- its natural resources and its proximity to Okinawa. For military and other security reasons, too, Taiwan was an obvious asset to Japan. However, it is highly unlikely that Japan would have acquired Taiwan had there been no Sino-Japanese War, which essentially involved rivalries in Korea.

Government-General of Taiwan

When Taiwan became part of Japan in 1895, Japan did not immediately know how it should govern the territority under its 1890 Constitution.

In principle Taiwan was part of the emperor's sovereign dominion. However, Taiwan was not automatically reached by laws that applied to the prefectures. The emperor, though, was empowered not only to sanction and promulgate laws consented to by the Imperial Diet, but to issue ordinances under his own authority.

Apart from the usual transitory measures inevitably required to effect transfers of state jursidictions, Japan faced widespread civil unrest and rebellion in Taiwan that made effective governance impossible until such resistance to its authority was suppressed. Some of the challenges to Japanese authority were specifically anti-Japanese. Other disturbances represented continuations of the sort of disorder that had plagued Chinese suzerains for more than two centuries.

Japan began its rule of Taiwan with the establishment of the Government-General of Taiwan (GGT) in Keelung (� SJ Kiryū, Kiirun, WG Chilung, PY Jilong) in May 1895. The GGT moved to Taipei (��k) in June and branch offices were set up in various districts with police departments.

From August 1895, GGT shifted to a military administration, meaning that Taiwan was essentially under martial law. This shift facilitated the needs of the new government to suppress anti-Japanese rebellions.

GGT shifted to a nominally civil administration from 1 April 1896, the first day of the fiscal year of Meiji 29. This is the datum for the start of compilation of many kinds of social statistics.

As GGT expanded its operations, its agencies were frequently reorganized. The police, who were responsible for suppressing local uprisings and otherwise establishing public order and safety, underwent many organizational changes during the first two decades.

In August 1915, "managing barbarian" (����) operations were shifted to the police. A police bureau (�x����) was established within GGT in July 1919.

Diet laws empowering the Governor-General of Taiwan

Government-General of Taiwan (��p���{ Taiwan Sōtokufu) means "Headquarters [seat, office] (�{) of the governor-general (����) of Taiwan". The first several Governor-Generals of Taiwan (��p���� Taiwan Sōtoku) were all military officers. Though accountable to the prime minister and the emperor, they had plenary powers over the territory with regard to its civil and military administration, and were empowered to give military orders -- until 1919, from which time GGT was headed mostly by men with civilian backgrounds.

Note Unless otherwise noted, the promulgation dates shown for laws are the dates the original laws or their revisions were published in the Official Gazette (Kanpō). Otherwise the "seal" date is shown, meaning the date the emperor affixed his seal to the law. Most laws appeared in the Official Gazette the day after they received imperial sanction.

The first Governor-General of Taiwan, Kabayama Sukenori (���R���I 1837-1922), had been an army general and a navy admiral before becoming Minister of the Navy and retiring in the early 1890s. He returned to duty during the Sino-Japanese War and commanded the forces that began to occupy Taiwan. Kabayama headed GGT from 10 May 1895 to 2 June 1896.

Kabayama's first challege

Kabayama's first challenge was to suppress uprisings led by Chinese officials on Taiwan and others who rejected the terms of the Shimonoseki Treaty and attempted to prevent Kabayama from establishing Japan's rule over the territory that according to the treaty belonged to Japan. It took Kabayama bout half a year to secure Taiwan to the point that he could established offices of his government in the island's major cities.

Faced with civil unrest and even rebellion, Kabayama argued that he needed the authority to directly govern the territory with only the emperor's sanction and promulgation of laws his government deemed necessary. In other words, the Goverment-General of Taiwan should function the same as the Imperial Diet, with the mediation of the Prime Minister. Only the Prime Minister would stand between the GGT and the emperor.

Inaugural legislation

The Governor-General of Taiwan's position held sway. And on 31 March 1896, the emperor promulgated Imperial Diet Law No. 63, entitled "Law concerning laws and regulations to be enforced in Taiwan" (�i�s�j�{�s�X�w�L�@�߃j萃X���@��), giving the GGT three years of legislative authority, after which the Diet would review his mandate. Edward I-te Chen aptly calls this "delgated authority" (Chen 1984: 284, 252, and others).

The GGT's three-year mandate was thrice renewed, in 1899 (Law No. 7, promulgated 8 February, effective through 31 March 1902), 1902 (Law No. 20, promulgated 20 March, effective through 31 March 1905), and 1905 (I have not yet confirmed this law).

A new version of the 1896 law, enacted in 1906 (Law No. 31, promulgated 11 April, effective from 1 January 1907), extended the mandate to five years (effective through 31 December 1911).

The five-year mandate was twice renewed, in 1911 (Law No. 50, promulgated 29 March 1911 [seal], effective through 31 December 1916), and in 1916 (Law No. 28, promulgated 17 March 1911 [seal], effective through 31 December 1921).

Early Governor-Generals and Civil Administrators

Kabayama was replaced by a succession of army officers, including Katsura Tarō (�j���Y 1848-1913) from 2 Jun2 1896 to 14 October 1896, Nogi Maresuke (1849-1912) from 14 October 1896 to 26 February 1898, and Kodama Gentarō (���ʌ����Y 1852-1906) from 26 February 1898 to 11 April 1906.

The director of civil administration under both Kabayama and Katsura was Mizuno Jun (���쏅 1850-1900), who held the title from 21 May 1895 to 20 July 1897. Nogi replaced Mizuno with Sone Shizuo (�]���Õv), who served in the post from 20 July 1897 to 2 March 1898. Kodama replaced Mizuno with Gotō.

|

Early Taiwan Governor-Generals and Directors of Civil Affairs |

|||

|

Governor-General |

Period in office |

Civil Administrator |

Period in office |

|

���R���I |

1895-05-10 |

���쏅 |

1895-05-21 |

|

�j���Y |

1896-06-02 |

||

|

�T�؊�T |

1896-10-14 |

�]���Õv |

1897-07-20 |

|

���ʌ����Y |

1898-02-26 |

�㓡�V�� |

1898-03-02 |

|

���v�ԍ��n�� |

1906-04-11 |

�j�C�� |

1906-11-13 |

|

Iwai died in office. Three other men succeeded him as Civil Administrator during Sakuma's tenure as Governor-General. |

|||

Jurisdiction and sovereignty

Jurisdiction and sovereignty are not the same.

A state can be ceded a territory in a treaty, and thereby have sovereignty, but not yet have control and jurisdiction. This was the case with Taiwan in 1895, for the several months it took Japan to gain control over the territory after it became part of Japan's sovereign dominion. Without control, there can be no effective jurisdiction.

Or a state can lease territory from another state -- or capture territory during a war, or occupy territory after a war -- and thereby establish control of, and jurisdiction over, a territory without possessing sovereignty. This is the more common case. China retained sovereignty over Japan's Kwantung Leased Territory from 1905-1945, and Japan retained sovereignty over Okinawa under US administration from 1945-1972.

Under the terms of the general surrender, Japan agreed that it would lose Taiwan. However, Taiwan remained under Japanese control and jurisdiction until the territory was formally surrendered to ROC authorities representing the Allied Powers. Also under the terms of surrender, Japan delegated its sovereignty to the Allied Powers, and in effect lost its sovereignty over territories like Taiwan pending treaty agreements. Under the terms of surrender, ROC assumed that it would have sovereignty over the territory from the moment of the surrender in 1945. But in a sense, Japan retained residual sovereignty over Taiwan until the terms of the San Francisco Peace treaty came into effect in 1952.

Difference between Okinawa and Taiwan

The crucial difference between Okinawa and Taiwan is not the manner in which they came to be occupied and controlled by other states -- Okinawa by the United States, Taiwan by the Republic of China representing the Allied Powers. More important was the fact that Japan abandoned its sovereignty over Taiwan but not overe Okinawa. Hence Japan continued to have residual sovereignty over Okinawa until it was returned to Japan's control and jurisdiction in 1972.

In 1945, the United States invaded and occupied Okinawa prefecture in the process of pursuing the war it had declared against Japan. After the US captured the islands affiliated with the prefecture, and a few nearby islands that were part of Kagoshima prefecture, the US placed all of these islands under a military government (�R�{ gunpu).

The Instruments of Surrender provided that these islands would remain under a US military government, and hence they were not part of "Occupied Japan" -- which, to some extent, remained under Japan's control and jurisdiction. Legally, the Ryukyu islands under US military and civil administration, and Occupied Japan under GHQ/SCAP, were different entities. Occupied Japan was the territorial foundation for the "Japan" that regained its sovereignty when the San Francisco treaty came into effect.

From 15 December 1950, General MacArthur, as Commander in Chief, Far East Command, replaced the military government of the Ryukyu islands with a nominally civil administration (����) called the United States Civil Administration of the Ryukyu Islands (USCAR) (����������{) -- or simly Office of the Civil Administrator (�������{).

USCAR was headed by a governor (����) and deputy governor (������). In principle, the Commander in Chief, Far East Command, in Tokyo, was the Governor of the Ryukyus, while the Commander in Chief, Ryukyus Command (�ɓ��R�i�ߊ�), in the Ryukyus, was the Deputy Governor. Under the Deputy Governor was a Civil Administrator (������).

US Executive Order 10713 of 1957 replaced the Governor and Deputy Governor by a High Commissioner (�����ٖ���). Six US Army lieutenant generals served as High Commissioner from 5 June 1957 through 15 May 1972, when Okinawa reverted to Japan.

Diet tightens harness on Taiwan governor

The first several Governors-General of Taiwan were military officers. Sweeping reforms, introduced by the Imperial Diet in 1921, included the appointment of the first civilian GGT.

Shift to "civilian control"

On 15 March 1921, a new "Law concerning laws and regulations to be enforced in Taiwan" (��p�j�{�s�X�w�L�@�߃j�փX���@��) was promulgated (Law No. 3). This law, which came into effect from 1 January 1922, considerably curtailed the legislative authority of the GGT by allowing him to formulate laws only when interior laws could not be effectively applied. "In other words," as Edward I-te Chen writes, "after 1921 the application of Diet-enaced laws to Taiwan became a principle rather than an exception" (Chen 1984: 256)."

The 1921 law also extended the efficacy of laws and regulations previously issued by the Governor-General of Taiwan under Law No. 63 of 1896 and Law No. 31 of 1906. The law lost its effectiveness upon the enforcement of the San Francisco Peace Treaty on 28 April 1952.

1921 Law concerning laws to be enforced in Taiwan

Law No. 3 of 1921

Promulgated on 15 March 1921

Enforced from 1 January 1922

Lost effectiveness on 28 April 1952 due to enforcement of [San Francisco] Peace Treaty with Japan (Treaty No. 5 of 1952)

��p�j�{�s�X�w�L�@�߃j�փX���@�� (�吳10�N�@����3��)

�����@�@���m�S�����n�ꕔ����p�j�{�s�X�����v�X�����m�n���߃��ȃe�V���胀

2�@�O���m�ꍇ�j���e�������n�����m�E���A�@����m���ԑ��m���m�����j�փV��p����m����j�������გ�݃N���K�v�A�����m�j�t�e�n���߃��ȃe�ʒi�m�K�胒�׃X�R�g����

�����@��p�j���e�@�����v�X�������j�V�e�{�s�X�w�L�@���i�L���m���n�O���m�K��j�˃���L���m�j�փV�e�n��p����m����j�����K�v�A���ꍇ�j������p���m���߃��ȃe�V���K��X���R�g����

��O���@�O���m���߃n�喱��b���o�e���ك����t�w�V

��l���@�Վ��ً}���v�X���ꍇ�j���e��p���n�O���m�K��j�˃��X���j�����m���߃����X���R�g����

2�@�O���m�K��j�˃����V�^�����߃n���z�㒼�j���ك����t�w�V���ك����T���g�L�n��p���n���j���m���߃m�����j���e���̓i�L�R�g�����z�X�w�V

����@�{�@�j�˃���p���m���V�^�����߃n��p�j�s�n�����@���y���߃j�ᔽ�X���R�g�����X

����

1�@�{�@�n�吳�\��N�ꌎ��������V���{�s�X

2�@������\��N�@����Z�\�O�����n�����O�\��N�@����O�\�ꍆ�j�˃���p���m���V�^�����߃j�V�e�{�@�{�s�m�ی��j���̓��L�X�����m�j�t�e�n�����m�����]�O�m��j�˃�

Family registers

As was the practice in all of earlier incorporations of new territories into its sovereign dominion, Japan quickly adapted parts of the Interior Family Registration Laws to the new territory in the process of Interiorizing Territorial common laws.

Family registers in Taiwan

To be continued.

Hundreds of laws and ordinances were promulgated to facilitate the governing of Taiwan -- after the Japanese government accepted the arguments of the Governor-General of Taiwan that he, and not the Imperial Diet, should mediate between the Emperor and Taiwan.

A series of ordinances in 1932 and 1933 created specific registation laws for Taiwan, such that Taiwan subjects would be registered in Taiwan registers, and interior subjects residing in Taiwan would be registered in interior registers. Marriage between a Taiwan subject and an Interior subject would effect the transfer of one subject to the other subject's register.

To be continued.

In 1896 GGT had issued a notice (No. 8) called "Notice concerning Taiwan family registers" (��p�ːЃj�փX������) to deal with household census registration.

Ordinances concerning civil and penal matters were issued in 1898.

In 1905, GGT Ordinance No. 95, called "Taiwan Household Census Regulations" (��p�ˌ��K��), provided that the registers of interior and Taiwan subjects be separated by region.

In 1908, GGT issued Decree No. 11, "Taiwan Civil Matters Decree" (��p������).

Imperial Ordinance No. 361 of 1932, promulgated on 26 November 1932, was titled "Matter of causing district governors, police precinct chiefs, police sub-precinct chiefs, and sub-cho chiefs to handle affairs concerning household registers of [Taiwan] Islanders" (�{���l�m�ːЃj�փX���������S��A�x�@�����A�x�@���������n�x�������V�e�戵�n�V�����m��).

This ordinance made the following provisions (my structural translation).

|

Matter of causing district governors, police precinct chiefs, police sub-precinct chiefs, |

|

|

��p�j���e�{���l�m�ːЃj�փX�������n�S��A�x�@�����A�x�@���������n�x�����V���s�t ��p���n�K�v�g�F�����g�L�n�{�߃j�˃��S��A�x�@�����A�x�@���������n�x�����m�E�����x�����n�x����j�㗝�Z�V�����R�g���� �ːЎ����n��ꎟ�j���e�S�����A�x�@���A�x�@�������n�x���m���ݒn���NJ��X���m�����n�����V���ēV��j���e��p���V���ēX ���� �{�ߎ{�s�m�����n��p���V���胀 |

As for administration concerning the household registers of [Taiwan] Islanders, in Taiwan, district governors, police precinct chiefs, police sub-precinct chiefs, and branch-cho heads shall conduct them. The Taiwan Governor-General, when recognizing necessity, pursuant to this ordinance, shall enable district governors, police precinct chiefs, police sub-precinct chiefs, and branch-cho heads to delegate the tasks [work] [concerning household register] to police inspector or assistant police inspectors. As for household register administration, primarily the [provincial] governor or the cho head who has jurisdiction over the locality of the district hall, police precinct, police sub-precinct, or branch-cho shall supervise them; [and] secondarily the Governor-General of Taiwan shall supervise them [the provincial governors and cho heads]. Supplementary provision As for the day of enforcement of this ordinance, the Governor-General of Taiwan shall determine it. |

1932 (GGT Decree No. 2)

Matter concerning registers of islanders (�{���l�m�ːЃj�փX����)

1933 (GGT Ordinance No. 8)

Matter concerning family registers of islanders (�{���l�m�ːЃj�փX����)

���a8�N1��20����p���{�ߑ�8��

Taiwan Governor-General Ordinance No. 8 of 20 January 1933

Civil Code

Forthcoming.

Nationality in Taiwan

The Treaty of Shimonoseki of 1895 provided two years within which inhabitants of Taiwan and Penghu -- and Liaotung, retroceded later that year -- were free to leave. But should they remain, Japan would have the option of regarding them its subjects hence nationals. Naturally Japan would have to regard people in the territories who were legal affiliates of other states it recognized as aliens. Most inhabitants of any degree of continental Chinese descent, however, were natives of the island in the sense they had been born there, and because they were totally settled in Taiwan they stayed and became Japanese subjects.

Japan's first Nationality Law did not come into effect until 1899, but as soon as it did, it and several other laws were made applicable to Taiwan by an imperial ordinace [edict] (���� chokurei).

The Nationality Law was promulgated on 16 March and enforced from 1 April 1899. The law was extended to Taiwan by Imperial Ordinance No. 289 of 1899, promulgated on and enforced from 21 June 1899.

The 1890 Constitution spoke of "Japan subjects" (���{�b�� Nihon shinmin), not "Japan nationals" (���{���� Nihon kokumin), and not "Japanese" (���{�l Nihonjin), though as legal expressions all three terms were essentially synonymous. The Nationality Law, satisfied the constitutional requirement for a law that defined the conditions for being a subject of Japan, literally determined the conditions for being Japanese.

Note that extending the Nationality Law to Taiwan did not make Taiwanese nationals of Japan. The Nationality Law applies only to registers which are assumed to have already been incorporated into Japan's sovereign dominion.

Taiwanese became Japanese subjects and nationals as an effect of the Shimonoseki Treaty. Japan naturally regarded inhabitants who had remained as its subjects hence nationals. Already there were conflicts regarding nationality claims on the part of some Taiwanese who had gone to China and represented themselves as Japanese. China regarded some of these individuals as Chinese but had no legal provisions for regarding them so.

By 1898, Japan had a Rules of Laws, which determined applicable laws, Article 1, Paragraph 2 of which provided that "Regarding Taiwan, Hokkaidō, Okinawa prefecture, and [certain] other insular lands [places] [that are part of Japan's sovereign territory], it shall be possible for [the government] to determine a special [specific] enforcement date by imperial ordinance" (my translation). The regionality of the listed entities derived from the fact that they were entirely or partly overseen by authorities other than the Ministry of Interior, which oversaw the prefectures of Honshō, Shikoku, and Kyūshū.

Hence by the time the 1899 Nationality Law was applied to Taiwan, Taiwan had already become part of Japan's sovereign dominion, and Taiwanese were already regarded as Japan's subjects and nationals. This had to have been the case, for Japan's Nationality Law has no provisions for declaring that people already in registers affilated with Japan's sovereign dominion are Japanese. It determines only only gain and loss of nationality related to registers already regarded as Japanese.

In this regard, the 1899 Nationality Law was merely a statuatory codification of customary rules that had already been determing Japanese status, and which would have continued to determine Japanese status without a nationality statute. The 1890 Constitution required a subjecthood statute, and the writers of the Constitution had in the nationality section of the Civil Code, which was promulgated but not enforced 1890.

In the meantime, the 1890 Constitution did not nullify customary status laws, which had been operating from 1871 and 1873, and rested on centuries of written and customary household registration and family law practices. Not only did the earlier Meiji laws continue to operate until enforcement of the Nationality Law, but they continued to operate afterward, as the Nationality Law was predicated on their operation.

The Nationality Law was did not begin to operate in Karafuto until 1924, yet there was no difficulty in determining who was a Japanese subject, as territorial registers and the rules that applied to register status had the same effect. The Nationality Law was never applied to Chosen, where written and customary laws and practices determined who was territorially affiliated with Chosen, hence logically a subject and national of Japan, since Chosen was part of Japan's sovereign dominion.

Imperial Ordinance No. 289 of 1899, promulgated in the Official Gazette (���� Kanpō) on 21 June 1899, provided for the enforcement, in Taiwan, of the Nationality Law and four other 1899 laws (Tashiro 1974: 848-849).

The title of Law No. 289 of 1899 was as follows.

���m�ӔC�j�փX���@���A�����O�\��N�@����\�O���A���Ж@�A�O���͑D��g���m�ߕߗ��u�j�փX�������@�y�����O�\��N�@�����\�l������p�j�{�s�X���m��

Shikka no sekinin ni kan suru hōritsu, Meiji 32-nen hōritsu Dai 53 gō Kokusekihō, Gaikoku kansen noriai-in no taiho ryūchi ni kan suru enjo hō oyobi Meiji 32-nen hōritsu Dai 94 gō o Taiwan ni shikō suru no ken

Matters of enforcing in Taiwan the Law Concerning Responsibility for Losing [control of] a Fire, Law No. 53 of 1899, the Nationality Law, the Support Law Concerning the Arrest and Detainment of Foreign Vessel Crewmen, and Law No. 94 of 1899

All these laws were 1899 acts and they are listed in the title of the above act in the order of their 1899 law number. The fire responsibilty law was No. 40. I am unable to identify No. 53. The Nationality Law was No. 66 and the foreign vessel crew law was No. 68. Law No. 94 concerned the rights of persons who had lost their Japanese nationality (���Бr���҃m�����j�փX���@�� Kokuseki sōshitsusha no kenri ni kan suru hōritsu).

See 1899 Nationality Law: "The conditions necessary for being a Japanese subject" for this law and its revisions through 1947.

Dual nationality after succession

China under the Ching Dynasty did not have a nationality law until 1909. However, not until the 1929 Nationality Law of the Republic of China was it possible for Chinese subjects to voluntaritly renounce Chinese nationality. Even after renunciation became possible, China was inclined to recognize anyone with a Chinese father as Chinese, and to regard Chinese subjecthood as inalienable. (For a general overview of Chinese nationality during this period, see Chiu Hungdah, "Nationality and International Law in Chinese Perspective (with special reference to the period before 1950 and the practice of the administration in Taipei)", Chapter 2, pages 27-64, in Ko Swan Sik (editor), Nationality and International Law in Asian Perspective, Dordrecht: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1990.

This meant that some people on Taiwan who had been Chinese -- who, in accordance with the Treaty of Shimonoseki in 1895, did not leave Taiwan, or did not otherwise clearly establish that they were Chinese subjects -- became Japanese in Japan's eyes, but continued to be regarded as Chinese in China's eyes.

Apparently some such individuals took advantage of their double status. George H. Kerr, in Formosa: Licensed Revolution and the Home Rule Movement, 1895-1945) (Honolulu: The University Press of Hawaii, 1974), makes this observation about the impact of the change in sovereignty of Taiwan on neighboring Fukien (page 41, underscoring and bold emphasis mine).

|

Amoy was restless under the growing pressure [of political reaction on Taiwan to Japanese rule and of Japanese interests in Fukien]. Formosans were coming into Fukien in large numbers, creating serious problems. Some who had found the Japanese administration intolerable made this the first line of retreat; those who considered themselves altogether Chinese turned their backs upon the island of their birth and cut all ties with it. Some set themsleves up in business in Fukien but kept alive the ties of clan and family across the Strait. Many exploited the advantages of dual citizenship. Peking considered all Chinese inalienable subjects of the Middle Kingdom because of race, language, and culture, but those who had opted for Japanese citizenship after May 1895, could also claim official Japanese protection in China if they maintained registration on Formosa and carried proper papers when abroad. Among these "dual citizens" were criminal elements who had been rounded up on Formosa and given a choice between prison there or service in China as subsidized agents, working as narcotics peddlers, as spies, or as disruptive troublemakers creating "incidents" leading to Japanese "protests," demands, and interventions. |

Kerr uses the words "citizenship" and "citizen" in a very American way, unmindful that neither Japanese nor Chinese law defined "citizenship" or "citizens". People who possessed Japan's nationality were "subjects" (�b�� shinmin) in relation to the sovereign emperor, and "nationals" (���� kokumin) in relation to the state's demographic nation.

It is not, in any event, a problem of dual nationality, as a problem of the existence and enforcibility of laws that determined which country's laws applied in the case of dual nationals. Under such laws, dual Japanese-Chinese nationals would have been treated as Japanese in Japan (including Taiwan) and Chinese in China.

Japan's 1899 Nationality Law made no provisions for renunciation -- until 1916, when Japan was diplomatically forced to legally facilitate requests by Japanese with another nationality to renounce their Japanese status. China's earliest nationality laws were based on Japan's 1899 law before its 1916 revision. The Nationality Law adopted in 1929 by the Republic of China reflected the renunciation provisons of the revised Japanese law.

One major difference between Japan's 1899 law and China's 1929 law concerned loss of nationality when naturalizing in another country. Japan's law provided that Japanese who volunarily acquired the nationality of another country would lose their Japanese nationality, whereas China's law allowed renunciation rather than mandate loss. Japan, in other words, did not attempt to cling to its nationals as much as China. Given that Japanese and Chinese nationality were mainly gained through descent at time of birth, Japan may be seen to be less insistent on demanding loyalty simply because of descent. In other words, Japan's view of "blood" was not nearly as determinist as China's.

Dual nationals during 1920s

Three decades later, during the late 1920s, Taiwan was restless with movements for local autonomy, some nativist or nationalist, others proletarian. Police broke up demonstrations and arrested leaders who advocated so-called "home rule" (����). Communists and socialists generally were objects of police harrassment.

During the late 1920s in China, the rivalry between communists and nationalists was heating. There were also clashes between war lords. Nationalist campaigns against the war lords who had gained control of the Chinese government in Beijing resulted in the resurrection of the Republic of China in 1928.

The political environment in Taiwan, and events on the mainland, inspired many Taiwanese of Chinese descent to leave the island. Some explored communist or nationalist dreams on the mainland. Others studied abroad, in Russia or the United States, if not in the interior.

The mainland, of course, was not a particularly peaceful place to be in the late 1920s. Being a Chinese with Japanese nationality, though, had advantages, according to Kerr (Ibid., page 142)

|

In all, about eight thousand Formosans living in continental China at this time took the trouble to register at the Japanese consulates in order to enjoy the benefits of dual citizenship in a country ruled by generals and torn by civil war. It is not known how many more gave up all claims to protection as Japanese subjects and faded into quiet anonymity as businessmen lost in the great cities. Scores of young men left Formosa in this decade to study abroad -- in Japan proper, in China, and in the United States, Canada, or Europe, after which they returned to teach in China or to enter the Nationalist Chinese government service. . . . |

Restoration of Chinese nationality after World War II

The Government-General of Taiwan formally surrendered to the Republic of China in Taihoku on 25 October 1945. The city instantly became Taipei (Taibei). The day was declared Taiwan Restoration Day [Taiwan Guangfujie]. It continues to be celebrated, but with less enthusiasm and no longer as a national holiday. Taiwanese who have opposed ROC's rule of Taiwan do not recognize the term "restoration" [guangfu].

12 January 1946 decree Within three months after accepting Japan's surrender, the ROC government issued a decree that provisionally restored Chinese nationality to the people of Taiwan from 25 December 1945. The decree appears to have said this (Chiu Hungdah, op. cit., page 53, citing Hungdah Chiu (editor), China and the Question of Taiwan: Documents and Analaysis, New York: Praeger, 1974, page 204; corrections and notes are mine).

|

The people of Taiwan are people of our country. They lost their nationality because the island was invaded by an enemy [Note 1]. Now that the land has been recovered, the people who originally had the nationality of our country shall, effective on 25

|

Becauase Taiwanese were not held to have voluntarily lost their nationality, they were regarded as having all the rights of Chinese who had never lost their nationality, unlike those who regained their nationality after voluntarily losing it (Chiu, ibid., page 53).

The 22 June 1946 regulation, promulgated by the Executive Yuan, restored Chinese nationality to "overseas Taiwanese" or people with Taiwan registers -- retroactive to 25 October 1945, the date of ROC's "seizure" of Taiwan -- meaning the date ROC had accepted Japan's surrender of the territory. The regulation was titled "Law regulating the disposition of nationality of Taiwan sojourners residing outside" (Big5 �݊O�䋡���Й|��辦�@, GB 在外台侨国籍处理办法, JIS �݊O�䋡���Џ����ٖ@).

Taiwanese residing overseas could recover their nationality by registering at a Chinese embassy or consulate. This would then obligate the host country to treat the person as any other national of the Republic of China. Taiwanese who did not wish to recover their Chinese nationality were given until 31 December 1946 to notify an ROC mission or representative of their wishes (Chiu, ibid., page 54).

De jure loss of Japanese nationality

All the above not withstanding, Taiwanese did not formally lose their Japanese nationality until the de jure retrocession of Taiwan to ROC was effected on 28 April 1952. This was the date the Treaty of San Francisco came into force, and the date ROC signed its own treaty of peace with Japan in Taipei.

Mixed marriage and adoption alliances in Taiwan

By "mixed" alliances I mean alliances of marriage and adoption between people in Taiwan of different register affiliations. Such alliances involved the following three tiers of "mixture".

International The parties were of different nationality (���� kokuseki) affiliations. For example, one party was "Japanese" (Interiorite, Chosenese, Taiwanese) and the other was "alien" (British, Chinese, Dutch, whatever).

Interterritorial The parties were of different territorial (subnational) affiliations within Japan. For example, Interiorite-Taiwanese, Interiorite-Chosenese, Taiwanese-Chosenese.

Intraterritorial The parties were of different subterritorial status -- i.e., different "clan" (�푰 shuzoku) statuses. "Interclan" alliances would include, for example, Cantonese-Fukienese, Cantonese-Aborigine, Ami-Paiwan, whatever.

The possible mixtures increase as tiers are crossed. For example, a Chinese-Aborigine alliance would involve an alien status with a Japanese of Taiwanese sub-territorial status. And an Interiorite-Atayal alliance would involve two people of different territorial statuses, one of which was also of a Taiwanese sub-territorial tribal status. Whatever.

What customary laws, statute laws, ordinances, or other criteria applied would depend on legal or administrative precedents, if not on the whims of authorities with discretionary powers.

There is some tendency in reporting on such marriages in English to call them "interracial" or "interethnic" -- but such qualifications are beyond the pale of Japanese law. There were, of course, "racioethnic" concerns on the parts of some lawmakers and administrators. And certainly the classifications of people on household registers were "racial" or "ethnic" in the minds of most people. Nonetheless, as far as household register laws and ordinances were concerned, such classifications were merely civil statuses, and did not themselves define private or social perceptions of an individual's "race" or "ethnicity".

International alliances

Hosokawa, in "Japanese Nationality in International Perspective" (1990), first states that "The old Nationality Law was declared applicable to Taiwan by Imperial Ordinance No. 202 of 1905" (Hosokawa 1990: 184). Later he states that "The old Nationality Law was declared applicable in Taiwan by Imperial Ordinance No. 289 of 1899" (Hosokawa 1990: 228).

Hosokawa's second statement is correct regarding the Nationality Law. The ordinance he refers to in his first statement concerned the 1898 revision of the 1873 proclamation permitting marriage and adoption alliances with aliens.

Imperial Ordinance No. 202 of 1905, promulgated in the Official Gazette (���� Kanpō) on 4 December 1905, was titled "Matter of enforcing in Taiwan Meiji 31 [1898] Law No. 21" (�����O�\��N�@�����\�ꍆ�����s�j�{�s�X���m��). The ordinance extended to Taiwan the short 1898 law which had modified rules and procedures concerning marriage and adoption alliances between Japanese and aliens, as provided for in Great Council of State Proclamation No. 103 of 1873 (Tashiro 1974: 849)

See 1873 intermarriage proclamation: Family law and "the standing of being Japanese" for the 1873 proclamation and its 1898 revision.

In other words, the same provisions that faciliated marriages between Japanese (including Taiwanese) and aliens in the Interior applied to Japanese (including Taiwanese) and aliens on Taiwan. Neither the 1873 GCS proclamation, nor the 1899 Nationality Law, in any manner referred to "race" or "ethnicity" in their facilitation of alliances between Japanese and aliens.

Interritorial alliances

Today, articles and books on "interracial" this and "interethnic" have become extremely fashionable that is academia. In the past, too, alliances between people of different nationalities -- Japanese-German, Japanese-Chinese -- were typically viewed as "interracial", whether or not countries of the two parties racialized their own national affiliations, or the national affiliations of other countries.

Contemporary writing about Taiwan, in English, was no exception. The following remarks about "Inter-racial Marriages" appear under "The Civil Code" in "The Law" chapter of a book called Taiwan: A Unique Colonial Record, 1937-38 Edition) (page 76-77, underscoring mine).

|

(2) The Civil Code

2. Orders and Ordinances about Inter-racial Marriages between the Taiwanese and Natives of Japan Proper: The question of inter-racial marriages between the Taiwanese and the people from Japan Proper was long a mooted point. The Imperial Ordinance No. 361 (1932), the Order of the Governor-General of Taiwan, Ritsurei, No. 2 (1932) and the Ordinances No. 7 and 8 of the Government-General (1933), opened the way to inter-marriages between the old and new subjects of the Japanese Empire. As a matter of fact, marriages between Taiwanese and the people from Japan Proper had often taken place previously in various parts of the Island. The Ordinances and the Order of the Governor-General stated above, justified such marriages from a legal point of view, producing a far reaching effect in cementing the kinship between the "two members of the family." In this connection, it may be mentioned here that the proclamation of the Ordinances and the Order of the Governor-General, mentioned above marked a considerable progress taken towards the adjustment of the census registration of the Taiwanese. |